Abstract

Aging is sometimes experienced as a loss of power and influence. Since the proportion of elderly in our society will expand significantly over the next decades, responding to the needs of elders will be a growing challenge for families, churches, and communities. One successful aging strategy with measureable health benefits is to keep seniors involved in the community. In this study, five seniors who are active in serving their community describe the experience of working at a social service agency and the impact of that experience for them personally. The most widely identified benefit was the opportunity to remain actively engaged with people. Participants described a high degree of personal fulfillment and satisfaction as they worked in a team that called upon their skills and challenged them to solve problems and meet challenges. In the process they also experienced a renewed sense of belonging and the simple joys of real servant leadership.

Keywords: Aging, community involvement, servant leadership

“I’ve been put on the shelf,” stormed my father after reading the list of new church officers. Once an active leader, he was now being replaced by younger members. Losing influential status was painful.

This year, according to the Department of Health and Human Services, nearly 40 million people will reach retirement age (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009) and go through similar pain because of their advancing years. Often the pain of physical illness seems paramount, but growing older is fraught with loss: loss of health, loss of income, loss of mental acuity, loss of friends, loss of spouse, and loss of independence, for starters.

In addition to these losses often comes the loss of influence and power, qualities normally associated with leadership (Maxwell & Dornan, 1997, p. 3; Yukl, 2006, p. 3). Throughout his lifetime, my father enjoyed a considerable degree of influence as a respected leader in his church and community. Now a widower living alone at 76 years old, he felt keenly the loss of power and influence. Even so, being left off the church leadership list seemed to reinforce his already standard phrase, “Oh, I’m too old for that.” Unwittingly, he discriminated against himself, a common syndrome plaguing the aging which has been termed, ageism. Ageism is a form of discrimination against people because they are old. Elizabeth Vierck (1988) says that people can suffer discrimination by others, but also by their own attitudes. Sometimes people put themselves on the shelf, believing their own internal message that old people are no longer useful. Sometimes people put themselves on the shelf, believing their own internal message that old people are no longer useful. Churches, families, and society can inadvertently put seniors “on the shelf” while trying to protect their aging loved ones. Seniors are told, “You’re not as young as you used to be. Don’t try that anymore. You spent your life helping us, now you deserve to be served.” This last message can easily be misinterpreted by seniors as, “Don’t get in the way.” As they do less for others their social networks shrink, increasing a sense of powerlessness and irrelevance, further exacerbating aging difficulties.

The question is how to deal with this self-defeating cycle. Paradoxically, while older people may feel less needed and useful, many have unique resources that, if mobilized, can be a great asset to communities who recognize their potential. Leadership scholars like French and Raven (1959) describe these attitudes as a form of influence they called referent power, based on character, integrity, and a genuine interest in others. It is often exercised through role modeling, especially when the person exhibits friendliness and love to those around him. Thus others give the leader power through mutual love and respect even though the leader may not consciously strive to attain it (Yukl, 2006, pp. 154, 155). Since older adults can build on a lifetime of experience, the question is how older adults can be encouraged to engage in social relationships that allow them to use their referent power in mutually beneficial ways.

The Goal of Aging Successfully

Successful aging is defined as maintaining a sphere of influence through living a life of engagement as an older adult. Unwittingly, both my father and his church succumbed to the stereotypical cycle of devaluing seniors as they age. My father’s situation illustrates this self- defeating cycle that starts with real or perceived loss of influence leading to fewer personal relationships, and that gets reinforced by the tendency to devaluate oneself and others, which can inject a painful dimensions into the process of aging.

For most, growing old is inevitable. Someday we will not be reinstated into the roles to which we are accustomed. Will we, like many before us, fall victim to ageism and become increasingly disengaged from our communities? Even though I am still a few seasons away from retirement, I wonder, how successfully will I age?

Terry Jones (2006), a leading proponent of successful aging, theorizes that seniors who embrace elderhood and stay active in their community are physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually healthier than those who do not remain active contributors in the lives of those around them. Keeping seniors meaningfully engaged for others can be a source of improved quality and length of life for our elders (Greenfield & Marks, 2007, p. 13).

Serving Is Healthy

For thirteen years I was director of Portland Adventist Community Services (PACS), a bustling not-for-profit social service agency. I always had more work available than money, so I relied on a volunteer base of retired seniors to donate their time. The agency served poverty level individuals through food, clothing and household item distribution programs, providing free health care for those without health insurance, and offering low cost items through a thrift shop for those unwilling to accept charity.

