Leadership credibility is hard to gain, but easy to lose—even with a longstanding record of achievements. In a national election year, leadership credibility is the underlying dynamic moving a whole nation. Who is this candidate? Can we trust her or him? Will they be able to deliver what they promise? Will they be able to create a new capacity in the nation to tackle seemingly insurmountable problems? In the wake of the epidemic loss of trust after the highly published downfall of companies like Enron and MCI, after church scandals involving religious leaders like the fall of Ted Haggard, then President of the National Association of Evangelicals (Thornburgh, 2006), and the collapse of financial institutions around the world, it is no wonder that people’s trust in its public leaders is at an all-time low (Gergen, 2008; Kouzes & Posner, 2002; Rosenthal, 2007).

In crosscultural contexts, the development of credibility often becomes an elusive dimension of leadership, because the filter of culture colors even the most basic aspects of a leader’s life and work. This is even true for leaders who are highly effective in their own culture. When encountering cross-cultural barriers they find themselves in an unpredictable context no longer responsive to their preferred ways of leading. Despite best intentions, their lack of cultural competence seems to neutralize their personal effectiveness and often torpedoes their ability to build organizational capacity, which is one of the main ingredients of leadership credibility.

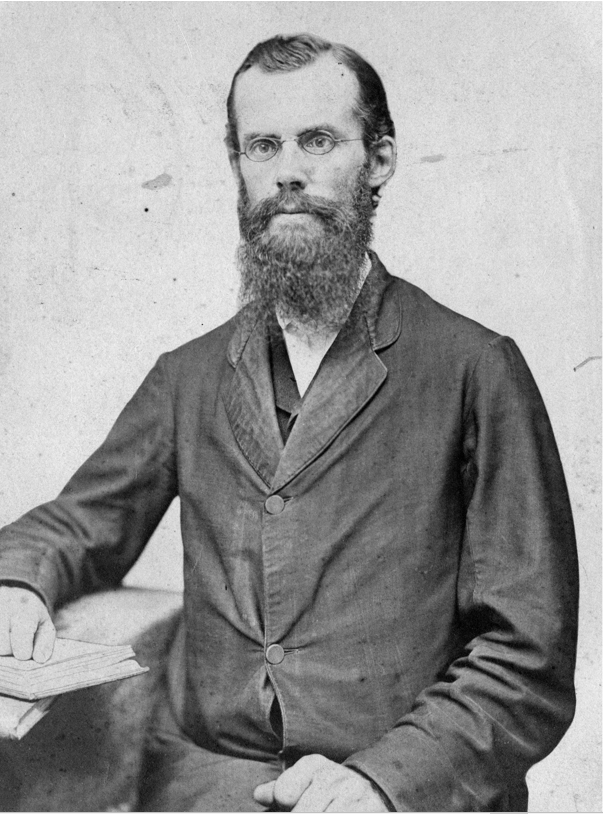

These dynamics are not new to our time. Missionaries have struggled with these realities ever since Jesus sent his disciples to the ends of the earth (Acts 1:8). When Christians sought to take the Gospel to new fields, they faced the unpredictability of unknown cultural dynamics. This has also been the experience of one of the earliest Seventh-day Adventist missionaries, John Nevins Andrews, whose name is now linked to the first Seventh-day Adventist university—Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan. Growing up as an Adventist Christian in Austria, I always heard the name of J. N. Andrews spoken with admiration. In my mind he was one of the most formidable leaders of the early Adventist church, remembered as the one who opened the door of world mission to this church and who gave his life for the cause of world mission.

When I came to Andrews University as a student, I hoped to research some of the original sources to gain a sharper picture of the leadership of Andrews. With the growth of Adventism slowing in Europe, I wanted to see if there were any lessons from history for today. The James White Library catalogue at Andrews University listed several papers that had been written about this revered leader. More importantly, I found an MA thesis written by Gordon Balharrie (1949), in which he tried to assess the contributions made by Andrews to the Adventist church. As I started to read its weathered pages, I was struck by the fact that it documented a rather uneven picture of Andrews and considered his work in Europe almost a failure. This conclusion surprised me. So I decided to read the available correspondence between Andrews and contemporary leaders in North America and the reports of his work submitted to the Adventist Review. What I found was not the hero that I was looking for, but a person struggling to overcome enormous obstacles that made his work in Europe very difficult.

At the time I did not know what to do with my findings. Leadership credibility is based on trust and the ability to create the organizational capacity to accomplish a mission. Here was one of my heroes whose work I had always admired, hopelessly criticized as a leader of the European mission by his contemporaries, firmly pushed aside while he was dying almost brokenhearted and convinced that he had failed thousands of miles from home.

What was even more intriguing was that nobody had really assessed Andrews’ work as a leader from a cross-cultural perspective. In 1983, at the occasion of the centenary of his death in Basel, Switzerland, thirty scholars from North America and Europe met at a symposium at the French Adventist Seminary at Collonges, France, to study aspects of his life and his contributions to his church. Referring to E. G. White’s often quoted statement to the Swiss leaders around Andrews, “We sent you the ablest man in all our ranks, but you have not appreciated the sacrifice we make in thus doing” (1878), Joseph G. Smoot, SDA historian and then president of Andrews University and expert on Andrews’ life, remarked at that time: “How able was the ablest is still, however, an unanswered question” (Leonard, 1985, p. 3). The most important papers of the symposium were published in 1985, by Andrews University Press, under the title J. N. Andrews, The Man and the Mission (Leonard, 1985). It constitutes probably the most objective analysis of Andrews’ life and work to date. The different papers treated many aspects of his biography as a scholar and a missionary and shed light on his personal life. But the assessment of his contribution as a missionary leader remained tentative.

