Abstract: Our fast-changing global society is in need of a new type of leadership. This leadership must foster know-how and know-why, abilities to perform and conceptual ways to create meaning. How can such leadership be developed? Three faculty members from a graduate leadership program share their discoveries about leadership development from working with hundreds of leaders. They share the history and characteristics of the program and the emerging theoretical understandings on leadership development that guide the program. They explore the confusion over what can or cannot be taught in leadership, the tension between scholarship and practice, and the role and place of individual and community development. They use these issues to support their fundamental observation that learning theories and processes must be central in growing leadership capacity in individuals and institutions.

Keywords: Leadership development, leader development, Kolb Learning Cycle, experiential learning, competency-based learning, constructivism, instructivism, connectivism, portfolio, reflection, transmission-based education, job-embedded learning, narrative knowing, contextual knowing, wisdom, social learning, transformational leadership.

Richard pastors a large church plant with six satellite campuses in a suburban area of the United States. The church has also started a school, an orphanage, and a community food bank, and his denomination has an offer to assume ownership of the local community hospital. While Richard has been encouraged by God’s leading in this church over the past 20 years, he is concerned about extending his members’ resources and expanding into areas in which they have no direct experience. He contacts the president of his conference, wondering how he can discern God’s leading and asks for guidance. What advice do you give?

Denise is dean of graduate studies at a thriving Christian university. She sees possibilities for expanding the programs her institution offers on a much wider scale by collaborating with other universities—but this requires confronting stagnant thinking by those who fear change. The issues come up in a meeting with the university president. How do you help your institution fulfill its potential for growth and excellence?

In today’s organizations there is an enormous weight of responsibility and expectations that inevitably falls on leaders. What is the right thing to say and do? How do you know when you’re making a good decision? While decisions have always been difficult and leadership has always been hard, our rapidly changing modern world has complicated matters further. We face financial meltdowns, moral failures, technological opportunities, pluralism and postmodernism. Whether you call these times of great change (Drucker, 1995), a world of permanent white water (Vaill, 1996), highly turbulent environments (Dent, n.d.), a time of fundamental change in society and culture (Wolterstorff, 1997), a culture of fragmentation (Walsh, 1997), or a time when the seas are rough (Hewson, 2009), the reality is that this kind of rapid and often violent change creates ambiguity and confusion. In such dynamic contexts leaders have to expect to encounter issues very different from anything they have seen before with no clearly defined path to take.

Could there be a connection between the context of change we live in and the increase in leadership development programs? Rather suddenly—in the last fifteen years—there has been a proliferation of these programs (Day, 2001, p. 162). Some are short-term in nature, while others are more extensive. Some are offered by colleges and universities, while others are run by military groups, housed in training departments of large organizations, available through professional associations, or promoted by enterprising for-profit groups. Each of these programs hopes to increase the participants’ ability to lead, manage and guide their organizations, communities, churches or schools.

Most programs tend to be a potpourri of activities—activities not necessarily grounded in theory or practice (Ardichvili & Manderscheid, 2008). Sadly, few are built on clearly articulated or researched principles or beliefs. Those few that do have a systematic organization to them often are built on specific business models or certain leadership theories, but fewer are framed around fundamental worldviews. This paper reviews the Leadership Program at Andrews University in Michigan to discuss basic observations about learning leadership. First, a brief history and explanation of the program is given. Second, to help explain our innovative approach to leadership and learning, we explore what actually can be taught and learned in leadership development and how this influences our view of leadership. Because learning is so central to leadership and leadership development, we use a significant section of this paper reviewing the learning theories that have been most helpful to us in our shared experiences of learning with leaders. Next, we look at the goal of leadership, which is also the goal of leadership development—wisdom or the ability to bring meaning from and within change and ambiguities.

We suggest that contextual learning is central in leadership development and wisdom is the best way to capture both the outcome and the process of leadership and leadership development. Threaded throughout the article are descriptions of how the program has changed and is changing as we continue to learn and grow. We have also included strands representing the core spiritual dynamics grounding our work in Biblical principles and giving us strength and a sense of direction as we continue to grow and innovate in this program. We conclude where all leadership concludes—by sharing not only our main discoveries but also the continuing ambiguities and tensions that pester us with questions that keep us growing.

The Andrews University Experience

The Leadership Program was created in 1994 by a group of faculty members in the Andrews University School of Education. Because of fiscal constraints, they had been given the challenge of figuring out how to reduce the total number of faculty members in the school. When the group met, instead of letting faculty members go, it was decided to propose the creation of a new program that would attract a whole new audience—fully-employed leaders in churches, schools, hospitals and businesses who typically would not be able to leave their jobs and homes for traditional campus-based graduate work. To underline their seriousness, several faculty members volunteered to spearhead the program without additional pay on top of their teaching load. When the program started only a few months later in the fall of 1994 with a cohort of some 20 participants, a journey in leadership development began that has not only shaped the leaders who joined the program but also the faculty who chose to venture into a new learning space.

Several features immediately set the Leadership Program apart from traditional graduate programs and created a sustained interest in the program: the job-embedded nature of the program that allows participants to utilize their professional experiences in the academic setting; the opportunity for individual development of “competency” in a variety of leadership areas, rather than a focus on a pre-determined set of class requirements; the development of an individualized plan of study; the portfolio assessment of competency; the use of study groups; and the Roundtable, an annual face-to-face conference. Currently, over 100 doctoral-level and about 50 master’s-level participants have graduated from cohorts in Central and Western Europe, South America, and the United States.

From its beginning, service has been central to the philosophy and mission of the Leadership Program. The tagline “Leadership—A Platform for Service” emphasizes this focus. While servant leadership has been popularized in the secular world by Greenleaf (2002) and Spears, Lawence, & Blanchard (2001), the idea of being a servant is central to the life and teachings of Jesus and thus an ideal model for a Christian leadership development program. When Jesus said, “Whoever desires to become great among you; let them be your servant . . . just as the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve” (Matt. 20:26-28; see also Matt. 24:45, Matt. 25:21, Luke 17:10, Gal. 5:13, Eph. 6:7), he firmly anchored serving in the nature of leadership. Serving is not just an interesting idea, but an expression of who God is. The disciples never forgot the image of the Lord Jesus, the ultimate servant, washing their feet in the upper room. They vividly remembered how He repeatedly chose to serve others—often putting aside His own needs in favor of His followers. For this reason the Leadership Program builds on the idea that “true education . . . prepares the student for the joy of service in this world and for the higher joy of wider service in the world to come” (White, 1903, p. 13).

In the Andrews Leadership Program, the primary opportunity for participants to serve one another is through participation in study groups, also called regional groups or Leadership and Learning Groups. Often in these groups participants review competencies and sign-off portfolio items for one another. They also share personal joys and heartaches with each other. They serve each other in many ways and help one another to make progress—and in serving each other, they increase their capacity to serve in their varied roles in the everyday world.

Fifteen years of learning with leaders who are experienced and employed in various environments has given us a strong belief that learning is central to leadership and therefore to leadership development (Vaill, 1996). Two dissertations focused specifically on the Leadership Program (Alaby, 2002; Rausch, 2007) and helped us understand from a theoretical as well as an experiential perspective how our participants were learning in the program. Other dissertations and research projects have given the faculty, in particular, opportunities to learn new strategies and theories, and to participate in dialogue with the academic community about how leadership development works.