Volunteers collected food, stocked shelves, and sorted, priced and hung clothes and other items. They worked as volunteer healthcare professionals, non-certified intake counselors, cashiers, and receptionists. Through the years this ever-changing workforce represented hundreds of people, mostly of retirement age. Working with three of those volunteers, Luke, Betsy, and Benjamin, contributed to the motivation for doing this research study. Luke is a very active volunteer who came to the agency after the death of his daughter. Drowning in depression, he told me the invitation to come and help one day “saved my life.

Since then,” he told me proudly, “I’ve never missed a day. I would have died in my chair except for this place.” Betsy told me she came to the agency plagued by allergies, sickness and depression. After ten years she was healthy and the depression had disappeared. Betsy attributed her regained health to her new vegetarian diet coupled with increased compassion for others developed through her volunteer work. Benjamin signed up to volunteer against the wishes of his wife, because his doctor had told him not to overextend himself. After a few weeks of volunteering, Benjamin was feeling well enough to ride on the truck to pick up food from local grocery stores. Ten years later Benjamin voluntarily retired at 90 years old. The change in his life was phenomenal.

These stories seemed to confirm Jones’ (2006) hypothesis that those who remain involved in meaningful engagement for others are healthier. But I wondered, were these cases isolated random incidents, or representative of a larger group? So I decided to investigate this phenomenon further.

Shelving Seniors Hurts Everyone

Certainly if these stories were isolated incidents, this topic would have no relevance. However if they were an indication of a successful aging strategy, then this topic is very relevant to our society because the number of retired people in the United States is growing annually and the greatest growth is still to come (Gendell, 1998, p. 27). It is predicted that in 2011, ten thousand (10,000) Baby Boomers will turn 65 every day (Atchley, et al., 2009, p. 6) and the size of the 85+ population will have grown by 36% (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Thus it is no surprise that Vierck (Atchley, et al., 2009, p. 4) maintains that helping elders live healthier and happier lives will have a major impact on society, economics and public policy.

The government originally raised the retirement age to save money for the Social Security system, but this decision may have inadvertently contributed to improved senior health (Esteban, 2006, p. 3). Improved health for the elderly may help lower Medicare and/or Medicaid costs and lower the financial impact of private medical care for self-paying seniors. It would certainly be a boon to any proposed national health care changes. I believe we as a society have been willing to accept a way of life that encourages painful aging. I believe putting elders “on the shelf” hurts us all. Seniors lose out on lives of purpose, increased happiness and health, and we lose out on the benefits of their capable help coupled with their lifetime collections of wisdom and knowledge.

After listening to seniors tell how service impacted their lives, I realized that getting seniors engaged in meaningful community involvement may mean the difference between someone spending their final years of life shrouded with painful meaninglessness and a person finishing life crowned with personal fulfillment and happiness. Serving the community as a successful aging strategy deserves proper recognition. This research project adds substantial evidence to what is sometimes dismissed as incidental. Keeping seniors meaningfully engaged can improve quality and length of life for our elders (Greenfield & Marks, 2007, p. 13).

Dividends of Embracing Elderhood

Upon hearing the results of this study, a friend exclaimed, “Wow, I’m going to remember this for my retired parents who don’t know what to do with themselves.” I have found this study to be particularly relevant to those whose parents or other relatives are moving through elderhood. Families of older adults can use these results to increase health and happiness for their loved ones. Churches may strengthen or develop new elderhood programs based on these findings. Volunteer-based programs may cite the results of this study to leverage improvements for senior engagement opportunities. Communities may consider developing new initiatives based on providing meaningful service opportunities maintained and managed by seniors. Finally, individuals heading for retirement, me included, may use these findings to make plans for a rich and rewarding elderhood through meaningful community engagement.

So, do seniors agree that community involvement is good for them? I wanted to know what real, live older adults thought about staying involved, so I posed this research question: What does it mean for a senior to be engaged in community involvement? I also asked related sub-questions: Why do seniors choose to become involved in their communities? How is community engagement as a senior lived, experienced, articulated and felt? According to seniors, what impact does community engagement have on their health?

For this study, active community engagement was defined as being either a senior volunteer or senior employee of PACS. Respondents used the terms “working” and “volunteering” to describe paid or unpaid acts of service. “Involvement,” “engagement” and “community engagement” were used interchangeably to refer to service performed by the participants during their time spent at PACS. “Senior(s),” “elder(s)” and “older adult(s)” were used to denote anyone over the common retirement age of 65.

