A DEPRESSING VACATION IN PARIS!

From the moment I stepped off the plane in Paris, I was depressed. Imagine! In Paris—art, food, history, beautiful sights! My dream of visiting this great city had come true, but an old enemy, dark depression, settled in. As the days went by, I half-heartedly toured France in this, my first vacation in several years. I reflected on the state of my heart—why was I sad when most everything in my life was going so well? A new InterVarsity ministry pioneered on the campus of Northern Arizona University, many students meeting Jesus for the first time or deepening their already existing relationships, missions projects encouraging them to have a heart for the world, small group Bible studies helping students encounter the living God, broken lives being restored—all of these things pointed toward fruit and God’s obvious blessing of the ministry, yet I felt flat and unsatisfied. I soon realized that I felt this way because I was away from ministry. The ups and downs, highs and lows of ministry successes and failures had determined my identity for the past two and a half intense years. Now, being away from campus, I did not know who I was. The more startling revelation came at the end of my vacation. While I was praying, the Spirit spoke and forever changed the course of my life.

I became convicted that I had used people’s lives to get my own needs met and fulfill my own dreams for building a successful ministry. In my system of use, students became objects to fulfill my dream of pioneering a student fellowship. Upon meeting them, I quickly calculated in my mind where they might fit into the plan and how they could “serve” the fellowship. Rather than having a posture that tried to determine how I might serve students, my posture focused on getting them to serve my vision. In this respect, I did not partner with Jesus.

I am thankful that God in his mercy revealed the true motivation of my pursuit of ministry early on and then gave me the grace to change by addressing the roots of my drivenness. He also transformed my posture toward ministry (and is still changing me) to be more like Jesus—serving rather than using. This transformation became the seedbed of a call to help people develop, grow, and mature to their full potential.

This is the story of my entrance into the developmental mindset. This mindset grew over the years and propelled me into pursuing research that could help me and others understand what it means to be developmentally minded and to create organizations that are characterized by development. Let me first, however, give some indications of how this idea continued to blossom as I worked with other leaders.

WORKING WITH OTHER LEADERS

I handed her a tissue so she could catch the tears streaming down her face. “I have given my best years to this organization,” she sobbed. “Sacrificed my health, carried out the tasks they required, and performed jobs that were difficult because I lacked the gifting. Now they want me to do something else ‘for the cause’ and I just don’t have the energy. I am tired; I haven’t followed my dreams—missions hasn’t been all what I thought it would be. Because I have been stuck doing administration, my passion for the lost is dying. I need to take action and ensure this won’t happen again, but how? Do I leave this organization? If so, where would I go?”

Repeated experiences of these scenes and other similar stories, as well as my own pilgrimage, infused my hope of doing research that could help organizations break their pattern of using people and embrace a more life-giving, developmental posture toward the people God entrusts to them.

GOD’S IMPERATIVE FOR DEVELOPMENT

In the last twenty years, my exposure to organizations through participating, teaching, and consulting reveals an intensifying concern for the people who work for the organizations. Anecdotally speaking, organizations often focus on people when trying to explore reasons for turnover or attrition. It is also a challenge presented by current generations (late Boomers, Generation X, and Generation Y) entering full-time ministry who call for a package of member care, mentoring and development; the appeal for the sacrifice for missions is no longer motivating (Walls 1996:260).

The Scriptures reveal that being a part of God’s mission and God’s Kingdom not only results in partnership in announcing the Kingdom but also in growth and development. Growth and development are God’s agenda for our lives. Consequently, it is an absolute imperative that the environments of our organizations and churches promote and enable developmental processes.

In my doctoral research, I endeavored to capture what makes organizations developmental and what organizations can do to be more developmental. This led to the creation of an integrated systems model that can be used for analysis and organizational change. For this study, I chose to focus on what would be considered an older mission organization—OMF International. Before further introducing OMF, I will define development.

DEVELOPMENT DEFINED

In the following paragraphs I explain my pilgrimage of arriving at a definition for development as it relates to people. It includes the final definition after data analysis.

The word “develop,” as defined in Webster’s dictionary, contains a number of images and definitions that illumine the concept of development.

Develop means to set forth or make clear by degrees or in detail; to expound; to make visible or manifest; to treat (as in dyeing) with an agent to cause the appearance of color; to subject (exposed photograph material) especially to chemicals in order to produce a visible image; to make visible by such a method; to elaborate by unfolding of a musical idea and by the working out of rhythmic and harmonic changes in the theme; to evolve the possibilities of; to make active; to promote the growth of; to move (a chess piece) from the original position to one providing more opportunity for effective use; to cause to unfold gradually; to expand by a process of growth; to cause to grow and differentiate along lines natural to its kind; to acquire gradually; to go through a process of natural growth, differentiation, or evolution by successive changes (a bud to blossom); to acquire secondary sex characteristics; evolve, differentiate, grow; to become gradually manifest; to become apparent; to develop one’s pieces in chess (1981:308).

The definition of develop provides rich metaphors to bring insight for our developmental process. First of all, to develop means “to set forth or make clear by degrees or in detail; to make visible or manifest.” This happens when chemicals are applied to photographic material so as to make an image appear. Develop also carries the idea of possibility or opportunity as when a chess piece is moved to another position, which enables further opportunity for effective use of other pieces. Develop connotes evolution of possibilities. Finally, to develop is synonymous with “to grow.” It is growth through successive changes, which eventually allow something/someone to become what it is meant to be—e.g., a plant produces a bud from which a blossom unfolds. The unfolding evidences a developmental process.

In this study whenever I use the word “development,” I am not referring to an organization’s goals and action plans for raising money—as is the case for organizations and churches that have a development department for raising funds. Nor am I referring to community development projects which organizations, churches, and communities undertake to decrease poverty and better society. Rather, when I use the word “development,” I refer to the process of transformation and growth that occurs in the lives of people—in relationship with God and their community—that allows them to embrace and participate in the mission of God—their destiny. “Each of us has a unique design—a destiny” (Miller and Mattson 1989:4). Growth and transformation occur as the “chemicals” of the Holy Spirit are applied to the human spirit. It is through God’s Spirit that persons continually evolve until who they have been created to be is more clearly manifested in their lives (Figure 1).

Extrapolating from the biblical accounts of what happens when God intervenes in human lives, I propose that development relates to personal transformation and destiny—specific calling in God’s mission—what some may describe as “becoming” through the process of being and doing. The process culminates in the ultimate transformation of becoming like Christ. On the other hand, God gives people the privilege of participating in his Kingdom work, his mission, and he has unique purposes for each of them. This is where destiny comes into the picture and correlates with an individual’s gifting and experiences.

Taking the above into account, development is defined as the individual and corporate processes God uses to (a) grow individuals into who they have been created to be and (b) lead and empower them to fulfill their unique destiny in the Kingdom while participating in the overall mission of the organization. Organizations that are developmental facilitate (by providing resources, assessment, support, training, etc.) the individual and corporate processes by which people grow into the persons God has created them to be and embrace their unique destiny in the Kingdom while participating in the overall mission of the organization.

OMF INTERNATIONAL

OMF International is a large mission organization that has been in existence since 1865.2 Founded by Hudson Taylor as China Inland Mission, OMF originated and characterized the modern faith mission by its interdenominational members, trusting the Lord for necessary support, focus on evangelism, headquarters on the field, and culturally adaptive measures (Bacon 1984:147,189). Through its various permutations of mission, structure, and geographical location, OMF has continued to innovate in order to be effective in its purpose of reaching East Asia’s people for Jesus Christ.

In recent years, OMF has grown to a missionary force of over 1,300 members (from Europe, North America, Africa, and Asia) with strong ministry efforts in thirteen countries (Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam) (Prescott 1997:5).

METHODOOGY

My study of OMF followed qualitative research methodology and incorporated a case study method including documents, in-depth interviews, focus groups, and events observation for data collection. Grounded theory methodology was used for data analysis with the aid of a qualitative research computer program.