I now teach leaders from all over the world from many different persuasions in the Leadership program at Andrews University. It is a program that often uses Kolb’s Learning Cycle (Kolb, 1984) as a model to explain how leaders develop competency by reflecting on their experience. I encourage leaders to use their everyday work context as a laboratory for experimenting with new leadership skills. Leaders may go through devastating failure or exhilarating success, but unless they develop skills to learn from these events by reflecting on them (reflection on action) and become more aware of how they react in different situations (reflection in action), experience is not a good teacher (Schön, 1983, 1987).

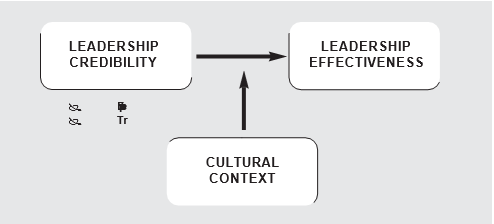

Reflection is not only helpful in our own lives but allows us to benefit from the experience of others. In this study I will use the complex experience of Andrews’ leadership as a starting point to reflect on the question of what makes credibility such an elusive commodity in cross-cultural contexts. According to Hughes, Ginnett, and Curphy (2009), credibility is “the ability to engender trust in others” (p. 356). It is made up of two components: (1) expertise and (2) trust. Expertise includes the knowledge and repertoire of skills needed in a specific context to be successful, an in-depth knowledge of the organization, and a good understanding of the larger context in which the organization operates. The trust component of credibility is based on the values modeled and encouraged by the leader and the strength of the relationship the leader is building in an organization. But in the case of Andrews, these two dimensions were moderated by his entry into a new culture (see Figure 1). I will use these two dimensions to analyze Andrews’ rise to prominence in the early Adventist movement that eventually led to his dispatch as the first official missionary of the Adventist church and which made him the trailblazer of an impressive stream of missionaries pouring into the world to plant the Adventist church in over 200 countries around the world (Maxwell & Rother, 1986).

Figure 1: Leadership credibility as a factor dependent on culturally appropriate expertise and trust

THE RISE OF ANDREWS AS A LEADER IN THE ADVENTIST CHURCH

The role of Andrews in the early Adventist church must be seen against the backdrop of history. The Adventist church traces its beginning to the Millerite Movement in the 1840s, a revival movement centering on the expectation of Christ’s imminent return which climaxed in what has become known as the “Great Disappointment” of October 22, 1844. At that time the movement disintegrated into a number of groups. Out of one of the smallest groups of dispersed believers emerged the nucleus of the Seventh-day Adventist church. This group tried to understand the theological implications of the non-return of Christ and struggled to come to grips with their own existence and identity in a new way (cf. Damsteegt, 1977, pp. 212-222; Schantz, 1983).

Born in Poland, Maine, on July 22, 1829, Andrews received Jesus Christ as his personal savior in his youth in 1843 (Andrews Correspondence, Feb. 8, 1877). He joined the Adventist movement in 1846 after reading a tract on the seventh-day Sabbath and accepted its message together with his parents (Spalding, 1961, pp. 1:121-122). The role of the Sabbath in Christian life and doctrine would become a life-long preoccupation of Andrews. His first written contributions to Adventism came in 1849 as a report of one of the “Sabbath conferences,” gatherings during which the early Adventists dialogued about the meaning of their experience (1849). A year later he wrote a short article titled “Thoughts on the Sabbath,” published in December of 1850 in the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald (RH), the new Adventist newspaper.

He joined the itinerant ministry of the movement in 1850, holding meetings in 20 different locations and writing for the church paper; he was ordained as a minister in 1853. But the strain of his work almost broke his health and led to his retirement from the ministry for several years. It was Ellen and James White who revived the commitment of the young minister in 1859 (Neufeld, 1996, p. 1: 68). Soon his talent as a writer and apologist for the Adventist faith made him one of the most prominent Adventist leaders. His careful biblical scholarship was influential in shaping some of the key doctrinal positions in Adventism, such as the understanding of the question of law and grace, the Sabbath, and the interpretation of biblical prophecies (Neufeld, 1996, p. 69). Andrews’ clear teaching and writing style and thorough biblical argument did much to build the identity of the young Adventist movement. In the 23 years between his first article and his departure as a missionary to Europe, 150 articles bearing his initials A. appeared in the Review. Dealing mainly with the distinguishing aspects of the Adventist faith (Cottrell, 1985, p. 106), these articles made him the architect of Adventist doctrines (Mueller, 1985). Probably his most influential book is his History of the Sabbath, first published in 1861, revised in 1873 and 1887 (the last edition posthumously), in which he traced the history of seventh-day Sabbath-observing groups in the history of the church. And through this book he became “the Adventist pioneer of historical research on the Sabbath question” (Heinz, 1985, p. 131).

Andrews also contributed in another way to the young Adventist movement. As their numbers grew, it became clear that they needed to adopt an effective organizational structure that would bring together the different independent congregations and groups and allow for a more coherent and systematic approach to supporting clergy and evangelism (Mustard, 1988; Oliver, 1989). James White, the visionary organizer and promoter of the Adventist church structure, found in Andrews a level-headed supporter (Neufeld, 1996). In 1863, the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists was founded in Battle Creek, Michigan. Only four years later, Andrews was asked to serve as its third president, an office he occupied for two years (Smith, 1868, 1869). He was succeeded by his brother- in-law, George Butler. In 1869 he became editor in chief of the Review during a dispute between another brother-in-law, Uriah Smith, and James White (Walker, 1869), which developed into a full-fledged leadership crisis that engulfed the Adventist church in the early 1870s and “came close to separating friends of long standing” (Smoot, 1985, pp. 49-50). Again Andrews’ supportive role in helping solve a crisis and solicit more understanding for the heavy responsibilities of James White proved crucial. N. Andrews was one of the important leaders of the young Adventist church. His credibility was established through years of faithful ministry. He played a central role in the shaping of the Adventist identity and organizational structure, and he was enormously productive as a scholar and writer. He was occasionally called to special roles such as his visit to the Provost Marshall General in Washington, D. C., to represent the Adventist church’s position on non combatancy during the civil war (Graybill, 1985, p. 31). These factors show that Andrews’ credibility as a leader was well established on the basis of his expertise and years of trust. But how did Andrews become the one chosen to spearhead the worldwide mission enterprise of the Adventist church?