Views of Aging in Current Literature

Research supports the idea that those who remain engaged in society live healthier, more productive lives. Robert Putnam (2000) reports a myriad of studies that demonstrate the health benefits of staying socially engaged, such as lower heart attack rates, fewer colds, lower incidence of stroke, and lower blood pressure. Putnam found that those who are not previously involved but then join at least one group actually cut their “risk of dying over the next year in half” (p. 331). Many studies support Putnam’s claims by documenting various measurable health benefits to seniors through active volunteer engagement (Harris, 2005; Lum, 2005; Thoits & Hewitt, 2001; Windsor, Anstey, & Rodgers, 2008).

If you believe the many voices trying to lure active seniors into retirement communities, you might think that leisure, a warm place to stay, and three meals a day are the most important factors to provide optimum health for our seniors. But is this picture true? The research on the benefits of leisure in the process of aging is not conclusive. There is slightly positive evidence for men who had been engaged in recreational activities previous to retirement and for those participating in religious activities. However, engaging in other leisure activities, such as reading, gardening, going to a restaurant, and dancing, did not significantly improve the health of either men or women (Agahi, Ahacie, & Parker, 2006, Abstract; Greenfield & Marks, 2007, p. 9). What research does confirm is that staying active and participating in formal voluntary groups will bring greater quality and enjoyment of life (Esteban, 2006; Greenfield & Marks, 2007, p. 12).

Many of the studies on aging are done as statistical studies documenting effects of certain activities on selected health indicators. What is less often heard is the voice from those who are being studied. In searching the literature I found few articles which included quotes and stories from seniors, and often these were just used to set the stage for the study, not as reported research findings (Bradley, 2003). The current study seeks to provide such a voice to document how seniors themselves describe their experience.

Studying the Experience of Senior Community Engagement

The framework for this study is derived from continuity theory of normal aging, developed by Atchley in the 1980’s, which posits that as people age they endeavor to adjust to changes by maintaining existing internal and external structures (1989). Continuity theory of normal aging supports maintaining continuity in a person’s life as a strategy to promote successful aging (Agahi, et al., 2006). Therefore, according to this theory, as adults age they should be encouraged to remain active and meaningfully engaged, rather than being told to “take it easy.”

Research Design

To discover what seniors say about the experience of staying meaningfully engaged in their community after retirement, I used a research approach characterized by Creswell as phenomenology (2007, p. 58). The phenomenological method allows for interpreting the shared experiences of several individuals in an attempt to find the essence or shared meaning of the experience (Reisetter, Yexley, Bonds, Nikels, & McHenry, 2003).

Though I was once the supervisor of the study participants, at the time of this study I had not worked at Portland Adventist Community Services (PACS) for some time. Still, I worried that the participants might feel compelled to choose their words carefully in order to protect the relationships we had developed over the years. Therefore, the participants were encouraged to be completely honest, considering the legacy left behind through their responses.

To achieve validity in this study, I used three of the validation procedures advocated by Creswell (2007) and Seamon (2000): clarifying researcher bias, member checking, and rich, thick description. To clarify my bias, I must admit that my long history of working with senior volunteers has positively influenced me towards helping them remain meaningfully engaged in their community. To counteract this bias, I asked the respondents to give feedback to drafts of the research report. The changes they suggested were made. All participants seemed honored to be involved in the process. Also, to counteract my own biases,

I use extensive quotes, sometimes overlapping them to provide a rich experience for you, the reader. Extemporaneous details were often left in the accounts to give a better idea of the meanings the participants wanted to portray. I have tried to let the participants speak for themselves, using their own words as much as possible.

Appreciation and confirmation is given to our seniors when we listen to their complete stories. Hearing their realities helps us better understand the opportunity for other seniors to have richness in their lives when engaged in activity that is meaningful.

Who Participated in the Study?

Five seniors were chosen from 28 possible subjects to participate in this study. This sample size is consistent with recommendations (5-25 individuals) for phenomenological studies (Creswell, 2007, p. 61). These individuals were chosen because they matched the following criteria: (1) they worked or volunteered at PACS after retirement for at least five years; (2) they represented a wide base of experience within the agency, and (3) they worked at least four hours once a week. These criteria were chosen to demonstrate a strong, formalized commitment to community engagement after retirement and an understanding of the mission of the agency.

Alice, 77 years old, was a retired elementary school teacher who worked in the agency’s linen department eight hours each week. Betty and Rudy were a husband and wife team. Betty, 83 years old, was retired from a career of being the first woman to manage the parts department for a local John Deere tractor distributor. Rudy, 87 years old, was retired from a career as plant services manager for Tektronics, a high-tech industry. Both Betty and Rudy worked more than 20 hours a week at PACS for several years in about every capacity available. Iris, 80 years old, was retired from a career as an office assistant to high level government and private sector officers in Singapore. At the time of this study, she worked 35 hours a week at PACS providing telephone support and statistical record keeping. Russ, the fifth participant, retired from a career of courier service, drove a truck for PACS to pick up donated furniture 12 hours each week and had just celebrated his 90th birthday prior to this study.