I determined that this study required qualitative methodology for the following reasons. In the first place, the study centers on the experience of individuals in an organization. In this regard, it is a phenomenological study that focuses on people’s experience of development within OMF.3 People’s words and actions need to be studied in order to understand the meaning and process of development in the OMF context (Maykut 1994:46). Qualitative methods are particularly helpful for understanding and elucidating process (Patton 1990:95).

Second, the study of people’s development in OMF requires a sophisticated, varied technique due to the complexity of the issue. Development happens through people, events, circumstances, and experiences. This phenomenon cannot be studied with the controlled variables and environment of quantitative analysis with non-human instruments. Rather, it calls for a “human- as-instrument” method since that is the necessary instrument with enough flexibility to comprehend multifaceted complexity (Maykut 1994:26). Lincoln and Guba demonstrate human-as- instrument methods as most appropriate for complex “human” situations since they provide the possibility of capturing a complex, constantly changing situation (1985:193).4 As can be deduced, qualitative methods allow the researcher to approach their study in bricoleur 5 fashion, which in turn produces flexibility for dealing with complex phenomena. “Complexities cannot be understood by one-dimensional, reductionist approaches” (Maykut 1994:27).

Third, in order to understand the phenomena of development, research methods are needed that allow understanding from another’s point of view, namely, from the perspective of members of OMF. This requires relationship building and a posture of “indwelling” and interaction with the participants of the study (Maykut 1994:39). Gathering information about people, which will ultimately emerge into theory, necessitates the researcher’s involvement with the people (Rubin and Smith 1995:12). In other words, an environment of presence is needed where people feel comfortable to talk about their lives, their joys, and their struggles. Meaning develops through relationship (Maykut 1994:39).

Fourth, the study is designed to describe human experience, not to test an already existing theory (Rudestam and Newton 1992:37). Through the discovery of people’s experience of development, a theory emerged, which is the exact intention of qualitative research methods.

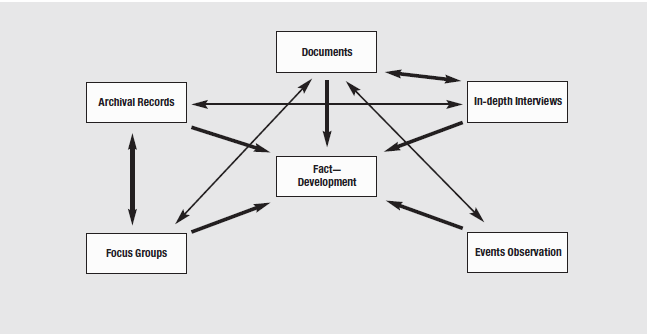

Researchers capture words and actions through participant observation,6 in-depth interviews, group interviews (focus groups), and the collection of relevant documents (Maykut 1994:46). This study’s research design involved a case study of OMF using interviews, focus groups, events observation, archival records, and documents. (See Figure 2.)

CASE STUDY

Yin proposes the criteria for choosing case studies as a strategy for when “how” and “why” questions are being asked, when the researcher has little control over events, and when the researcher is trying to obtain data from real-life situations (Yin 1994:1). Examples of these situations would include various social science, planning, psychology, organizational, and management studies. The purposes of research in case studies converge in asking how phenomena have been experi- enced and why phenomena have occurred with contemporary events in which behavior cannot be manipulated (Yin 1994:8). Therefore, Yin provides the following definition:

[A case study is] an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident. . . . Case study inquiry copes with a technically distinctive situation in which there will be many more variables of interest than data points, and as one result relies on multiple sources of evidence, with data needing to converge in a triangulating fashion, and as another result benefits from the prior development of theoretical propositions to guide data collection and analysis (13).7

The OMF study matches all of the “how,” “why,” contemporary event, and non-manipulative criteria. The case study method is also the appropriate method for studying implementation of programs and organizational change (22).

As conveyed earlier, this study seeks to understand people’s experience of development within the context of an organization—OMF.8 In order to effect organizational change, OMF intentionally introduced a comprehensive program of development for their members in the mid 1990s. Using the case study method, I endeavored to understand how and why people were developed within the context of OMF.

RESEARCH DESIGN

One of the key principles of the case study method is the collection of multiple sources of data. Use of multiple sources of data promotes triangulation,9 which insures the validity of the study (Yin 1994:92; Fontana and Frey 1998:73; Krueger 1988:40). Figure 3 demonstrates the interactions between all of the sources. In the following sections, I introduce the multiple sources of data I used, and after explaining these sources, I outline my data collection procedures.

Figure 3. Convergence of multiple sources of evidence (adapted from Yin 1994:93).

Desktop Research

Researchers working with qualitative interviews and focus groups must first immerse themselves in the subject matter. Therefore, careful historical analysis and study of documents related to the research topic ensues before questions are written or data is collected (Rubin and Rubin 1995:76). For my study of OMF, I devoted one tutorial to its organizational history and specifically focused on the current organizational changes that resulted in the Member Development Program (MDP). For this I used the following books and documents: (a) biographies of Hudson Taylor; (b) a book on the first one hundred years of CIM/OMF (Lyall 1965); and (c) other archival records of OMF, namely the Central Council Minutes, and all the documents pertaining to the introduction of the MDP. 10

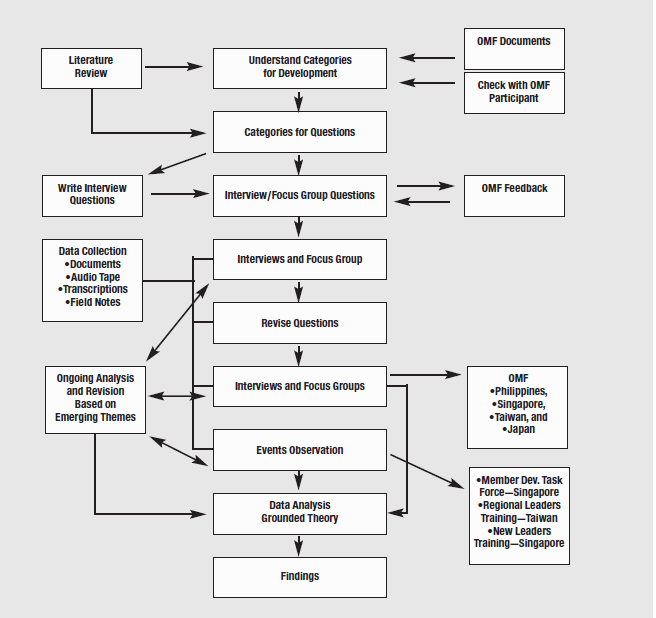

I verified my analysis and understanding of OMF organizational history and the organizational change with the two OMF leaders who introduced the MDP and corrected any misunderstandings. After this phase of analysis, I formed initial questions for both the in-depth interviews and focus groups. After getting feedback on the questions from my mentors and other OMF leaders, I settled into a flexible design that allowed adjustment and followed emerging themes as they arose (Rubin and Rubin 1995:44). Figure 4 demonstrates this procedure.

In-depth Interviews

Kvale defines qualitative interviewing as “understanding by means of conversation” (1996:11). In other words, qualitative interviewing allows the researcher to ascertain the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of people (Rubin and Rubin 1995:1). This method is most appropriately used in situations where an in-depth understanding is best obtained through examples and narratives or when a complex, interrelated, event-oriented situation needs to be understood (51). All hold true for the OMF case.

The OMF study was designed as a topical study. Topical studies “explore what, when, how, and why something happened” (Rubin and Rubin 1995:196). In the OMF case, I studied what, when, how, and why development happened. The interview questions related to the root of the research questions I was exploring; these were adjusted accordingly following subsequent analysis (Kvale 1996:129).11 (See Figure 4.)

The study also called for a semi-structured, iterative interview in which questions were asked according to major themes that emerged from the background study. The semi-structural nature of the questionnaire kept the interviews focused on major themes, but also allowed me to follow additional themes as they emerged (Kvale 1996:27).12 While the basic interview questions were the same for everyone, I stratified the questions or added questions based on the expertise of the interviewee (Rubin and Rubin 1995:207). For example, some OMF members were more astute in their understanding of organizational dynamics. Therefore, I pursued this topic to a greater depth with them. And certain OMF leaders were privy to the “behind the scenes” changes that brought about the MDP. Interviews with them allowed me to explore the nuances of the program and the philosophical foundations of the change.