The year 1863, marking the official birth of the Seventh-day Adventist denomination and church organization, also saw one of the first known references to the “world wide” mission of the church (White, J., 1863, p. 197). Yet the church was not ready for a mission to the whole world. It was preoccupied with the Western frontier in America, which was proving very responsive (Vande Vere, 1986, pp. 72-81). Many considered a witness to immigrants enough of a world mission. In 1859 Uriah Smith, the influential editor of the church’s general paper, had reasoned that a more cross-cultural proclamation of the Adventist message was not necessary “since our land is composed of people from almost every nation” (Smith, 1859, p. 87). But this reasoning was soon to be proven totally inadequate by “providential” circumstances when some of the newly won immigrants sent publications of their new-found conviction back to Europe and thus started cells of interested persons (Schantz, 1983, pp. 244-245; White, J., 1862, p. 40). The existence of such cells started a chain of events that eventually led Adventist leaders to call on American Adventists to widen their vision of the mission of the church (cf. General Conference Committee 1863:8) and to send out missionaries.

The plot thickened when Czechowski, a Polish former Franciscan priest who had accepted the Adventist message, urged the General Conference to send him as a missionary back to Europe (cf. Correspondence in RH 1857-1862). When he was turned down repeatedly, he finally solicited the sponsorship of non-Sabbatarian Adventists, returned to Europe and planted the first Seventh-day Adventist companies of believers in Northern Italy, Switzerland, Southern Germany and Eastern Europe. Hiding his true identity, he planted Sabbatarian groups who were not aware of other Sabbath-keeping Adventists until 1867, when they started to correspond with Battle Creek, the Adventist headquarters at the time.

News of the existence of such groups came to American Adventists as a shock. It led them to reconsider their former disapproval of Czechowski’s vision of a mission to Europe. It was European Adventists who insistently begged for a missionary from the General Conference. The president of the General Conference at the time of their first appeal for a missionary was none other than J. N. Andrews (Neufeld, 1976, p. 495). It was he who gave their spokesman, Johannes Erzberger, a course in Adventist theology while he stayed at the Andrews household in Rochester in 1870 (Neufeld, 1976, p. 430; Zurcher, 1985, p. 202). Andrews was also the one who raised the question of a mission to Switzerland at the General Conference session of 1870 (Zurcher, 1985, p. 203). While the church was not ready to send out an official missionary, these incidents do illustrate that Andrews’ appointment to Switzerland did not come as a surprise move, but followed a pattern of events. Evidently Andrews’ personal interest in the European cause and his reputation as the “most scholarly minister and writer” of the movement (Vande Vere, 1986, p. 87) made him the most logical choice for the European mission enterprise.

The appointment to Europe did not come easily for the young church, which was heavily engaged in expansive efforts on the western front (California and Oregon) (Vande Vere, 1986). For a time it seemed that Andrews, for want of an official decision, would have to actually leave for Europe informally (Zurcher, 1985, p. 204). His private correspondence with White in the spring of 1874 indicates that Andrews actively prepared

for his departure for Europe, although the official action was not taken by the General Conference until August (Andrews Correspondence February-April, 1874). He finally sailed from Boston to Liverpool en route to Switzerland on September 15, 1874, accom- panied by his two children, Charles (17 years old) and Mary (13 years old). His wife had died on March 18, 1872 (Neufeld, 1976, p. 35). His departure opened a new phase of Adventist missions, in which the Adventist church expanded geographically “into all the world” (Oosterwal, 1972, p. 25).

Our review of the effectiveness of Andrews as a leader makes it clear that he was seen as the most prolific theologian of the church, a most effective evangelist, and a trusted administrator. Figure 2 tries to capture this conclusion. As Andrews embarked on the greatest adventure of his life, the question would be how these qualities would serve him as a pioneer missionary in the old continent.

ANDREWS AS A MISSIONARY LEADER

There is no doubt that Andrews sailed to Europe with high expectations. While he did not know exactly what to expect, he knew of the existence of several groups of believers. As the immigrant Adventists’ population in America grew—by 1877 they were estimated to compose about a tenth of the membership (Vande Vere, 1986, p. 87)—so did the number of tracts crossing the ocean to tell of the new-found faith. One group that was a forerunner of the German Adventist church were independent Christians gathered by J. Lindermann after 1850 in Vohwinkel in A weaver by trade, he had through independent Bible study within his group discovered some of the truths Adventists held dearly: e.g. believers’ baptism, the Sabbath, the Second Coming (Pfeiffer, 1985, pp. 261- 265). The existence of all these different groups raised the expectations of Adventist leaders in Battle Creek for the mission of J. N. Andrews, who was confidently sent out as one “who has nobly defended the truth from his very youth” (White, J., 1874, p. 100).

But when he arrived in Europe he found himself in a completely new context that challenged everything he had been accustomed to. While today’s would-be missionaries have access to an enormous library of cross cultural expertise, Andrews went without the benefit of these tools and soon faced a situation that soon tested his adaptive qualities. Being a great learner and scholar, he was able to adapt to personal challenges, such as the language challenge, amazingly well. But the organizational and wider cultural challenges proved more difficult to cope with. Eventually they immobilized Andrews to the point of virtual standstill, a fact often deplored by his contemporaries in America.

One of the first problems he encountered was the diversity of languages and cultures in Europe. Andrews realized the importance of learning the French language well enough “so as to speak it correctly and to write it grammatically” (1874d, p. 106). He decided, with his children, to allow only French in their home apart from 5-6 a.m. This discipline in the family led to their mastery of French in an amazingly short time.