What Were They Asked?

The interview questions, patterned after protocols suggested by Creswell (2007, p. 61), asked: What have you experienced through working at PACS? What situations have influenced or affected your experiences of working at PACS? Those two questions led to related questions until answers were exhausted.

So, What Did They Say?

The information collected from this study is presented in three parts: (1) a description of the environment of the agency and how the participants became involved with PACS, (2) information presented as rich, thick descriptions, followed by (3) a synthesis of the meanings found in these descriptions. The participants were not specifically asked about the work done and the environment of the agency, but their stories and responses provided much information about PACS along with reasons for becoming involved. We will look first at their motivation for volunteering at PACS and then listen to how the seniors described their work and the culture of their workplace.

Why They Volunteered

The most common reason given for coming to the agency was “not enough to do.” When asked for clarification, Iris, originally from Singapore, remarked, “Before coming to work [at PACS], you know, you get up and you just do what you want to do, but there’s nothing, no goals to accomplish. Nothing. Nothing to accomplish.” She added, “Well, it [life] was kind of empty because I left my home country and came here. I left all my friends behind. I made friends at church, but I needed to have more . . . to do something that I would enjoy.” Iris felt perplexed, explaining, “I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do at that time. I really wasn’t sure. I needed a job part time at least.”

But not everyone felt the need to add volunteering to their lives. Rudy commented, chuckling, “I didn’t want to go in there. I didn’t think that was very nice. I wasn’t impressed.” He then went on to explain how he finally got involved: “Well, I took my wife down; she wanted to go volunteer a couple of days. She went in and worked and I went in and looked around and then I waited out in the car for her. I took her down a couple times and stayed out in the car while she worked. As I was sitting out in the car I saw the people that were coming, the type of people and what they needed. It kind of worked on me a little bit and I thought, ‘Well, maybe there’s something I could do in there.’”

On the other hand, Betty, Rudy’s wife, came because “my friends were going; I thought it would be good.” She added, “We knew about volunteering at PACS. They always needed help, so that’s how we started.” Alice and Russ each indicated that they came because they longed to, as Alice put it, “be involved—to be of help to somebody.”

And so, each person signed on, albeit somewhat tentatively. Iris explained, “I heard they just give out food and that was it, but when I came here and I found what it was all about I was more than happy to come.” Alice was concerned about not fitting in, “I think I made it very clear that I’m not Adventist, so ‘if that’s an issue,’ I didn’t say that, but that was my intent. I soon, very soon, knew that that was not going to be an issue.”

Betty told about her first day, saying, “My hands got really dirty. I met my first street person and he shook my hand and gave me a big hug and I survived.” Her husband, Rudy, the reluctant joiner, laughingly recounted his experience after deciding to come in rather than sit in the car: “The first day Betsy said, ‘Luke will show you what to do,’ and Luke showed me how to dump garbage. I didn’t get much training.”

What They Found

Through describing their experiences, the participants painted a picture of the agency they had joined. Betty hinted at the complexity of the organization: “We didn’t know much about PACS before we started. We didn’t have a full understanding. That grew.”

Others commented on the services provided at the agency and types of jobs they did, such as “giving away clothing,” “sorting in the back,” and “I sit in the gift shop.” Rudy hinted at the history of the agency, commenting, “The best thing that ever happened was when the food program came out here [to this new location] because [at the old location] we had to go out by the bus stop and pick up everything all the time.”

Allusion was made to the agency as a faith-based organization when Betty explained, “We have worship in our worship room.” This was confirmed when Iris confided, “I have my own little corner where I always pray in the morning.”

Betty specifically referred to the nature of spontaneity and unpredictability of the daily routine. “We did so many things,” she said. “We had lots of things happen like when the car ran through the window and almost landed in the basement.” She went on to say she was very surprised one day when someone “cast a devil out of me—I got exorcised! The lady I was helping wanted a bunch of clothes for her family living in another country and I wouldn’t let her have them. So she told me I was devil-possessed and cast the devil out.” Rudy thoughtfully reflected, “You do things you never have done before.”

A different view of the organizational culture was provided as Iris confided, “You have been very caring and treated me not only as PACS staff, but as a friend. You treated me as an equal. You never talk down to me.” Rudy was more emphatic: “It’s a family.”

Servant Leadership Through Referent Power

Two overarching themes surfaced from the 90 significant statements gleaned from the interviews: personal fulfillment and personal wholeness. Before exploring the themes in more detail, it is important to note that references to connections with people were the background for nearly every story or reflection.