Relational Procedure

Concerned about the sometimes objectifying procedures of research and the dominant role the interviewer plays in interviews, researchers today are moving toward a more relational and reciprocal environment for interviews. There is “no intimacy without reciprocity” (Oakley 1981:49).

Following the lead of qualitative interview experts, safe environments were created for building relationships, which led to open sharing of ideas and experiences (Rubin and Rubin 1995:12). I conducted the interviews by first informally “breaking the ice” with humor, small talk, and sharing personal history (Fontana and Frey 1998:67). I especially tried to establish the fact that I was a learner and we would be talking about a topic of mutual interest. I then conveyed the ground rules of the interview by giving the purpose of the study and requesting the use of a tape recorder for accuracy (Kvale 1996:125-128). While following the general interview guide, I probed for additional information or pursued clarification when necessary (Rubin and Rubin 1995:208). Follow up questions were asked if the interviewee said something surprising or different from many of the answers I had previously received (212).

Sample

In general, qualitative researchers design their study to explore their topic deeply from diverse points of view (Rubin and Rubin 1995:76), usually working with small samples of people who are in the context of the topic to be studied (Miles and Huberman 1994:27). The investigator chooses people who have knowledge about the situation being studied, are willing to talk, and represent a range of viewpoints (Rubin and Rubin 1995:66). For the interview sequence, the researcher moves from the general to the more specific (Miles and Huberman 1994:28). Therefore, for the OMF study, I selected the persons to be interviewed with these criteria in mind.

As mentioned earlier, OMF is a complex organization with members from over twenty-five different countries. These members have ministered with OMF from one to over forty years and work in a variety of contexts. As OMF exists in a hierarchical structure, people in the organization have varying responsibilities. A handful of leaders have championed the MDP.

With this in mind, I asked my contacts in OMF13 to invite participants for the interviews according to diverse nationalities, varied lengths of service, and different ministry positions. I also asked them to invite individuals from every level of the hierarchy, and key leaders who implemented the change which moved OMF toward a more developmental bias. I sought to have both a variety of participants and those who were information-rich (Miles and Huberman 1994:28). These interviews took place in the key locations of Singapore, the International Headquarters, and OMF’s largest fields (countries where the largest numbers of OMF members serve—Thailand, Philippines, Taiwan, and Japan).14

Focus Groups

Focus groups are similar to interviews with some variation on purpose and procedure (Fontana and Frey 1998:54). Focus groups promote the stimulation of ideas around a given topic. A focus group is “a carefully planned discussion designed to obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest in a permissive, nonthreatening environment” (Krueger 1988:18). Focus groups transport rich data, since they function on the principle that attitudes and perceptions related to programs or services develop partly through interaction with other people.15 The group interaction produces candor, and often the sharing of ideas stimulates others’ ideas and experiences (23, 44). Continuing with the rationale for qualitative research, focus groups are particularly helpful when the goal is to understand people’s views on an experience, idea, or event (20).

Procedures

The procedures for developing focus group questions and conducting the groups are similar to interviews. The researcher writes questions that will illuminate the purpose and major themes of the study. Again, the investigator bases these questions on a thorough background study (Krueger 1988:52). However, the researcher must also be adept in group dynamic skills to successfully conduct focus groups. Small talk before the group interview begins must be noticed, and body language is important as well (112). The researcher must also keep one person or a coalition of people from dominating conversation and encourage all participants to share (Fontana and Frey 1998:54).

Similar to the in-depth interviews, the first few minutes of the focus groups are crucial for setting the stage of safety and openness (Krueger 1988:80). Here, I handed out a brief background, which described my personal history. In the focus groups I also handed out my general questions so participants could anticipate and follow along. This allowed them to write down thoughts as prompted by their reflection or others’ comments. At the end of our time together, I also encouraged participants to write down any additional thoughts or comments they hadn’t felt comfortable sharing in the group context. I then gathered all the questions.

Sample

Like in-depth interviews, focus groups endeavor to uncover people’s varied experiences. Focus group selection, however, also operates within a principle of commonality. Participants chosen for focus groups should have experienced the topic in question—for OMF, all participants had experienced development in one form or another (Krueger 1988:26).

Trying to concentrate in OMF’s major fields, I once more opted for focus groups in Thailand, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Japan. Knowing that maximum variation is the preferred method, I again asked for the participants to be varied in nationality, ministry assignments, leadership, and ministry experience (Maykut 1994:56). All of these constraints were met. The Japanese focus group contained mostly high-level leaders.16

Events Observation

The third point in the triangle of multiple sources is events observation (Figure 4). “Observation consists of gathering impressions of the surrounding world through all relevant human faculties. This necessitates direct contact with the subjects of observation” (Adler and Adler 1998:80).

Event observation enables researchers to understand the context from which a program operates. On site researchers have an increased understanding as they experience the event and can see things that may not be included in the documents or participants’ description of a program (Patton 1990:203, 204).

Researchers using observation operate from one of three membership roles.17 For this study, I took on the role of “peripheral-member-researcher.” I endeavored to be close enough to the situations to understand the perspectives of the insiders (often by asking clarifying, debriefing questions after the event), but I did not become a member of OMF.

The events I chose to observe were key meetings and training seminars where development was discussed or an environment for development was created. I attended a meeting of the Member Development Task Force in Singapore. I describe the MDTF as the “think tank” for development in OMF. This is the main body of people who plan development events, create curricula, and facilitate development in OMF. While the task force remains intact, a portion of the task force has now become a department in the organizational structure of OMF. The MDTF functions under this department. I also observed two leadership training events: the Regional Leadership Training Workshop (RLTW) in Taiwan and the New Leaders Introduction Course (NLIC) in Singapore.18 Each event was four days long, thus providing ample opportunity to observe training and to learn through informal discussions.

DATA COLLECTION

Qualitative research is only as good as the methods used to collect and retrieve the data and the data analysis itself. If a researcher had an excellent field experience, yet could not understand or logically use the data, the study would be ineffective. Data management is “the operations needed for a systematic, coherent process of data collection, storage, and retrieval” (Miles and Huberman 1998:180). In this section, I demonstrate the data collection methods used in this study to ensure high quality data and reliability.19

Overall Approach

Let me begin by describing my overall approach on the field and analysis actions (Seidman 1998:110). In each of the five countries I stayed in the OMF Mission Homes, which gave me the opportunity to meet more OMF members than I had originally anticipated. Besides the formal interviews, focus groups, and training events, there were many opportunities to talk informally with other OMF members during meals and free time. This gave me a more holistic view of OMF missionary life.

I varied the interview schedule between mornings and afternoons. As stated earlier, I began the interviews and focus groups by briefly sharing my personal history and pilgrimage leading to this research topic. During the introduction, I also gave the ground rules concerning confidentiality and group dynamics. Each interview lasted anywhere from 45 to 90 minutes, depending on our synergy of ideas and the interviewee’s verbosity. The focus groups were all approximately 90 minutes; two groups met in the morning (Thailand, Philippines), one group met in the afternoon (Japan), and one group met in the evening (Taiwan).

At the end of the day, I wrote my personal notes and did ongoing analysis (Krueger 1988:112; Maykut 1994:46). If I made any changes to methodology, I also noted this in a journal. When I finished in each country, I sent personal emails thanking everyone who participated in the research project.

During the days that I observed training events, I followed the schedule of the training event and worked on my personal notes in the evening. While the training was taking place, I took notes that related to what the training demonstrated about development and my impressions of why the trainers were choosing to teach certain things. This was a good time to notice how the values for member development matched with the actions of the organization. I also noticed interactions and possible opportunities for development, as well as barriers to development. If I needed clarification, I met with the presenters and/or participants later.