It is good if we remember how Andrews saw his mission to Europe. Writing from Switzerland to the Review, he reports the mission of the Adventist movement to the Swiss believers as giving to the world the warning of the near approach of the judgment, and in setting forth the sacred character of the law of God as the rule of our lives and of the final judgment and the obligation of mankind to keep God’s commandments. (1874b, p. 172, 1874c, p. 196)

To warn as many people as possible was the perceived objective. Adventists saw this final preparatory message embodied in the messages given by the three angels of Revelation 14. That is why Adventists often refer to their message as the Three Angels’ Messages or the Third Angel’s Message (Andrews, 1892; Damsteegt, 1977, pp. 165-242). Some might wonder if Adventists, in their eschatological focus and their preoccupation with the law of God, did not forget the most important aspect of the Gospel Commission: the Gospel itself. Andrews would have answered that in the basic Christian doctrines (repentance, faith, new birth, salvation, etc.) “we are in perfect accord with all evangelical Christians” (1879b). The Swiss believers seemed to understand this mission objective.

But the cultural barrier proved more formidable. The Europeans, with a diverse, long-standing cultural history, did not show any inclination to accept proposed changes of customs, habits, or lifestyle. Andrews had difficulties dealing with this seeming unwillingness of European Adventists to change their way of life. Already in his first report to the American Committee, he complains: “I tried prudently but faithfully to change or to correct various things, but found it was like plowing upon a rock. I grieved those that I tried to correct, but produced no change” (Andrews 1875:36).

Without the presence of other experienced leaders around him, Andrews was left with his own instincts. As a scholar he was used to advancing ideas and expecting others to adjust to them. When people resisted his efforts to reform them, Andrews’ rather sensitive nature had a tendency to shy away from conflict. He measured the efforts of those around him with a perfectionist eye and soon found himself isolated. Given the major transitions Andrews had suffered—during the last couple years as he had buried his wife, uprooted his family from America, and found himself as a single parent trying to pioneer the work of the Adventist church in an unfamiliar environment—it is admirable that Andrews seemed undeterred in the first few months of his stay. Accustomed to the freedom of American life, he must have found it strange that he had to register for a residential permit, or to ask for permission from local authorities to hold a public meeting. Andrews’ successor, Whitney, was especially disturbed about the fact that Germans listening to a religious discourse did not find it out of taste or disrespectful to be served beer and to smoke during the discourse (Historical Sketches, 1886, p. 19).

Europe’s religious scene differed quite considerably from the American. State churches did not allow any new religious groups to use public facilities to proclaim their new doctrines. Sometimes there were difficulties in obtaining permission to preach in a church. It was not uncommon for American evangelists to find that in some places they simply had no access to any public hall other than dancing halls (Historical Sketches, 1886, p. 18). In France, it was also forbidden to sell any publications not bearing the stamp of a Catholic archbishop in Paris (p. 27). These hindrances eventually led Andrews to visit Paris to contact the French government to request a more liberal policy towards their public work. This move eventually proved successful (pp. 27-28).

Given the existence of scattered Sabbath-keeping believers, often unknown to him, Andrews used mainly three methods to establish contact with them and arouse new interest in the Adventist message: advertisements in popular newspapers all over Europe, public meetings, and literature. None of these methods were new to him. The first method he had adopted from the Seventh-day Baptist minister Jones, whom he had visited in London on his way to Basel (Andrews, 1874a, p. 142). The other two methods had been successfully used as the main means of spreading the Adventist message in America. While the advertising campaign did not bring many concrete results apart from limited correspondence with a few French-speaking individuals to whom Andrews sent English tracts (1875a, p. 93), it did convince him that he needed literature in European languages.

Conducting public meetings proved more successful. Together with Erzberger, the only ordained worker besides himself, Andrews traveled to Prussia in the spring of 1875 to visit Lindermann’s group. Evidently, Andrews had come to reap the harvest quickly. But after an initial warm welcome and agreement on many theological issues, a crisis developed over the question of the millennium (Andrews, 1875d, p. 116). Andrews apparently extended his original plan to stay only two weeks to four weeks, yet he had to leave feeling unsuccessful. It was Erzberger, who stayed to conduct public meetings, who succeeded in finally admitting the first eight people into the Adventist church by baptizing them on January 8, 1876, in a lake Soon Andrews was really worried about how to contact all the different groups of believers scattered all over the continent: “Sometimes I think, though I dare not affirm it to be certainly true, that I would consent to be cut in many pieces if each piece might become a preacher of Christ” (Andrews, 1875d, p. 116). In January 1876, he was therefore joined by D. T. Bourdeau, a French- speaking Canadian, who became, with Erzberger, one of the most prominent SDA evangelists in Europe (Historical Sketches, 1886, p. 22). But soon Andrews found himself dismayed by Bourdeau’s eccentric personality, which did not fit into his way of doing things. Andrews himself gravitated more and more towards what he knew best: the third method—the publication of literature, which he saw as an ideal medium to reach the thousands and to overcome the limitations of a local preacher. In 1875 he said: “Our work is to be accomplished partly by the living preacher, but principally by publications” (1875c, pp. 124, emphasis mine). And in this I find him in line with what the American leadership considered efficient strategy (White, J., 1875, p. 180).

In August 1875 it was decided to allow Andrews “to establish a printing office” (General Conference Committee, 1875, p. 59). This press would be in addition to Oakland and Battle Creek, the third in the denomination. To document the reason for this decision, a letter from Andrews was quoted:

My first great object to accomplish in Switzerland is the publication of a paper in French. . . . The day which witnesses the publication of a paper in French on behalf of the cause of truth will mark a new era here. The time is at hand when with God’s blessing we will have this. (Andrews, 1875b, p. 60)

A short year later, Andrews’ dream finally came through. The first issue of Les Signes des Temps (Signs of the Times) appeared in July 1876, twenty-one months after his arrival in Switzerland (Andrews, 1876a, p. 29, 1876b, p. 4).