The Background Finding: Connected Again to People

Every person mentioned making new friends. For brevity, some of the comments are recorded here. Rudy said, “We made lots of friends when we worked at PACS.” Both Betty and Rudy commented, “We’ve met so many people. We had daily visitors there.” They went on to explain, “When we started the store we met a lot of people in the neighborhood. They even brought us dinner at night.” They described friendships outside of their normal comfort zones: “Gunboat came in in the morning to see what we had and then ‘pick it up at noon,’ he said. Then he’d come in drunk and take it home with him every single day. From nine ‘til noon he was weaving down the road. But he never asked for food. He never asked for anything, nothing. He’d visit with us and tell us about his naval experiences and stuff like that.”

Rudy added, “At this time and age I like a place where I can meet people.” “There were so many people we’ll never forget,” concluded Betty. “They were very nice.” Iris explained, “I liked meeting people. I really enjoy it here because I get to meet people, make new friends.” Alice agreed, saying, “I find a lot of joy and satisfaction dealing and communicating with people and making new friends.”

Some commented on deepening relationships with fellow volunteers. “I feel very, very happy right now because PACS is like an extended family to me,” said Iris. “It’s like they are related to me, they are so close.” Rudy summed up the comments from several of the participants

when he stated, “PACS feels like home. I always feel like I’m at home there.” Alice related a story: “My supervisor said, ‘I think you and somebody named Joyce would really like to work with each other.’ And that was how I met Joyce. That was just a grand experience.” She then philosophized: “I think that staying around people and dealing with people and situations is stimulating. It makes good mental health and that affects your physical health. So I think it’s a good thing. I think the longer I can stay active the better off I am. I just think it’s really good.

I know it’s been good for me.”

Dominant Theme 1: Personal Fulfillment

The first theme to surface, personal fulfillment, emerged as a theme with several categories. First, a strong sense of personal satisfaction ran through the participants’ descriptions of their experience at PACS. All of the participants expressed pride in their work, but Iris summarized it by stating succinctly, “I’m very proud of what I do. I find it very satisfying.” Second, participants expressed a definite sense of belonging. Iris stated happily, “It’s the most wonderful experience in my whole life because I work with so many wonderful people.” Russ said simply, “The meaning to me is family.” This was echoed by Rudy and Betty: “I felt part of the family. There were people to back us up.” And Rudy added, “We feel safe here, needed.”

Working as part a team to help others was also highly ranked. Betty stated, “It means family and people caring about each other. There is genuine caring and love all around. We are always trying to help somebody.” Others echoed a sense of fulfillment and reward. Russ, the 90- year-old truck driver, spoke for all of them when he stated, “It’s the most rewarding thing to do when you know you’re doing something for someone else and you’re not expecting anything in return.” He related the following incident:

One Sunday we went down to a two-bedroom house and we went in and they had a wooden spool for a kitchen table, a few dishes in some apple boxes for a cupboard, a pile of clothes and no beds. We took them a nice breakfast set, Davenaux, reclinerike chair, end tables, and a full- sized bed. We were setting up the bed. There were three kids, a boy about seven and two girls, about four and eleven. I said, ‘Where do you want the bed?’ The mother said, ‘Put it in this bedroom here.’ The oldest girl said, ‘Mister, is that really going to be my bed? I never ever had a bed.’ Can you figure that, ten or eleven years old and never had a bed? Can you imagine what that does to your heart?

Betty explained, “I feel I’m doing something to help somebody and that makes me feel good. It helps both of you, those that serve and those that are served.” Taking a more philosophical view, Rudy elaborated, “I’m working for the Lord. I can’t preach, teach or give Bible studies, but I can do this kind of work.”

All participants expressed a sense of personal accomplishment in the ways they chose to cope with challenges they encountered at PACS. The challenges were many and varied, from working with clients and working with each other to developing new programs and learning how to use new equipment.

Working with people was the challenge most often identified. “Sometimes when you take care of the phones you get people getting upset with you . . . and that’s when you got to keep your cool,” said Iris. “I always think of that, you know. The poor people are depressed so that’s why they talk like that.” She further explained, “It’s a challenge that I know I can overcome because I have the Lord on my side. I don’t get angry with them because I do feel sorry they are in a bad situation. I always say that it could be me that’s the difficult one, not they.”

Betty said, “It was a good experience dealing with the people—sick people who were needy—people who were our age. That’s what you run into.”

“I think the only challenge [for me] was dealing with other volunteers,” commented Alice. “Take Sarah as a case in point. I took it on as a challenge, ‘You must get along with this lady. . . .’ And we did. We’re good friends now.”

Betty and Rudy admit to another challenge: “Opening up a store when you didn’t know anything about it. That was quite interesting.” A related difficulty was working through the details of setting up the new store. “My wife wanted it this way” said Rudy, “and the executive director thought it would be better that way and then I wanted it this way. It felt good to accomplish something.”

Using new equipment was also cited as a challenge, but each person dealt with it differently. “I’d never done the cash register, ever in my life,” said Iris. “It was a big challenge. That was something I was really afraid of. I was put on as ‘in training’ for one month. That helped. After one month the executive director pulled off the words ‘in training’ and said, ‘You’re here.’ And I’ve enjoyed it ever since.” In elaborating on that experience, Iris related the only concern about age discrimination that surfaced in all the interviews: “I was wondering at this age, after retirement, ‘Am I going to be able to grasp it [the cash register]?’ If I was young I don’t think I would have been nervous, but now I didn’t want to be a failure. I didn’t want this in the latter years of my life to be a failure and I’m glad I did it. I conquered that.”

Rudy approached new equipment much more pragmatically, as the following interview excerpt demonstrates:

“I had an experience with driving a lift truck,” said Rudy.

“You said you already knew how to do that,” said the interviewer. “Well I did, kinda,” said Rudy, shifting in his chair. “I wasn’t a professional.”

Russ took a more confident approach to using the equipment: “There hasn’t been anything I couldn’t do.”

Dominant Theme 2: Personal Wholeness

The second theme, that of experiencing personal wholeness, surfaced in several ways during a discussion of aspects of physical and emotional health and the relationship of the participants’ work to their spiritual health.

When asked how working at the agency had impacted them, the participants tended to equate physical health with mental or emotional health. “It makes me feel better physically and mentally,” said Betty. “You don’t have time to think of yourself so much, so you are healthier.” Alice observed that “it makes good mental health and that affects your physical health.” Iris described it this way: “I felt better after I volunteered because every morning I look forward to coming here and doing what I love. I have goals. I’m very happy here. I had no idea I would end up this way. I am so happy. The greatest blessing of my life is working at PACS.”

Russ proudly explained his recipe for good health, “Just like my doc told me when I was 42, ‘You quit smoking—that’s good. Always stay active. The biggest share of my men patients, if they sit and watch TV, I go to their funerals. The ones who stay active live until their 80s and 90s.’ I can still do anything I did when I was 30 or 40 years old and I’m 90.”

Interestingly, the participants had an easier time describing the impact of working at the agency on their spiritual lives, though they seldom mentioned God directly. All felt that the experience had enhanced their spiritual growth, often in deep ways. Betty, for instance, related the following breakthrough story: “This gentleman came and he was so dirty and smelly and he had been drinking, as a lot of the people down in that area do. It wasn’t a real good area. I gave him something and he was so happy and he threw his arms around me and hugged me with those dirty little hands of his. I shall never forget it, but I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, this is terrible.’ But I didn’t wash my hands. I didn’t fall off or anything and I think that was perhaps the first day that I realized that I wasn’t rich but I had a lot more than a lot of other people. I didn’t ever realize that people were that needy. I never did. And I’ve blessed that man ever since.”

Rudy talked about his own spiritual response to serving destitute people. “It makes you see how other people have to do without food and how they get help…. After we were there a little while it kind of grows on you and you see the need and we really enjoyed it.” He described a gradual change of heart, “I really didn’t have much feeling about people. I just saw people come and go, get food, you know. But after I found out some of the problems they were having and some of the needs—it helps you.” He went on to relate a later experience that was not so positive, explaining how he had been helping a woman choose the proper amount of food. “She just hollered out real loud, ‘You don’t have a heart!’ I kind of felt bad about that.”

Religious duty was cited by Alice as part of the impact on her personal life. “I think it’s a growing experience,” she said. “I know that the bulk of our people are needy and if I can serve and help them, I think that’s what our religion is all about. That’s what [Jesus] would want us to do—help others.”

Betty philosophized in the same vein: “The Lord does use you, yes. You have the poor with you always, so you should be taking care of them, doing what you can. You pray for them at night.” Russ stated simply: “I feel closer to the Lord,” and Rudy added, “Spiritually, it’s lifted me up.” Iris agreed: “I’m enriching my spiritual life by talking with people and listening, and people who come here seem to be so appreciative.”

Alice described the experience of being a Presbyterian working in a Seventh-day Adventist agency: “It expands your horizons. The very fact that I’m in an atmosphere that is different theologically from mine, and I feel perfectly comfortable, and I think it’s a good thing to know about how other people worship.”

Fulfillment in Service to Others

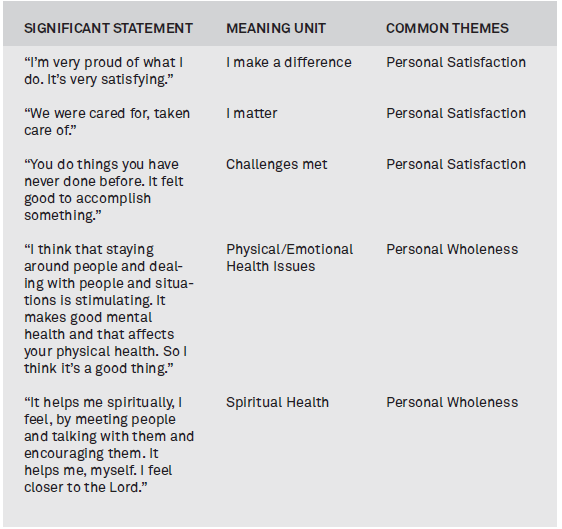

When these seniors stayed actively involved in their community by working together to touch the lives of those who needed their care, they experienced happiness and a sense of purpose. It was about remaining important for someone and important to someone. Table 1 contains a sample of significant statements with corresponding meaning units and the common themes that were derived.

Table 1: Sample Data Analysis

Summing It All Up

In this study, five seniors who are actively engaged in serving their community described the experience of working at a social service agency and the impact that experience had on them personally. The most widely identified benefit was the opportunity to remain actively engaged with people. Though boredom was most often cited as the motivation for service, participants described a high degree of personal fulfillment through indicators such as intense personal satisfaction, a sense of belonging, helping others, and meeting challenges successfully. They also reported personal wholeness through a sense of general well-being, in addition to a wide variety of spiritual benefits.

Additional studies from other agencies would add to or clarify these findings. It might be beneficial to include additional types of data, such as questionnaires or focus groups to enhance wider discussion and prompt recollection. This study pointed out a discrepancy between the reasons seniors decide to volunteer and the recruiting points often used in recruiting volunteers. More in-depth study of this subject would assist the development of more effective recruitment strategies.

Helping Seniors Lead

When I embarked on this study, I expected that the research evidence explored in the literature survey would be confirmed by the participants. I expected them to verbalize and verify the quantitative research by making such statements as, “I’m not sick as much,” “my blood pressure is better,” or “I don’t struggle with cholesterol anymore.” I suspected that statistics proving better health would be related as a strong motivating factor for seniors to become involved.

Surprisingly, the seniors never mentioned measurable health indicators as a reason to join, or as a benefit they experienced through their service. Perhaps those statistics were such common knowledge to the participants that they did not think to mention them. In any case, there was no indication that they expected or experienced measurable health benefits from their engagement with the agency.

I also discovered that our best intentions of protecting elders because of their diminishing physical capabilities may remove from them a great source of personal fulfillment, namely that of allowing them opportunities to meet challenges successfully. The participants displayed a great deal of resiliency and creativity when meeting challenges in a supportive environment.

William Pagonis (2001) states that “leaders are not only shaped by the environment, they also take active roles in remaking that environment in productive ways” (p. 96). By this definition, the participants in this study are clearly leaders.

Allowing our seniors opportunities to stay involved is in accordance with the continuity theory of aging and what the seniors described in this study. Continuity theory suggests that continued involvement with formal voluntary groups can enhance well-being and successful aging above and beyond involvement in leisure activities alone (Atchley, 1989). The responses of the participants confirmed that working together to help others was a large part of their happiness.

Charities, caregivers, congregations, retirement centers, volunteer managers, and health insurance companies would do well to heed the voices of these seniors. Supplementing marketing efforts that target leisure living with opportunities for meaningful community engagement would offer elders a more complete strategy for successful aging.

I will take note of the comments of these seniors and adjust my future recruitment methods and recommendations to include, along with statistical information, a greater emphasis on the less tangible rewards identified in this study. Also, I will never again feel apologetic for asking older adults for help. May we never take from our seniors the joys of making new friends, increased happiness, and a sense of purpose. These are laudable pursuits for anyone, ones that are especially achievable in the golden years of life.

A Final Thought

Through the years I have learned that working with seniors can bring much happiness. I am deeply touched as I see elders continue to lead through living lives of commitment to others. Their eyes brighten, their steps lighten, and their faces glow as they regain a sense of purpose and fulfillment through performing meaningful service to their communities. This is overshadowed, however, by the ache in my heart as I observe the process of aging take its toll. None of us is immortal.

Even so, through their selfless giving, older adults continue to lead, and receive happiness and personal fulfillment from that leadership. The elders who participated in this study made a significant impact on their community. And they still give.

