Abstract: Both the emotion and expression of gratitude produce benefits for the person who is thankful, as well as the person being thanked. This study explores the degree to which various forms of gratitude expression are appreciated by those being thanked. In a survey-based study (N=361), costly, private expressions of gratitude were more appreciated by people being thanked than less costly, public expressions. Higher levels of the HEXACO personality traits of conscientiousness and emotionality increased the degree to which people appreciated being thanked. Lower honesty-humility (e.g., narcissism) predicted a greater appreciation of receiving public expressions of gratitude while higher honesty-humility predicted a greater appreciation of receiving private expressions of gratitude. This information can be used by Christian leaders to help equip others for ministry.

Keywords: gratitude; appreciation; conscientiousness; emotionality; honesty-humility

Cicero (106–43 BC) writes, “Gratitude is not only the greatest of virtues, but the parent of all others.” While the biblical writers might not completely agree with this statement, the Apostle Paul’s frequent expression of gratitude for the people to whom he wrote would undoubtedly be appreciated by Cicero. Paul expresses gratitude to God for the Romans (1:8), the Corinthians (1 Cor. 1:4), the Ephesians (1:6), the Philippians (1:3), the Colossians (1:3), the Thessalonians (1 Thess. 1:2, 2 Thess. 1:3), Timothy (2 Tim. 1:3), Titus (2 Cor. 8:16–17), and Philemon (1:4). Although most biblical authors do not express gratitude to the audience whom they were addressing, this Pauline idiosyncrasy can serve as a model for today’s Christian leaders. This study presents an overview of what we know from psychological research concerning gratitude and gratitude expression, and also presents new research examining the effectiveness of various forms of gratitude (public, in a small group, written, and in private), both in general and in light of the personality of the person being thanked.

Gratitude and the Christian Leader

Among the responsibilities given to Christian leaders in the Scriptures are the pastoral duties of prayer (Acts 6:2–3), teaching the Word (Acts 6:2–3, 1 Tim 5:17, Titus 1:9), caring for the Christian community (1 Pet. 5:2–3, 1 Tim. 3:5, Heb. 13:17), and equipping church members for ministry and building up the body of Christ (Eph. 4:11–13). Gratitude expression is perhaps most relevant to the last duty—that is, equipping Christ followers for what Christ has called them to do. From the perspective of organizational psychology, εἰς ἔργον διακονίας, “for the work of ministry” (Eph. 4:12, NIV) can be considered performance, or accomplishing the tasks for which one is responsible in an organizational context, such as a church.

A classic conceptual formula (Anderson & Butzin, 1974; Heider, 1958) for modeling performance is:

Performance = Motivation × Ability

This indicates “the work of ministry” that a Christian performs can be roughly described as the product of his/her motivation to do ministry and his/her ability to do the ministry. If either the motivation or ability is absent, the ministry will not be carried out. The greater the motivation and the greater the ability, the more ministry will be accomplished. Motivation is a psychological phenomenon within an individual which depends on the individual’s personality traits, the beliefs the individual has about the ministry (such as the value of the likely outcomes), and the social context (Maslow, 1943; Vroom, 1964; Weiner, 1985). Ability is a characteristic of the individual that depends on the individual’s specific capacities (similar to some interpretations of spiritual gifts) and the opportunities to use one’s gifts or abilities in a specific context (Blumberg & Pringle, 1982; Sternberg & Kaufman, 1998).

This model implies that to equip another Christian for the work of ministry, Christian leaders should seek to increase both a Christian’s motivation and ability to perform the ministry. Expressing gratitude is one means by which a Christian leader can do so. For example, if a person has participated in a ministry for the first time, such as tutoring neighborhood children, and has received thanks for it, especially from someone with status in the church, the person may be more motivated to perform the ministry again.1 Similarly, a new Christian who hears a pastor thank the team which carried out a Vacation Bible School will learn of the opportunity to serve the Lord in this way, increasing his/her ability (and motivation) to join this ministry the following year.