To help explain our innovative approach to leadership and learning, we first explore what actually can be taught and learned in leadership development and how this influences our view of leadership. Out of this process, we show the centrality of learning in leadership and in leadership development. For that reason, we use a significant section of this paper reviewing the learning theories that have been most helpful to us in our shared experiences of learning to lead. Next, we look at the goal of leadership as also being the goal of leadership development—something which we consider to be wisdom or the ability to bring meaning from and within change and ambiguities. We suggest that contextual learning is central in leadership development and wisdom is the best way to capture both the outcome and the process of leadership and leadership development. Threaded throughout the article are descriptions of how the program has changed and is changing as we continue to learn and grow. We have also included strands representing the core spiritual dynamics grounding our work in Biblical principles and giving us strength and a sense of direction as we continue to grow and innovate in this program. We conclude where all leadership concludes—by sharing not only our main discoveries but also the continuing ambiguities and tensions that pester us with questions that keep us growing.

What Can Be Taught and Learned?

In order to think about what can be taught and learned in leadership development programs, it may be helpful to define what leadership development is and how it functions in the Andrews Leadership Program. Several authors have pointed out the difference between leader development and leadership development (Day, 2001; Iles & Preece, 2006; Jones, 2006; McCauley & Van Velsor, 2004). Generally, they concur that leader development focuses on the individual, whereas leadership development involves a broader context of people and processes including, but not limited to, the individual leader.

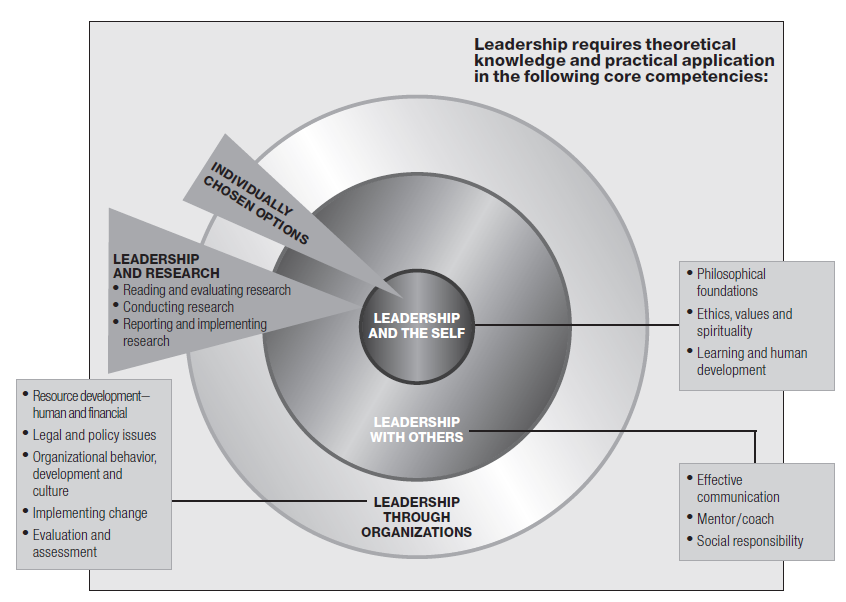

There is a sense that many early leadership development programs— especially in the United States—tended to focus on self-awareness and self-development—or leader development (Jones, 2006). However, the current trend is toward a broader definition that includes both individual development and relationships within organizations. In this way leadership development is seen as “helping people to understand, in an integrative way, how to build relationships to access resources, coordinate activities, develop commitments and build social networks” (Iles & Preece, 2006, p. 323). This trend is also reflected in the list of program competencies that are depicted in concentric circles indicating the expectation to develop competencies related to the self and to relationships with others as well as understanding how to function in organizations and how to do social science research (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Competencies of the Andrews Leadership Program Since 2006.

Holistic Development

Another characteristic of the Leadership Program at Andrews is the combining of self-development and other leadership competencies into one whole, focusing on outcomes that include mental, physical and spiritual wholeness. When Alaby (2002) interviewed participants of the program, he found that one of the outcomes of the Leadership Program was “integrated, whole people.” This emphasis on the importance of developing the “whole” being, which has been part of the educational tradition of Andrews from its early days, is captured by Paul in 1 Thess. 5:23 (NASB): “Now may the God of peace Himself sanctify you entirely: and may your spirit and soul and body be preserved complete, without blame at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.” One of those educators involved in the 19th-century Battle Creek days of Andrews University says it this way:

True education means more than the pursual of a certain course of study. It means more than a preparation for the life that now is. It has to do with the whole being, and with the whole period of existence possible to man. It is the harmonious development of the physical, the mental, and the spiritual powers. (White, 1903, p. 13)

Education and leadership development are often concerned with mental aspects, but we also emphasize the physical and spiritual components of the whole self. We strive for harmonious development but recognize that we often fall short of attaining this goal. The development of the holistic approach has changed and grown over time. For instance, the original set of competencies didn’t name spiritual aspects specifically but addressed them in the “foundations” competency dealing with philosophical assumptions and worldview issues impacting leaders. When two Christian leaders, in an attempt to bring a focus on spirituality into their competencies, “rewrote” the competency list to include competencies that dealt with the spiritual aspects of Christian leadership, others soon followed. In 2006 the requirements for competencies were revised to include a competency called, “Ethics, Values and Spirituality.” Current leadership literature is unapologetic about including spirituality in leadership discussions (Burke, 2006; Dent, Higgins, & Wharff, 2005; Fairholm & Fairholm, 2009; Fry, 2003); however, this is generally a spirituality without mention of God, the creator of all things. We recognize this as a gap that Christians involved in leadership development can help fill. The Leadership Program attempts to close that gap.

Another way to respond to the question “What can be taught and learned?” is to think about skills, knowledge and attitudes. In the original set of 20 competencies developed in 1994, the Andrews Leadership Program focused on having its participants develop skills in instruction, implementing change, organizational development, effective communication, and conducting research—to name only a few. Another set of competencies focused on developing a working knowledge of learning theories, educational foundations, theories of leadership, social systems, and educational technology. Within a very short time it became clear we had created a false dichotomy. We realized that skills should have a knowledge base undergirding them and that the knowledge competencies should be demonstrated with some practical application in order to be of real value. As participants developed their competencies, they demonstrated the interplay between theory and practice. Thus, when the competencies were revised in 2006, the list was reduced to 15 and each was stated with the expectation that it would contain both theory (knowledge) and practice (skills) components.

Grint (2007) indicates that the recognition of the interplay between knowledge and skills has a long history. Aristotle uses the notions of techné, episteme and phronesis in his Nicomachean Ethics (Aristotle, trans. 1953).. We will talk about techné and episteme here, but will return to phronesis—the notion of wisdom—later on in the article. Techné refers to skills or “knowing how” to produce something. Leaders may need to know how to speak publicly or manage finances and these task-specific skills can be taught. But “the critical issue is that ‘knowing how’ may be enough for the current task but may not be enough for the completion of the next raft of tasks because completion may require the leader to understand why there is a problem in the first place” (Grint, 2007, p. 235). This second category of Aristotle, episteme or “knowing why,” is close to our notions of scientific knowledge or academic understandings.

This connection between knowing how and knowing why was a major focus of Alaby’s (2002) dissertation on the Andrews Leadership Program. In this study he describes what he calls the theory-practice paradox as representing the epistemological activity of the program participants—in other words, how participants come to “know” what they know. He finds that “the ‘job-embedded’ and ‘competency-based’ components encompass the practice pole, and the faculty support and academic credibility—based on theoretical proofs of 20 competencies— encompass the theory pole” (p. 202). In other words, participants are led to integrate the knowing why with the knowing how. Relying on either a skills-based or a knowledge-based approach to leadership development alone is a mistake, since both are approaches that begin by somehow blaming those who are deficient—lacking in skills and knowledge (Grint, 2007).