In describing the characteristics of a leader of influence, Maxwell and Dornan (1997) assert that “if your life in any way connects with other people, you are an influencer” (p. 3). By participating in this study, these five seniors freely opened their hearts in a way that will continue to influence society in the years to come. The legacy they leave through their brave leadership is immeasurable.

None of these seniors came to PACS to be leaders. They only wanted to serve. They did not know, nor did they particularly care, about theories of leadership. When I gave a brief description of servant-leadership to Iris, she listened condescendingly to my lofty jargon, shrugged her shoulders then changed the subject. These seniors naturally exhibit listening skills and empathy. They experience healing, engage in persuasion, and develop foresight and awareness. They acts as stewards, and are very focused on making sure everyone in the team is able to give their best. They also rejoice when they are able to help others. Some of them really get involved in seeing beyond the daily realities of the operation to dreaming how the agency could improve and contribute to building their community. All these qualities are characteristics found in servant-leaders as identified by Larry Spears (2004), chief executive officer of the Greenleaf Center for Servant-Leadership. Though their leadership is often unintentional, they live to bless others.

And that blessing is reciprocal. As Rudy confided, “When you retire and get old, all your friends are dead. When you are working at PACS, you make new friends and your life is full again.”

References

- Agahi, N., Ahacie, K., & Parker, M. G. (2006). Continuity of leisure participation from middle age to old age. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, S340-S346.

- Atchley, R. C. (1989). A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 29(2), 183- 190.

- Atchley, R. C., Baxter, S. L., Blanchard, J., Brady, K., Comfort, W. E., Egbert, A. B., et al. (2009). Working with seniors: Health, financial and social issues. Denver, CO: Society of Certified Senior Advisors.

- Bradley, D. B. (2003). A reason to rise each morning: The meaning of volunteering in the lives of older adults. Generations, 23(4), 45-50.

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Esteban, C. (2006). Does working longer make people healthier and happier? Trustees of Boston College, Center for Retirement Research. Work Opportunities for Older Americans (Series 2, February 2006). Retrieved May 21, 2009, from http://mpra.ub.uni- muenchen.de/5606/

- French, J. R. P., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright & A. Zander (Eds.), Group dynamics (3rd ed., pp. 259-269). New York: Harper & Row.

- Gendell, M. (1998). Trends in retirement age in four countries, 1965-95. Monthly Labor Review, 121(8), 20-30. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1998/08/art2full.pdf

- Greenfield, E., & Marks, N. F. (2007). Continuous participation in voluntary groups as a protective factor for the psychological well-being of adults who develop functional limitations: Evidence from the National Survey of Families and Households. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(1), S60-S68.

- Harris, A. H. S. (2005). Volunteering is associated with delayed mortality in older people: Analysis of the longitudinal study of aging. Journal of Health Psychology, 10(6), 739- 752.

- Jones, T. (2006). Elder: A spiritual alternative to being elderly. Portland, OR: Elderhood Institute Books.

- Lum, T. Y. (2005). The effects of volunteering on the physical and mental health of older people. Research on Aging, 27(1), 31-55.

- Maxwell, J. C., & Dornan, J. (1997). Becoming a person of influence: How to positively impact the lives of others. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

- Pagonis, W. G. (2001). Leadership in a combat zone. Harvard Business Review, 79(11), 107-15.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Reisetter, M., Yexley, M., Bonds, D., Nikels, H., & McHenry, W. (2003). Shifting paradigms and mapping the process: Graduate students respond to qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 8(3), 462-480. Retrieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR8- 3/reisetter.pdf

- Seamon, D. (2000). A way of seeing people and place: Phenomenology in environment- behavior research. In S. Wapner, J. Demick, T. Yamamoto, & H. Minami (Eds.), Theoretical perspectives in enviroment-behavior research (pp. 157-178). New York: Plenum.

- Spears, L. C. (2004). Practicing Servant-Leadership. Leader to Leader, 34 (Fall), 7-11.

- Thoits, P. A., & Hewitt, L. N. (2001). Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(June), 115-131.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). A profile of older Americans: 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2009, from http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/Profile/index.aspx

- Vierck, E. (1988). Older is better: Common-sense steps to a long life, health, and happiness. Washington, DC: Acropolis Books.

- Windsor, T. D., Anstey, K. J., & Rodgers, B. (2008). Volunteering and psychological well- being among young-old adults: How much is too much? The Gerontologist, 48, 59-70.

- Yukl, G. (2006). Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Rhonda Louise Whitney is Community Outreach Director for the Oregon Conference of Seventh-Day-Adventists in Portland, Oregon.