House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W., & Gupta, V. (eds.). (2004). Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. 818 pages.

As the title of Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies (hereafter also referred to as CL and O or GLOBE), suggests, culture takes the place of primacy in this academic work on leadership.

GLOBE is an acronym for the ‘Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour Effectiveness’ research program. The program consists of three phases, and phases 1 and 2 are reported in CL and O. CL and O examines culture as it relates to leadership in all the major regions of the world, with the added twist that the data came from organizational middle managers in three targeted industries: food processing, financial services, and telecommunication services. These industries were determined to be present in all countries of the world but to be systematically different from one another. These differences have important implications for organizational culture. For example, whereas the food-processing industry is relatively stable, the telecommunications and financial industries may be stable or unstable, depending on country and economic conditions.

CL and O is more than a summary, of data gathered from around the world. CL and O is also a statement: a foundational shift in leadership thinking from individual leadership theory (ILT) to cultural leadership theory (CLT). As such, it is a landmark work.

Enormity of Work

CL and O is staggering. On face value the information that is presented in the work is overwhelming. The GLOBE study describes how each of 62 societies in 10 regions of the world scores on 9 major dimensions of culture and 6 major behaviors of global leaders. By my count, the book contains 269 tables and 67 figures to accompany the 760 pages of text.

But not to worry. For if you persist, you will be rewarded with a dazzling array of profound insights, and you will come away feeling as if you can pound your chest with fistfuls of cross-cultural management muscle. When you acquaint yourself with CL and O’s basics, you can have a field day by exploring questions of interest. What would you like to know or compare in the interface of culture, leadership, and organization? Think it—and you probably not only can read about it, but most likely you also can see it charted for you. The encyclopedic findings are fascinating in their own right, but what is even more important is that they yield wave upon wave of consilient reading.

Think of GLOBE as a meal—an 808 page full course dinner (including the 48 pages of index), a work cooked over a decade (1993-2003), testing 27 hypotheses that linked culture to outcomes. It has been served to your table by 170 interviewers, from a questionnaire of 735 items, that queried 17,300 middle managers of 3 target industries, divided into 10 regions, and scattered among 62 countries throughout the world. So relax and enjoy the meal. The chefs are professors: Robert House, Paul Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta (respectively from University of Pennsylvania, University of Maryland, University of Calgary, New México State University, and Grand Valley State University). The cuisine is research: a filling foray into global leadership.

This is leadership as you have never tasted before—leadership simmered in a 62-flavor culture sauce and topped off with organizational dessert from three industries of very contrasting flavours (finance, food process, and telecommunications).

Variations on Leadership Perspectives

Leaders have existed in all cultures throughout human history. One can glean the practice and philosophy of leaders and leadership from many ancient sources. Symbols for leader have been found in Egyptian hieroglyphics, in the Hebrew scriptures, in Confucius’s writings in China, in Greek classics such as Homer’s Iliad, in the Gospel accounts of Jesus, in the letters of the Apostle Paul, and more recently, in Machiavelli’s rules of power realism from the 16th century. Yet, curiously, the word leadership is a relatively new addition to the English vocabulary, appearing only 200 years ago in writings about political influence in the British Parliament.

Recently, from Stogdill (1974) to Yukl (2002), most definitions of leadership seem to have concepts of influence and the setting of goals at their core. In other words, leaders influence others to help to accomplish group or organizational objectives. Recall, for a moment, some of the concepts that a search for cross-cultural effective leadership reveals:

Effective leadership styles of participation common in the individualist West are questionable in the collectivist East. Asian managers heavily emphasize paternalistic leadership and group maintenance activities.

Charismatic leaders are recognizable but may demonstrate be highly assertive (John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr.) or quietly non-assertive (Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela and Mother Teresa).

A leader who “listens carefully to what you say” is valued in the U.S but not China; aleader who “praises you to others, but not you directly,” is China but not in the U.S.

Participatory leadership is valued in Western leadership zones, but in Arabian countries the most prized leadership style is the combination of family and tribal norms and bureaucratic organizational structures that foster authoritarian management practices.

These examples all speak to the issue that CL and O brings front and center: To what extent is leadership culturally contingent? House et al. address academically what expatriate managers in multinational companies have never been able to avoid practically, the imprint of culture on daily operations. To do this, CL and O acknowledges and builds on the literature of the past twenty-five years.