What nobody could really know at that time was that the journal was a kind of mixed blessing at best. Andrews’ intention to have it “filled with the choicest matter; to have it as correct as possible; to have it well printed” (1876) corresponded with his former experience as an editor and writer, but the perfectionist way he went about making it a reality excluded all his coworkers from contributing to this goal. The nationals were not good enough grammarians and not exact enough in their work. Andrews’ unbending standards would eventually lead to a situation where he concentrated completely on the journal while largely neglecting public and personal evangelistic work. This imbalance in missionary strategy did not go unnoticed in Battle Creek.

In June 1877, the General Conference Committee reacted to the situation:

We are pained to learn that Elder Andrews and his son and daughter have been kept from their studies, and Elder Andrews from the lecturing field, to do such work as folding papers, and making tracts, and next to nothing being done in Switzerland and France in gathering numbers to the small membership, and strength to the feeble cause. . . . Something may be gained in publishing in Basel; and a hundred times as much may be lost by shutting Elder Andrews up in that city, away from his brethren. . . . We are becoming terribly anxious about the mission in Europe. If it be true that preaching can do but little without publication, it is quite as true that publications will do little without preaching. . . . Elder Andrews should not be confined to his paper. . . . (General Conference Committee, 1877, pp. 180-181, emphasis mine)

Andrews defended himself on the grounds that he had not been isolated in Basel “from choice but necessity” (1878). This necessity was dictated by his desire to make the journal a quality instrument to reach educated people. But it was nevertheless a sign of his isolation from the very ones he labored for and with.

In addition to the difficulties in the office, Andrews experienced debilitating loss and sickness that greatly hampered his effectiveness. His daughter, Mary, became ill with tuberculosis. In 1878, Andrews decided to take her back to America to be treated. He had been invited to attend the General Conference session and preach the dedicatory sermon for the Battle Creek Tabernacle (RH September 26, 1878). When, two months later, Mary died (at age 17), he was deeply grieved. In addition his brother, William, died in Iowa (Smoot, 1985, p. 60). Fearing that Andrews would not be able to bear the burdens of his heavy responsibilities, Ellen White counseled him to remarry, but he refused to do so (Andrews, 1879a; White, E. G., 1879). He returned to Europe in April 1879 and fell sick only three months later. Nobody at that time could know that this sickness would eventually cause his death in 1883 after a terrible battle. His extremely demanding lifestyle coupled with his inclination to utmost self-denial and economy in eating took their toll.

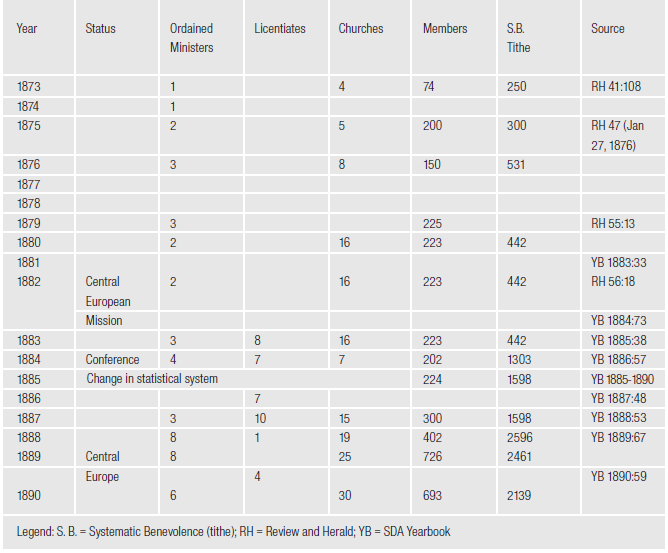

At the time of Andrews’ death in 1883, the Central European Mission showed a membership of 223 members (see appendix). Since Andrews reported 200 members in 1875 (probably an estimated round figure), I have to ask: How effective was Andrews as a missionary? Certainly these figures confirm Andrews’ successor, Whitney’s, evaluation in 1886, when he said: “Although all that measure of success which might be desired has not attended their efforts thus far, yet they have not been without encouraging results. . . . the progress of the cause has been slow,—at times almost imperceptible” (Historical Sketches, 1886, pp. 53-54).

Andrews had a difficult task. He knew of the many possible candidates for the Adventist message. By putting his main focus on printing a journal to reach them, however, he put his confidence into a message that he hoped would advance “by its own merit without the aid that could be rendered by the living preacher” (Andrews, 1883, 522). This must probably be considered as the most serious weakness in his methodology. It reflects his own inclination. He preferred to work with his pen rather than to travel “long journeys backward and forward” to visit the different Sabbath keepers scattered all over Europe (Andrews, 1875c, p. 124). It also shows his lack of identification with the people he wanted to reach. It put an almost unrealistic stress on language learning, which again was done mostly in his own home rather than taking him out to the people he was there to reach. Knowing his tendency to get discouraged and depressed over his own slow progress in language learning, Ellen White told him,

Had you, my brother, worked more through an interpreter in the place of studying so much to speak the language, you would have been working your way into the hearts of the people and into the language too, and kept up better courage all the time. (White, E. G., 1883)

When the Swiss Adventists did not immediately change their lifestyle, he considered them unconverted. When they did not match his own self-sacrifice and sometimes life- threatening economy, he interpreted this as their lacking in missionary spirit (Andrews, 1875 d, p. 116). When they refused to help him because he had antagonized them, he went at it alone, determined “to bring the Swiss brethren up to the standard of the work in America” (Bordeau, 1876, p. 86). Andrews failed to recognize that mission is not only a process of transplanting truths or organizations or importing standard methods from one culture to the other. Mission demands an incarnational approach that allows for the growth of churches properly rooted in the culture in which they have to live (Oosterwal, experienced debilitating loss and sickness that greatly hampered his effectiveness. 1979, p. 200).

Because of his isolation, Andrews also failed to train and develop a broad leadership base. In contrast to his forerunner, Czechowski, who soon involved his followers in becoming missionaries in their own right, Andrews did all the work himself. “You should have done less yourself, . . .”

