Abstract: This qualitative case study examined the processes and observations of a purposeful sample of four regional districts within the Assemblies of God related to their specific approach to clergy well-being and minister care. A deductive coding process was used to analyze the qualitative data, clarifying themes, including the following: patterns of clergy well-being and help-seeking, the functioning of the Minister Care Model, leadership resistance to adoption of the Minister Care Model by those who use other models, and recommendations for denominational change. This study, while limited in scope, contributes to the literature on clergy well-being by presenting a care-focused model useful to denominational leadership teams.

This article presents a qualitative case study that highlights the unique approach of four districts within the Assemblies of God U.S. to provide care for their ministers. The need for minister care has been well-established in the literature, as pastors experience high rates of occupational stress, burnout, and depression (Biru, Yao, Plunket, Hybels, Kim, Eagle, Choi, & Proeschold-Bell, 2022; Kansiewicz, Sells, Holland, Lichi, & Newmeyer, 2022; Proeschold-Bell, LeGrand, James, Wallace, Adams, & Toole, 2011; Proeschold-Bell, Miles, Toth, Adams, Smith, & Toole, 2013; Tanner & Zvonkovic, 2011). Despite these high emotional needs, pastors, ministers, and clergy tend not to readily seek help for emotional problems (Biru et al., 2022; Kansiewicz et al., 2022; Trihub, McMinn, Buhrow, & Johnson, 2010). In part, this lack of help-seeking can be attributed to the fact that pastors are generally a male-dominated population (Good & Wood, 1995; Levant, Stefanov, Rankin, Halter, Mellinger, & Williams, 2013). However, other factors have been shown to influence clergy help-seeking, including views of male-role norms, age, education level, and one’s number of close friends (Biru et al., 2022; Kansiewicz et al., 2022). Biru and colleagues (2022) found that about half of United Methodist clergy who had elevated levels of depression and anxiety had not sought professional help in the prior two years. Given the barriers to mental health help-seeking on the part of the clergy population, denominations and ministry networks have a responsibility and opportunity to attend to their members’ needs. Before describing the present study, we will examine the literature related to denominational support typically offered to pastors.

Denominational Support

While not all clergy members participate in a denomination or ministry network, the focus here is on the resources and assistance that might be offered by denominational leadership for affiliated ministers. Research has shown that peer support within a network of ministers positively impacts minister well-being (Lutz & Eagle, 2019; Miles & Proeschold-Bell, 2013). Lutz and Eagle (2019) reported that clergy tend to seek out help from spiritual directors and spiritual leaders. Trihub and colleagues (2010) noted that denominational networks tend to offer prayer, retreats, conferences, and sabbatical support, which are well-received by ministers. However, there are ways in which denominations have not always provided care or emotional support to their members but rather have had a punitive approach to those seeking out their help. For example, several have noted that clergy are reticent to admit mental health needs to denominational leaders due to fears of losing their credentials (Edwards, Sabin-Farrell, Bretherton, Gresswell, & Tickle, 2022; Meek, McMinn, Brower, Burnett, McRay, Ramey, Swanson, & Villa, 2003; Trihub et al., 2010). These studies reveal a historical pattern of the potential for job loss for ministers who express mental health needs to their denominational leadership. Thus, denominational and ministry network leaders must consider ways to separate the process of offering emotional care from the employment and credentialing process. At present, there is little research that illuminates the denominational procedures and processes of responding to the emotional needs of ministers.

Assemblies of God Leadership Structure

The Assemblies of God U.S. is comprised of 66 regional and language districts. Their national headquarters, located in Springfield, Missouri, houses the executive leadership team, including a general superintendent, assistant general superintendent, general secretary, general treasurer, U.S. missions director, and world missions director. Rather than operating with a top-down leadership structure, the Assemblies of God U.S. focuses on providing support for their “self-governing” affiliated churches (Assemblies of God, 2023). Districts provide ministry networks but similarly do not govern individual churches nor do they appoint or place ministers in job positions. Both the districts and the national office provide a credentialing process in which pastors can become credentialed, licensed, or ordained ministers. Disciplinary action can be taken if pastors engage in “sexual misconduct, financial misconduct, relational/ethical misconduct, or substance use/abuse” (Assemblies of God, 2023, p. 65). While there have been efforts to clarify the bylaws over the course of many years to specify the exact nature of disciplinary issues, there has been anecdotal evidence that ministers within the Assemblies of God have historically avoided help-seeking out of fear of losing credentials or ministry positions. To date, there has not been any formal research to examine such a trend.