Moreover, there is another dimension which needs to be attended when educating leaders: context. “Leadership cannot be treated as though it were a portable set of knowledge, skills and attitudes; what works in one context may be conspicuously unsuccessful in another” (Mole, 2004, p. 129). In fact, employers recognize that receiving A’s throughout an academic program does not guarantee superior job performance. It is for this reason that programs have moved more and more “toward understanding and practicing leadership development more effectively in the context of the work itself” (p. 586). The Andrews Leadership Program has put in place the job-embeddedness requirement for all students—which seems to be a positive aspect of the program.

Narrative Modes of Learning

Bruner (1996) identified another concept around the acquisition of knowledge and related to the question of what can be taught and learned:

There appear to be two broad ways in which human beings organize and manage their knowledge of the world, indeed structure even their immediate experience: one seems more specialized for treating of physical ‘things,’ the other for treating of people and their plights. These are conventionally known as logical-scientific thinking and narrative thinking. (p. 39)

Education has tended to favor the logical-scientific mode, especially in modern times. However, in the past 30 years discussions around narrative have expanded exponentially in “narrative psychology,” “narrative research,” “narrative theology,” and “narrative criticism,” creating a substantially different way of approaching knowledge. A search using the key words “narrative” and “knowing” in Sage Publications shows 506 articles in the 1980s, 1,639 in the 1990s, and 6,869 between 2000 and 2009. Gubrium & Holstein (2009) point out that in today’s world “there are more stories, told in more circumstances, about an increasing number of topics” (p. 228). Leadership seems an ideal field for learning through developing narratives—this is, after all, what leaders do. They make meaning of their experiences through the stories they tell—of triumph, of failure, and of difficult journeys.

Narrative became a significant component of the Andrews Leadership Program following a 1996 research sabbatical by one faculty member to study with Jean Clandinin at the University of Alberta. The opportunity to observe the impact of an instructional strategy and research method that embraced narrative opened the door for the Leadership Program to include narratives as part of the individual development process. One of the requirements of the program is to write an “Individualized Development Plan” (IDP)—currently titled a “Leadership and Learning Plan” (LLP). In the first part of the IDP, initially called the “Vision Statement,” participants develop a vision of their life and work and take stock of their life journey. Because this vision statement is one of the key tools to motivate leaders to grow and change (Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, 2002), it is taught during the orientation week of the program. It was during such teaching for the 1997 cohort that we began to ask participants to recall “family stories,” “school stories,” “leadership stories,” and “change stories” as part of their vision statement development. Soon there was a strong sense that our core values are embedded in our narratives—and it is our values that drive our vision as human beings and as leaders.

That first section of the IDP is now called the “Vision Narrative” as we attempt to communicate what we hope this narrative will achieve for our participants. As we encouraged participants to read seminal books on narrative (Coles, 1989; Denning, 2005; Gabriel, 2000; Palmer, 2000; Polkinghorne, 1988; Simmons, 2006), we also learned that some individuals and some cultures are more amenable to personal storytelling than others. However, we have continued to embrace narratives in the program in spite of occasional difficulties. One faculty member observed, “I don’t know why it works, but it does and we need to keep including this aspect in our program.” This highlights the reality that we don’t always understand why we choose the strategies we use—we are learning what works through trial and error, through feeling our way—and the process is often messy.

Almost immediately following the introduction of narrative ways of knowing in the Andrews Leadership Program, participants began using narrative inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000) in their dissertations (Aufderhar, 2010; Barzee, 2008; Dove, 2003; Greene, 1998; Horn, 2005; Reyes 2010; Rouse, 2009). It is difficult to actually track the impact these dissertations had on the development of the Leadership Program as it is practiced at Andrews today. However, those involved in these dissertations assert that their understanding of narrative modes of learning and research has deepened. Horn’s (2005) dissertation is noteworthy because it focused specifically on the leadership development of Christian leaders in China. He found that “suffering” played an important role in shaping the leaders in his study. Understanding this finding helped faculty members relate in more meaningful ways to participants who were experiencing suffering and sharing stories of suffering. Once suffering was named by Horn as a “leader-shaping process” (Clinton, 1988), we began to see it in our own work. This is a large part of the power of narrative—it allows us to see through the stories of others truths that are difficult to relate by any other method.

According to Bruner (1996), “it is only in the narrative mode that one can construct an identity and find a place in one’s culture” (p. 42). With an increasing emphasis on “authentic leadership” (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, & Walumbwa, 2005; Shamir & Eilam, 2005), we are beginning to understand why it is important to pay attention to identity as part of what happens when individual stories are told and why stories are important for leadership development. Leaders need to understand who they are—and they achieve this understanding in part by learning the significance of their own life stories.

Absolute and Contextual Knowing

Another concept informing teaching and learning in the Leadership Program is intellectual development. On this topic, the works of Perry (1970), Baxter Magolda (1992), and Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule (1996) have been particularly informative. Perry’s work focused on the development of men, Belenky et al.’s work on women’s development, and Baxter Magolda’s research on both men and women; yet all three studies found that developmentally people tend to move from some form of “absolute knowing” to “contextual knowing.” For the purpose of discussion here, we will use Baxter Magolda’s (1992) categories. Students using an “absolute” way of knowing expected they would receive knowledge from their teachers and that their teachers would help them understand knowledge. They viewed knowledge as certain and absolute. As the students moved through “transitional knowing” to “independent knowing” and finally to “contextual knowing,” their ideas about the roles of students and teachers changed—and so did their conceptions of the nature of knowledge itself. A contextual knower integrates and applies knowledge and expects the teacher to promote discussion about various perspectives rather than handing down absolute truth.

Antonacopoulou & Bento (2004) point to differences between instructor-centered approaches and learner-centered approaches—the former being a more traditional approach to education where the transmission of knowledge is the objective. They state that “while they [traditional approaches to teaching leadership] might be useful in transmitting knowledge about leadership, they stop short at developing leadership per se” (p. 81).

The faculty members involved in the Leadership Program at Andrews have consistently embraced a learner-centered approach to the program. We believe our work is to develop “thinkers and not mere reflectors of other men’s thoughts” (White, 1903, p. 17). Participants are always arranged in groups during the week-long orientation to facilitate dialogue and interaction. When we feel compelled to provide “information” in the form of lectures, we try to encourage discussion and application of this information. The fact that we call ourselves—faculty and students alike—“participants” suggests that the faculty do not see themselves as “experts” whose task is to provide information to passive recipients. Instead, the faculty see themselves participating in the learning process along with everyone enrolled in the program.

Because the Leadership Program at Andrews is a graduate program, and requires participants to be currently employed and to have at least five years of work experience, one would assume that most participants have moved away from received forms of knowledge. However, the educational process and the various cultural backgrounds from which participants come can result in strong expectations that teachers will provide knowledge. When we don’t meet this expectation, asking all participants instead to be part of developing and creating knowledge, the experience creates ambiguity for many—often at a slightly uncomfortable level. Participants looking back at their first exposure to the program sometimes affectionately refer to the orientation as “disorientation.” Yet, as they move through this stage they begin to develop more complex ways of viewing their world and work that ultimately enable them to lead more effectively in the often disorienting contexts of their own organizations.

If it is true that leadership development includes a focus on self as well as relationships with others, a seeking of skills, knowledge and practical wisdom, and is mediated by narrative knowing and learning in context, how do leaders actually learn? We have already pointed out that the program may be hindered or helped in the real leadership development we are trying to foster, depending on the expectations and experiences our participants bring to the program. We now turn to more specific focus on learning and learning theories to help describe the approach used by the Andrews program.