Specifics of the Database

Yin describes the development of a database as including four items:

- Notes: the investigator’s notes from interviews, observations, and/or document

- Documents: any documents related to the study and acquired during the

- Tabular materials: documentation of survey, quantitative data, or other types of “counts.” (This was not a quantitative study so tabular results only occur in data analysis by observing the frequency of )

- Narratives: responses to open-ended questions (Yin 1994:95-97).

My database includes all four of these items.

Documents

Before beginning the fieldwork, I had already collected a binder full of archival records related to the development of persons in OMF. These are organized in chronological order as an overview of this organizational change. They informed the development of research questions. While on the field, I acquired other documents as well. These included meeting agendas, training notes for participants in training events, the booklets that have been published for personal development, and OMF’s Personnel Handbook.

Notes

Scholars suggest many approaches to field notes; there are no set methods for this aspect of data collection. However, field notes lead the way to qualitative analysis and are therefore crucial (Patton 1990:239). Following Schatzman and Stauss’ approach, I took four different types of notes (quoted in Schwandt and Halpern 1988:77):

- Field Notes: these included my personal notes during the interview, focus group, or event as well as contact summaries for each interview and focus

- Methodological Notes: I wrote these notes before the fieldwork began and continued writing them while out in the These notes included methodological decisions made such as shifts in sampling and interviewing strategies.

- Theoretical Notes: After the research day, I reflected on emerging themes and made memos to myself regarding hypotheses and/or evolving category

- Personal Journal: Here I kept track of my personal feelings and intuitions as well as how I was coping with culture stress. Basically I tried to document anything that might influence my experience or interpretation of data.

Tabular Materials

Since this is not a quantitative study, the data does not include a lot of tabular materials. In data analysis, however, frequencies of answers to questions were noted.

Narratives

All of the interviews and focus groups were taped and later transcribed. I gave the transcriber instructions to transcribe every word—even repeated phrases or sentences. I asked her not to transcribe verbal pauses such as “ums” and “uhs” since I was not conducting a sociolinguistic or psychological study (Kvale 1996:169, 170). Upon doing a spot check for accuracy in the transcripts, I noticed that the transcriber had missed key words, phrases, and sometimes, whole sentences. Therefore, a friend and I listened to all the tapes and filled in the missing elements.

The data collection process proceeded as designed with OMF. By the end of the interviews, focus groups and events, saturation point was reached and no new information was being uncovered (Maykut 1994:62). I report more about this in the next section on data analysis.

DATA ANALYSIS

Qualitative research methods require inductive, ongoing analysis, continuing analysis after data collection, and eventually theorizing analysis. In other words, the qualitative approach calls for constant analysis! For this study, I endeavored to follow this pattern and used grounded theory methodology as an overall framework. The next sections demonstrate this approach.

Overall Approach

Strauss and Corbin describe three approaches for analyzing qualitative data:

- Present data without analysis: This is similar to a journalist presenting the facts of participants’

- Reconstruction of data: The researcher accurately describes what he/she has understood from the

- Theory building: The researcher inductively derives theory based on the data (1990:22, 23).

I structured this study to produce theory. This required that I do ongoing analysis of the data looking for patterns and themes, subsequent coding, and finally, conceptualizing theory.

This was an emergent study; theory emerged as the data was collected and analyzed, and was not predetermined (Maykut 1994:46). Ongoing analysis aided the process of theory building; during the interviews and focus groups, I listened to discover themes and concepts (Rubin and Rubin 1995:57). Frequently the data presented something surprising. I pursued this element in subsequent interviews to see what would emerge (Seidman 1998:11).

In general, I followed Miles and Huberman’s process for analysis. Briefly, their procedure entails noting patterns and themes, clustering conceptual groups, making contrasts and comparisons, subsuming particular to general, and creating theoretical coherence (1998:187). This process took place both on the field and afterwards, resulting in a “grounded theory” emerging from the data.

Grounded Theory

Simply stated, grounded theory is “the discovery of theory from data” (Glaser 1967:1). Grounded theory is one of the qualitative social research methods that uses systematic procedures to develop theory connected to phenomena (Strauss and Corbin 1990:24). One chooses grounded theory for a variety of reasons. First, conceptualizing helps to understand the actions of subjects. Second, this understanding enables researchers to gain perspective on behavior. Third, theory can be applied in other situations (Glaser 1967:3; Glaser 1992:13).

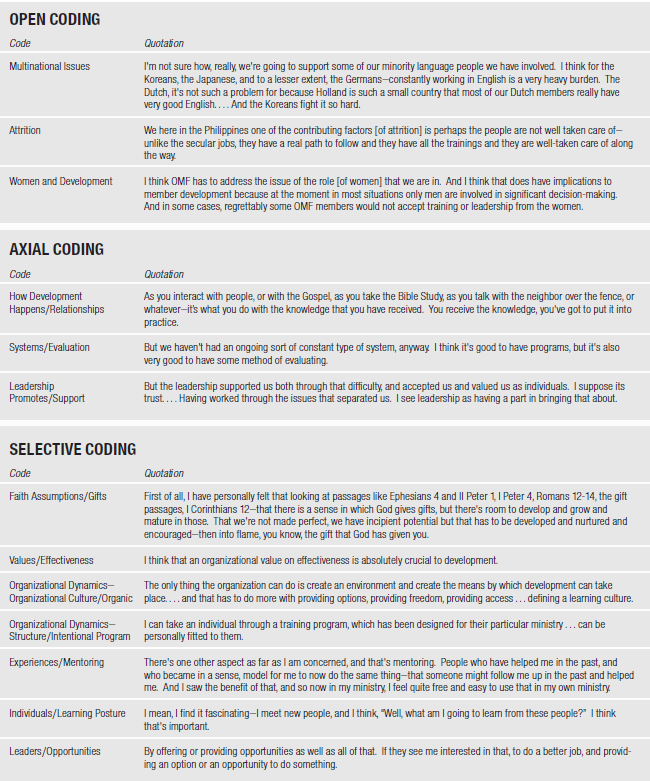

Table 1. Examples of Open, Axial, and Selective Coding

The process of grounded theory research can be divided into three categories: data collection, coding of data, and theory building (Glaser 1978:16). All three of these processes happen concurrently although in my research, much of the coding was done after data collection. Each day, however, I kept track of my ideation and theory building in the memo section of my field notes (83, 84). 20

I have addressed the data collection procedures above. I reiterate here, however, that data collection continues until saturation, that is, when no new categories of data are produced (Glaser 1967:61). Coding is the process of categorizing people’s responses into similar ideas and concepts (Rubin and Rubin 1995:238). These ideas and concepts are “coding families.” The coding families can also include various processes that have occurred in peoples’ lives (Glaser 1978:74). I first used an open coding method in which codes were assigned—line by line— throughout each transcript (Glaser 1992:48). In this process, I identified concepts along with their properties and dimensions, resulting in categories and subcategories of data (Strauss and Corbin 1990:101). I then grouped the coding into these categories and subcategories (axial coding) (123). As analysis continued and theory began to emerge, I pursued selective coding which allowed me to integrate the data at a higher level and moved me closer to producing theory (143). Finally, through conceptualizing codes and noticing the frequency of participants’ specific answers related to codes, I proposed a theory for development. Table 1 shows examples of each level of coding.

Throughout the process of coding, I used the constant comparison method. Experiences from individual’s lives were compared to the experiences of other individuals. This established the underlying uniformity and highlighted varying conditions (situations in which experiences were different) (Glaser 1978:49).

As mentioned earlier, data management (the collection and retrieval of data) is crucial for quality analysis. Computers provide excellent aid for the coding and retrieval process since they are designed to function with structure (Richards and Richards 1998:216). For the coding process and theoretical analysis,21 I used a qualitative computer program called QSR NUD*IST (Qualitative Solutions and Research’s Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing Searching and Theorizing). I chose this particular program since it works on a “code-retrieve-system” and allows one to manipulate categories as theory emerges (236).22 Using NUD*IST, researchers have the option of processing data in two ways. It can be analyzed by coding whole documents and retrievals can be done by context, proximity, and sequencing searches. Or data can be grouped into hierarchical trees, which allows the researcher to create and manipulate categories of data to explore emerging themes. Each time the researcher makes a change to the categories or manipulates the hierarchical tree, the program documents the change to produce an audit trail (237).