Although there are, in fact, widely accepted cultural leadership essentials that managers have found useful for decades, two are especially noteworthy. The first is the inescapable essential (Hofstede, 1980; Laurent, 1983; Trompenaars, 1993; Davis and Bryant, 2003) that acceptable management practices found in one country are hardly guaranteed to work in a different country, even in a neighboring country (as in the near-neighbors of Europe). The second is that there is also agreement that commonalities (cultural universals) as well as differences (cultural specifics) across cultures.

Whereas defining leadership creates an academic buzz, the labor of defining leadership across cultures presents a particularly horrific nest of stinging difficulties. Indeed, capturing the essence of effective leadership has been an elusive goal throughout history. CL and O, therefore, is invigorating on two counts. First, the GLOBE study goes a long way toward confirming the contention that universal and globally appreciated leader attributes exist. Second, CL and O sets the mark by demonstrating that the importance and value of leadership vary across cultures and leadership and that, therefore, they are culturally contingent.

When GLOBE began in 1993, researchers considered cross-cultural theory inadequate to clarify and expand upon the diverse cultural universals and cultural specifics that had been elucidated in cross-cultural research. To address those theoretical inadequacies, the GLOBE study (1993-2003) tested this fundamental assumption: that the basic functions of leadership have universal importance and applicability, but also that the specific ways in which leadership functions are enacted are strongly affected by cultural variation.

From region after region, the data poured in. Americans, for example, tend to be enamored of the notion of leadership, placing a premium on leaders. For most Americans, the term leadership evokes a positive values response—leadership is a desirable characteristic and highly praised. Americans, Arabs, Asians, British, Eastern Europeans, French, Germans, Latin Americans, and Russians tend to romanticize the concept of leadership and consider leadership in both political and organizational arenas to be important. Leaders in these cultures are commemorated with statues, names of major avenues or boulevards, or names of buildings.

But such commemorations are absent in Australia, Canada, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the German regions of Switzerland. Some studies show that practically, when Europeans say “leader,” the conditioned reflex is “Hitler.” Even the French call leadership an unintended and undesirable consequence of democracy, a “perverse effect,” as they say. Many people of German-speaking Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia are skeptical about leaders and the concept of leadership for fear leaders will accumulate and abuse power. In Holland, consensus and egalitarian values are highly esteemed. Other nations downplay the importance of leadership. Japan’s CEOs of successful corporations credit subordinates for organizational accomplishments while de-emphasizing their own role as contributors to organizational success. And although Anglo societies are known for their visionary leadership that emphasizes team-building and allows for individual autonomy, the commonly effective form of leadership in Middle Eastern societies (Jordan and Saudi Arabia) is the caliphal model, which is based on authoritarian leadership and disallows dissent by team members.

Beyond definitions of leadership, consider leadership behavior patterns. Modal leader behavior patterns differ widely across countries in their emphasis on individualist versus team orientation, particularism versus universalism; performance versus maintenance orientation; authoritarian versus democratic orientation. Additionally, there are paternalism; reliance on personal abilities, subordinates, or rules; leader influence processes; and consensual decision-making and service orientation.

Across a mix of cultures, the emphasis is on the importance of strong family ties and paternalistic management practices. Also, these businesses retain their characteristics even after expansion into larger organizational entities. Samsung and Hyundai Motor Company, Korean chaebols, also fit this model of family-centered conglomerates in which leadership succession is family dominated.

Is it healthy to fill a company with family and relatives? The normal answer in America would be no. But organizational management practices in China, India, and Hong Kong are strongly based on kinship relationships; that is, hiring relatives is often the norm rather than the exception. And the relative-hire practice is a system used in many large-scale enterprises in these countries as well. Large Indian firms currently practice many of these behaviors, such as obedience to elders based on deference to the wisdom of experience. Five of the largest business organizations in India— Reliance, Birla, Goenka, Kirloskar, and Tata—remain family-managed. In Mexico grupos, or groups, are the large family owned and operated business structures.

The GLOBE leadership survey included the following variables within a cross-cultural leadership framework: the origin of leaders, modernization, the unique role-demands of leaders, antecedents to preferred leader behavior, leader prototypes, preferences for leadership styles, leadership behavior patterns, and the behavioral impact of leadership.