Benefits Associated with the Emotion of Gratitude

Gratitude can be defined as “the positive emotion one feels when another person has intentionally given, or attempted to give, one something of value” (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006, p. 319). Among other functions, emotions prepare a person for specific actions (Frijda, Kuipers, & Ter Schure, 1989; Schwarz & Clore, 1996). For example, anger prepares a person to fight or argue, while fear prepares a person to flee or avoid. The emotion of gratitude prepares a person (the beneficiary) to respond favorably to a person (the benefactor) who has provided a benefit to the beneficiary (Algoe, Haidt, & Gable, 2008; Ritzenhöfer, Brosi, Spörrle, & Welpe, 2019).

Gratitude is often considered a moral emotion because it motivates people in ways that affect others’ well-being (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006; Haidt, 2003). When leaders experience gratitude, they are more likely to treat all people more fairly and with greater respect (Ritzenhöfer et al., 2019). Gratitude also generates a “moral memory,” causing us to feel indebted to the benefactor until we respond (McCullough, Kilpatrick, Emmons, & Larson, 2001; Simmel, 1950, p. 338); for benefits that we cannot equitably reciprocate (e.g., to parents and God), gratitude may create a permanent sense of attachment and obligation.2

The benefits of experiencing the emotion of gratitude, even when it is not expressed to others, include enhanced physical health (McCullough & Emmons, 2003), the acceptance and reframing of negative situations (Lambert, Graham, Fincham, & Stillman, 2009), and increased life satisfaction (Lambert, Fincham, Stillman, & Dean, 2009). Because gratitude creates a sense of indebtedness, reciprocating beneficial behaviors becomes more frequent in relationships where gratitude is expressed (Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006; Ritzenhöfer et al., 2019), including leader-follower relationships (Michie & Gooty, 2005). Not only does the person expressing gratitude want to treat the person being thanked better, but his or her evaluation of the person being thanked increases (Algoe et al., 2008). Positive emotions, including gratitude, signal that an environment is safe and, consequently, new solutions to problems and new interpretations of information can be considered with an open mind, a phenomenon known as “broaden and build” (Fredrickson, 2001; Fredrickson & Joiner, 2005).

All these phenomena and processes associated with gratitude, when experienced habitually, work together to create trusting and strengthened relationships between the person experiencing gratitude and the person being thanked. This sets the stage for greater cooperation and goal achievement in personal relationships and in organizations, such as churches (Algoe et al., 2008; Bartlett & DeSteno, 2006; Lambert, Clark, Durtschi, Fincham, & Graham, 2010).

Benefits Associated with Gratitude Expression

The focus of this study is not on experiencing the emotion of gratitude, but on gratitude expression, communicating one’s gratitude to the person for whom one is thankful, typically orally (such as publicly in a meeting or privately with the person) or in writing (such as through a note or, in the case of the Apostle Paul, an extensive letter).

Many of the benefits associated with gratitude expression are described in the “find, remind, and bind” theory of gratitude expression (Algoe, 2012; Algoe & Zhaoyang, 2016; Lambert et al., 2010). Three important functions of gratitude expression are to help us find like-minded people who are willing to form a relationship with us and to cooperate in some way (find), to remind us of who is willing to cooperate with us (remind), and to demonstrate that a continued cooperative relationship is likely (bind). Thus, there are benefits both for the person expressing gratitude and for the person who is being thanked.

For Christian leaders, there are additional benefits associated with gratitude expression. When people in organizations have leaders who express gratitude, they view their leaders as more warm and caring (Ritzenhöfer et al., 2019; Williams & Bartlett, 2015) and thus more responsive to the followers’ efforts (Algoe, Fredrickson, & Gable, 2013; Algoe et al., 2008). Such leaders cause people to feel more satisfied with the organization, less willing to leave, and more willing to cooperate with the leaders (Williams & Bartlett, 2015). In addition, when a leader expresses gratitude, the person being thanked is more likely to repeat doing whatever generated the gratitude (McCullough et al., 2001). They are even likely to work harder because they feel valued and appreciated (Grant & Gino, 2010). The degree to which people will be motivated to continue or increase their work depends on their personality; those who seek social integration and develop new relationships seem the most responsive (Deutsch & Lamberti, 1986). However, Christian leaders must be careful not to exploit this tendency in people by using insincere gratitude expressions or flattery (Wood et al., 2016).