Purpose of the Study

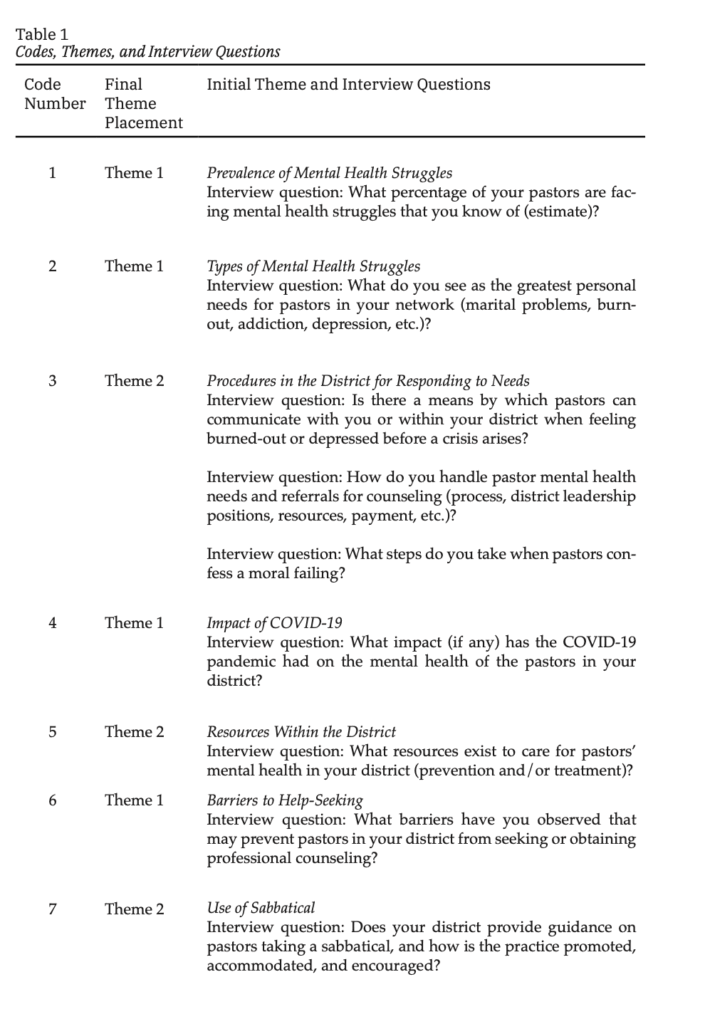

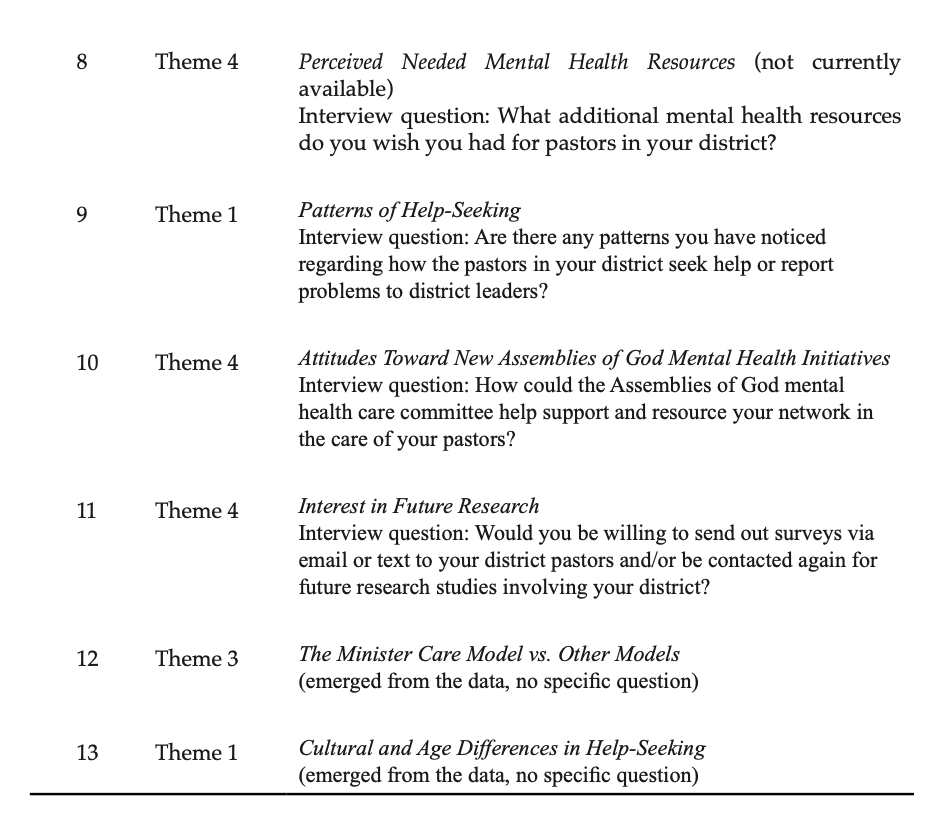

The purpose of this study was to conduct a qualitative case study of four Assemblies of God U.S. districts who provide minister care in a confidential manner that is separated from disciplinary action. The author sought to understand the processes and observations of these district leaders to understand their unique approach to minister care that is not represented in most other districts within the Assemblies of God. The primary research questions were the following: What types of mental health needs have these leaders seen within their districts? What processes do they use for minister care (including in cases of moral failure)? What mental health resources do they use or have available to them? (A full list of the semi-structured interview questions can be found in Table 1.)