GLOBE Basics

House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta, however, do not just assume theory. They acknowledge, affirm, and set out to create new theory. They start Part I of the five sections of this tome with a chapter of illustrative examples of GLOBE findings (pp. 1–8) followed by an overview chapter by House and Javidan on their guiding theory (pp. 9–48). Simply put, the theory that guides the GLOBE research is an integration of three schools of leadership theory:

- Implicit leadership theory (Lord & Maher 1991) and value-belief theory of culture (Hofsted 1980; Triandis 1995).

- Implicit motivation theory (McClelland 1985).

- Structural contingency theory of organizational form and effective- ness (Donaldson 1993); Hickson, Hinings, McMillan, & Schwitter 1974). (pp. 9–28)

In brief, I agree with their contention that what they do with cultural leadership and organizations has never been done before.

Most of the leadership research during the past half-century has been conducted in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe (Yukl, 2002). Prevailing North American theories have been individualistic and rationalistic. They have stressed individual incentives and follower responsibilities, and they have assumed hedonistic motivation, the centrality of work and democratic orientation. Other regions interested in research investigate more the collectivist and religious. They have stressed group incentives and follower rights, and they have assumed altruistic motivation and the centrality of family in a hierarchal setting. If it is true that more than 90 percent of the organizational-behavior literature reflects U.S.-based research and theory, surely GLOBE will stand as a major beachhead in the global liberation of leaders and organizations from that hegemony.

This 1993-2003 worldwide survey dips back into anthropologist Robert Redfield’s definition of culture: Culture is the “shared understandings made manifest in act and artifact.” From that point of departure, the GLOBE research project examines culture as practices and values. Practices are acts or “the way things are done in this culture,” and values are the judgments about “the way things should be done,” the artifacts of human spiritual, moral and mental construct. Specifically, GLOBE is about CLTs—“culturally endorsed implicit theories of leadership”—a rather awkward match between acronym and designation. Be that as it may, CLT is the acronym of choice used throughout the book.

GLOBE is intended to be rigorous. Its stated audience is the academic community, yet it carries a yearning to feed the hungry strugglers in the global management jungle. GLOBE is not an easy read, but it is not an impossible read. As I have said, if you persist, you definitely will find it to be a most profitable read.

With that in mind, I will track with House and Javidan for a moment, because their data-reporting is unabashedly theory-woven and theory-laden. The conceptualization bottom line? What previous studies of the past 60 years of U.S. leadership put forward was “aggregated to the societal level of analysis” in GLOBE (p. 16). Thus, the “central proposition” of GLOBE’s integrated theory is that “the attributes and entities that differentiate a specified culture are predictive of organizational practices and leader attributes and behaviors that are most frequently enacted and most effective in that culture” (p. 17). The shift in the GLOBE study, then, is from individual motivations to cultural forces as the major determinants of leaders and of the framing of leadership.

Implicit Leadership Theory

According to the implicit leadership theory of Lord and Maher, individuals have implicit beliefs, convictions, and assumptions concerning attributes and behaviors that distinguish leaders in three ways: leaders from followers, effective leaders from ineffective leaders, and moral leaders from evil leaders. These sets of beliefs, convictions and assumptions held by individuals are referred to as individual implicit theories of leadership.

Building on these theories, a “major part of the GLOBE research program is designed to capture” the culturally endorsed implicit theories of leadership—“the CLTs of each society studied.” According to House and Javidan, they found that “if aggregated to the societal level of analysis, responses to the leadership questionnaire reflect the culturally endorsed [italics added] implicit theory of leadership of the societies studied.” Thus, they report finding a . . . “high and significant within-society agreement with respect to questions concerning the effectiveness of leader attributes and behaviour. Further, aggregated leadership scores were significantly different among the societies studied. Thus, each society studied was found to have a unique profile with respect to the culturally endorsed [not individually endorsed] implicit theory of leadership.” (pp. 16–17)

Value-Belief Theory

The same holds true for the theoretical foundations in value-belief theory. According to Hofstede’s and Triandis’s value-belief theories, the values and beliefs held by members of cultures influence not only the degree to which behaviors are enacted, but also the degree to which they are viewed as legitimate, acceptable, and effective. And this reality applies to the behavior of groups and institutions within cultures as well as to individuals. The GLOBE theoretical base is a theory of cultural forces, whereas the preceding cultural work of Hofstede, Triandis, and McClelland are all value- belief theories that focus on individual motivations as primary. House and Javidan are clear here also: “Whereas McClelland’s theory is an individual theory of both non conscicous and conscious motivation, the GLOBE theory is a theory of motivation resulting from cultural forces.” (17) Thus, the central proposition of the GLOBE CLT—culturally endorsed implicit theory of leadership—is that “the attributes and entities that differentiate a specified culture are predictive of organizational practices and leader attributes and behaviours that are most frequently enacted and most effective in that culture” (p. 17)