Data analysis for this study led to a theory through the hard work of coding, analyzing, recoding, and conceptualizing. Grounded theory, using the constant comparison method and looking for emerging theory, proved to be the best methodology.

STEPS TAKEN TO ENSURE QUALITY OF RESEARCH

One ensures the trustworthiness and quality of research through the design of data collection and analysis procedures. In this section, I address the measures I took to ensure the quality of research by speaking to the categories of trustworthiness, reliability, and construct, internal, and external validity.

Lincoln and Guba (1985) give several methods of data collection that strengthens trustworthiness. In their approach, researchers should first of all use multiple sources of data collection for triangulation. In the OMF study, I used archival records, other documents, in-depth interviews, focus groups, and events observation. Second, researchers should have a clear audit trail. My audit trail consists of four types of field notes, a binder of documents related to OMF Member Development, tapes and transcripts of the original interviews/focus groups, coding via a computer program, and various reports used for analysis based on the coding. Third, work in a research team is most effective. My study did not permit the use of a team. However, I conferred throughout the study with other research associates, including my committee and other colleagues, who understand the qualitative method. Fourth, researchers should check their data with participants. From the beginning I checked my understanding of OMF’s MDP and clarified impressions from the data. This culminated in several key OMF members reviewing a rough draft of the dissertation. Finally, the grounded theory process itself strengthens trustworthiness. All emerging theory can be traced back to data following the trail of open, axial, and selective coding.

Many qualitative researchers use the categories of reliability and internal and external validity to ascertain the quality of research (Lincoln and Guba 1985:290-292; Rudestam and Newton 1992:38, 39; Yin 1994:33). Yin also uses the category of construct validity in addition to the other three. While there will be some repetition with the above more general approach to trustworthiness, I will use these categories to address the issue of quality in this study.

Construct validity relates to establishing correct data collection and reporting operations (Yin 1994:33). Three tactics are used to increase construct validity: multiple sources of evidence, an audit trail, and having key informants review a draft of the report (34, 35). I planned for and executed all of these tactics.

Internal validity relates to causal connections within the data (Lincoln and Guba 1985: 290). Researchers check causal inferences by carrying out structural corroboration such as spending adequate time with participants, exploring participants’ experiences and comparing it with other participants’ experiences, peer debriefing, and revising methodology as research evolves (Rudestam and Newton 1992:39). All of these criteria were included in the study.

External validity establishes the domain to which the study’s findings can be generalized (Yin 1994:33). At present, the findings for this study can be generalized for OMF. A preliminary connection was made with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship to see if the theory could be applied in their organization. Anecdotally, it seems that the theory could be applied.

Finally, reliability corresponds to the replication of the study in similar situations (Rudestam and Newton 1992:38). Researchers code data and leave an audit trail in ways other researchers could understand and potentially replicate under comparable circumstances. My coding and audit trails are clear. My documentation procedures are logical, straightforward, and based on well- documented qualitative research methodology (Yin 1994:37). It seems other researchers would produce the same results. A colleague at another university reviewed the methodology and agreed.

SUMMARY

The OMF study followed qualitative research methodology and incorporated a case study method that included documents, in-depth interviews, focus groups, and events observation for data collection. Grounded theory methodology was used for data analysis with the aid of a qualitative research computer program. Figure 5 captures the complete methodology. The left side of the diagram delineates my actions. The center of the diagram shows the overall research process, and the right side of the diagram shows my interactions with OMF.

FINDINGS

Analysis of the data 23 using the grounded theory method revealed the significant themes related to development within OMF. Based on the data, these themes were integrated into a theoretical model for developmental organizations. This theory is descriptive of the OMF data and potentially diagnostic for other organizations desirous of incorporating development and as well as diagnostic for organizational analysis in general. In the next sections, I present the integrated model.

Overview

I highlight from the onset that development in OMF is intimately connected to people. Members of the organization create environments where development can occur. Members initiate processes that result in personal development. And members experience transformation as a result of the processes of development. Every aspect of development is tied to people simultaneously creating, receiving, and promoting development. People initiate even the seemingly inanimate functions of organizational structures, culture, and systems that promote development.

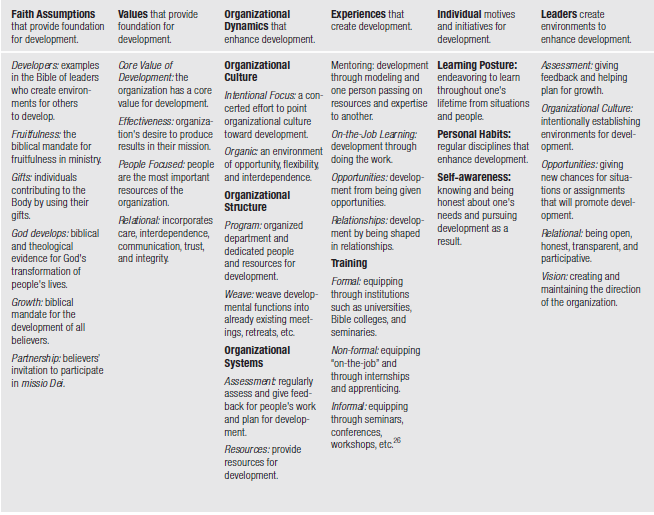

Having briefly established the importance of people, the data also reveals that the interrelationships and interconnections between six key components enhance development. These components are faith assumptions, values, organizational dynamics, developmental experiences, individuals, and leaders. In this overview, I briefly describe the components and give an explanation of their interrelationships.

Six Components

The data from the interviews and focus groups (and confirmed in the events observation) demonstrated six components required for development of members in OMF (see Table 1).

- Faith assumptions are the theological and biblical foundations for development. Although this particular area was sometimes difficult for OMF members to articulate, all except one of the interviewees and all but one of the focus groups expressed faith assumptions that support, or call for, the development of

- Values are implicit or explicit beliefs regarding development that result in actions of They are the “oughts” in an organization (Schein 1985:14). Every interview participant and each focus group explained values that promote development.

- Certain organizational dynamics—such as organizational culture, structure, and systems—promote development and insure its longevity in an Each focus group articulated examples of organizational dynamics, as did all interviewees except one.

- Experiences are events or situations in which people were Every person interviewed and each person in the focus groups had had experiences in which they were developed.

- The component of individuals relates to what individuals do to develop All but two interviewees recounted personal habits or self-initiated learning for their development.24In one focus group, personal initiatives for development were not mentioned.

- Finally, the component of leaders connects to what leaders do to promote the development of All but one interview participant expressed the importance of leaders in their development.

The Integrated Model: Interrelationships of the Six Components

Figure 6 illustrates a systems model that integrates the six components and demonstrates their connections and interactions. Beginning with the left side of the diagram (causal loop 1—internal paradigms),25 faith assumptions influence the formation of values. People’s biblical and theological premises produce certain beliefs about life and ministry. If individuals, for example, believe the Bible calls for Christians to grow toward full maturity throughout their lifetime, they likely hold values for development. Likewise, value formation further strengthens and deepens faith assumptions. Developmental values highlight and illumine theological beliefs and biblical texts. They increase developmental faith assumptions. For example, a value for everyone contributing to the organization shows the biblical premise for all gifts in the body being used.

On the right side of the diagram (causal loop 2—external actions), various organizational dynamics produce experiences in which people are developed. For example, if an organization structures developmental items in each of their regular meetings, this creates developmental experiences. On the other hand, developmental experiences often cause the creation of develop

- For the other two interviewees, my informal interactions with them outside the interviews indicated they intentionally develop Individual self-motivation seems to be key for everyone.