Learning Theories

Ideas related to learning have created some conflict in the Andrews program over the years. When the first cohort was introduced to a group of competencies that included the knowledge of “learning theories” and skills as an “effective teacher/instructor,” some participants resisted this emphasis on what they considered educational jargon and an emphasis on teaching. The faculty initially responded by redefining the instructional competencies to emphasize “mentoring” instead of teaching and instruction—a concept that is applicable in most professional situations. But as participants started to present their portfolios it became clear that leadership and learning have a very close relationship. Antonacopoulou & Bento (2004) say it this way: “Leadership is not taught and leadership is not learned. Leadership is learning. . . . In this sense, the crucial question in leadership development is not just what to learn, but how to learn how to learn” (p. 82). More recently the organizational change expert Fullan (2008) has insisted that “you can achieve consistency and innovation only through deep and consistent learning in context” (p. 86) and that there should be a “critical mass of organizational colleagues who are indeed learners” (p. 110). As organizations compete to thrive in the market place, “leaders who keep learning may be the ultimate source of sustainable competitive advantage” (Fulmer, Gibbs, & Goldsmith, 2000, p. 49).

Thus learning continued to be a core element of the Leadership Program. When the list of competencies was redeveloped in 2006, one of the competencies related to self-development was named “Learning and Human Development” and the IDP was renamed the Leadership and Learning Plan (LLP)—thus emphasizing the relationship between leadership and learning. Later, regional groups were renamed Leadership and Learning Groups (LLGs) to acknowledge that increased technology was making it possible for people to connect regardless of geographic location but that learning was the key focus of the groups.

As the program expanded to international sites, the conversations around the concept of “learning” took on additional dimensions because of the way the word is perceived in some countries. Learning in some cultures is more instructor-centered. For people who have developed this conception of learning, it took a great deal of dialogue to reach a common understanding about expectations, perceptions, and goals. These conversations not only forced us to think about the meaning of the word “learning” in different cultural contexts, but also caused us to wonder whether we really wanted to emphasize the idea or use the word at all.

Experiential Learning & Reflection

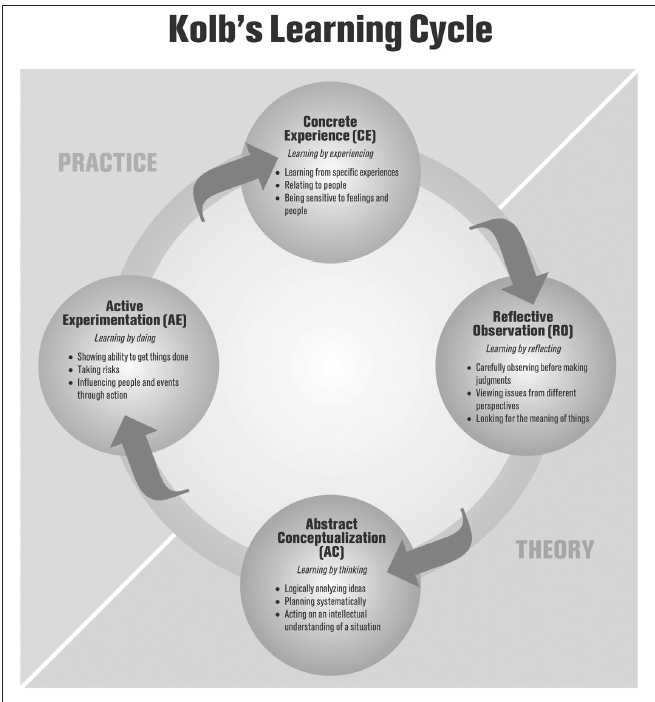

In spite of these questions and uncertainties, we realize that we have made use of several theories to guide us in developing leaders from different walks of life and work. One of them has been Kolb’s experiential learning theory (Kolb, 1984). Based on the Lewinian Experiential Learning Model, it portrays learning as a cycle that moves from “concrete experience” to “observations and reflections” to “formation of abstract concepts and generalizations” and finally to “testing implications of concepts in new situations” (p. 21). It is not surprising, with the emphasis on job-embedded learning, that the faculty would embrace an experiential learning theory.

This theory has also been helpful in answering how the program can be a Ph.D. program while including such a strong focus on practice and experimentation. Often the faculty use the learning cycle with a line drawn through it diagonally to emphasize practice (concrete experience and experimentation/application) and theory (reflection and abstract theorizing) and to point out that in graduate programs academics often make a distinction between “professional programs,” those focused on practical matters, and “academic programs,” those focused more heavily on theory or the thinking part of learning (see Figure 2). We like to emphasize that the Leadership Program is both a professional program— because it is job-embedded—and an academic program—because of the expectation that practice will be linked with theory through reflection and research.

Since reflection is so central to the learning cycle, it is important to dwell for a moment on the question, What is reflection? To answer this question, we first note that in Kolb’s learning cycle, reflection is located

Figure 2. The Experiential Learning Cycle Based on Kolb (1984).

Figure 2. The Experiential Learning Cycle Based on Kolb (1984).

between “concrete experiences” and “abstract theorizing.” This juxtaposition provides a visual way to depict reflection as connecting theory and practice. We often talk about how it is reflection that pulls together the concrete experience with abstract theories.

More specific definitions of reflection have been developed by educators like Dewey (1933), Schön (1983), Kolb (1984), Boud, Keogh, and Walker (1985), Mezirow (2000) and others. Yet Procee (2006) points out “that the huge amount of literature in this field highlights the lack of conceptual clarity that exists” (p. 252). He notes that there is a difference between reflectivity and reflection with Kolb, Schön, and Dewey closely aligned with reflectivity, and Mezirow with reflection, whereas Boud, Keough, and Walker combine both traditions. We have not been particularly aware of these differences; however, we have noted the pyramid developed by Yorks and Marsick (2000) showing different levels of reflection from incidental reflection to content, process and premise reflection. Their work was based on the dissertation work of O’Neil (1999), who identified four theoretical schools and the type of reflection associated with them: the tacit school (incidental reflection), the scientific school (content reflection), Kolb’s experiential school (content and process reflection), and Mezirow’s critical reflection school (content, process and premise reflection).

In the early stages of the Leadership Program, the focus of reflection was more incidental, if it existed at all. When the program began in 1994 it was only hinted at in the research competency, which stated that an Andrews Leadership graduate would be “a reflective researcher” with skills in reading and evaluating research, conducting research, and reporting research. In 2002 Alaby described the importance of reflection in the program and named “critical reflection” as the process whereby the opposing poles of theory and practice could be brought together. He also noted that critical reflection would bring together the opposing ideas of individual work and community learning. He didn’t show evidence of critical reflection in the program itself in his interviews with participants, but rather asked questions such as “Does AU provide a ‘space’ where such reflective practice can occur? Do the faculty have opportunities to reflect on their practice?” (p. 122). As the importance of reflection became clearer, the program participants began to talk about making connections between theory and practice in reflection papers and the faculty developed a rubric to help describe how to best approach this complex task. This has sparked substantial conversation around the concept of reflection as it is portrayed in the rubric (see Figure 3).

|

5 Exceptional |

4 Proficient (Target) |

3 Satisfactory |

2 Emerging |

1 Unsatisfactory |

|

| Content & | Makes relevant | Topics relevant to | Topics generally | Topics somewhat | Topics not relevant |

| Organization | connections to | competency; care- | relevant to compe- | relevant to compe- | to competency; |

| multiple competen- | fully focused; well | tency; logically | tency; poorly | lacks focus and | |

| cies; excellent pres- | organized; sound | arranged; adequately | focused; organiza- | organization; | |

| entation of ideas; | scholarly argument | organized to express | tion restricts com- | content may be | |

| insightful | desired concepts | prehensibility | plagiarized | ||

| Knowledge Base | Evidence of a broad, | Evidence of synthe- | Evidence of | Evidence of com- | Little or no evidence |

| carefully evaluated | sis of an expanding | analysis of a well- | prehension of a | of knowledge base | |

| knowledge base | know¬ledge base | documented | narrow knowledge | ||

| which includes | which includes | knowledge base | base | ||

| synthesis of multi- | analysis of theoreti- | ||||

| ple theoretical | cal perspectives | ||||

| perspectives | |||||

| Reflection | Evidence of new | Evidence of | Multiple rich exam- | Some examples | No evidence of |

| (integration of | practice based on | improved practice | ples of integration | of integration of | integration of |

| knowledge base | integration of | based on integra- | of knowledge base | knowledge base | knowledge base |

| with practice) | knowledge base | tion of knowledge | with practice | with practice | with practice |

| with practice | base with practice |

Figure 3. Rubric for reflection papers used in the Andrews Leadership Program.