From an academic standpoint, which is the orientation of the authors of CL and O, what has been assembled by the GLOBE study is put forward as “a very adequate data-set to replicate Hofstede’s (1980) landmark study and extend that study to test hypotheses relevant to relationships among societal-level variables, organizational practices, and leader attributes and behavior” with “sufficient data to replicate middle-management perceptions and unobtrusive measures” (p. xxv.). As I mentioned earlier, in order to accomplish that, University of Pennsylvania’s Robert House led a team that eventually included 170 other social scientists and management scholars called CCIs, or country co-investigators. The CCIs interviewed some 17,300 managers from 951 organizations in 62 societies, representing all the major regions of the world—10 clusters of countries by their count: Latin America, Anglo, Latin Europe, Nordic Europe, Germanic Europe, Eastern Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East, Confucian Asia, and Southern Asia.

You can readily see their approximation to Samuel Huntington’s 1996 typology in The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. Huntington identified eight worldview-related or religion-based civilizations: Western, Latin American, Islamic, African, Sinic, Hindu, Orthodox, and Japanese. (And perhaps only seven, with African being only a “possibly” according to Huntington; but not nine, as mistakenly listed by Triandis in the Forward (p. xviii.), who includes Buddhist, which Huntington, for his reasons, excludes.)

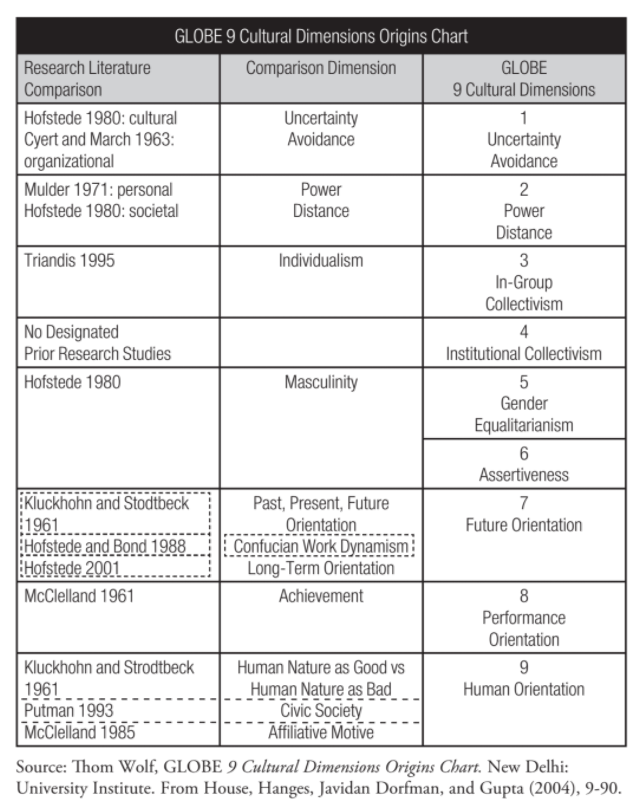

Previous research such as Hofstede’s monumental 1980 study identi- fied four dimensions of cultural variation: power distance, individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance. GLOBE expands these to nine dimensions: future orientation, gender equality, assertiveness, humane orientation, in-group collectivism, institutional collectivism, performance orientation, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance.

In 1994, Schwartz, following Kluckhohn (1951) and Rokeach (1973), extended his individual-level taxonomy of human values to the society lever to identify dimensions that differentiate cultures. His seven ecological dimensions are Embeddedness (previously labelled Conservatisim), Intellectual Autonomy, Affective Autonomy, Hierarch, Egalitarianism, Mastery, and Harmony (Swartz 1994, 2001; Schwartz & Melech 2000).

The relationships to these and other studies are discussed in Chapter 5 (pp. 122–150), but the final result is that in a way unexplored to now, the GLOBE culture and leadership scales set new benchmarks in the field of study. Here is a brief description of the nine cultural dimensions investigated by GLOBE:

Future orientation is the degree to which individuals in organizations or societies engage in such behaviour as planning, investing in the future, and delaying individual or collective gratification. In countries high on this attribute, people do not visit spontaneously, but call before visiting. Those of future orientation enjoy economic prosperity, and they experience scietific advancement, democracy, gender equality, and social health.