Ellen White told him openly. “Let every man work who can work. The very best general is not the one who does most of the work himself but one who will obtain the greatest amount of labor from others” (1883).

Andrews, as I have indicated, conceived the Adventist message mainly in terms of distinguishing doctrines. That confrontational approach to other Christians may be seen as an effort of the young church to hammer out its own identity. What in the United States had been a major strength as Andrews prominently defended Adventist positions became possibly a limitation, because it assumed a Bible-literate Protestant readership which simply “constituted a very limited portion of the French-speaking population of Europe” (Sauvagnat, 1985, p. 302). The polemical tone of the paper may not have helped either to break down prejudice and show true identification with those seeking for a better understanding of the Biblical truths.

But this strategy did not stay unchallenged. During her stay in Europe, Ellen White clearly spoke to the working force at the European Missionary Council in 1885 in Basel about the subject of how to present the Adventist message. She urged the European workers not to arouse unnecessary prejudice by confronting others with the peculiarities of Adventism before seeking for common reference points. Instead she pleaded with the European workers to weave sympathy and tenderness into their discourses, to disarm prejudice and show caring love. “Love, peace and joy” she said, are “the credentials of our faith” (White, E. G., 1886, pp. 121, 122, 126, 133, 149). Furthermore, she counseled not to rely on public meetings alone to reach Europeans but to come close to people, visiting them in their homes, something which Andrews had neglected (p. 150).

Andrews’ tendency to criticize others not only made public meetings less successful, but also isolated him from his fellow believers. Finally E. G. White had to defend him— writing to the Swiss believers, she coined that often-quoted phrase: “We sent you the ablest man in all our ranks, but you have not appreciated the sacrifice we make in thus doing” (1878). This statement has become almost legendary in Adventist circles, but it has to be seen in context. Her personal assessment of Andrews’ work was conveyed to him in a surprisingly frank way in her last letter to him (White, E. G., 1883). Very disturbed about his stubborn refusal to accept counsel and his proneness to consider his opinion almost infallible, she chided him not only for having caused his own predicament but also for the slow progress of the work in Europe. She deplored his tendency to ignore criticism and his failure to seek wider consultation in planning for the effective growth of the young Adventist church. By not developing, mentoring and training other leaders, he had brought the mission in Europe into a dangerously precarious situation.

There is no evidence that Andrews ever planted a new church himself. The organizational base of his mission was also very weak. Andrews himself sensed that his efforts were failing to produce the hoped for results. She concluded with these sobering words: “There has not one tenth been done that could have been accomplished had the efforts been more general and more extended” (1883). Andrews made no effort to justify himself. He apologized for his failings.

ASSESSING ANDREWS’ LEADERSHIP

While the literature on leadership in the last decades has produced many different models of leadership (Bass & Stogdill, 1990; Burns, 1978; Yukl, 2002), I have chosen to use a general framework of leadership acknowledged by scholars to be helpful in analyzing the effectiveness of leaders. This transactional framework of leadership was developed by Edwin Hollander (1974, 1978) and has been adapted by Hughes (2009). It sees leadership as a relationship between (a) leaders and (b) followers, in a (c) specific situation. Each of the three elements needs to be understood in order to assess the effectiveness of a leader (see Figure 3).

The data on Andrews’ role as a leader in the years before 1874 show that his leadership was rooted in all three dimensions. His personal strengths fit his role as the scholar-leader—he demanded many hours of secluded research and writing, content to leave to others the more prominent leadership roles. His personal piety and humility made him a sought-after team member of the inner leadership circle; they needed his expertise and trusted his vast theological knowledge. Even though he had no formal schooling, he was a self-taught scholar who evidently had committed large portions of the Bible to memory. Thus his leadership credibility was in part based on a balance between all three dimensions of the interactional model.

But when in 1874 he was thrust into a pioneering missionary leadership role to open new work in Europe, this balance shifted very quickly. In this new environment, his personal strengths as a writer and scholar, which had earned him enormous trust as a leader in the United States (the leader dimensions), now needed to be seasoned with a love for people and tact in a cultural situation so different from anything he had been accustomed to. It must have been painful for the masterful user of language to be handicapped by a temporary inability to use language effectively.

While in the United States he had been the expert theologian, what was needed now was a simple explanation of elementary Biblical truths. What was established practice in the American organization accustomed to democratic committee structures had to be designed from scratch, negotiated through the filters of longstanding traditions and practices. By nature a sensitive yet controlling personality, he did not understand his European counterparts and began to withdraw into the safety of his expertise. But in crosscultural contexts there is no safety to be found anywhere. Even printers and editors functioned quite differently than he was used to. His inability to connect with the Europeans (the follower dimension impacted by the cultural context, the situation) neutralized his effectiveness to the point of paralyzing him.

Andrews’ difficulties as a leader in Europe drives home a lesson that leaders today would do well to learn: Credibility gained in one cultural context is not necessarily transferable. Most of us are totally unprepared to do well in another culture. What is needed above all is a willingness to adapt to new realities and an openness to develop relationships even in the face of culture shock. But while Andrews was willing to sacrifice personal comfort, he was more rigid in dealing with the attitudes and values of his workers and alienated them to the point of frustration on both sides. He attributed their hesitancy to accept his counsel to a lack of spirituality instead of to cultural tensions, a mistake that many missionaries have made after him as well. But while most missionaries have a chance to recover and enjoy the fruit of developing a bicultural bridge, Andrews got stuck in his default personality traits and attitudinal rigidities that contributed to an enormous loss of credibility and that made it difficult for the European Mission to make much progress during his lifetime. Figure 4 attempts to capture this outcome.

In the light of his own and his contemporaries’ assessment of his work in Europe, it may be tempting to write Andrews off as a failure. He certainly felt that way before his death. Historical Sketches, the first systematic account of Adventist mission, also reflects malaise with Andrews’ limited achievements. But time has given perspective to Andrews’ true legacy. For the readers of the Review, Andrews died as “the imperishable symbol of sacrificial devotion to the cause of Foreign Missions” (Balharrie, 1949, p. 93). What is the reason for this? There are probably several reasons.