Thirteen years after the program began, Rausch (2007) determined that “reflection allowed the participants to move beyond descriptive accounts to analyze, interrelate, and synthesize their various experiences in relation to their learning” (p. 103). He found evidence of reflection in leadership participants’ portfolios and concluded that “portfolio development can result in authentic experiential learning when accompanied by reflective analysis that weaves the richness of the experience with a theoretical knowledge base” (p. 103). However, it was in the actual presentation of the portfolio where participants referred more to their changing perspectives (Mezirow & Associates, 1990). This finding indicates that some participants are moving beyond Kolb’s notions of reflection to more critical reflective behavior where perspectives and assumptions are challenged and documented. It may be time for the program participants to review the reflection paper rubric and move intentionally towards more critical forms of reflection and the challenging of perspectives (Mezirow & Associates, 1990).

Besides Rausch’s (2007) dissertation, two other dissertations by Leadership graduates have had an impact on our thinking about reflection. MacDonald (2003) used the Reflective Judgment Model (King & Kitchener, 1994) to describe the levels of reflection of public school administrators. Some of her findings are especially relevant to this article. She found a great deal of variability in levels of reflection, and a positive relationship between age and internships and reflective judgment. Interestingly, she also found that the number of leadership courses had a negative effect. She concluded that “teachers in Educational Leadership Programs should have a good understanding of the reflective judgment developmental process, know how to assess it properly, and then be able to provide appropriate interventions and opportunities to enhance students’ reasoning abilities” (p. 148).

These were intriguing findings, indicating a connection between levels of reflection and specific pedagogical practices (internship and classes). But in the Leadership Program we were faced with a different need that led us to emphasize not so much the element of intervention but another element of learning which is emphasized by Procee (2006).

From a Kantian epistemology another insight also arises. It makes clear that judgment is a much more intricate concept than can be captured by a simple linear model of successive phases. . . . A specific problem with such models is their orientation toward improvement. Psychologically, such a view implies that the learner must take a negative attitude toward his or her past performances. That negative orientation may have the effect of instilling in students an aversion to reflection. . . . The Kantian epistemology is emotionally less burdensome because it emphasizes the making of discoveries (in the field of specialization, in the persons themselves, in the wider social world) (p. 250).

This same emphasis has led the faculty to be increasingly interested in focusing on strengths rather than deficiencies (Rath & Conchie, 2008), and our notions of reflection have tended to focus simply on making connections between theory and practice.

A second study focusing on reflection was done by Van Horn (1999), who used reflective journals and dialogue in her nursing clinical. She developed a rating rubric (from Boud et al., 1985) to measure levels of reflection and found that journaling and dialogue significantly increased the levels of reflection for nurses in their clinical experience and thus the quality of decision making. While her study was not directly related to the Andrews Leadership Program, at least three of her committee members were on the faculty and there is no doubt that her literature and findings influenced and excited those faculty members.

How is reflection facilitated in the Leadership Program? We believe reflection happens primarily through dialogue and writing. Two program “structures” that facilitate this process are the reflection papers required for the portfolio and participation in Leadership and Learning Groups. Since the inception of the program, participants have been required to meet in groups when they are away from Andrews. These groups review one another’s competencies and provide emotional, relational, and learning support as they complete the journey through their graduate program. Taylor (2007) notes that “inherent in relationships, is the engagement in dialogue with others, which is also seen as essential to transformative learning in general” (p. 179). This brings us back to Mezirow’s theory of transformation—learning through critical reflection and transformative learning. While Taylor (2007) points out that “it is through trustful relationships that allow individuals to have questioning discussions, share information openly and achieve mutual and consensual understanding” (p. 179), he also asserts that not much is known about these kinds of relationships.

We would agree that our understanding of our group process is still limited. What we do know is that when the group process works, participants make good progress in the program and are pleased with their learning. However, we also know that when groups do not work well, the results can be devastating in terms of progress and learning. Referring back to our earlier discussion of ways of knowing, it is possible that it is difficult to establish a functioning group where dialogue takes place regularly if group members don’t see the value of discussion. The contextual knower (Baxter Magolda, 1992) expects to enhance the learning via quality contributions, whereas absolute knowers may find it difficult to engage in meaningful dialogue.

Social Constructivism

This brings us to another theory that has travelled well with the Leadership Program—social constructivism (Bruner, 1996; Dewey, 1916; Vygotsky, 1978). This theory comes from the realization that something more than simple transmission models of education are needed—that learners really do have to construct their own meanings and that this often happens in dialogue with other learners (Isaacs, 1999). Combined with Mezirow’s (2000) transformational learning theory, we have a plausible explanation of what happens in functioning study groups—participants do challenge one another’s assumptions about how the world works and, in the process, deepen their own understandings. Parker and Carroll (2009) state that “the transformative potential of the constructivist process of working with a peer emanates from the attention to process that facilitates deeper understanding of self and others” (p. 267). However, in our program the community aspects of learning are in tension with the individual aspects (Alaby, 2002, pp. 130-148).

The importance of individual development was highlighted in the earlier discussion about the differences between leader development and leadership development. Day (2001) summarizes the differences between the two and lists the following skills that need to be developed within the individual: emotional awareness, self confidence, accurate self image, self-control, trustworthiness, personal responsibility, adaptability, initiative, commitment and optimism (p. 584). There is an individual work to be done, and in the Andrews program this is accomplished mainly through the opportunities participants have to make choices regarding their learning. They are able to choose what they will write in their IDP’s, which projects they will focus on, which books and articles they will read, which artifacts will go into their portfolios and, in many instances, how they will learn and what they will learn. The notions of “individual development” and “choice” fit well with who we are as Christians. Jesus responded to people individually, such as Nicodemus (John 3) and the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4). And clearly, God gives His people choice. “Choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve.” (Josh. 24:15; see also Dt. 39:19, Prov. 16:16, John 15:16). White (1903) points out that this power of choice is the creator’s gift to humans:

God might have created them (Adam and Eve) without the power to transgress His requirements, but in that case there could have been no development of character; their service would not have been voluntary, but forced. Therefore He gave them the power of choice—the power to yield or to withhold obedience. (p. 23)

As painful as it is for many participants—especially received knowers—to be in a space where the expectation is that they will make choices regarding their own learning, we continue to observe that the depth of their learning is directly connected to their willingness to make these kinds of choices. As leadership development facilitators we often revisit the idea of choice. Sometimes it would be easier for us simply to make decisions about exactly what is expected, but we remind ourselves that if we do, we will likely be limiting the leadership development of our participants.

The Development of Practical Wisdom in Leaders

And so we return to Aristotle’s advice to his son Nicomacheus and his three kinds of knowledge: techné (know how), episteme (know why) and phronesis (knowing when). There is evidence that techné (skills) and episteme (scholarly knowledge) are embedded in the Leadership Program, but what about phronesis (practical wisdom)? What is it and how is it evident in our leadership development at Andrews?

Several authors suggest that phronesis is directly connected to action in particular situations (Grint, 2007; Halverson, 2004; Parker & Carroll, 2009). Grint (2007) says that “it is essentially rooted in action rather than simply reflection. It is something intimately bound up with lived experience rather than abstract reason (episteme) but it is not a set of techniques to be deployed (techné)” (p. 236). Halverson (2004) adds the following:

Phronesis is the experiential knowledge, embedded in character, used by individuals to determine and follow courses of intentional action. Phronesis is an essentially moral form of knowledge, guided by the habits of virtue that come to form character. . . . Phronesis provides a kind of executive function, resulting from habitual action and embedded in character, that helps leaders determine which techniques we will (and can) use, which theories are appropriate, and what are the significant consequences of our actions. . . . The aim of phronesis is not to develop rules or techniques true for all circumstances, but to adjust knowledge to the peculiarity of local circumstance. (pp. 92-93)

This ability is not easy to develop because it requires a willingness to go beyond experiential and beyond mere rational knowing. Hedges (2008) maintains the following:

Knowledge is not wisdom. Knowledge is the domain of scientific and intellectual inquiry. Wisdom goes beyond self-awareness. It permits us to interpret the rational and the nonrational. It is both intellectual and intuitive. And those who remain trapped within the confines of knowledge and pedantry do not commune with the larger world. They cannot see or speak to the deeper truths of life. (p. 162)

Blomberg (1997) sees “wisdom” as an escape through the horns of a dilemma, and the dilemma he is concerned about is the theory-practice dilemma. He points out the difference between the Greek and Hebrew minds: The Greek mind seeks to understand the world by standing apart from it—on great theatrical stages—whereas the Hebrew mind understands life by living it. He points out that “the Greek word for ‘theatre’ also gives us the word ‘theory’: it is as a spectator, contemplating at a distance what is going on rather than immersing myself in the action, that will enable me to see the truth” (p. 121). He goes on to assert that “rather than expecting certainty, the Hebrews were convinced of the continually ambivalent and puzzling nature of events” (p. 125).

It seems that wisdom comes through ambivalent and puzzling experiences in which the individual learns which action to take. Chia and Holt (2007) make clear that “wisdom is not about having more information or constructing irrefutable propositions. True wisdom exceeds these quantifiable elements. It takes its cue from vagueness and ambiguity” (p. 505). Grint (2007) makes this conclusion about phronesis:

Phronesis, then, is not a method, and it cannot be reduced to a set of rules because it is dependent upon the situation and there is, therefore, no meta-narrative to guide the process. . . . For this reason, phronesis cannot be taught in any lecture theatre but must be lived through. (p. 242)

Where does the Leadership Program provide a learning space to develop this kind of wisdom? A place to start is the fact that all participants are full-time leaders in their organizations. It is assumed that the job-embedded nature of the Leadership Program provides one place in which participants are able to take action in particular situations that are fraught with ambiguity and uncertainty. In addition, within the program itself, there are components that create ambiguity—concepts that exist in tension with one another: theory-practice, individual-community, choice-requirements, received knowledge-contextual knowledge, reflectivity-reflection, leader-leadership. These elements can be viewed in opposition to one another and participants often show frustration as they try to make meaning of them. How does one live and make meaning through two ideas that seem like polar opposites but are both necessary and true? We suggest this happens only through wisdom. Blomberg (1997) notes that in the book of Job there was a

“crisis of wisdom,” when an openness to puzzlement had hardened into a rigid interpretation of the world as a virtually closed system of cause and effect, a set of principles that could be universally applied without sensitivity to the particular situation. (p. 126)

It may be that in learning to live through the inherent dichotomies of the program, participants develop wisdom—an ability to take action in particular contexts in which there are no clear or straight-forward answers. In the early days of the program we talked a lot about the need for our participants to have a “tolerance for ambiguity.” Through wisdom these dilemmas generate opportunity for actions and so they come to be viewed as a “unity” of some sort. Practitioners find help as they develop a theory of action to undergird their actions, and the book wise learn to test new insights in real life situations. But all of them are nudged to choose appropriate aspects of theory and/or practice to utilize in making wise decisions.

Likewise, the participant must sort through issues related to the individual and community aspects of the program. Personal choice and program requirements also create some tension and ambiguity. People often ask how we can simultaneously embrace “choice” (for instance, participants write their own course of study) and still have program requirements. As participants embrace these tensions they not only develop their own unique path to program completion, but they also seem to grow in their capacity for leadership. Often experienced leaders, used to being voices of authority in their own contexts, learn to listen to the penetrating questions of fellow participants and walk away challenged in their assumptions about reality and with new insights to be tested.

Procee (2006) concludes that reflection in Kantian epistemology “is not just comparing, but also holding together—bringing forward a nonal- gorithmic unity or a new insight” (p. 251). He states that “the basic idea of Kantian epistemology is the tripartite model of concept (understanding), field of in betweenness (judgment), and domains in reality (experience)” (p. 251). It seems to us that Kant’s idea of reflective judgment, which is similar to Aristotle’s phronesis, comes close to the reality of the world of change and dynamic chaos many leaders face on a daily basis. For this reason wisdom cannot be viewed only as action taking through the horns of dilemmas. Actions are taken because of an individual’s character and moral and ethical knowledge (Halverson, 2004). There is a rather vast literature concerning morality and ethics, but Blomberg (1997) provides insight on what this means for Christians:

This openness to the particular situation or event, to the contingent, to what happens but need not necessarily happen, flows from the biblical teaching on creation. Each creature is made and loved by God, with its own unique characteristics. Wisdom means being sensitive to this uniqueness, treating all things as ends in themselves and not merely as means to ends. Contrary to the bureaucratic mentality that would deal with each case in terms of the application of predetermined rules, wisdom seeks what is best for this creature in this place at this time . . . . Wisdom is just action, action that is in accord with God’s purposes and responsive to the guidance of his Spirit, for the order of the world is justice, what is right or righteous. There is no place for relativism, but there is a premium on standing in the right relation to things. (p. 126)

White (1911) further clarifies: “To deal wisely with different classes of minds, under varied circumstances and conditions, is a work requiring wisdom and judgment enlightened and sanctified by the Spirit of God” (p. 386). The Proverbs are clear about the source of wisdom: “For the Lord giveth wisdom: out of his mouth cometh knowledge and understanding” (Prov. 2:6. See also Prov. 4:7; 9:10; 11:2; 15:33; and 1 Cor. 1:18- 30). Christians understand that not only does God create each one in a unique way (Ps. 139), but He also provides the experiences that shape our haracters, when we trust Him with our lives.

Thus a Christian perspective of leadership development includes a focus on skills and knowledge, but also embraces the dimension of wisdom because it provides a way through the dilemmas of contradictory concepts and ambiguities created by times of change. In addition, wisdom calls us to also focus on the moral aspects of the particular situation. Blomberg (1997) gives this reminder:

Daily life presents us, as it did Job and his friends, with messy, ill- structured problems. The Greek mind cannot live with messiness: everything must be rationalized. The biblical mind revels in creation’s fecundity and accepts the challenge of bringing healing where there is brokenness. (p. 133)

Finally, “In order to learn phronesis, we must be able to see it in action” (Halverson, 2004, p. 94). This places a formidable burden on those involved in leadership development. Modeling wisdom in the context of ambiguity means that sometimes leaders don’t get it right. That is also true in our program. We understand clearly that we may not always get it right. This recognition has led us to begin to see the role of forgiveness in leadership in a new light. While there is some academic literature about forgiveness in leadership (Ferch & Mitchell, 2001), again, as in spirituality, it is a forgiveness without a focus on God. Maybe is an opportunity for Christians to be active in developing God-acknowledging theory and practices that will inform leadership development programs. Time will tell how this aspect will fit into our Andrews program.

Ongoing Questions

This article has reviewed a dynamic, community-connected view of leadership development. We realize that moving away from static views of leadership development as merely the accumulation of knowledge and skills is not an easy task. Knowledge and skill development are important and necessary—but they are insufficient for the leadership our communities need in the twenty-first century. We believe staying community- embedded and learning-focused is crucial to helping create holistic views of leadership that build up our schools, churches, businesses and communities. The more we, in our Andrews University Leadership Program, learn with leaders, the more we have grown to appreciate the peace and joy that comes from shared dynamics and mutual respect. We believe this approach breathes both choice and voice into the tension-filled world of leading. We have seen and experienced ourselves the life-changing, God- affirming, wisdom-producing experiences and opportunities such a view creates. Both leaders and followers experience leadership—both the formal teacher and the formal learner share in learning. To use a common metaphor, the whole sea is raised and more boats are floated.

But all this comes at some cost. Learning is not easy and is never finished. One has to work through old and outdated paradigms, strive for healthier group dynamics, and usually help those who want to lead remember that they don’t have to do it alone. This taps deeply into the understanding of the “body of Christ” as a community of believers. Shifting from authoritative and sometimes restrictive views of leadership to this view can involve personal pain, frustrations, and doubts. But, as we have shown, that is the stuff that makes wisdom.

We can’t end this paper with conclusive statements because we have learned how much of our own knowledge is emerging. We have learned that our best growth is where we still have tensions and questions—and we have many. Here are some of them:

- What kinds of research skills, knowledge and experience best serve our model of leadership? The twenty-first century has given us a massive array of tools to handle and interpret information and to lead organizations. Because we are housed in academic environments, we insist on the importance of research-based knowledge and skill development in leadership development. Precision of thought, skepticism that promotes inquiry, and methodological procedures that improve truth discovery are all essential in wisdom development and the processes by which leaders makes sense of their world. However, some of the more traditional approaches to research we have encountered have not always been sensitive to the embedded nature of leadership research. Collaborative research in which the researcher learns with her subjects or community has often been viewed as biasing, unethical, and less than accurate. However, more embedded learning is precisely what we believe leaders need to know about to be data-driven decision makers. We still wrestle with how to give leaders experience in action research, embedded meaning, and interpretive qualitative research techniques while not diminishing the traditional laboratory, double-blind experimental approach to knowledge.

- How can a transformational model work in the context of transmis- sion-focused education? We have emphasized the transformational dynamic of learning essential for developing leadership. However, we work in educational contexts were transmission-based learning is still the dominant way. We do not want to send the message that we reject the need for transmission-based learning in leadership development. For about seven years, the Andrews Leadership Program has benefitted from being in the same department as traditional educational administration training programs (K-12 and higher education). This proximity has created challenges. One program has tight accreditation demands for certain skills, knowledge and subjects to be covered, which has led to the need for more rigid programs of leadership development. We have resisted that drift towards more rigidity for the Leadership Program to allow more choice and voice. However, the structure of the administration programs has given our leadership participants the option to also make use of more traditional transmission learning in our online courses.

So, how can transmission and transitional learning work together better? We keep trying to learn and, as with most of our learning, we learn with our participant leaders. One of our recent leadership graduates, Janine Lim, put forward an insightful approach to the integration between these two types of learning in her concluding program paper:

Learning is based on conversation and interaction, on sharing, creating and participation, and is embedded in meaningful activities such as collaborative work (Downes, 2006). Connective learning includes the concept that knowledge is stored in your network of knowledge sources instead of one person trying to “know everything” (Tracey, 2009, March 17). A person stores knowledge in people within their network or within networked resources.

A critical response to this theory suggests that connectivism isn’t the only way to learn. Instructivism is still alive and well because it is efficient. Sometimes specific knowledge is required and must be passed on quickly (Tracey, 2009, March 17). Tracey suggests that the three types of learning, instructivism, constructivism and connectivism are complementary and required at different times and in different learning scenarios. Each type of learning has its place. (Lim, 2010, p. 16, italics added)

As we have increased the offering of online courses and looked for more structured learning opportunities, some of the earlier participants have been wondering if this represents “course creep,” the move away from choice and individuality toward more traditional and specific learning requirements. We wonder too. But then, such is the nature of change and growth. Today participants have access to online videos, instructional DVD’s, and online resources to facilitate transmission. They are not intended to take the place of the synergy of social learning. We anticipate that wisdom will continue to need to grow in understanding how instructivist, constructivist and connectivist learning can be merged into overall development.

- Will this model of leadership development work with less-experienced leaders? For 16 years our program has been working with experienced and employed individuals who not only have track records in management or leadership positions, but have the benefit of significant growth from sustained employment. There is nothing like work to develop leadership. So we have wondered if this socially embedded, learning-based model of leadership development would work with younger individuals in their teens who are high school and undergraduate college students. In 2007, Frances Faehner, a graduate of the program, finished her study of the feasibility and possible strategies of leadership development for undergraduates at Andrews University. This program is currently implemented and we are exploring what methods will work in this different context (see also the article by David Ferguson in this issue).

- What does this view of leadership say about educational reform?

We concur with Bruner (1996) that “pedagogy is never innocent” (p. 63). We believe the Andrews Leadership Program has some elements in it that facilitate reflection, wholeness, and transformation. How they all work together is not entirely clear. However, we are beginning to wonder how this experience in learning can inform calls for educational reform in the K-16 system. As standards are increasingly pressed down to younger and younger children, and the pedagogy becomes transmission rigid, we worry about our children (the leaders of tomorrow). They are struggling to memorize the accumulated facts—and there are a lot of them—and we wonder if they are being stunted in their own approach to inquisitive learning. Can you really develop if all your thinking is done for you and the answers are passed on without a call to question, reflect and apply? How are they learning to learn? What is happening to their love of learning—their joy?

This love of learning is a gift the Creator has endowed us with not only for this life, but also for the life to come. It is part of the hope we share with fellow Christian leaders. God fully intends His children to be learning now and through all eternity. One of the leaders instrumental in the development of Andrews University says it this way:

There [in the world to come] every power will be developed, every capability increased. The grandest enterprises will be carried for- ward, the loftiest aspirations will be reached, the highest ambitions realized. And still there will arise new heights to surmount, new wonders to admire, new truths to comprehend, fresh objects to call forth the powers of body and mind and soul. (White, 1903, p. 307, italics added).

References

Alaby, J. A. (2002). Means and ends of the Andrews University Leadership Program: A study of its critical components and outcomes as they relate to the mission statement. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (AAT 3058305)

Antonacopoulou, E. P., & Bento, R. F. (2004). Methods of “learning leadership”: Taught and experiential. In J. Storey (Ed.), Leadership in organizations: Current issues and key trends (pp. 80-102). London: Routledge.

Ardichvili, A., & Manderscheid, S. V. (2008). Emerging practices in leadership development: An introduction. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(5), 619-631. doi: 10.1177/1523422308321718

Aufderhar, M. J. (2010). Clergy family systems training and how it changes clergy leadership attitudes and practices. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI.

Avolio, B., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315-338. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001

Barzee, S. (2008). The schooling experiences and achievement of adolescent Black males: The voice of the students. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI.

Baxter Magolda, M. (1992). Knowing and reasoning in college. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Belenky, M., Clinchy, B., Goldberger, N. R., & Tarule, J. M. (1996). Women’s ways of knowing (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Blomberg, D. (1997). Wisdom at play: In the world but not of it. In I. Lambert & S. Mitchell (Eds.), The crumbling walls of certainty. Macquarie Centre, NSW, Australia: Macquarie University.