- In systems thinking, elements never exist in isolation, but “always comprise a circle of causality, a feedback ‘loop,’ in which every element is both ‘cause’ and ‘effect’—influenced by some, and influencing others, so that every one of its effects, sooner or later, comes back to roost” (Senge, Kleiner, Roberts, Ross, Smith 1994:113). “The world is a loopy place where cause and effect go around and around like a long winding spring of causality” (Boyett and Boyett 1998:106). mental organizational dynamics. People who have experienced development will create the dynamics necessary to institutionalize development in an organization. For example, they produce systems that provide resources for development or they create a department within the organizational structure that promotes and insures development throughout the organization.

As mentioned before, development happens in the lives of and through people; therefore, the diagram also illustrates the essential role of people (causal loops 3 and 4—interaction of people with internal paradigms and external actions). Moving counter clockwise and starting at the bottom of the diagram (causal loop 3), leaders shaped by faith assumptions and values create developmental experiences and organizational dynamics. These dynamics and experiences create environments for individuals’ development. Individuals, having been developed, incorporate into their lives developmental faith assumptions and values. Moving clockwise and starting at the top of the diagram (causal loop 4), developmental faith assumptions and values held by individuals also produce developmental dynamics and experiences. These in turn cause leaders to experience and continue to promote development as well as strengthen the developmental faith assumptions and values of the organization. In healthy organizations, change is initiated from the grassroots as well as by the leaders.

All of the six components connect and interact in causal loops. The culmination of these relationships produces developmental processes, which in turn produces a developmental organization.

Specific Aspects of Each Developmental Component

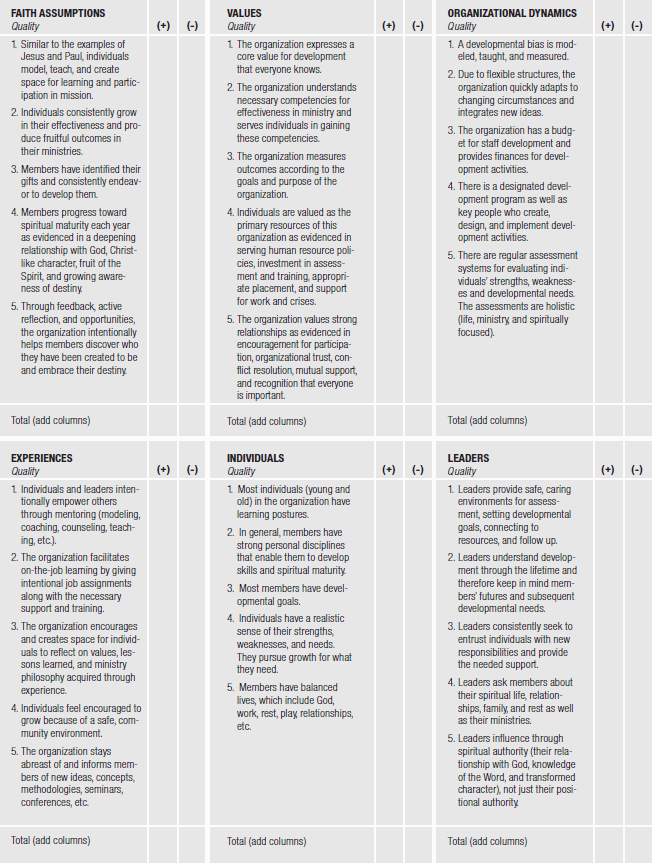

Having introduced the causal relationships between the six developmental components, we now interact regarding the elements of each component. Not only did the data expose significant components necessary for development, it also revealed that each of these components had more specific, repeated qualities or elements. Table 2 shows all of the components with their specific qualities. Table 3 shows the frequency of occurrence of the qualities in the data. Keep in mind that there were fourteen interviews and four focus groups. I give the data from events observation in the description of each component’s element.

Table 2. Components and Their Specific Qualities

EXPLANATION OF SPECIFIC DEVELOPMENTAL COMPONENTS

The Organizational Leader and the Sage

“Is experience the best teacher?” the bright young leader asked the sage. “Can I develop as a leader from experience?”

“Some people have said that experience is the best teacher,” replied the sage. “But some experiences don’t teach.”

“So experience is not the best teacher?”

“Not exactly that,” said the sage. “It is just that not every experience offers important lessons.” “So where do I learn? What experiences will be helpful to me?”

“It is the experiences that challenge you that are developmental,” the sage responded, “the experiences that stretch you, that force you to develop new abilities.”

“Oh, I get it,” said the manager. “When I am really pushed to my limits by an experience, I will learn.

Is that it?”

“Not exactly,” the sage said. “Challenge is important. Our limits need to be tested. But even when we are challenged we don’t necessarily learn.”

“So,” the manager said, looking a bit puzzled, “you mean that I can have the right kind of experi- ences—challenging experiences—and still not learn?”

“That’s right,” the sage responded. “You only grow from challenging experiences when you have the ability to learn from them. Not everyone does. As T. S. Eliot once reminded us, ‘some people have the experience and miss the meaning.’ There are some people who learn hand over fist from challenging experience. Others learn little, if anything. One must be able to learn the lessons and create and act upon values from experiences.”

“I think I’m getting it,” said the leader. “I have to have experiences that challenge me plus the ability to learn from them. I also need to form values and act upon those values even as I experience challenging situations. Is that it?”

- Mentoring is also an informal method of training, but since mentoring proved to be such an important element in the data, I gave mentoring a separate

“Not exactly,” the sage replied. “We don’t learn or grow in a vacuum. Most of us are part of a larger group or organization. Sometimes we have the good fortune of receiving feedback and support for our growth; sometimes we don’t. We need to get feedback from others and take the time to reflect on our expe- riences and values. Feedback and reflection allow us to assess how we are doing, what’s working, and how we need to change. We also need acceptance, advice, and encouragement from others and support from our organizations if we expect to grow. We simply cannot do it all alone. We need relationships. We need people with whom we entrust our lives.”

“Let me see if I understand. When I value growth and development, when I avail myself to challenging experiences, when I take seriously learning from those experiences, and when I get support and feedback from key people in my organization, I can develop. It all seems so complicated.”

“It is a bit complicated. Being stretched and challenged is not easy. Diversity and adversity are the keys to growth, and both challenge us. None of us like to operate out of our comfort zone. And it takes time. Years, in fact. And a lot of pieces have to fit together: challenging experiences, organizational sup- port, individual readiness. We used to think it was easier, that single events were developmental—a single event of training, for example. But that understanding was inadequate. Development happens over time as part of a process or a system. There is still a lot we don’t know about how people develop. But we have learned a lot and we are learning more all the time. And the good news is that we can learn and grow and change.” (adapted from McCauley, Moxley, and Van Velsor 1998:1-3)

The complexity of development emerged through the study. The development of persons is influenced by a large variety of factors and their interactions. With the integrated model, I have captured this complexity in the components that influence development and their interactions. The model demonstrates that development in organizations is a system of components each interacting with and influencing others as demonstrated by causal loops. In this next section,

I demonstrate the implications of this model and the data by again addressing the components.

Faith Assumptions

Both the data and literature point toward development as one of God’s agendas. In fact, the Bible is replete with developmental stories, metaphors, and theological constructs. The narratives of people’s lives demonstrate the process of transformation. Sovereign God uses every circumstance—good and difficult—to shape people’s lives and move them toward their created identity and purpose. The OMF interviewees pointed out that various sections of the Bible speak of God transforming believers into the image of Christ. Ultimately, through a growth and transformation process, we will be like Jesus.

It seems that in its broadest sense, God’s purpose for us as people, is to take someone who’s not at all like God, and to transform them through a developmental process into someone who is just like Jesus. (S2)27

Thus a young man with little training becomes a prophet to the nations (Jeremiah) and rugged fishermen become insightful leaders of a movement (Peter, Andrew, James, and John). One OMF focus group participant spoke of Jesus as a developer:

Jesus spent time with the disciples, and then sent them out to do things, [and] then brought them back in and [to] discuss what they had done. And then sent them out again. He promised that the Holy Spirit would be with them, and that He wasn’t deserting them. So I think it is comparable to us coming to the field and doing something, and then in some way, coming back together and reviewing and then going out and doing more. (PFG)

Even the expansion of the Kingdom of God could be considered developmental in cosmic and individual ways. As the reign of Christ expands, more transformation at all levels ensues— political, economic, physical, and individual. God is in the process of extending his reign, and the parables liken it to the ways in which a small mustard seed grows to become a large tree sheltering many living things or to yeast which expands to leaven bread dough (Mt. 13).

God calls people to serve him here in OMF—a calling of virtually evangelizing East Asia’s millions. And each one of us are disciples of the Lord Jesus, and each one of us [has] different gifts and abilities. And we have to see where we fit in the picture in the best possible way. (P1)

God will grow his Kingdom and carry out his purposes until ultimately all things will come under his authority resulting in the new heaven and the new earth. God’s reign intersecting with humans’ lives results in deliverance, healing, and salvation. This too has a final outcome in our resurrection and total transformation into the image of Christ.

While organizational literature typically has not included faith assumptions, there is a growing movement in the genre to address this important aspect of organizations (Mitroff and Denton 1999: xiv). One assumes that Christian organizations automatically include faith assumptions and a focus on spirituality. However, these organizations often lack intentionality regarding the development of faith assumptions. OMF members in the interviews and focus groups pointed toward biblical and theological themes that provide motivation for development. I have labeled these themes “faith assumptions” in order to incorporate both aspects of Bible and Direct quotes from interviewees have specific abbreviations that identify the country and the Other abbreviations identify the focus group of each country, e.g. the next quote. theology. The emergent themes under the faith assumption category are developers (the Bible tells the story of numerous persons who develop others, e.g., Paul), fruitfulness (the Bible expects fruitfulness, e.g., Jn. 14-17), gifts (all Christians are called to minister and use their spiritual gifts, Rom. 12, 1 Cor. 12-14), God develops, growth (Bible declares that growth, especially into Christ’s image, is a normal expectation), and partnership (related to effectiveness, we are called to partner with God in his Kingdom mission). “God wants people to be fruitful, and that is part of the commission. . . . I choose you that you bear much fruit” (S3). This means that ministers must be effective in their endeavors. With this premise, fruitfulness “is progress toward God’s desired end for this ministry” (S5).

From an organizational perspective, fruitfulness is a stewardship issue. The organization must do all it can to equip its members to be fruitful.

Fruitfulness is all that stewardship is about. Jesus told the story about the steward who produced nothing and said he was most unfaithful. And I think Pete Wagner has a quote in one of his books, you know, “God is not pleased with sowing without reaping, with fishing without catching,” and it’s the whole thing that God’s intention in the world is to make a difference. (S5)

With development as such a key theme in the Scriptures and since it includes expansion of the Kingdom, which includes transformation, it makes sense that missions organizations should be characterized by development as well. The stories and theology of development in the Bible should inspire our faith assumptions and values. They should also bring insight for understanding the process of development as it is seen in the lives of many individuals in Scripture. Finally, the Bible should centrally inform methodology concerning development. For example, development happens through an encounter with God and through the community of believers. Development also happens when there is an honest awareness of need and a willingness to entrust one’s life to God and others to have that need met.

Values

Faith assumptions form the foundation for values and values strengthen and deepen faith assumptions in a causal loop (see Figure 6). Generally speaking, true values elicit connecting actions. De Pree describes this interaction of values and actions as connecting voice with touch (1992:5). Assuming that faith assumptions and values are developmentally focused, they become the bases for developmental actions. Otherwise a developmental agenda is likely to become a passing fad. The data revealed four individual and corporate values that promote developmental actions (development as a core value, effectiveness, people focus, and relational focus). I say “individual and corporate” because individuals embody the following four values, yet the values are widely held organizational values within OMF. The following sections highlight these values and where appropriate weave in informing literature.

Development as a Core Value

It is more likely that organizational change toward a developmental bias followed by developmental actions (organizational dynamics and experiences) will happen if development is a core value. A true core value informs decisions for resources and strategy. It also becomes a measurable outcome.

Knowing that development was unlikely to infiltrate the organization without intentional focus, OMF leaders created core values that institutionalized development.

If it didn’t become a core value of OMF, you’d be fighting it all along. It would be seen as an appendage. . . . I felt that [the only thing that] would really drive or fuel [development] was a core value. So, we did a thing at central council where we developed a set of our core values. (S4)

In fact, two of their five corporate principles relate to development (Principle 2 on member effectiveness and Principle 3 on diversity).

Core values are the organization’s essential and enduring tenets. They are the general, guiding principles that should never be sacrificed for expediency or short-term gain (Porras and Collins 1997:73). If the development of people is important, the organization will have—either implicitly or explicitly—core values related to development. Belief in the importance of development promotes the establishment of organizational procedures and norms to ensure continuous development (McCauley, Moxley, and Van Velsor 1998:16). Plans, strategies, and goals flow from the purpose of the organization and the core values. Therefore, development of people will likely ensue if the organization has a core value of development. This has certainly been evidenced in OMF as the core value of development has birthed intentional developmental actions—plans, strategies, and goals.

Porras and Collins point out that enduring organizations have a core value for development that gets expressed in the recruitment, training, and development of employees (1997:193). Effective organizations must invest in people (Kanter 1997:142). In other words, investing in development provides longevity and productivity for the organization; therefore, it is an absolute must for organizations desirous of remaining effective.

Effectiveness

Organizations who truly want to fulfill their God-given purpose will help their members be effective in their ministries. As mentioned before, one of the five core organizational principles of OMF is member effectiveness; therefore, much of what the organization sponsors for development seeks to achieve the goal of helping missionaries be more effective in their ministries. “Come join us and we want to work together to see that you are effective” (S3). Organizations keep their purpose central by enabling their people to successfully carry out the purpose. This implies that organizational leaders have an understanding of what it means for members to be competent in their areas of ministry. It also means that the organization will provide, network, or connect individuals with the knowledge, skills, and experience necessary to be effective.

The literature supports this value for effectiveness as well. Organizations must stay focused on their purpose—the reason for which they exist—and make sure they eventuate outcomes consistent with their purpose (Porras and Collins 1997:73). Organizations that do not ask diagnostic questions about outcomes signal that outcomes are not taken seriously (Engel and Dyrness 2000:152). One of the ways the organization ensures focus on the purpose is to help members be effective in carrying out the purpose. For De Pree, effectiveness naturally follows when organizations encourage people to reach their potential—both personal and institutional potential. Therefore, the organization must provide excellent training and educational opportunities (1989:19, 85).

Finally, fulfillment of purpose requires that the organization sets standards for measuring effectiveness, communicates these standards, and provides feedback in line with the standards. A constant-learning environment is required. The interviews and focus groups pointed out that effectiveness incorporates learning—having a learning posture throughout one’s lifetime.

Presumably, a learning posture would enhance effectiveness. “I think actually for missionaries, the best missionaries are the ones that keep learning and have that kind of zest for learning” (T7).

“I think people who are growing are going to be much more effective in ministry” (TAFG). Ultimately, a learning posture prevents plateauing and keeps the missionary vital and effective. All of the events underscored this fact and were even designed with an effectiveness goal— serving OMF members so they can be more effective in ministry.

People Focus

“We see it as important to develop our members. We don’t want to just use people; we want to develop them” (S4). Thus an OMF leader captures this important value. An organization that seeks to be developmental must have as a primary value a focus on people. It must view people as the primary resources of the organization.

It is true that people are the greatest assets of the organization, and the purposes of the organization are carried out by and through people. Yet leaving the focus of this value as “people are the greatest assets” may lead to a pragmatic use of individuals similar to viewing them as interchangeable, dispensable cogs in a machine. Here the mentality would be “we develop our people to use them better.” It is true that God expresses and culminates his purpose in establishing the Kingdom of God. It is also true that God gives organizations individual purposes in carrying out his larger mission, and therefore individuals within organizations partner with his purposes. However, God is able to carry out his purposes and at the same time bring ultimate good for people’s lives. In this sense, he is the God of “and,” not the God of “or.” By orchestration of the Holy Spirit, individuals develop into who God has created them to be “and” they partner with God in his mission. With God the two are not mutually exclusive, therefore, they must not be in mission organizations.