Andrews’ work marks a watershed in Seventh-day Adventist history. While the high hopes of the Adventist people were not fulfilled by the slow growth of the mission, his work did mark a significant beginning that others could build on. After visiting the European mission to revive the discouraged spirits, S. N. Haskell wrote in 1882, to the Review: “The mission has been started. A good foundation has been laid” (Haskell, 1882, 552). It was Andrews’ reporting system, sending articles and letters faithfully to the Review, that stimulated American Adventists to see the great opportunities opening before them (Leonard, 1985, pp. 225-250). Adventists had also read with great interest contemporary reports from other missionary societies talking optimistically about an almost finished work (Schantz, 1983, p. 253). Now they began to see the magnitude of their own task. During Andrews’ lifetime, work was started in Switzerland, Germany, France (1876), Denmark (1877), Norway, England (1878), Egypt (1879), Sweden and Italy (1880). After his death, eleven new territories were entered by 1890 and another 34 by 1900 (Bauer, 1982, pp. 244-245). In my view, Andrews’ mission sealed the definite Adventist commitment to world mission. This is why Zurcher has called him “the Christopher Columbus of the Advent Movement” (Zurcher, 1985, p. 220).

Moreover, while Andrews’ personality as a perfectionist who demanded similar perfection of others sometimes made it difficult for the Europeans to work with him, there is no doubt about his personal dedication and sacrifice for the work of the Lord. He went with the commitment to give his life to Europe. His promise became a prophecy. It is moving to read the report of how on his deathbed he acknowledged his failures on September 17 (1883) and was reconciled to his European fellow believers. Finally, he signed his last $500 over to the mission. This was all he had, apart from a library that was later given to the Seminary at Collonges, France and Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan (Historical Sketches, 1886, p. 41). Thus he became a model of is sionary dedication that has inspired thousands of Adventists who have gone out as missionaries or supported the worldwide Adventist mission program by their gifts.

Due to the illness of Andrews, the work in his mission almost came to a standstill. But these circumstances provoked Adventist leaders in America to act decisively. In 1882, they sent one of their ablest church planters and organizers to visit the European mission.It was S. N. Haskell, who did much to encourage the workers in Europe. In 1884, the president of the General Conference, G. I. Butler, a strong leader and organizer, came to Europe to effect a thorough reorganization of the work and lift the vision of his people.

In 1885, Ellen White, with her son W. C. White, who was experienced in publishing work, visited the European Mission. They stayed two years and did much to correct the confrontational strategies started by Andrews. This helped to restore unity among the believers. Finally, in 1886, L. A. Conradi, a young, successful German immigrant, took up his work as pioneer leader in Central Europe. Conradi combined the scholarly ability of Andrews with his own executive leadership genius. Like Czechowski, he knew how to deal with the European mind. But he was American enough to be pragmatic in strategy and effective in business and organizational matters (Baumgartner, 1990, pp. 119-123).

Thus, at least in an indirect way, Andrews succeeded in leading the Adventist Church to establish broader approaches and more effective support systems in its mission outreach, a long-term effect which has proven very beneficial for its total mission. The fact that the Adventist church now numbers over 15 million members, most of whom live in non-Western countries, gives Andrews’ sacrifice an almost prescient quality. He may have been a failing man, but his life was no failure.

Through his personal integrity as a sincere and dedicated Christian, willing to sacrifice all for the cause of his Lord, Andrews became an inspirational model for future generations, gaining credibility beyond his untimely death. In a time when the Adventist church in the West is in danger of underestimating the current challenge of the unreached billions, his example of willing sacrifice for mission is again needed. In our time of unprecedented technological possibilities, we forget at our peril that it is not enough to just send our money and our tools, our CDs and DVDs. What is needed is our sons and daughters willing to embody the gospel credibly and to invest their lives to make a difference. His difficulties, however, should serve as a warning that the mission of Christ often leads us into uncharted territories that are difficult and costly to enter, and not without personal identification and intentional contextualization.

References

- Andrews, J. N. (1849, December). Letter to J. White, Oct. 16. Present Truth, 39.

- Andrews, J. N. (1850). Thoughts on the Sabbath. Adventist Review & Sabbath

Herald (Dec. 15), 10. - Andrews, J. N. (1874a). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 44(Oct. 27), 142.

- Andrews, J. N. (1874b). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 44(Nov. 24), 172.

- Andrews, J. N. (1874c). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 44(Dec. 15), 196.

- Andrews, J. N. (1874d). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 44(Nov. 17), 166.

- Andrews, J. N. (1875a). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 45(March 18), 93.

- Andrews, J. N. (1875b). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 46(Aug. 26), 60.

- Andrews, J. N. (1875c). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 45(April 15), 124.

- Andrews, J. N. (1875d). Wants of the cause in Europe. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 46(Oct. 14), 116.

- Andrews, J. N. (1876). Letter to J. White, September 11. Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

- Andrews, J. N. (1876a). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 48(July 20), 29.

- Andrews, J. N. (1876b). [Report about the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 48(June 29), 4.

- Andrews, J. N. (1878). Letter to J. White, January 11. Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

- Andrews, J. N. (1879a). Letter to E. G. White, April 24. Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

- Andrews, J. N. (1879b). Letter to U. Smith, December 25. Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

- Andrews, J. N. (1883). Letter to E. G. White, September 17. Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

- Andrews, J. N. (1883). Report from Basel, Switzerland. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 60(Aug. 14), 522.

- Andrews, J. N. (1892). The three messages of Revelation 14:6-12 (Reprinted 1970 ed.). Battle Creek, MI: Review & Herald.

- Balharrie, G. (1949). A study of the contribution made to the Seventh-day Adventist movement by John Nevins Andrews. Andrews University.

- Bass, B. M., & Stogdill, R. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (3rd ed.). London: Free Press.