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Reflection: Turning experience into learning.

London: Kogan Page.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Burke, R. (2006). Leadership and spirituality. Foresight, 8(6), 14-25.

Chia, R., & Holt, R. (2007). Wisdom as learned ignorance. In E. Kessler & J. Bailey (Eds.),

Handbook of organizational and managerial wisdom (pp. 505-526). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Clandinin, J., & Connelly, F. (2000). Narrative inquiry. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Clinton, J. R. (1988). The making of a leader. Colorado Springs, CO: Navpress.

Coles, R. (1989). The call of stories. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Day, D. V. (2001). Leadership development: A review in context. Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581-613. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00061-8

Denning, S. (2005). The leader’s guide to storytelling: Mastering the art and discipline of business narrative. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dent, E. (n.d.). Researching leadership from a systems perspective: Observations and challenges. Retrieved March 17, 2010, from http://www.uncp.edu/home/dente/tman633/colombia.htm

Dent, E., Higgins, M., & Wharff, D. (2005). Spirituality and leadership: An empirical review of definitions, distinctions, and embedded assumptions. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 625-653. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.07.002

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: The Free Press.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston: D. C. Heath.

Dove, J. W. (2003). An autobiographical study of my beliefs, attributes, and practices as an instructional support consultant. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (AAT 3081068)

Downes, S. (2006). Learning networks and connective knowledge. Retrieved March 21, 2010, from http://it.coe.uga.edu/itforum/paper92/paper92.html

Drucker, P. F. (1995). Managing in a time of great change. New York: Truman Talley Books/Dutton.

Fairholm, M. R., & Fairholm, G. W. (2009). Understanding leadership perspectives. New York: Springer. Chapter 7, The spiritual heart of leadership, can be accessed online at doi:10.1007/978-0-387-84902-7_7

Ferch, S., & Mitchell, M. (2001). Intentional forgiveness in relationship leadership: A technique for enhancing effective leadership. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 7(70). doi: 10.1177/107179190100700406

Fry, L. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14, 693- 727. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.09.001

Fullan, M. (2008). The six secrets of change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fulmer, R. M., Gibbs, P. A., & Goldsmith, M. (2000). Developing leaders: How winning companies keep on winning. Sloan Management Review, 42(1), 49-59.

Gabriel, Y. (2000). Storytelling in organizations: Facts, fictions, and fantasies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R., & Walumbwa, F. (2005). “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 343-372. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.003

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2002). Primal leadership: Learning to lead with emotional intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Greene, G. (1998). A longitudinal study on the essence of success development as seen by Caribbean-Canadian women in the storied landscape of their lived experience. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI.

Greenleaf, R. (2002). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Grint, K. (2007). Learning to lead: Can Aristotle help us find the road to wisdom?

Leadership, 3(2), 231-246. doi: 10.1177/1742715007076215

Gubrium, J. F., & Holstein, J. (2009). Analyzing narrative reality. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Halverson, R. (2004). Accessing, documenting and communicating practical wisdom:

The phronesis of school leadership practice. American Journal of Education, 111(1), 90- 121. doi: 10.1086/424721

Hedges, C. (2008). I don’t believe in atheists. New York: Free Press.

Hewson, M. (2009). Leadership in turbulent times. Retrieved March 17, 2010, from http://www.lockheedmartin.com/news/speeches/100809-hewson.html

Horn, T. W., Jr. (2005). Developmental processes critical to the formation of servant leaders in China. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital (AAT 3196713) Dissertations.

Iles, P., & Preece, D. (2006). Developing leaders or developing leadership? The Academy of Chief Executives’ programmes in the North East of England. Leadership, 2(3), 317- 340. doi: 10.1177/1742715006066024

Isaacs, W. (1999). Dialogue and the art of thinking together. New York: Currency.

Jones, A. (2006). Leading questions: Developing what? An anthropological look at the leadership development process across cultures. Leadership, 2(4), 481-498. doi: 10.1177/1742715006068935

King, P., & Kitchener, K. (1994). Developing reflective judgment. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experimental learning: Experience as the source of learning and devel- opment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lim, J. (2010). A synthesis of my leadership journey. Unpublished paper, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI.

MacDonald, M. (2003). The contribution of education, experience, and personal characteristics on the reflective judgment of students preparing for school administration. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (AAT 3098158)

McCauley, C. D., & Van Velsor, E. (Eds.). (2004). The Center for Creative Leadership handbook of leadership develoment (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. New York: Wiley.

Mezirow, J., & Associates. (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformation and emancipatory learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mole, G. (2004). Can leadership be taught? In J. Storey (Ed.), Leadership in organizations: Current issues and key trends (pp. 125-137). London: Routledge.

O’Neil, J. (1999). The role of the learning advisor in action learning. Doctoral dissertation, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (AAT 9939533)

Palmer, P. (2000). Let your life speak: Listening for the voice of vocation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Parker, P., & Carroll, B. (2009). Leadership development: Insights from a careers perspective. Leadership, 5(2), 261, 262-284. doi: 10.1177/1742715009102940

Perry, W. G. J. (1970). Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years.

New York: Rinehart and Winston.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Procee, H. (2006). Reflection in education: A Kantian epistemology. Educational Theory, 56(3), 237-253.

Rath, T., & Conchie, B. (2008). Strengths-based leadership. New York: Gallup Press. Rausch, D. W. (2007). Demonstrating experiential learning at the graduate level using portfolio development and reflection. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (AAT 3289968)

Reyes, A. L. (2010). Intercultural relationships in organizational transformation: A single- case study of Baptist University of the Americas. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI.

Rouse, S. (2009). A Narrative case study describing the support culture for the change process in a small parochial, boarding secondary school. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books.

Shamir, B., & Eilam, G. (2005). What’s your story? A life-stories approach to authentic leadership development. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 395-417. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.005

Simmons, A. (2006). The story factor. New York: Basic Books.

Spears, L., Lawence, M., & Blanchard, K. (2001). Focus on leadership: Servant leadership for the 21st century (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Taylor, E. (2007). An update of transformative learning theory: A critical review of the empirical research (1999-2005). International Journal of Lifelong Education, 26(2), 173- 191. doi: 10.1080/02601370701219475

Tracey, R. (2009, March 17). Instructivism, constructivism or connectivism? Retrieved from http://ryan2point0.wordpress.com/

Vaill, P. (1996). Learning as a way of being: Strategies for survival in a world of permanent white water. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Van Horn, R. (1999). The reflective process in nursing clinicals using journaling and dialogue. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations. (AAT 9968524)

Vygotsky, L. S., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walsh, B. (1997). Education in precarious times: Postmodernity and a Christian worldview.

Sydney: Centre for the Study of Australian Christianity.

White, E. G. (1903). Education. Mountian View, CA: Pacific Press.

White, E. G. (1911). The acts of the apostles. Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press.

Wolterstorff, N. (1997). The crumbling walls of certainty: Towards a Christian critique of postmodernity & education. Sydney: Centre for the Study of Australian Christianity.

Yorks, L., & Marsick, V. J. (2000). Organizational learning and transformation. In J. Mezirow & Associates (Eds.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (pp. 253-281). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

The authors are members of the faculty of the graduate Leadership Program at Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan. Shirley A. Freed, Ph.D., is Professor of Leadership and Qualitative Research, Duane M. Covrig, Ph.D., is Professor of Leadership and Educational Administration, and Erich W. Baumgartner, Ph.D., is Professor of Leadership and Intercultural Communication.