Data from the interviews, focus groups, and events repeatedly highlighted this people- focused value. The value, in their minds, incorporates several different ideas. Besides viewing members as the primary resources, it also moves the organization away from using people to valuing them for who they are as God’s unique creations. Yes, the organization has a purpose of “urgent evangelization,” but people are not to be viewed as simply means to that end. Their whole being must be developed; otherwise they will lack resources and burn out. “Value the person as a person—not the person as something that produces an end result” (JFG).

Organizations with God-given purposes must join God in adopting the “and” posture as well. God brings people into organizations to fulfill purpose and for transformation (and this happens under the umbrella of God’s purpose and the organization’s purpose). Both processes are inter- woven, happen simultaneously, and are sometimes in a causal loop. They should not be separated or stand in opposition to each other.

Relational Focus

The theme of relationships and their influence on development weaved through the findings. The data and literature reveal the importance of relational values. An organic organizational culture is expressed in interconnections, i.e. relationships. Entrusting oneself to relationships can provide important developmental experiences. This theme suggests that organizations characterized by an ambiance of “relationships” will more likely be developmental. Organizations that hold relational values such as open communication and sharing of information, working through conflict, and team building will likely encourage participation and ownership, which in turn produces development. These organizations will more likely have relational environments of grace characterized by openness and support, providing safety for taking risks, succeeding, and even failing. This, too, enhances development; individuals are more likely to move toward stretching challenges that require development, and they are more likely to be honest about their developmental needs. Finally, within the context of safe, committed relationships, people are more likely to speak into one another’s lives and bring support, encouragement, and correction. In the company of people who are committed to one another, it is easy to embrace growth and dream large dreams (God dreams). This, too, promotes development.

The most cited value from the data was relational focus (35 citations in 9 of 14 interviews and two of four focus groups). OMF members felt that if there were relational values, development would assuredly follow, and they experienced this as the number one value leading to their development. Of course a relational value is multifaceted and incorporates such things as care, interdependence, communication, trust, and integrity.

OMF members spoke of a general atmosphere of care, support, and encouragement as leading to their development. Concretely speaking, this value is lived out by being sensitive to one another, looking out for the needs of another, and speaking well of each other. Some OMF members describe this as a posture of serving. Ultimately, this value and the ensuing actions lead to a fellowship of trust, which naturally provides a safe place for development. “If we have more fellowship, we can be open and come together. And we can . . . build trust” (T1). “I think that organizational trust is very important for development as people trust their leaders—that fosters a climate where growth is more possible—you are not as afraid of failures” (T7).

Trust explicitly leads to interdependence, which is another factor in the relational focus value. OMF members often describe the organization as a family (“we are a family”—TA-FG), and therefore entrust themselves to others for input and support. When they face difficult times, they call upon other OMF members to pray and get help.

Interdependence extends to others outside the organization. OMF members also learn from their fellow missionaries and people in other agencies. “There are other organizations in the field . . . and I also get to talk with their leaders here in Manila. . . . I think it promotes development because you get to learn other systems” (P2).

The relational value extends to include communication. With a relational focus, there is a sense that people have freedom to be open and honest—a freedom to be transparent. They know that their input counts and trust that they are being heard.

“Openness and honesty includes choice of leadership. . . . It includes policy changes. . . . It includes recommendations on people’s future ministry” (TFG). Interdependence implies that every person’s contribution is needed and therefore there is a value for participation. Ultimately, this communication promotes development, as there is a safe environment in which people share honestly, seek the support they need, and serve the growth of others.

Recent scientific discoveries, which have then been applied to organizations, compel leaders within organizations to concentrate on relationships. For example, it was discovered that organisms, while maintaining their individual identity, exist in large networks of relationships that help shape their identity. This principle, called autopiesis (self production or self-making), describes the process whereby organisms create self through their intimate engagement with others in a system (Wheatley 1999:20). This principle holds true for human beings. Value for relationship creates relationships, which in turn transforms individuals. In fact, many studies have shown that peer relationships are important avenues for growth and development (McCauley and Douglas 1998:184).

A value for transforming relationships grows in the context of “environments of grace” (Thrall, McNicol, and McElrath 1999:29). Here, relational values extend to include authenticity, trust, and safety. Individuals welcome the input of their friends, colleagues, and team members when grace characterizes the culture. The opportunity for true transformation occurs with the value and action of vulnerability—individuals entrusting themselves to others (81). With such vulnerability, individuals receive others’ influence and submit to others’ strengths.

Of course a relational value assumes interdependence, also highlighted in the data. Teams function more effectively with a mutual acknowledgement that each member needs the other (Thrall, McNicol, and McElrath 1999:47). In speaking about the relational value and specifically interdependence, participants noted the need to support and care for one another. It is characteristic for people in healthy organizations to care for each other and demonstrate trust (Adizes 1988:170). However, a relational value of interdependence extends beyond care and support to value diversity. All must contribute their gifts and talents in order to have an effective organization (De Pree 1989:25, 26). Teams, leaders, and the organization as a whole must recognize that they need each other. De Pree calls for organizations to value “covenantal relationships” in which everyone has the right to be needed, involved, influential, and accountable.

It is interesting to note that key values for development focus on people and their interactions. Development takes place because of people, and the results of development are manifested in people.

Beliefs encourage behaviors—actions (Johnson 1998:65). Development occurs when people hold developmental values. In the next sections, I present the data that focuses on developmental actions (external actions) that flow from faith assumptions and developmental values (internal paradigms). Keep in mind the integrated model (Figure 6), and see Figure 7 for an illustration of the interaction between faith assumption/values and actions.

Organizational Dynamics

The data and literature reveal important factors for organizational design and development. There are a number of implications for organizational culture, structure, and systems.

Organizational Culture

It follows that if an organization has a core value related to development, people within that organization are likely to create a culture that intentionally focuses on development. That is what OMF has done. The most important organizational dynamic from the data (with 57 occurrences) was the intentional culture of development.

In OMF, we’ve had a unique . . . top-down driven development. From the general director down, he’s saying, “This is important, we will do this.” He models it, encourages it, and sponsors it. So it’s not just a human resource department off in a corner fighting for airtime. (S4)

One OMF member points toward the importance of this organizational culture:

The only thing the organization can do is create an environment and create the means by which development can take place. . . . And, so that has to do more with providing options, providing freedom, providing access . . . defining a learning culture. (S5)

Flexible, free, growing, innovative, interdependent, and open are all words that describe living systems. Organizations are living systems because they are made of people, and they have a life and history of their own. They are essentially organic. But many organizations (sometimes especially Christian organizations) do not act organically and can be described as rigid, tightly structured, layered in hierarchy, controlling, and uncomfortable with change. Individuals in non-organic environments find it difficult to develop.

For obvious reasons, organizational cultures of control inhibit development. The underlying motivations behind control are fear and power. This leads to environments of secrecy, hoarding, and lack of freedom.

Organic systems exhibit growth and innovation. Thus an organic culture also provides freedom for members to pursue what they need for growth in an open manner. “It’s okay to say, ‘I need help because I don’t know how to do this’” (S2). A living system will continue to adapt and grow in order to adjust to changing external factors.

Innovation for effectiveness in ministry is another key aspect of an organic organizational culture. “A number of our people have moved into roles, have started new things . . . because of their gifting and what they felt was needed” (P4). This is crucial for development and crucial for the missionary endeavor. Because innovations often do not work as planned, an organic culture also assumes a safe environment where it is safe to fail. “[Form a] culture with the value that it is safe to fail. It’s okay to struggle” (T2).

On the other hand, an organic organizational culture promotes development through inter- connection, sharing of resources, and innovation. The connections promote transformation through feedback and sharing resources. A climate of innovation ensures development as individuals try new things and consequently are stretched and challenged. People in these environments develop because they are encouraged to grow and contribute meaningfully to the whole. Their participation influences who and what the organization is, which boosts morale and encourages individuals to continue to take responsibility to grow.