Method

The present study was a qualitative case study using a deductive method of analysis. The author conducted semi-structured interviews after obtaining approval from the university’s human subjects review board. Using purposeful sampling, the research team identified Assemblies of God districts (also referred to as “networks”) around the United States that had a district-level position specifically focused on minister care. The four districts identified have similar processes and structures in place to provide confidential and emotionally supportive minister care; thus, a case study approach was chosen to examine the model of minister care within these districts. Leaders from the four identified districts agreed to participate in the study to describe their approach to minister care and provide insights related to clergy well-being. While these districts may not be the only districts focused on minister care, they are among only a handful of Assemblies of God districts in the U.S. that employ someone at the district level specifically dedicated to minister care. The four districts represented are in different geographic regions across the United States.

Question Development and Analysis

The Assemblies of God U.S. national office initiated a mental health committee in 2018 to work on improving resources that provide for minister care and well-being. The committee provided some questions of interest to this author that were used as a springboard for creating the semi-structured interview. The goal was, in part, to understand the nature of clergy well-being as experienced by these districts along with gaining insights into the processes by which these districts offer care to their ministers. Because the questions fell into clear categories at the outset, researchers used a deductive coding process (Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019). An initial 11 codes were identified, linked to specific interview questions, prior to data analysis.

After obtaining a signed informed consent, semi-structured interviews were conducted virtually and were recorded and transcribed. Three of the districts had one leader interviewed and the fourth district had two leaders present in the interview. The research team was composed of the author and two research assistants who each cleaned transcripts and independently coded the data. After individual data coding, the research team met to compare analyses. During the coding process, all three coders placed each piece of meaningful data into a spreadsheet labeled with the initial 11 codes. Upon comparison, all three members of the team had agreement on where they had placed responses into the codes, except for some data that did not fit into the initial codes. This agreement was not difficult because the data largely fell within the interview questions that were designed to elicit specific information. The team created two additional codes to provide clarity on data that emerged during the interviews that did not fit into the initial codes (see Table 1). Collaboratively, the team discussed overlap of these 13 codes and identified similarities in the responses. Through this deductive process, the team was able to reduce the original codes to four umbrella themes. These will be presented in the results section.

We aimed to ensure trustworthiness in the coding process through predetermining our codes prior to deductive analysis, independent placement of data into these codes, and collaborative decision-making on data that did not fit into the initial codes. We have included the questions and codes in Table 1 in order to allow the reader to further assess the trustworthiness of our approach and conclusions. Further, we provided the manuscript of this article to each of the study’s participants for review and comment prior to submission to ensure accuracy in the representation of the interview data and conclusions reached.

Results

The team reduced the 13 codes (presented in Table 1) to four categories, presented below as themes with sub-themes. Theme 1 was made up of codes 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 13. Theme 2 was made up of codes 3, 5, and 7. Theme 3 was exclusively represented by code 12 and emerged from the data without a question seeking this direct information. Finally, Theme 4 combined the initial codes of 8, 10, and 11. The remainder of this section presents a description of these themes illustrated by rich data quotes and provides a case study for an approach we are calling the “Minister Care Model” used by these four participant districts.

Theme 1: Patterns of Clergy Well-Being and Help-Seeking

Many of the interview questions focused on well-being and help-seeking of ministers within the districts represented. Thus, the first theme had the largest number of codes and presents insights into the frequency and nature of emotional challenges faced by pastors, along with their typical patterns when seeking help. Regarding the frequency of mental health problems, there was a range of numbers offered. Two of the participants estimated around 50% of their pastors had some type of mental health challenge, while the other two participants estimated much lower at “2–3%” and “5–10%.” The participant with the lowest estimate clarified that this was an estimate of diagnosable mental illness, as opposed to other participants who seemed to include a broader range of emotional stressors, including burnout or “elevated stress.” These numbers are not assumed to be accurate but rather represent the perceptions of the district leaders interviewed. A prior quantitative study of Assemblies of God ministers conducted by this author showed that approximately 14.1% experience moderate or higher depression (Kansiewicz et al., 2022).