Gender egalitarianism is the degree to which an organization or a society minimizes gender role-differences while promoting gender equality.

Assertiveness is the degree to which individual in organizations or societies are assertive, confrontational, and aggressive in social relationships.

Humane orientation is the degree to which individuals in organizations or societies encourage and reward individuals for being fair, altruistic, friendly, generous, caring, and kind to others.

In-group collectivism is the degree to which individuals express pride, loyalty, and cohesiveness in their organizations or families.

Institutional collectivism is the degree to which organizational and societal institutional practices encourage and reward collective distribution of resources and collective action.

Performance orientation is the degree to which an organization or society encourages and rewards group members for performance improvement and excellence.

Power distance is the degree to which members of an organization or society expect and agree that power should be stratified and concentrated at higher levels of an organization or government.

Uncertainty avoidance is the extent to which members of an organization or society strive to avoid uncertainty by relying on established social norms, rituals, and bureaucratic practices.

The following chart, a family tree of GLOBE’s nine core cultural dimensions, gives some idea of the wide-range antecedents fused into the new GLOBE identity.

GLOBE explored two forms of a question for each dimension. The first form measured managerial reports of practices (what is) and values (what should be) in their organizations. The second form measured practices and values in their societies. Thus, in this aspect alone there were 18 scales to measure practices and values with respect to the core GLOBE dimensions of culture.

Leadership

GLOBE researched a set of CLT leadership profiles developed for specific cultures and clusters of cultures. Essentially, CL and O establishes how the 6 following CLT leadership dimensions vary as a function of the 9 CLT cultural dimensions among the 10 regional culture clusters. The 6 global leadership dimensions are labeled as charismatic/value-based, team oriented, participative, humane oriented, autonomous, and self-protective. These 6 global CLT leadership dimensions are statistically grouped into 21 primary or first-order leadership dimensions. As Dorfman, Hanges, and Brodbeck explain, “They can be thought of as being somewhat similar to what laypersons refer to as leadership styles” (p. 675) and are defined as follows:

Charismatic/value-based (C/V-B). The ability to inspire, motivate, and expect high-performance outcomes from others on the basis of firmly held core values. The C/V-B dimension includes six subscales: visionary, inspirational, self-sacrifice, integrity, decisive, and performance oriented.

Team oriented (TO). TO emphasises effective team building and implementation of a common purpose or goal among team members. Collaborative team orientation, team integrator, diplomatic, malevolent (reverse scored), and administratively competent are the five subscales.

Participative (P). The two subscales, autocratic and non-participative, are both reverse-scored in this dimension and reflect the degree to which managers involve others in making and implementing decisions.

Humane oriented (HO). Supportive and considerate, including the qualities of compassion and generosity, leaders are recognized around the world. The GLOBE CLT humane oriented leadership dimension includes modesty and humane oriented as two primary subscales.

Autonomous (A). This is a leadership dimension that has not previously appeared in the literature. This newly defined dimension refers to independent and individualist leadership (with a subscale also curiously labeled autonomous).

Self-protective (SP). This sixth and last global leadership dimension is also a newly defined attribute. It focuses on ensuring the safety and security of the individual or group member—looking out for yourself. Included in the research are five subscales: self-centered, status conscious, conflict inducer, face saver, and procedural.

What I found utterly captivating is that in light of the fact that CLT hypothesizes that culture will have a pervasive influence on values, expectations, and behavior and would, therefore, influence the content of the CLT profiles (which the research bore out), what might be most remarkable of all the GLOBE findings is that there is a universal agreement (not just a cultural consensus) on what constitutes effective leadership. That is not to say that there are not cultural or cluster differences. But it is to say that around the world peoples of all the regions and among all the cultures have identified something supremely human, something recognizable, something moral, something admirable about a true leader.

GLOBE, in identifying culturally endorsed leadership profiles for effective leadership, appears to have accumulated from around the world a first-ever profile of a leader on Planet Earth. Globally, the six global CLT leadership dimensions received three reports.

Charismatic/ value-based, team-oriented, and participative leadership are generally reported to contribute to outstanding leadership.

Also reported (neutral in some societies and moderate in other societies) is that humane oriented leadership contributes to outstanding leadership.

Autonomous and self protective tend to be negatively reported globally: Autonomous leadership ranges from impending to slightly facilitating outstanding leadership, and self protective leadership, around the world, is generally reported to impede outstanding leadership.

If the GLOBE research project from the 10 culture clusters around the world gives us a report that is accurate, representative, or both from the 17,300 individuals interviewed, then we now have a new and major contribution to what I call the global conversation, the worldwide discussion of this global era: How do we best live life on this planet?

If you pause to think about it, what GLOBE has done is somewhat sobering, perhaps even inspiring in its own way. Entering the 21st century, the GLOBE study alerts us to the fact that from the hearts and minds of our neighbors around the world, we are in rather remarkable agreement on the kind of leader we admire, aspire to be, and would prefer for teamwork. The model global leader is a leader who is charismatic/value-based, a team-oriented and participative person, mobilizing us to principled and collaborative action—and if possible, one who is also humanely oriented, that is, a person who is supportive and generous, perhaps even modest.

But we also know something else. From the global-conversation perspective—How do we best live life on this planet?—the GLOBE Research Program gives a rather certain negative conclusion. We are also hearing that there is something in the human heart, something in the human psyche that recoils from that person in a place of leadership— that person over others—who seems only or especially to somehow be primarily or significantly looking out for self.

The GLOBE results, then, are unique in their broad geographical coverage. They support the CLT thesis that the societal system and the cultural worldview have the most significant and strongest effects on all the organizational culture dimensions measured. Influences from industry mildly impact some of the measured aspects of organizational cultures across all societies.

Among the 10 culture clusters, the CLT profiles vary as a function of the 9 cultural dimensions and the dominant societal system of the various culture clusters. The report from the 10 cultural regions in briefest summary:

The Latin America Cluster leader (of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, and Venezuela) practices C/V-B and TO leadership and is not adverse to some elements of SP. Although independent action is not endorsed, P and HO behaviors are seen favorably, but not as highly as in other clusters.

Somewhat similarly, a leader from France, Israel, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and French-speaking Switzerland of the Latin Europe Cluster endorses C/V- B and TO leadership. An action is not endorsed and HO behaviors do not play a particularly important role. And, although P leadership is viewed favorably, “the Latin Europe cluster would not be noted for it.” In other words, high scores on “should be,” low scores on “as is.”

The Anglo Cluster includes Australia, English-speaking Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, White sample South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The reported outstanding leader includes high C/V-B elements with high levels of P leadership carried out in a HO manner. TO is valued, but not ranked among the highest global CLT dimension. SP is viewed negatively.

Germanic Europe Cluster (Austria, former GDR-East Germany, former FRG-West Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland) seeks out C/V-

B leaders who believe in P leadership but who also support independent thinking while rejecting elements of SP.

In the Nordic Europe Cluster (Denmark, Finland, and Sweden) the effective leader is seen as the person whose style includes C/V-B and TO leadership. However, in contrast to most other cluster profiles around the world, the Nordic cluster is particularly noted for high P leadership and low HO and SP attributes.

A leader exemplar for the Eastern Europe Cluster (Albania, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Poland, Russia, and Slovenia) would be one who is somewhat C/V-B, TO, and HO, but is his or her own person, does not particularly believe in the effectiveness of P leadership, and is not reluctant to engage in SP behaviors if necessary.

The Confucian Asia Cluster includes China, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. An example of effective leadership for this cluster includes C/V-B, and perhaps TO, leadership. SP actions are viewed less negatively than in other cultures, especially when coupled with motivations arising out of group protection and face saving. The Confucian Asia cluster is among the highest scores in the world, along with South Asia and the Middle, in SP. P leadership is not expected.

South Asia Cluster. India, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand form the cultures of this cluster. GLOBE identifies an effective leader in South Asia as a person who exhibits C/V-B, TO, and HO leadership attributes. That same leader is relatively high on SP behaviours and is not noted for high levels of P leadership. Having lived in Southeast Asia (Thailand), and now living in India, I have not found at all convincing the GLOBE arguments that link India and Iran to the Southeast nations of Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. The GLOBE charts do, however, allow for breakout comparisons.

The Sub-Saharan Africa Cluster is composed of Namibia, Nigeria, Black sample South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The Sub-Saharan region has the highest global score for the HO CLT leadership dimension. An effective leader exhibits C/V-B, TO, P, and HO leadership, and is noted for relatively high endorsement of HO characteristics. A and SP characteristics, in the Sub-Saharan context, only slightly impede effective leadership.

The GLOBE summary of the Middle East Cluster (Morocco, Egypt, Turkey, Kuwait, and Qatar) immediately catches your attention, for it begins with a contrast: “There are a number of striking differences in comparison to other clusters.” For one, the leadership dimensions contributing to outstanding leadership in this cluster—C/V-B, and TO—have the lowest scores and ranks relative to those for all other clusters. Second, P is viewed positively, but again scores low compared to other cluster’s absolute scores and ranks. Also, SP has a special place. SP “is viewed as an almost neutral factor, however, it has the second-highest score and rank of all clusters.” Thus, when comparing these relative CLT leadership scores with other clusters’ scores, “almost all Middle East CLT scores rank at the low end of the leadership comparisons.” Several explanations are tendered, but the GLOBE conclusion is that “it is likely that the pervasive influence of the Islamic religion is a key to understanding the Arab world, and presumably in the Arab world” (pp. 694-697). Even with the lower CLT scores, the universal ideas about and aspirations for an effective leader come through. Respondents in the Middle East look to a person who exhibits C/V-B and TO leadership, as well as P and HO leadership, “but not nearly to the extent indicated for other clusters.”

So, while the full extent of culture’s influence is still unknown and although the way leadership is culturally contingent remains relatively unmapped, “given the current trend toward globalization of economies and an ever increasing number of multinational firms,” the Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour Effectiveness research program certainly sheds some light on marketplace-behavior effectiveness in our global multicultural world.

In the afterglow of C, L, and O, three thoughts hover in my head. First, Culture, Leadership, and Organizations obligates us. I chuckled at the first sentence of the Preface: “The idea for GLOBE came to me in the summer of 1991.” Does this mean that, in time, we are going to look back to House’s summer inspiration as a Kuhnian moment, a time of new integration in a section of the social sciences, a veritable paradigm shift? Perhaps. It seems as though the research team might think so. At any rate, C, L, and O is a serious and wide-ranging work and we are all in its debt.

Guided by the Culturally Endorsed Implicit Leadership Theory (CLT), GLOBE lays out a ten-year project based on an integrated, cross-level theory of the relationship between cultural values and practices, leadership, and organizational and societal effectiveness. As one who has tracked the field of cross-cultural leadership for over a third of a century, I find myself in relieved agreement and with an invigorated interest in their new level of theorizing. A new level of integration and documentation has been achieved with the convergence of the CLT (which expanded implicit leadership theory to the cultural level) the strategic contingency theory, McClelland’s achievement theory of human motivation, and Hofstede’s culture theory.

Overall, GLOBE extends the current knowledge-base by a more comprehensive conceptualization of cultural dimensions, even introducing new dimensions. The conceptualization and measurement of culture in Redfieldian terms of practices and values will no doubt prove to be a rich vein for further research. At the organizational level, of course, there are the nine new dimensions of organizational culture. For all that, we are all indebted to GLOBE.

Second, GLOBE nudges us. The luster of some things diminish with exposure. Others increase. C, L and O surprises anyone on first contact. But C, L and O moves beyond the novel. It has a certain ascending quality: The more exposure you have to it, the more it amazes you. For me, it has manifested a kind of consilient quality—that happy mind-pleaser of jumping together, those points of insight where knowledge from one discipline bounds over the fences of specialization and jumps the disciplinary gaps to merge into a kind of greater, higher, deeper, richer—and yes more practical—dimension of comprehension. So I encourage you to master the basics of the C, L, and O configuration. For in the midst of the 818 total pages of those some 269 Tables and 67 Figures summarizing the 17,300 interviews about 735 items that tested 27 hypotheses linking culture to outcomes from 62 countries in 10 regions, I think you might repeatedly find yourself if not astonished, at least nudged a little further into understanding the global work-a-day world.

Third, Culture, Leadership and Organizations insinuates us: In the older sense (sinus curve, to bend) of gradually or in a subtle, indirect, or artful way; not in the more recent sense of implying in a deviously subtle way. C, L, and O insinuates us into the future; it artfully, indirectly, but in a winning, favorable, and even almost imperceptible way, introduces us to issues that will only become more obvious in the first half of the 21st century.

I predict that the GLOBE research program bodes well to be fruitful for the future. In the Foreword, Harry C. Triandis says, “Thousands of doctoral dissertations in the future will start with these findings.” Triandis is, no doubt, spot-on. Certainly that is part of the intent of the authors of C, L, and O: “The wealth of findings provided in this book sets the stage for a more sophisticated and complex set of questions” and “we intend to speed up this process by posing a series of questions to help direct and energize further research on important issues in cross-cultural management.” (p. 727)

For example, the GLOBE research clearly indicates that integrity is a leadership universal. But what does integrity mean for a Chinese, an Indian, an American, or an Arab? How do people in different cultures “conceptualise, perceive, and exhibit behavior that reflects integrity?” Or consider in what ways other than visible behavior “do leaders connect to others in their organizations? And to what extent are these nuances, nonverbal behaviours, and emotional expressions universal or culturally contingent?”

Negatively, think of the violation of societal cultural norms. Culturally implicit leadership theories are shaped by societal and organizational cul- tures. Leaders grow up in their cultures “and build their worldview on the basis of their own learning and development.” In the workplace, they have to motivate and energize employees who are also culturally conditioned.

What if leaders violate societal cultural norms? Can they violate the norms and succeed? And, under what conditions might they violate these norms? Which norms are more critical for leaders—the societal norms or those held to be more universal? For although some people might think these only “academic questions, they do have significant managerial implications.”

Above the host of emerging questions, one intrigues me most. Perhaps it may be most vital for the social benefit and cultural flourishing of all the 10 regions of the world. It is the question-set treated in just five paragraphs in the last chapter: that the commonality of charismatic leadership across cultures may be due to its moral and ethical foundations. GLOBE’s conclusions and future directions draw brief attention to this. It should not be missed or ignored, Some individuals have suggested technological reasons for the commonality of charismatic leadership across cultures. But more have suggested that “leadership may satisfy universal and basic human needs . . . that go beyond cultural boundaries.” And, another “possible driver of universality may lie in ethical values.” Transformational leadership, especially, it has been suggested, may be “rooted in strong ethical values.” This is the kind of thinking anticipated in the Judeo-Christian worldview under the categories of the universal human characteristic of the imago dei (the image of God) and human conscience, along with the indicator lists of trans-culturally approved moral virtues and vices given by the apostle Paul in his universal pattern of discipleship for personal and cultural transformation.

Furthermore, “if it is true that universal needs drive universal leadership attributes, then a related question concerns the interaction between universal and cultural drivers of leadership. How do they interact? Which one is more important? Under what conditions?” It is at this juncture that some of the most fruitful and socially beneficial research will no doubt find its departure.

At the end of the 20th century, Huntington shocked many people with his bold assertion that every major civilization is grounded in a major world religion. It should not have. For toward the beginning of the 20th century, one of the founders of modern social science, Max Weber, had already intimated the same point. In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, that student of ancient history turned sociologist of Heidelberg University, drew unflinching attention to the vital connection between worldview and world venue. Considered somewhat commonplace in sociology and cultural anthropology, some have found this new, even revelatory. From the perspective of GLOBE, it is simply something that has been documented.

But still others have commented on the same. Just recently, for example, Dipankar Gupta, a secular Hindu scholar made the same point. Gupta is professor of sociology, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University. He has also taught economics at Delhi University. In Ethics Incorporated: Top Priority and Bottom Line (2004) Gupta, in comparing the Buddhist and Judeo-Christian worldviews, notes that it is “the general conclusion among social historians that of all religious persuasions, Christianity is the most conductive to modern corporate enterprise.”

The point here is not to deny or defend Gupta’s position. The point here is to firmly note that leaders of business and organizations around the world will profit enormously from future research that investigates the relationships between religion and leadership and societal values and practices as admired and acted on in the marketplaces of the world. Surely one of the richest and most socially beneficial areas for future research will be the paths taken from this oasis of foundational data in GLOBE.

If you are one of those leaders addressed by GLOBE—leaders “trying to improve their societies’ well being”—then I recommend Culture, Leadership, and Organizations. Do not let it intimidate or overwhelm you. Stay with it. Master it’s basics. Before long you will find yourself indebted for a host of insights, repeatedly nudged headlong into delightfully unexpected consilient moments, and bent ever so artfully toward the deeper questions, even the basic question, of our shared future: What is the best way to live life in the marketplace of daily life?

Dr. Thom Wolf is Director of University Institute in New Delhi, India. University Institute is an Asia-based learning group with clients in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.