The benefactor, the person being thanked, also benefits from a Christian leader’s expression of gratitude. Those being thanked receive evidence that their efforts are valued and worthy of approbation by someone with expertise (Ritzenhöfer et al., 2019). Receiving an expression of gratitude also indicates that a Christian leader is likely to reciprocate and provide what is needed for the person who is thanked (Algoe et al., 2008). The person being thanked also receives information that the Christian leader is not selfish and is willing to share the credit for something, a sign of trustworthiness and humility (Ritzenhöfer et al., 2019). It also signals that the Christian leader trusts and views the person being thanked positively, indicating that a continued relationship is likely and desired by the Christian leader. This phenomenon is especially strong when Christian leaders communicate they appreciate the person being thanked and not just the act the person performed (Algoe, Kurtz, & Hilaire, 2016).

In addition, third-party observers of gratitude expression also are influenced positively when they see a Christian leader thank someone. It signals information about the leaders’ character and values, as well as with whom the leader is motivated to cooperate (Ritzenhöfer et al., 2019). The witnessing effect occurs when a group member observes an emotional exchange between other members of the group (e.g., gratitude expression) and adjusts his or her behavior to make the group more functional (Algoe, Dwyer, Younge, & Oveis, 2019). For example, when a person observes a pastor thanking a church member, the person is more motivated to respond to requests for help from the pastor because the pastor is likely to value and reward such efforts. Similarly, the person’s opinion of the church member being thanked goes up because the pastor has communicated that the church member has successfully contributed to something valued by the church.

Research Question

Because there are so many potential benefits from Christian leaders expressing gratitude to others, this study seeks to understand what form of gratitude expression (e.g., public, in a small group setting, through a written note, or private) is most appreciated by people. The first exploratory hypothesis is thus:

Hypothesis 1: Some forms of gratitude expression will be appreciated by people more than others. Because people differ in patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, personality traits will likely influence the degree to which people appreciate different forms of gratitude expression (Deutsch & Lamberti, 1986; Dunaetz, Lisk, & Shin, 2015).

To better understand the effects of personality on the appreciation of various forms of gratitude expression, the second exploratory hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2: Some personality traits will predict appreciation for each of the forms of gratitude expression studied. Understanding which forms of gratitude expression are most appreciated and by whom should enable Christian leaders to more effectively equip members of their communities “for the work of ministry” (Eph. 4:12, NIV).

Method

To test these hypotheses, an online survey was used to collect data from a broad audience, since most church leaders are interested in reaching a wide range of people. Recruited participants provided information about the degree to which they appreciated being thanked via various forms of gratitude expression, as well as information measuring personality traits and demographic information.

Participants

Participants were recruited through the second author’s social networks, and then through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an Internet-based crowdsourcing marketplace where requesters post tasks for workers to complete in exchange for compensation. MTurk workers are more demographically diverse than most convenience samples, and the data they provide is at least as reliable as data collected using traditional methods (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011). For completing this survey, 319 MTurk workers received $1.00 each. A total of 361 participants provided usable data. The median ages were between 25 and 34 years, and 54% of the participants were male.

Measures

Appreciation of Forms of Gratitude Expression

The participants indicated how strongly they would agree with statements concerning feeling appreciated at work via four forms of gratitude expression: public recognition, recognition in a team setting, written communication, and private recognition. They indicated on a five-point Likert scale how appreciated they would feel if it came from a supervisor, from a colleague, and from a new hire for each form of gratitude expression. There were twelve items (four forms of gratitude expression by three sources). Survey items included, “I would feel very appreciated if my supervisor gave me public recognition, such as at a large awards ceremony,” and “I would feel very appreciated if my colleague thanked me through a sincere email, text, handwritten note, or other means of written communication.” For each participant, appreciation: public thanking, appreciation: group thanking, appreciation: written thanking, and appreciation: private thanking were calculated by averaging the responses on the three relevant items.

Personality Traits

HEXACO (Ashton & Lee, 2007; Lee & Ashton, 2005) is a model of personality measuring six factors, each comprising a set of traits, at least one of which is correlated to most, if not all, other personality traits. Participants responded to 60 Likert statements from the HEXACO-PI-R self-report form (Ashton & Lee, 2009).

Honesty-Humility. People high in honesty-humility are honest, sincere, faithful, and modest. People low in this trait tend to be arrogant, dishonest, materialistic, narcissistic, and immoral (Lee & Ashton, 2005; Lee et al., 2013). Sample items include, “I think I am entitled to more respect than the average person is” (reverse-scored), and “I want people to know that I am an important person of high status” (reverse-scored).

Emotionality. Emotionality refers to the degree to which a person is fearful, anxious, and dependent. Individuals high in emotionality are highly anxious, worry obsessively, and have emotional attachments. Individuals low in emotionality tend to be indifferent to family ties and expose themselves to physical risk (Ashton & Lee, 2009; Ashton, Lee, & De Vries, 2014). Sample items include, “I would feel afraid if I had to travel in bad weather conditions,” and “I remain unemotional even in situations where most people get very sentimental” (reverse scored).

Extraversion. Extraversion measures an individual’s tendency to engage in social interactions, express positive emotions, and develop a wide range of friends (Lee & Ashton, 2004). Sample items measuring extraversion are, “I feel that I am an unpopular person” (reverse scored), and “In social situations, I’m usually the one who makes the first move.”

Agreeableness. Agreeableness measures the degree to which an individual is patient, tolerant, and peaceful (Ashton et al., 2014). Items which measure agreeableness include, “I rarely hold a grudge, even against people who have badly wronged me,” and “My attitude toward people who have treated me badly is ‘forgive and forget.’”

Conscientiousness. Conscientiousness measures the degree to which a person is organized, self-disciplined, hardworking, and efficient (Lee & Ashton, 2004). Items measuring conscientiousness include, “I often push myself very hard when trying to achieve a goal,” and “I do only the minimum amount of work needed to get by” (reverse scored).

Openness. Openness (or openness to experience) measures how much a person is inquisitive, innovative, imaginative, and creative (Lee & Ashton, 2004). Items measuring openness include, “People have often told me that I have a good imagination,” and “I don’t think of myself as the artistic or creative type” (reverse scored).

Demographics

Age and sex were both measured with one item. Participants indicated their age by choosing one of seven ordinal categories, 1 = “18–25 years” to 7 = “75 or older.” For sex, participants could choose between male, female, and “other/ prefer not to state.” The third choice was considered missing data.

Results

The means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the variables measured are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations, Correlations, and Reliability Coefficients of All Measures

| MEASURE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Personality Traits | ||||||||||||

| 1. Honesty-Humility | (.81) | |||||||||||

| 2. Emotionality | -.11* | (.77) | ||||||||||

| 3. Extroversion | .10 | -.19*** | (.83) | |||||||||

| 4. Agreeableness | .28*** | -.13* | .32*** | (.81) | ||||||||

| 5. Conscientiousness | .22*** | .06 | .26*** | .12* | (.81) | |||||||

| 6. Openness | .11* | -.03 | .07 | .13* | .14** | (.79) | ||||||

| Appreciation | ||||||||||||

| 7. Public Thanking | – 27*** | .12* | .08 | -.01 | .13* | .02 | (.90) | |||||

| 8. Group Thanking | -.14** | .13* | .15** | .04 | .24*** | .11* | .69*** | (.84) | ||||

| 9. Written Thanking | .20*** | .15** | .13* | .15** | .29*** | .17** | .11* | .26*** | (.81) | |||

| 10. Private Thanking | .26*** | .13* | .12* | .17** | .32*** | .25*** | .09 | .27*** | .74*** | (.81) | ||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| 11. Age | .27*** | -.03 | .19*** | .15** | .22*** | .16** | .05 | .06 | .16** | .15** | — | |

| 12. Gender | .11* | .37*** | -.02 | -.04 | .13* | .01 | -.04 | .03 | .17** | .10 | .12* | — |

| Mean | 3.47 | 3.14 | 3.22 | 3.28 | 3.88 | 3.64 | 3.49 | 3.89 | 4.08 | 4.21 | ||

| Standard Deviation | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.69 | 1.09 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.64 |

Different Levels of Appreciation of the Forms of Gratitude Expression

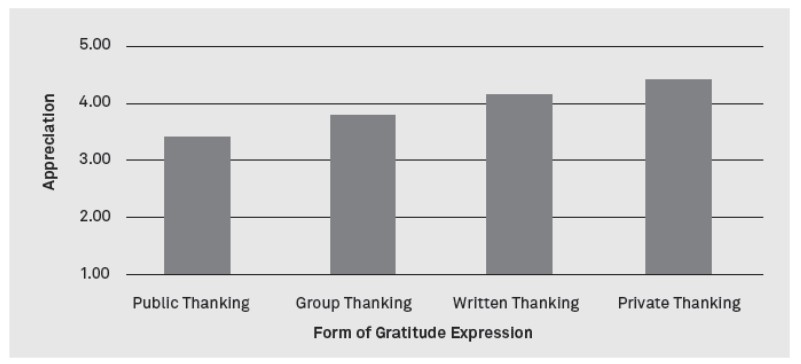

The first hypothesis predicted there would be different levels of appreciation of the four forms of gratitude expression: public, group, written, and private. The difference of the four means was tested with a repeated measures one-way ANOVA. This difference was significant, F(3,180) = 75.12, p < .001. Private thanking was the most appreciated, followed by written thanking, small group thanking, and finally by public thanking. Post-hoc pair-wise comparisons indicated that the differences of appreciation between all four forms were significant, all ts(360) > 3.77, all ps < .001 (two tails), all ds ≥ .18. The means presented in Table 1 are represented graphically in Figure 1.

Figure1

Appreciation of the Four Forms of Gratitude Expression

Personality Traits as Predictors of Appreciation of the Forms of Gratitude Expression

The second hypothesis was that some HEXACO personality traits would predict the degree to which each of the forms of gratitude expression was appreciated. A multiple regression analysis modeling the appreciation of each form of gratitude expression fully supported this hypothesis (Table 2). Multiple regression is a form of analysis that helps find the variables that predict the phenomenon being modeled while considering the overlap in variation with other variables. Since most of the variables in the study are significantly correlated with each other (Table1), multiple regression mathematically removes the over lap of the personality variables to determine which ones predict the appreciation of each of the forms of gratitude expression.

Table2

Standardized Coefficients Predicting Appreciation of Gratitude Expression from Personality Traits

Fonn of Gratitude Expression

| Personality Trait | Public Thankln1 | Group Thankln1 | Written Thankln1 | Private Thankln1 |

| Honesty-Humility | -.32* ** | -. 21*** | .13* | .18* ** |

| Emotionality | .09 | .13* | .18* * | .16* * |

| Extraversion | .07 | .12* | .06 | .04 |

| Agreeableness | .05 | .04 | .07 | .08 |

| Conscientiousness | .17** * | .22* * | . 21*** | . 23* ** |

| Openness | .02 | .09 | .12* | .19* ** |

| Total R2 | .12* ** | .13* ** | .16* ** | . 20* ** |

The results show that greater appreciation of public thanking is predicted by lower honesty-humility and higher conscientiousness. Greater appreciation of group thanking is predicted by lower honesty-humility, higher emotionality, higher extraversion, and higher conscientiousness. Greater appreciation of both written thanking and private thanking is predicted by higher honesty-humility, higher emotionality, higher conscientiousness, and higher openness.

Additional analyses, which repeated the above analyses while controlling for gender and age, indicate that the same significant relationships emerged for all forms of gratitude expression; gender and age were not significant predictors for any of them.

Discussion and Application

This study has demonstrated that people appreciate various forms of gratitude expressions differently. Private, individual expressions of gratitude are appreciated the most, followed by written expressions of gratitude, expressions of gratitude in team or small group settings, and, finally, expressions of gratitude in public or large group settings. Furthermore, the degree to which a person appreciates each form of gratitude expression depends on his or her personality. Conscientiousness and honesty-humility have the greatest influence, followed by openness and emotionality.

Equipping for the Work of Ministry

For the Christian leader, this information is useful for equipping followers for ministry that will build up the body of Christ (Eph. 4:11–13). Gratitude expression increases both the ability and motivation to perform ministry. If a Christian leader expresses gratitude to people for something they did, it informs the people that what they have done is valuable in the eyes of the leader and the Christian organization that s/he represents. This enables people to focus their energies and persist with greater certainty that such actions are important and valued. Similarly, gratitude expression from a Christian leader motivates the person to continue the ministry. Expressions of gratitude show that the Christian leader appreciates the person, is likely to maintain the relationship with the person, and will likely offer help if needed. These rewards motivate the person to continue. By focusing their followers’ attention on what is most important, Christian leaders can lead their organizations to fulfil their mission (Dunaetz & Priddy, 2014; Warren, 1995) and improve that which most needs improving (Dunaetz & McGowan, 2019).

Nevertheless, Christian leaders should avoid thanking only people whose ministry is salient (e.g., a worship team on Sunday mornings). Leaders can use opportunities where public gratitude is appropriate to thank those whose ministry is clearly visible, as well as those who have a less visible ministry (e.g., one week, parking attendants can be thanked publicly, another week, kids ministry volunteers, and so on). This not only encourages the people working in these less visible ministries, but it also informs the broader audience that these ministries exist and that they are important. Public gratitude can become a motivator to get more people involved in these ministries, especially when there is a shortage of workers and significant ministry opportunities.

For example, most churches have children’s ministries that depend on many volunteers. To motivate greater participation in these ministries, Christian leaders can publicly thank the volunteers in general, as well as specific volunteers who make an especially important contribution. By pointing out exactly the praiseworthy contribution of these individuals, Christian leaders also provide information about the behaviors that are especially valued (e.g., listening to children, preparing dynamic lessons, organizing special events, etc.). This contributes to the training and development of both current and potential volunteers.

Costly Gratitude Expressions are Most Appreciated

This study has indicated that some forms of gratitude expression are more appreciated than others. Although the study’s purpose was not to discover why some forms of gratitude appreciation are more valued, a clear pattern emerged. The least appreciated form of gratitude expression was public and then small group. Gratitude expression received through a written note was more appreciated, but the most appreciated form was individual, private expressions of gratitude.

The more costly the gratitude expression is, the more it is appreciated. Public expressions of gratitude rarely last more than a few seconds and rarely involve a personal exchange of dialogue or close interaction. Small group expressions of gratitude tend to be short in duration and may involve a bit of dialogue, but the dialogue may be formal, ritualistic, or shallow, especially if the person receiving thanks does not want to draw attention to him- or herself. However, a written note of thanks is more costly in terms of time and effort required, especially if handwritten, and likely contains personalized information that the recipient can reflect upon as long as desired. Individual, private expressions of gratitude are the costliest, especially if they involve intentional displacement to thank a person; such encounters also invite dialogue and promote growth in relational closeness. It is probably for this reason that individual, private expressions are the most appreciated form of gratitude.

Personality Effects

Three personality factors from the HEXACO model of personality, conscientiousness, emotionality, and honesty-humility, were the most influential in predicting a person’s appreciation of the various forms of gratitude expression.

Conscientiousness

Highly conscientious people appreciated all four forms of gratitude expression more than less conscientious people. Conscientious people are hardworking, persistent, and faithful (Barrick & Mount, 1991, 2000). They are often the backbones of their organizations, carrying out responsibilities consistently over long periods. They likely appreciate gratitude expressions the most because they have made the greatest efforts to give to others and the organization. Christian leaders need to avoid taking such people for granted and thank them regularly for their consistent service.

One suggestion for Christian leaders would be to personally thank every volunteer in the church on their fifth, tenth, fifteenth (and so on) anniversary of serving in the specific ministry. As long-term persistence is a sign of conscientiousness, such gratitude is likely to be especially appreciated. Keeping track of long-term ministry involvement may be difficult, but expressing gratitude for consistent service makes it more likely that such service will be continued and that others will be motivated to serve in the same way.

Emotionality

Emotionality also predicted a greater appreciation for all forms of gratitude expression (except for public thanking, perhaps because of concerns of being singled out in a large group). People high in emotionality tend to be fearful, unsure of themselves, and sentimental (Ashton et al., 2014). Gratitude expressions for people with such doubts and fears can be especially meaningful because they provide assurance that what people are doing is valuable and should be continued. The more personal, costly forms of gratitude expression from a Christian leader may be especially appreciated because they provide assurance that the relationship with the leader is healthy and that the leader is trustworthy. Written notes may be especially effective because of their sentimental and permanent nature.

Honesty-humility

People high in honesty-humility especially appreciated the more private (written and individual) expressions of gratitude expression. However, people low in honesty-humility especially appreciated the more visible expressions of gratitude expression, both public and small group. People low in honesty-humility are arrogant, dishonest, and narcissistic (Ashton et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2013). From a biblical perspective, this is an extremely dangerous set of traits—traits to which God is opposed (James 4:6). These traits may be characteristic of “wolves in sheep’s clothing” (Matt. 7:15). When in leadership, such people may severely hurt both the organization and individual members (Dunaetz, Cullum, & Barron, 2018; Dunaetz, Jung, & Lambert, 2018). Efforts to be recognized publicly can warn Christian leaders who may thus avoid empowering or putting people who make such efforts into leadership positions.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, responses to the forms of gratitude expression were measured in terms of appreciation by the person being thanked. Other measures of the value of gratitude expression could have been used, such as happiness experienced or personal satisfaction of the person being thanked. These measures could lead to other results concerning the relative importance of the different forms of gratitude expression. In addition, participants were from a broad background, not just Christians or people who attend churches; such a limitation may have influenced the results, but it is difficult to say in what ways. Thirdly, this study was correlational in nature and cannot demonstrate causation. For example, the data was interpreted to mean that having a higher level of conscientiousness causes people to appreciate expressions of gratitude more. However, it is also possible that receiving expressions of gratitude will make a person more conscientious when serving in Christian organizations. Churches and other organizations are complex systems with causation occurring simultaneously in multiple directions.

Conclusion

Expressing gratitude to others in a sincere manner is a natural manifestation of a Christian leader’s gratefulness toward God for what He has done in their lives. In addition, expressing gratitude is a powerful way for Christian leaders to equip those they lead by increasing their service and ministry motivation. The forms of gratitude expression are appreciated differently, and these differences partially depend on the personality of the person being thanked. Christian leaders who follow the Apostle Paul’s example of gratitude expression make a wise choice by recognizing God’s work in and through those they serve and lead.

1Throughout this study, ministry is conceived as specific, discreet actions that are performed and can be performed again. In reality, Christians in many ministries (e.g., teaching Sunday School) are expected to work repeatedly, and the ministry is perceived as being continual, rather than composed of discrete actions. For example, a Sunday School teacher is more likely to say she’s been teaching for four years rather than say that she’s taught 200 lessons.

2In some cultural contexts, this feeling of obligation that one feels to one’s parents or to other important people may express itself as the worship of saints or ancestors. This sentiment can be brought under the Lordship of Christ by recognizing God as the ultimate benefactor (the One who has given us something of value) and one’s heritage (parents, ancestors, other Christians) as the object of value. We should be thankful to God for our ancestors, parents, or other Christians.

References

Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6, 455–469.

Algoe, S. B., Dwyer, P. C., Younge, A., & Oveis, C. (2019). A new perspective on the social functions of emotions: Gratitude and the witnessing effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Advance Online Publication.

Algoe, S. B., Fredrickson, B. L., & Gable, S. L. (2013). The social functions of the emotion of gratitude via expression. Emotion, 13, 605–609.

Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion, 8, 425–429.

Algoe, S. B., Kurtz, L. E., & Hilaire, N. M. (2016). Putting the “you” in “thank you”: Examining other-praising behavior as the active relational ingredient in expressed gratitude. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7, 658–666.

Algoe, S. B., & Zhaoyang, R. (2016). Positive psychology in context: Effects of expressing gratitude in ongoing relationships depend on perceptions of enactor responsiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11, 399–415.

Anderson, N. H., & Butzin, C. A. (1974). Performance = motivation × ability: An integration-theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30, 598–604.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11, 150–166.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2009). The HEXACO–60: A short measure of the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91, 340–345.

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & De Vries, R. E. (2014). The HEXACO honesty-humility, agreeableness, and emotionality factors: A review of research and theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18, 139–152.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1–26.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (2000). Select on conscientiousness and emotional stability. In E. A. Locke (Ed.), The Blackwell handbook of principles of organizational behavior (pp. 15–28). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17, 319–325.

Blumberg, M., & Pringle, C. D. (1982). The missing opportunity in organizational research: Some implications for a theory of work performance. Academy of Management Review, 7, 560–569.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5.

Deutsch, F. M., & Lamberti, D. M. (1986). Does social approval increase helping? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12, 149–157.

Dunaetz, D. R., Cullum, M., & Barron, E. (2018). Church size, pastoral humility, and member characteristics as predictors of church commitment. Theology of Leadership Journal, 1, 125–138.

Dunaetz, D. R., Jung, H. L., & Lambert, S. S. (2018). Do larger churches tolerate pastoral narcissism more than smaller churches? Great Commission Research Journal, 10, 69–89.

Dunaetz, D. R., Lisk, T. C., & Shin, M. (2015). Personality, gender, and age as predictors of media richness preference. Advances in Multimedia, 2015, 1–9.

Dunaetz, D. R., & McGowan, J. (2019). Perceived strengths and weaknesses of American churches: A quadrant analysis of church-based ministries. Great Commission Research Journal, 10(2), 128–146.

Dunaetz, D. R., & Priddy, K. E. (2014). Pastoral attitudes that predict numerical church growth. Great Commission Research Journal, 5, 241–256.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2005). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13, 172–75.

Frijda, N. H., Kuipers, P., & Ter Schure, E. (1989). Relations among emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 212–228.

Grant, A. M., & Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 94–955.

Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In K. R. Scherer & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Lambert, N. M., Clark, M. S., Durtschi, J., Fincham, F. D., & Graham, S. M. (2010). Benefits of expressing gratitude: Expressing gratitude to a partner changes one’s view of the relationship. Psychological Science, 21, 574–580.

Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Stillman, T. F., & Dean, L. R. (2009). More gratitude, less materialism: The mediating role of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 32–42.

Lambert, N. M., Graham, S. M., Fincham, F. D., & Stillman, T. F. (2009). A changed perspective: How gratitude can affect sense of coherence through positive reframing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 461–470.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 329–358.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2005). Psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism in the five-factor model and the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 1571–1582.

Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Wiltshire, J., Bourdage, J. S., Visser, B. A., & Gallucci, A. (2013). Sex, power, and money: Prediction from the dark triad and honesty–humility. European Journal of Personality, 27, 169–184.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

McCullough, M. E., & Emmons, R. A. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377–389.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127, 249–266.

Michie, S., & Gooty, J. (2005). Values, emotions, and authenticity: Will the real leader please stand up? The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 441–457.

Ritzenhöfer, L., Brosi, P., Spörrle, M., & Welpe, I. M. (2019). Satisfied with the job, but not with the boss: Leaders’ expressions of gratitude and pride differentially signal leader selfishness, resulting in differing levels of followers’ satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 1185–1202. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3746-5

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1996). Feelings and phenomenal experiences. In E. T. Higgins & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 443–465). New York, NY: Guilford.

Simmel, G. (1950). The sociology of Georg Simmel (K. H. Wolff, Trans.). Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Sternberg, R. J., & Kaufman, J. C. (1998). Human abilities. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 479–502.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York, NY: Wiley.

Warren, R. (1995). The purpose driven church: Growth without compromising your message & mission. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92, 548–573.

Williams, L. A., & Bartlett, M. Y. (2015). Warm thanks: Gratitude expression facilitates social affiliation in new relationships via perceived warmth. Emotion, 15, 1–5.

Wood, A. M., Emmons, R. A., Algoe, S. B., Froh, J. J., Lambert, N. M., & Watkins, P. (2016). A dark side of gratitude? Distinguishing between beneficial gratitude and its harmful impostors for the positive clinical psychology of gratitude and well being. In A. M. Wood & J. Johnson (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of positive clinical psychology (pp. 137-151).Chichester, UK: Wiley &Sons.

David R. Dunaetz, PhD, is associate professor of Leadership and Organizational Psychology at Azusa Pacific University in Azusa, California.

Peggy Lanum, MS, is a recent graduate in organizational psychology from Azusa Pacific University.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Mark DeNeui of the Institute Biblique Belge (Brussels, Belgium) for his insights concerning a theology of expressing gratitude.