The overall nature of mental health challenges described by the participants included personal struggles, such as marital/family conflict, social isolation, anxiety, pornography addiction, or “a lack of healthy rhythms.” Other aspects of the challenges they described focused on occupational struggles, such as pressures from their congregation, a sense of urgency in evangelism or outreach, financial strain, and changing congregational dynamics with the COVID-19 pandemic. Each of these stressors were named as factors having a direct impact on the overall well-being of ministers. One participant reflected on the insights of one pastor within the district that was representative of many ministers and the new stressors and pressures they face since the pandemic:

What is church ministry now? And what does it mean to pastor now? I didn’t sign up to pastor an online church. That’s not what I got into minis- try for . . . that I could speak to a screen and be, you know, what used to be a televangelist.

Another participant shared:

And it’s all brought about by the circumstances you know, a pandemic/political environment. It’s very toxic, all of that coming together. So, I don’t think there’s a pastor that could avoid that, or just because they have a healthy church if they haven’t been able to meet for six months. How do you, you know, how does that factor into the health of the congregation? It’s difficult to keep the momentum. So, for many of our churches, it’s just been a real crisis.

While these interviews were conducted in the spring of 2021, the impacts and ongoing nature of the pandemic as well as political polarization are likely continuing factors affecting ministers’ well-being. Further research could illuminate the longitudinal effect of these stressors specifically.

Regarding help-seeking patterns, these participants described a variety of barriers that prevent their ministers from seeking professional counseling or other mental health treatment. Examples included stigma, fear of losing ministerial credentials or their ministry position, a belief that they should handle their own problems themselves, cost, and fear of running into a parishioner in a counseling office waiting room. One participant stated,

At least within our AG circles, it is how we view what good leadership is all about. We do it alone, and there are not the structures in place to provide safe relationships and ongoing lasting relationships with other peers.

Several participants noted generational differences in help-seeking patterns, with younger ministers having a “hunger for authenticity” and more likely to seek professional counseling than older pastors. The participants drew the line between ages 40 and 45 where the generational differences lie. One stated,

I think it seems to me that many of the younger ones . . . there’s an openness, transparency and an honesty that seems to be there I think there’s an older kind of generation that [thinks], “We can talk it through [ourselves]. We can make it.”

Leaders in three out of the four districts mentioned a pattern in which ministers tended to wait until a crisis to contact the district leaders and/ or seek professional help for mental health problems. Some pastors seem to prefer informal modes of support, such as talking to peers or spiritual direction/resources. There was a noted interest in life coaching or ministry coaching over professional counseling on the part of some pastors.

Theme 2: The Minister Care Model

The second theme describes the processes by which these districts care for their ministers and explores the resources they employ to provide this care. All the participants used the term “minister care” in their descriptions and in the job titles of the district-level positions dedicated to providing care to their ministers. Thus, we believe that the Minister Care Model is an appropriate term to describe the approach of these districts, and this was affirmed by the participants. Theme 3 will describe the processes by which other Assemblies of God U.S. districts have historically handled problems and will describe resistance that has been expressed on the part of other district leaders about using the Minister Care Model. Here we will examine the unique approaches used by these districts that highlight a specific model.

The first distinctive of the Minister Care Model is the presence of a person employed part-time or full-time at the district office who has a dedicated role focused on providing care to ministers. In each of our participant districts, there were provisions for additional confidentiality afforded to the person in this role as an effort to reduce the fear of loss of credentials when seeking help. One participant described the role this way:

The director of minister care . . . under that [is] counseling, reference, resourcing, mental health care, sabbaticals, financial, . . . really everything that would come to every level of every minister…… Social ministry, marriages, ministry families, you know, we’ve done this PK retreat for ministry kids that would come under there.

The director does not solely provide the care described above, but in general leads a team of minister care representatives. One district has a larger network of retired ministers that provide care to a smaller subset of ministers within the district. These care providers operate on a volunteer basis and are encouraged to be the first person reached out to when a minister is struggling.

The participants emphasized the importance of confidentiality in the Minister Care Model, describing it as another distinctive of the model. One stated,

So, when you’re setting up these systems of care [it is important] that the ministers clearly know that [the minister care team] can guarantee confidentiality and where can they guarantee confidentiality. That’s so important [just like] a therapist or a counselor to their client.

While those outside a ministry context may not find the need for confidentiality surprising, the practice is fairly novel within a denominational structure. Reasons for this will be highlighted in the presentation of Theme 3. The participants made a distinction between emotional struggles or problems of the minister versus direct moral failings. Such a distinction has not always been made in relation to confidentiality as well as threat of loss of ministerial credentials.

A third distinctive practice in the Minister Care Model is the focus on prevention. The participants described efforts on the part of the districts to offer video or print resources, monthly email blasts, social media groups, peer groups, and other forms of information sharing about mental health topics. One participant stated, “It’s a proactive approach to help raise their awareness of the things that can stress them out.” The following quote reflects the preventative and supportive goals of peer groups offered in one district:

We all get wounds in ministry, but not all wounds have to get infected. And so the moment that we have others to identify with, to process that with . . . we can bring healing to one another, not just circulate our wounds…… They’re able to deal with it in a very healthy, safe environment. And it doesn’t have to get to a level 10.

Another participant stated their aim was to “build a culture” of talking about stressors and emotional problems amongst the ministers. The national office of the U.S. Assemblies of God has also taken some steps to encourage a culture of help-seeking by printing mental health and suicide hotline numbers on the back of the credentialing card and in 2022 (after data collection for this study) adding a new website focused on prevention and mental health resources (MinisterFamilyCare.AG.org). The participants in this study described enthusiasm for national prevention and resource initiatives and advocated for ongoing policy shifts in how districts handle ministers who are burning out or struggling emotionally. These desires and recommendations for change will be further highlighted in Theme 4.

A final distinctive of the Minister Care Model is the direct financial and resourcing support that they offer to connect their ministers to professional counselors. All the participants expressed positive beliefs about professional counseling and described networks they have created in their local areas with Christian professional counselors. Some of the participant districts noted that they have some funding to pay for clinical assessments or up to five sessions of professional counseling for a minister in need. The districts also aim to help ministers find counselors who can accept their health insurance for long-term professional care. The participants also described minister retreats that they have hosted, along with sabbatical support for ministers who are burned out or feeling on the edge of burnout. One participant stated,

I have developed a network of leaders who I’ve coached through their sabbatical and walk through the sabbatical. We’ve created plug and play, or cut and paste, documents that would go into bylaws so that it’s hardwired into the local church to offer sabbaticals.

The participants described a historical culture of avoidance of sabbaticals on the part of ministers who fear that there is no one to care for their churches in their absence—as well as on the part of church boards who do not want to pay a three-month salary for a leave of absence. As is evident in the quote above, Minister Care Model districts are providing coaching, guidance, and even policy for churches in order to enable pastors to take sabbaticals periodically in their ministries.

Theme 3: Leadership Resistance to the Minister Care Model

Few Assemblies of God districts in the U.S. have adopted the Minister Care Model. While we did not ask an interview question about the views or practices of other districts, this theme emerged from the participant responses that shed light on some cultural and historic reasons that other districts have not adopted such a model. One participant described a conversation with a leader from another district expressing surprise at the informality and confidentiality of minister care:

They inquired, “Really, they can come to you?” . . . That’s, like, a totally brand-new thought process because normally it’s . . . “We’ve got to take that to the superintendent. And we’ve got to get a formal thing going.”

The “formal thing” noted here is the process described in the Assemblies of God bylaws related to a disciplinary process after specific moral failings. One participant stated that this restoration process is still in place with the Minister Care Model, but it is generally limited to “sexual misconduct, child abuse, or criminal activity” and does not need to include more basic emotional struggles, burnout, or poor coping strategies. In many districts, the district superintendent is the first responder to any minister problems, and historically the focus has been on credential maintenance or loss. Due to the help-seeking pattern of waiting for crisis mentioned in Theme 1, district superintendents may not be aware of problems until there is a crisis. Given the crisis, sometimes there is not a path forward in this approach other than removal from ministry.

Some leadership resistance related to use of the Minister Care Model was evident in this conversation relayed by a participant:

And the [other district] superintendent’s response [to the Minister Care Model] was, “Wow, I couldn’t do that. I’ve got to know what’s going on.” And our superintendent said, “It’s going on. They’re just not telling you because they don’t have an outlet, and the fear factor of losing a ministry or at least being taken out one or two years is kind of a big deal.”

Other participants also described the culture within the Assemblies of God as being that the district superintendent should be informed of the problems of the ministers and that loss of credentials or ministry position would be at times a first response of the superintendent. The participants also described a historic lack of clarity about what actions or problems would require a loss of credentials or a formal restoration process. In particular, pornography use has been a gray area when it comes to a formal versus informal process. The participants reflected the wrestling amongst district leaders between formal “restoration” versus a less formal “recovery” process for ministers. One participant noted a “shift in the culture and systems” of the Assemblies of God nationally that is leading to an openness to confidential minister care and more clarity related to when a formal process is required.

Theme 4: Recommendations for Denominational Change

Overall, the participants expressed optimism related to the national mental health committee that general superintendent Doug Clay established and the efforts they have undertaken to resource districts and move toward a positivity around help-seeking. However, there was a call for further action to be taken. The participants in this study offered a variety of recommendations for change even in the midst of their descriptions of a cultural shift that is already underway. One participant expressed a desire for the creation of a position at the national Assemblies of God U.S. office focused on minister care, stating, “I would love to see… an actual department at the national office. We have an executive director or a national director for every single thing but minister care.” This national “Director of Minister Care” would provide policies, procedures, resources, and guidance to the districts in order to help more districts adopt the Minister Care Model. Other participants expressed a desire for increased national conversations about mental health topics, and all noted a positive increase in anti-stigma language from the Assemblies of God U.S. national office and the General Superintendent.

One participant expressed their passion for change this way:

I have been very vocal for the last two years that, if we don’t get this right, all the other things really pale, because . . . I think healthy ministers produce healthy ministry. And so, if we just talk about all the ministry we’re doing, but don’t give care to ministers, we have shipwrecked the strategy and we’re never going to get anywhere. And then there’s just a personal passion I have of being with a community of leaders that are caring for each other.

Other specific suggestions for continuing to move toward larger adoption of the Minister Care Model and to reduce stigma included ongoing research on the topic, development of a national counselor referral list, and provision of more video-based resources to encourage minister mental health. One participant suggested additional qualitative research using focus groups of pastors around the country to hear directly from these ministers about the stressors they face and the resources they seek. The participants also encouraged use of remote (telehealth) mental health services for pastors, which might reduce some barriers to help-seeking. One participant stated that any efforts that increase awareness of “the complexity of the human condition” and the ways that ministers are not exempt from these human struggles would be welcome.

Discussion

The interviews with all four participant district leaders in this study carried an overall tone of hopefulness in the midst of a sense that there is more work to do in decreasing stigma and increasing help-seeking amongst pastors. Even since data collection in 2021, additional steps have been taken in line with what was described in our interviews, such as the development of a national counselor referral list, which has been taken on by the General Secretary in the Assemblies of God U.S. national office. While this qualitative case study presents the Minister Care Model, the data collected in this study also suggests that the culture is already beginning to shift toward a wider adoption of such a model. The districts who are already using such a model can offer a pathway for other Assemblies of God districts and other ministry denominations who are seeking to move in this direction.

Implications

While this study’s data suggests that there are denominational leaders around the country seeking to change the way ministers are cared for, we do not know how the ministers themselves want to engage with such care. From our participants, it appears that their ministers are engaging with the minister care they provide and that their prevention strategies are well executed. However, this study does not tell us how many ministers open and view a video or email blast on a mental health topic. There is no comparison of minister engagement with the districts who use a Minister Care Model and those that do not. Additional research is needed to determine how the pas- tors themselves view the Minister Care Model and if such a model changes their engagement with their denominational leaders. These inquiries could be done through quantitative measures of minister engagement with various interventions, as well as through qualitative evaluation of pastors’ feelings and perceptions of these interventions. A grounded theory study would be useful to explore why pastors may or may not engage with district leadership when they need emotional support or care.

The first theme supports what is found in the literature: ministers have unique stressors and occupational challenges that impact their mental health (Biru et al., 2022; Kansiewicz et al., 2022; Proeschold-Bell et al., 2011). The data collected in this study suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has added to this list of clergy stressors, and it is uncertain how long the impact of the pandemic will continue to affect the ways that pastors do their jobs. Additional research is needed to understand the specific stressors that pastors now face, including clergy reactions to establishing or maintaining an online presence. Further research can also examine the second theme by comparing the Minister Care Model with other forms of denominational leadership to determine if such a model reduces stressors or impacts help-seeking patterns. A wider survey of denominational approaches to minister oversight and support could shed light on other models that exist, which could lead to comparative studies on the effectiveness of those leadership and care models.

Theme 3 offers some insights related to barriers to using the Minister Care Model at the denominational level, and these barriers can be explored further. Are there differences between leaders who want to use a Minister Care Model and those who do not? What historical and cultural factors continue to prevent leaders from feeling comfortable with increased confidentiality when ministers share their emotional struggles or problems? Are there strategies that can assuage potential fears? What strategies do pastors most willingly embrace? If pastors do not prefer to discuss problems with denominational leaders, are there other resources that they would use more? How can denominations support the use of these additional resources? These are some of the many questions that arose from our study.

Overall, this study provides important insights related to shifting views specific to the Assemblies of God on minister well-being and care. As one of the larger networks in the United States, it is possible that a culture shift within the Assemblies of God could reflect a wider shift across other denominations or that the Assemblies of God could lead the way in emphasizing minister well-being and care. Given the noted differences in help-seeking by age group, there may be an ongoing trend toward a positive view of self-care, wellness, and help-seeking amongst pastors as older pastors retire and younger pastors take on more leadership roles (Kansiewicz et al., 2022). In the midst of such a culture shift, it is important for counselors, mental health advocates, and denominational leaders to develop a variety of resources for pastors to use.

Once again, the development of any such resources should include qualitative and quantitative research on which resources pastors are most likely to use. Qualitative research can provide detailed insights on the preferences of ministers that can feed quantitative surveys or group comparisons on engagement level for broader generalizability. Counselors and denominational leaders may instinctively lean toward establishing more session-based counseling services or referral networks, but other opportunities such as retreats, seminars, and trainings may be more palatable to clergy. Taking a coordinated approach is difficult across a wide spectrum of ministers, so it may be necessary to identify national leaders who can coordinate research and resource development. Duke University has been one example of a leader in this arena, but their focus within the United Methodist Church may not fully address cultural factors within conservative White evangelical spheres. In addition to comparisons between theologically distinct denominations, it is important to note and explore the differences between ethnically defined churches or districts in how they perceive or provide minister care.

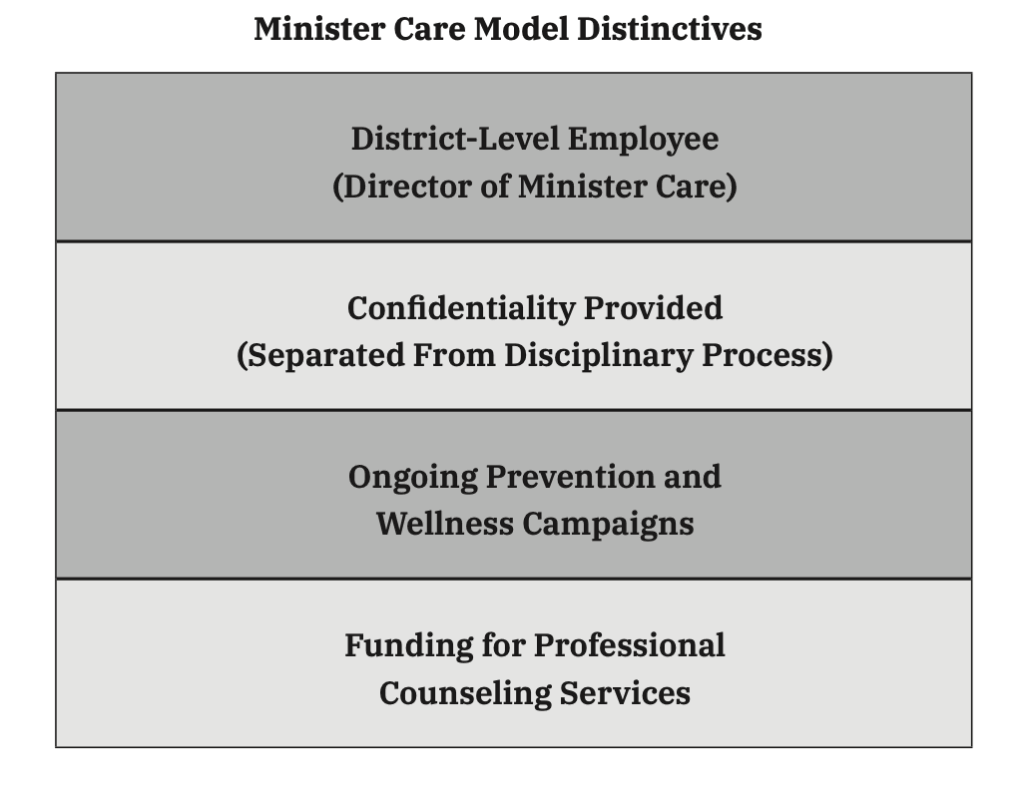

Implications for Leaders of Christian Ministry Networks

For those who are in denominational leadership roles or teach and train upcoming ministers, this qualitative case study presents a model that can be replicated in a variety of contexts. The four distinctives of the model (see Figure 1) provide specific steps that can be taken: (1) Establish a part- or full- time position at the denominational or leadership team level that oversees systems of minister care, (2) ensure that the providers of minister care can protect confidentiality, (3) engage in prevention strategies to educate pastors and build a culture of well-being, and (4) raise funding to pay for counseling services and other supportive programming for ministers seeking help. In addition, denominational leaders can evaluate their own fears about using such a model. What are the barriers to implementation? If such barriers exist, do they also contribute to a culture that discourages help-seeking? All Christian leadership structures who oversee ministers can conduct a systemic evaluation of the implementation of the Minister Care Model, along with evaluation of the challenges and strengths of current systems.

Figure 1

Distinctives of the Minister Care Model

Strengths and Limitations

This study has provided insights into an emerging model within the Assemblies of God and presents an example for other districts, ministry networks, and denominations to follow. These data add to the literature as we seek to understand how minister care can be most effectively delivered on a national scale. Our participants represented different regions around the United States, suggesting that the Minister Care Model is not limited to only a small geographic segment. This study also did not include the non-English language districts within the Assemblies of God, so the results presented represent a predominantly White viewpoint.

While useful in presenting a case study on a specific model of clergy care, this study is small and can be regarded as a pilot study. Certainly, there are a variety of questions that require further research that will shed additional light on the subject. This study does not provide data on the effectiveness of the strategies of the Minister Care Model, nor does it offer a comparison to other groups using alternative models. The implications for this study may not apply to all groups of ministers, and the cultural shifts noted may be unique within the Assemblies of God or perhaps even limited to the participants of this study. Additionally, there is potential for bias as acknowledged earlier due to the lead researcher’s affiliation with the Assemblies of God. These limitations should be taken into consideration when considering the insights that the study does offer.

Conclusion

This qualitative case study used a deductive method to analyze interview data from district leaders in four districts within the Assemblies of God. The identified themes highlighted mental health needs and help-seeking patterns, presented the Minister Care Model, discussed leadership resistance to the use of the Minister Care Model in some other districts, and provided recommendations for change in denominational leadership approaches. This study highlights a cultural shift within the Assemblies of God that was evident not only in our participants’ statements but in additional steps taken by the U.S. national office of the Assemblies of God. Further research can add to this study by evaluating the effectiveness of the Minister Care Model and comparing this model to other districts and denominations. Overall, research on clergy well-being and help-seeking can continue to direct attention toward minister care, which can in turn improve the health of ministers and their congregations.

Kristen Kansiewicz, PhD, LPC, is an assistant professor of counseling at Evangel University and is co-founder of The Refuge, a non-profit in Springfield, Missouri, that supports minister wellness.

References

Assemblies of God (2023, August). Constitutions and bylaws of the general council of the Assemblies of God. Assemblies of God. https://ag.org/About/About-the-AG/ Constitution-and-Bylawsc

Biru, B., Yao, J., Plunket, J., Hybels, C. F., Kim, E. T., Eagle, D. E., Choi, J. Y., & Proeschold-Bell, R. J. (2022). The gap in mental health service utilization among United Methodist clergy with anxiety and depressive symptoms. Journal of Religion and Health, 62(3), 1597–1615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01699-y

Edwards, L., Sabin-Farrell, R., Bretherton, R., Gresswell, D. M., & Tickle, A. (2022). “Jesus got crucified, why should we expect any different?”: UK Christian clergies’ experiences of coping with role demands and seeking support. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 25(4), 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2022.2059068

Good, G. E., & Wood, P. K. (1995). Male gender role conflict, depression, and help seeking: Do college men face double jeopardy? Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1995.tb01825.x

Kansiewicz, K. M., Sells, J. N., Holland, D., Lichi, D., & Newmeyer, M. (2022). Well-being and help-seeking among Assemblies of God ministers in the USA. Journal of Religion & Health, 61(2), 1242–1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01488-z

Levant, R. F., Stefanov, D. G., Rankin, T. J., Halter, M. J., Mellinger, C., & Williams, C. M. (2013). Moderated path analysis of the relationships between masculinity and men’s attitudes toward seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 392–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033014

Linneberg, M., & Korsgaard, S. (2019, May). Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3), 259–270.

Lutz, J., & Eagle, D. E. (2019). Social networks, support, and depressive symptoms: Gender differences among clergy. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 5, 1–9.

Meek, K. R., McMinn, M. R., Brower, C. M., Burnett, T. D., McRay, B. W., Ramey, M. L., Swanson, D. W., & Villa, D. D. (2003). Maintaining personal resiliency: Lessons learned from evangelical Protestant clergy. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 31(4), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164710303100404

Miles, A., & Proeschold-Bell, R. J. (2013). Overcoming the challenges of pastoral work? Peer support groups and psychological distress among United Methodist Church clergy. Sociology of Religion, 74(2), 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/ srs055

Proeschold-Bell, R. J., LeGrand, S., James, J., Wallace, A., Adams, C., & Toole, D. (2011). A theoretical model of the holistic health of United Methodist clergy. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(3), 700–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10943-009-9250-1

Proeschold-Bell, R. J., Miles, A., Toth, M., Adams, C., Smith, B. W., & Toole, D. (2013). Using effort-reward imbalance theory to understand high rates of depression and anxiety among clergy. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(6), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-013-0321-4

Tanner, M. N., & Zvonkovic, A. M. (2011). Forced to leave: Forced termination experiences of Assemblies of God clergy and its connection to stress and well-being outcomes. Pastoral Psychology, 60(5), 713–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11089-011-0339-6

Trihub, B. L., McMinn, M. R., Buhrow, W. C., Jr., & Johnson, T. F. (2010). Denominational support for clergy mental health. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 38(2), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164711003800203