- Bauer, B. L. (1982). Congregational and mission structures and how the Seventh-day Adventist Church has related to them. Unpublished DMiss dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary.

- Baumgartner, E. W. (1990). Towards a model of pastoral leadership for church growth in German speaking Europe. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary.

- Bordeau, D. T. (1876). [Report from the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 47(March 16), 86.

- Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

- Cottrell, R. F. (1985). The theologian of the Sabbath. In H. Leonard (Ed.), N. Andrews: The man and the mission (pp. 105-130). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Damsteegt, P. G. (1977). Foundations of the Seventh-day Adventist message and mission. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Erzberger, J. (1876). [Report from the European Mission]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 47(March 1).

- General Conference Committee (1875). [Decision about the establishment of a printing office in Europe]. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 46(Aug 26), 59.

- General Conference Committee (1877). Our European Missions. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 49(June 7), 180-181.

- Gergen, D. (2008). A Deepening Leadership Crisis. Retrieved from http://ac360.blogs.cnn.com/2008/09/30/a-deepening-leadesrhip-crisis/

- Graybill, R. (1985). The family man. In H. Leonard (Ed.), J. N. Andrews: The man and the mission (pp. 13-41). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Haskell, S. N. (1882). The European Mission. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald,

59(August 29), 552. - Heinz, J. (1985). The author of the History of the Sabbbath. In H. Leonard (Ed.), J. N. Andrews: The man and the mission (pp. 131-147). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Historical sketches of the foreign missions of the Seventh-day Adventists (1886). Basel: Imprimerie Polyglotte (republished by Andrews University Press).

Hollander, E. P. (1974). Processes of leadership emergence. Journal of Contemporary Business (Autumn), 19-33. - Hollander, E. P. (1978). Leadership dynamics: A guide to effective relationships.

New York: The Free Press. - Hughes, R. L., Ginnett, R. C., Curphy, G. J. (2009). Leadership: Enhancing the lessons of experience. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning.

Englewood-Cliffs,NJ: Prentice-Hall. - Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2002). The leadership challenge (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Leonard, H. (1985). J. N. Andrews: the man and the mission. Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Maxwell, P., & Rother, S. (1986). Trailblazer for Jesus. Boise, Idaho: Pacific Press.

- Mueller, K. F. (1985). The architect of Adventist doctrines. In H. Leonard (Ed.), Andrews: The man and the mission (pp. 75-104). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Mustard, A. G. (1988). James White and SDA organization: Historical development, 1844-1881. Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Neufeld, D. F. (Ed.). (1976). Seventh-day Adventist encyclopedia (2nd rev. ed.).

Washington, DC: Review & Herald. - Neufeld, D. F. (Ed.). (1996). Seventh-day Adventist encyclopedia (2nd rev. ed.).

Hagerstown, MD: Review & Herald. - Oliver, B. D. (1989). SDA organizational structure : Past, present and future.

Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press. - Oosterwal, G. (1972). Mission possible: The challenge of mission today. Nashville, TN: Southern Publishing.

- Oosterwal, G. (1979). M. B. Czechowski’s significance for the growth and development of Adventist mission. In R. L. Dabrowski, Beach, B. B. (Ed.), Michael Belina Czechowski, 1818-1876 (pp. 160-205). Nashville, TN: Southern Pubishing.

- Pfeiffer, B. E. (1985). The pioneer to Germany. In H. Leonard (Ed.), J. N. Andrews: The man and the mission (pp. 261-271). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Rosenthal, S. A., Pittinsky, T. L., Purvin, D. M., & Montoya, R. M. (2007).

National leadership index 2007: A national study of confidence in leadership. Cambridge, MA: Center for Public Leadership, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. - Sauvagnat, B. J. (1985). The missionary editor. In H. Leonard (Ed.), J. N. Andrews: The man and the mission (pp. 285-308). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Schantz, B. (1983). The development of Seventh-day Adventist missionary thought: A contemporary appraisal. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Smith, U. (1859). Note. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 13(Feb. 3), 87.

- Smith, U. (1868). Business proceedings of the sixth annual session the General

Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 31(May 12), 356. - Smith, U. (1869). Business proceedings of the fifth annual session the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 29(May 28, 1867), 283-284.

- Smoot, J. G. (1985). The churchman: Andrews’ relationship with church leaders. In H. Leonard (Ed.), J. N. Andrews: The man and the mission (pp. 42-74). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Spalding, A. W. (1961). Origin and history of Seventh-Day Adventists. Washington, DC: Review and Herald.

- Thornburgh, N. (2006, Nov. 4). Why the Haggard scandal could hurt evangelical turnout. Time.

- Vande Vere, E. K. (1986). Years of expansion. In G. Land (Ed.), Adventism in America (pp. 66-94). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Walker, E. S. (1869). S.D.A. Publishing Association: Its ninth annual meeting.

Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 33(May 25), 174. - White, E. G. (1878). Letter to the Swiss brethren, August 28. Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

- White, E. G. (1879). Letter to J. N. Andrews, January 27. Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

- White, E. G. (1883). Letter to J. N. Andrews, March 29. Center for Adventist Research, Andrews University.

- White, E. G. (1886). Practical addresses. In Historical sketches of the foreign missions of the Seventh-day Adventists (pp. 119-158). Basel: Imprimerie Polyglotte.

- White, J. (1862). Books to Ireland. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 23(December 30), 40.

- White, J. (1863). The light of the world. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald, 33(June 15), 197.

- White, J. (1874). The cause of present truth. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald

(September 15), 100. - White, J. (1875). Our mission to the world. Adventist Review & Sabbath Herald 45(June 3), 180.

- Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in organizations (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Zurcher, J. R. (1985). Missionary to Europe. In H. Leonard (Ed.), J. N. Andrews: The man and the mission (pp. 201-224). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

Erich Baumgartner is Professor of Leadership and Intercultural Communication in the Department of Leadership and Educational Administration at Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan.