Abstract: Even though the leadership literature has studied the antecedents and outcomes of virtuous leadership, there is a scarcity of research on the influence of virtuous leadership on organizational performance in Christian organizations. Therefore, this study developed a theory of virtuous leadership and its influence on organizational performance grounded in the perceptions of leaders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Using classic grounded theory methodology, data was collected by interviewing eight leaders of the Adventist Church from the MENA region. The emergent theory of virtuous leadership revolves around the key role of spirituality (source) in enhancing the leader’s love (motive), character (spirit), and leadership style (method). As this kind of virtuous leadership increases, there will be a positive effect on the organization’s performance as leaders foster vision, a positive work environment, people, and growth. The article concludes with practical implications for Christian leaders and recommendations for those serving in the MENA region.

Keywords: virtuous leadership; organizational performance; spirituality; Seventh-day Adventist Church; MENA; grounded theory

Introduction

Leadership is a complex notion and process (Maxwell, 2008; Nicolae, Ion, & Nicolae, 2013). Despite the attempts of many researchers, the concept of leadership is still ever-evolving, and our understanding of it is often stretched. Bennis (1959) made an interesting observation long ago that, to a certain degree, still applies today:

Always, it seems, the concept of leadership eludes us or turns up in another form to taunt us again with its slipperiness and complexity. So we have invented an endless proliferation of terms to deal with it . . . and still the concept is not sufficiently defined. (p. 259)

Leadership has been examined and defined in numerous ways. It is well noted that there is a deep-rooted history of leadership being defined by virtue and character in both the Eastern and Western cultural settings (Bauman, 2018; Ghosh, 2016; Wang & Hackett, 2016). Prominent ancient scholars such as Confucius in the East and Aristotle in the West related and contributed to the definition of leadership in terms of virtue and character (Koehn, 2016; Wang & Hackett, 2016).

Interest in leadership based on virtue has increased in recent years.

Numerous studies and much literature have explored the antecedents, distinctions, and even the outcomes of virtuous leadership (Crossan, Mazutis, & Seijts, 2013; Flynn, 2008; Palanski & Yammarino 2007; Wang & Hackett, 2016). Nevertheless, there remains a gap concerning the influence of virtuous leadership on organizational performance in Christian organizations. This article attempts to reduce this gap by exploring the impact of virtuous leadership on organizational performance from the perceptions of Seventh-day Adventist leaders in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

This article is organized with a description of the methodology used, the presentation of the emergent spirituality theory of virtuous leadership and its influence on performance, the similarities and differences between our theory and existing conceptualizations in the literature, and finally, conclusions and recommendations.

Methodology

This section will discuss the methodology employed for this article, including a discussion of data collection, the method of analysis used, and a brief overview of study participants. Since the study’s objective was to develop a theory of virtuous leadership and its influence on organizational performance grounded in the perceptions of leaders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in MENA, the chosen research design was classic grounded theory (CGT). CGT is a methodology used to build theory from data and discover the participants’ main concerns (Glaser, 1998). Three different data sources were used, including interviews with eight leaders, existing literature, and theoretical memos.

Data Collection and Analysis

We used CGT’s dictums to ignore preconceived ideas, make a constant comparison, and employ theoretical sampling (Biaggi & Wa-Mbaleka, 2018; Glaser, 1992, 2013; Suddaby, 2006; Urquhart, 2013). First, to ignore preconceived ideas, the researcher who conducted data coding and analysis did not read any literature until the literature was incorporated as data. Second, constant comparison was implemented through three types of comparisons (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Holton, 2007; Evans, 2013): incidents with incidents (resulting in codes), codes with more incidents (resulting in categories), and categories with categories (resulting in propositions). Third, theoretical sampling was performed by letting the emergent theory determine “the what (data), who and how many (participants), where, how, and when to collect data” (Biaggi & Wa-Mbaleka, 2018, p. 7).

Coding was done using Glaser’s open, selective, and theoretical coding (Glaser, 1978). First, we assigned codes to each incident (open coding). Then, categories (or themes) emerged as we arranged and rearranged codes into groups (selective coding). Finally, the theory emerged by connecting the categories (theoretical coding).

We followed Glaser’s procedures, which are divided into inputs and outputs (Glaser, 1978; 1998). The inputs include collecting, coding, and analyzing the data. Thus, we started by interviewing one participant, then coding and analyzing the field notes taken during the interview. Following theoretical sampling (as explained above), we interviewed new participants until reaching theoretical saturation—seeing “similar instances over and over again . . . [becoming] empirically confident that a category is saturated” (Glaser & Strauss, 1967, p. 61). Though we recorded the interviews, we did not write transcripts (Glaser, 1998) but instead listened to the recording when unsure about an incident.

The outputs included categorizing, memoing, sorting, and writing the theory. While categorizing was done in the selective coding (as explained above), memoing was done by writing theoretical memos—records of our insights and ideas which were useful for raising the level of analysis from description to theorization (Glaser, 1978). Codes, categories, and theoretical memos were sorted multiple times, yielding results that were especially relevant for discovering the core category and theoretical coding. Finally, we wrote the theory, and as suggested by Glaser (1978, 1998), we first incorporated the literature.

The reader must understand that this theory is fully based on the data used, and that our report focuses on the theory rather than on illustrating or exemplifying each concept and category.

The credibility of the theory should be won by its integration, relevance and workability, not by an illustration used as if it were proof. The assumption of the reader, he should be advised, is that all concepts are grounded, and that this massive grounding effort could not be shown in writing. Also, that as grounded they are not proven; they are only suggested. The theory is an integrated set of hypotheses, not of findings. Proofs are not the point. (Glaser, 1978, p. 134)

To help the reader understand the grounding process used, we will show one piece of data from the Field Notes (FN) and explain the coding and analysis procedure. For example,

God doesn’t promise a work free from danger. I was kidnapped twice, but I was not afraid. I had full assurance that God would find a way to get me out of this problem. It didn’t matter if the problems were big or small. (FN, p. 2)

In the initial open coding phase, this incident was coded as not afraid. Then, during the selective coding phase, as we arranged codes into themes. We initially categorized not afraid under a faith theme, which was grouped under a courageous category. Later, as the grounded concepts started emerging, we rearranged and resorted the codes to keep the dimensions and properties contributing to the emerging theory (Elliott & Higgins, 2012). Thus, not afraid was included as a component of courage, which was categorized as a sub-property of dedicated, helping to describe the passion dimension of the character (spirit) of the virtuous leader.

Participants

Eight leaders were interviewed, selected based on theoretical sampling (as explained above), and based on their experience as leaders of a Seventh-day Adventist organization in the MENA region; they were selected to represent as many countries as possible of the MENA region. Though born in eight different countries of MENA, some of the leaders hold multiple citizenships. All participants were male, and their average age was 55.1 years. They had 28.8 years of experience on average; of these, they worked an average of 22.1 years within MENA, and 7.6 outside MENA. Participants accepted and signed an informed consent form, agreeing that their participation was voluntary and confidential. Table 1 shows participants’ citizenship, the countries in which they had served, and the roles in which they had served.

Table 1

Participants’ Demographics

A Spirituality Theory of Virtuous Leadership

| Citizenship | Countries served | Roles/Profession |

| MENA: Algerian, Egyptian, Jordanian, Iranian, Iraqi, Lebanese, Sudanese, Tunisian | MENA: Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, UAE, Yemen | Accountant, administrator, NGO director, pastor, secretary-treasurer, president, teacher |

| Other: American, Armenian, Cypriot, New Zealand, Swiss | Other: Cyprus, Fiji, France, Liberia, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Rwanda, USA |

Now we will explore and present the emergent spirituality theory of virtuous leadership, developed based on the perception of the interviewees in this study, as the purpose was to develop a theory of virtuous leadership grounded in the perceptions of Adventist leaders in the MENA region. Four categories emerged: spirituality, love, character, and leadership style. Of these, spirituality emerged as the core category that “explains how that concern [virtuous leadership] or problem is managed, processed, or resolved” (Holton & Walsh, 2017, p. 88). When a leader is spiritually strong, his motivation to lead by love will be purified, his spirit and/or character will be dignified, and his method or leadership style will be refined. In this section, we will unpack this emergent theory of virtuous leadership.

Spirituality

A virtuous leader is a spiritual leader who puts God first and who relies on God. “Remain in me, as I also remain in you. No branch can bear fruit by itself; it must remain in the vine. Neither can you bear fruit unless you remain in me” (John 15:4, NIV). A leader puts God first by having a relationship with Him; that relationship starts early each day with a personal morning devotion time, including prayer and Bible study. The leader who puts God first is viewed as a man or woman of God who is Christ-centered and who shapes his or her life using the Bible as a blueprint. One participant mentioned that knowing God personally is a prerequisite to being a virtuous Christian leader and will result in “all virtues coming automatically” (FN, p. 2). Thus, God should be the leader of the leader (TM,1 p. 56), helping the leader in all small details.

In addition, the spirituality of a virtuous leader can be demonstrated in how s/he relies on God for all decision-making. Relying on God involves being committed to the Lord in every circumstance, being God’s partner, and depending on God. For example, one participant mentioned he knew a virtuous leader who made God his partner in how he led his family business (a chocolate biscuit company); one example of such partnership was the return of a yearly tithe of the company’s profit (FN, p. 2). Where a person is in his or her relationship with God has a major impact on leadership. Table 2 summarizes the dimensions, properties, and sub-properties of spirituality.

Table 2

Spirituality’s Dimensions and Properties

| Category | Dimensions | Properties | Sub-properties |

| Spirituality | God first | Relationship with God Man of God | Prayer, personal morning devotion Christ-centered, Bible as blueprint |

| Relies on God | Committed to the Lord Partner of God | Depends on God |

Love (Motive)

Love is the motivation for virtuous leadership. Love is vital for service (leadership style) because love is a prerequisite for service (TM, p. 122). “If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing” (1 Cor. 13:3, NIV). Love is more important than honesty and integrity (character) because, without love, even a person of character (i.e., trustworthiness, work ethic, and passion) becomes hard to follow.

Love’s dimensions are kindness, patience, empathy, redemption, and selflessness. Kindness refers to goodness and dealing with people’s feelings with emotional intelligence. Patience is shown, for example, when the leader takes time to mentor a subordinate. A loving leader also shows empathy and sympathy; that is, s/he is friendly and approachable, with no “friendship agenda” or ulterior motives. He is also redeeming, seeking to build others up, desiring to help followers grow. The leader gives more chances after failure, using mistakes as learning opportunities for subordinates. A loving leader is selfless, sacrificing time and resources; s/he is benevolent. Table 2 presents the dimensions, properties, and sub-properties of love.

Table 3

Love’s Dimensions and Properties

| Category | Dimensions | Properties | Sub-properties |

| Character (spirit) | Kindness | Goodness | Kindness for people’s feelings |

| Patience | Takes time to mentor | ||

| Empathy | Sympathy | Friendly, empathy for subordinates’ feelings | |

| Redemption | Builds others up | Desires to help | |

| Selflessness | Sacrifices time and resources | Benevolent |

Character (Spirit)

According to the participants, the spirit of a virtuous leader is his or her character, and this character has five dimensions: trustworthiness, work ethic, contentment, passion, and respect. One of the wisest persons who ever lived, King Solomon, declares that a trustworthy person brings healing (Prov. 13:17, NIV). First, a leader is trustworthy when he is reliable, truthful, genuine, accountable, and faithful. He is reliable because he listens, counsels and prays, but keeps sensitive information confidential—no blackmail, no betrayal. A virtuous leader is truthful when she walks the talk, when she practices what she preaches, and when she is honest and credible. A leader is genuine when followers perceive that s/he is authentic, real, and sincere—a person of integrity. A virtuous leader is accountable when he has nothing to hide, is transparent in all areas of life, and is straightforward. A leader is faithful when serving as a “sheep dog,” protecting his or her followers by being behind and beside them (FN, p. 4).

The second dimension of the character of the virtuous leader is work ethic. Work ethic is a vital aspect of what constitutes a leader’s character. After all, as Paul emphatically referenced in the epistle to the Colossians, “Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for human masters” (Col. 3:23, NIV). The leader’s work ethic can be described with five properties: persevering, risk-taking, being just, hard-working, and disciplined. She perseveres despite challenges; she is consistent. A virtuous leader is a risk-taker— especially to help others—and takes advantage of available opportunities. She is just, fair to employees, and plays no politics or games. She shows no favoritism, giving equal treatment among equals. She does not overload workers or exploit them. A virtuous leader is hard-working, industrious, and diligent. Her work ethic is disciplined, methodical, and efficient.

The third character trait of a virtuous leader is contentment. The underlying meaning of contentment, as implied by Paul, is a total reliance on God to supply one’s needs (Phil. 4:10–13). Contentment involves satisfaction, humility, and selfcontrol. The virtuous leader is satisfied, puts expectations aside, and commits to a higher purpose. This can frequently be seen when the leader is satisfied even with little salary, not coveting or looking around for other jobs. Contentment is also reflected in the leader’s humility; he may have knowledge and burdens but passes his time with his people. He is not proud but humbly serves. He also has the self-control to take hold of his personal interests, emotions, and agenda. Referring to self-control, one participant said, “The worst enemy is your inner self” (FN, p. 5).

Another character trait of a virtuous leader is passion. Passion refers to dedication, zeal, devotion, decisiveness, courage, and hope. The leader is courageous to go through trials, whether small or big. One participant shared his story of courage as he was kidnapped twice. He said, “I was not afraid. I had full assurance that God was going to find a way to get me out of that problem. God did not promise a work free from danger” (FN, p. 2).

Finally, a virtuous leader’s character includes respect. This trait has two sides: the leader is respectful, and he is respected. For example, he is respectful of others’ faiths and beliefs, and as a result, he gains respect and confidence. Talking about sharing one’s faith, a participant mentioned that respect is shown when a leader sits down with someone of a different religion to listen (FN, p. 1). He further illustrated this by pointing out that a respectful leader avoids the polemic method (i.e., trying to convince people of what is right by showing them what is wrong) and instead uses the jigsaw method (i.e., subtle, piece by piece) (FN, p. 2). Table 4 presents the dimensions, properties, and sub-properties of character.

Table 4

Character’s Dimensions and Properties

| Category | Dimensions | Properties | Sub-properties |

| Character (spirit) | Trustworthiness | Reliable Truthful Genuine | Confidential Honest, credible Authentic, integrity, no double face, real, sincere |

| Accountable | Transparent, nothing to hide, straight-forward | ||

| Faithful | Emphasizes values | ||

| Work ethic | Perseverant Risk-taker Just | Consistent Takes opportunities Fair, no politics/games, no favoritism, doesn’t overload workers, no exploitation | |

| Hard-working | |||

| Disciplined | Methodical | ||

| Contentment | Satisfied Humble Self-control | Expectations aside | |

| Passion | Dedicated | Zealous, devoted, decisive, courageous (not afraid), positive (hopeful) | |

| Respect | Respectful | Respected, people’s skills |

Leadership Style (Method)

A virtuous leader’s method of work—or leadership style—includes servant leadership, wisdom, competence, commitment, and mentorship.

Servant leadership involves an iterative process of thinking about others, mingling with them, listening, building rapport, and caring for people (Mark 9:35, NIV). These phases do not follow a rigid order but rather can be seen in the life of a servant leader. First, the leader thinks about others; the heart of love of the leader fills his mind with goodwill. Thinking about others includes thoughts about how he or she can look after and help his or her followers. Then, the leader mingles with people, visits them in their homes, calls them, and keeps in touch. While mingling, the leader listens, allowing her to understand people’s feelings and get to know them. Listening builds rapport with people and make people relaxed with mutual spontaneity. Finally, when rapport is built, the leader takes care of people’s needs, giving support where it is needed. The leader genuinely cares for his followers, building relationships, and a strong commitment.

The second dimension of a virtuous leader is wisdom. Wisdom involves prudence, the ability to be cautious and thoughtful, to make wise decisions. Wisdom originates from the fear of God, as Solomon suggests (Prov. 9:10). Wisdom also can be seen by how the leader surrounds herself with talent; beginning from the selection process, she identifies, attracts, and surrounds herself with the talent she sees in every person. Her wisdom does not make her proud but helps her to remain a humble lifelong learner, submissive, and merciful (Jas. 3:17). Wisdom also provides the virtuous leader with the ability to be a clear communicator without the fear of losing her position.

Competence also characterizes a virtuous leadership style. Competence involves good administrative skills, intelligence, creativity, problem-solving, and knowledge. One participant shared that a virtuous leader showed creativity by “seizing the opportunity:” he invited guests at his home to join him for Bible lessons and prayed with them.

Another dimension of leadership style is commitment. The virtuous leader is committed to do God’s work, voicing His values, and being courageous. When facing a problem, he does not quit but speaks up. He is courageous to face trials, make tough reforms, break hostile environments, and be criticized or misunderstood.

Another key dimension of the virtuous leader’s leadership style is mentorship, which is displayed by empowering followers, developing them, and being a true leader rather than a boss. Empowering involves delegation and giving freedom and voice. The virtuous leader challenges followers, gives them tasks, allows them to make decisions, includes them, and works closely with them as needed. As she delegates, she allows followers to make and execute their own plans and decisions but keeps them accountable. She gives freedom and voice to choose creative ways to achieve objectives. As one participant mentioned, empowering is “achieving greatness by drawing greatness in people” (FN, p. 4). Mentorship also includes developing followers, which involves identifying talent, using mistakes to mentor and build up, building on positives, and developing by experience. One participant mentioned that when he made a mistake, his leader used it to teach him how to deal with that issue; thus, he grew and was mentored, learning how to deal with mistakes from others, and avoiding the same mistake in the future (FN, p. 3). Virtuous leaders also build on positives; they identify the positives and help people believe in themselves, challenging them to do the best they can.

Finally, the virtuous leader is a true leader—not a boss. He mentors by example, challenges others, and is a supportive team player. When the disciples asked Jesus in Samaria whether He would agree to ask God to send fire from heaven to kill the Samaritans (Luke 9:51–56), Jesus mentored them with His example. The character of the disciples was radically changed as a result. Table 5 presents the dimensions, properties, and sub-properties of leadership style.

Table 5

Leadership Style’s Dimensions and Properties

| Category | Dimensions | Properties | Sub-properties |

| Leadership style (method) | Servant (practical ministry) | Thinks about others Mingle | Looks after, offers help Calls, visits homes, keeps in touch |

| Listens Builds rapport | Understands, knows people Makes people relaxed, spontaneous | ||

| Takes care | Gives support | ||

| Wisdom | Prudent Surrounds himself with talent Learner Clear communicator | Subtle (jigsaw puzzle method), cautious, thoughtful | |

| Competence | Ability Intelligent Creative Problem solver | Good administrative skills | |

| Knowledgeable | Knows and understands Christian beliefs and those of other religions | ||

| Commitment | To God’s work To voice his values To be courageous | To face trials, to clean up, to break hostile environments, to be criticized or misunderstood | |

| Mentorship | Empowerment | Delegates, gives freedom, gives voice | |

| Develops others | Identifies talent, uses mistakes to mentor/build-up, builds on positives, by experience | ||

| Leader-not boss | Mentors by example, challenges others, supportive, team worker |

This grounded theory of virtuous leadership can be summarized by two propositions:

Proposition 1: Virtuous leadership can be explained by the leader’s level of spirituality (source), love (motive), character (spirit), and leadership style (method).

Proposition 2: When a leader is spiritually strong, his motivation to lead by love will be purified, his spirit or character will be dignified, and his method or leadership style will be refined.

Influence on Performance

In this section, we will succinctly discuss the impact of the theory on the overall performance of the organization and those involved. When a leader with the above-mentioned virtues is at the helm of an organization, performance improves. Our emergent theory proposes four areas of improved performance: a clear vision, a transparent work environment, trusting people, and organizational growth. These four areas are part of this study and emerged from our analysis of the answers the participants provided during the interviews. Next, we will explain these four categories of improved performance.

Vision

Vision is intrinsically a vital part of leadership. It gives purpose and clarity to the trajectory in which the organization is heading. In the words of one participant, a vision is the “where to go, [the] purpose” (FN, p. 5). A clear vision enables a virtuous leader to positively impact the given organization and/or the people s/he leads.

As discussed in the previous sections, a virtuous leader, sets a vision that engages, compels, and encourages the involvement of followers and constituents (i.e., churches) in projects that would potentially generate or be translated into positive results. The vision is not exclusively and solely limited to the leader, but it is therefore bestowed upon the followers. As a virtuous leader sets the vision, s/he further helps the followers to own the vision and equips them with the necessary resources to carry out tasks (FN, p. 7).

Work Environment

The work environment is simply the context within which the virtuous leader operates and leads. The virtuous leader can fulfill the responsibility to create a work environment with an organizational culture founded on accountability, service, and responsiveness to social expectations. A participant emphasized the importance of culture as nuanced in this statement — “people leave, people die, but culture stays” (FN, p. 6). The same participant suggested that three stages—policy, standards, and culture (not in order of importance)—must be upheld to enable a virtuous leader to create such a work environment. To further explain the stages, the participant referred to the following illustrations (FN, p. 6):

- Policy: Don’t smoke. Don’t come with slippers and shorts.

- Standard: Dress properly.

- Culture: In our culture, we don’t smoke; we are kind, don’t wear this, we respect, we love, eat together, trust [sic].

As with creating a solid culture, the virtuous leader can also engrave transparency into the identity of the work environment. The leader is cautious when relating to the organization’s resources, not squandering the resources entrusted to him or her, and is clear in reporting to those to whom s/he is accountable. One participant highlighted that an example of not squandering resources and a clear indication of wise usage of finances is the abstinence from purchasing business class tickets (FN, p. 7).

A virtuous leader can rise above personal interest and her own agenda and emotion when dealing with/managing a crisis. A virtuous leader ensures that the work environment exhibits a quality of a high sense of justice, in which errors are corrected. When justice is served in the workplace, the work environment echoes the statement of one participant, “God won’t save policies, but people” (FN, p. 5). This is in line with the rationale that while applying the law is important, understanding the spirit of the law is critical. The virtuous leader ensures that the work environment promotes this view.

In a nutshell, the organization’s members’ perceptions of the work environment are tuned and set in motion by the virtuous leader, which significantly affects the organization’s overall performance.

People

As the virtuous leader sets the vision, helps followers buy-in, and creates the work environment that influences the organizational performance, the people (community, subordinates, and beneficiaries) affiliated with the organization reap the benefits. A virtuous leader seeks the betterment of and invests in the people. S/he empowers, disciples, educates, delegates, mentors, communicates, coaches, includes, and, above all, seeks the spiritual growth of the people affiliated with the organization. Investing in and trusting people are requirements that a virtuous leader should take to heart.

A virtuous leader positively influences subordinates, making efforts to promote trust, teamwork, well-being, and belonging. Trust increases as the levels of self-confidence, credibility, security and freedom increase. Higher levels of teamwork enable promotions and mentorship to take place. Furthermore, followers of a virtuous leader enjoy higher levels of well-being as they are cared for and have a balanced life. They also feel a sense of belonging to the organization as they fellowship with each other. As a result, there is growth in organizational performance, followers experience higher job satisfaction, and there is lower turnover and higher organizational commitment.

As the people perceive the efforts the leader makes to know them, they reciprocate by trying to know the leader. As a result, they follow the leader (FN, p. 5). Followers will also give all of themselves (even go the extra mile) to avoid disappointing the leader, reach the goals, or help the organization. They will feel more committed to the leader and the organization; this, in turn, will create greater job satisfaction. All this is the fruit of feeling valued (invested in) and feeling that one is doing something that matters. Such followers will advocate for the organization, and they will help others to meet the standards to reach the goals (TM, 9).

Beneficiaries and stakeholders also benefit from a virtuous leader. For example, in a church setting, the members (beneficiaries) are better discipled, motivated, and spiritually enriched. The beneficiaries are discipled because the leader makes efforts to train them and be close to them (intimacy) in a context of good interpersonal relationships. They are motivated because they feel confident in their growth, and they are spiritually enriched through the many camp meetings and seminars the leader organizes. A virtuous leader is also well respected by stakeholders—such as the surrounding community—for his hard work on their behalf, being sincere, and establishing long-term relationships.

Growth

Having a clear vision, establishing a transparent work environment, and trusting people may cause organizational growth. A virtuous leader sets the stage for such growth, which often occurs in finances and operational expansion. One participant suggested that prudence in financial stewardship is important. When members are aware that leadership is not squandering resources, they are encouraged to take increased roles in supporting the organization. Donors are also encouraged to donate; one participant gave an example of how tithe soared in a matter of a few years to an 80% increase (FN, p. 7). The growth in tithe return and donations enabled the organization to become self-supporting.

A virtuous leader also drives the expansion of the organization. Increased numbers of baptisms or growth could indicate expansion in the operations of the organization. One participant referred to how the operation of one NGO increased from one office with four employees to four offices with about 70 employees. The expansion enabled the NGO to cover a larger territory, which, in turn, enabled it to aid to more people in need (FN, p. 6). Expansion may also result from improved productivity.

This section can be summarized with a third proposition.

Proposition 3: A virtuous leader positively influences the organization’s performance by providing a clear vision, transparent work environment, and people who trust—all of which result in organizational growth.

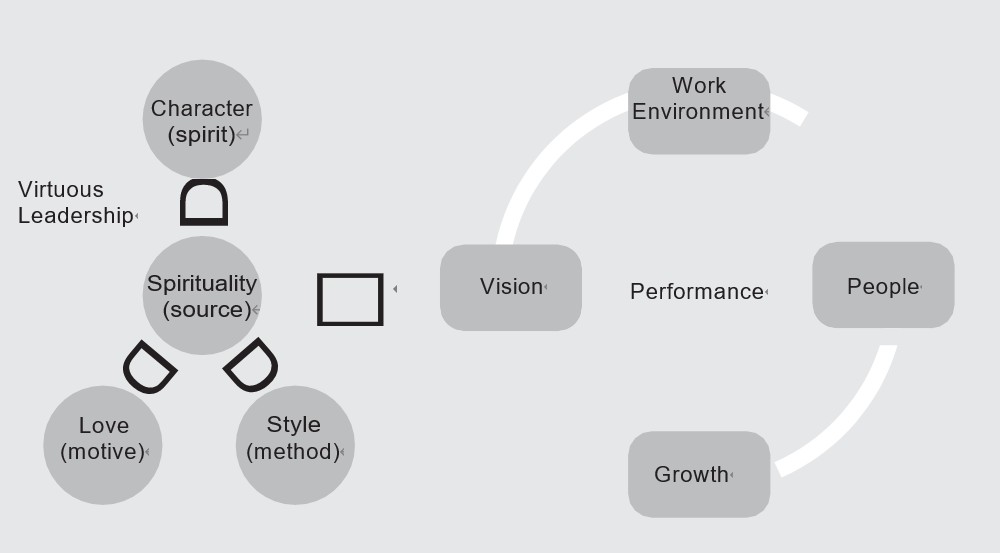

The three propositions of this theory are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The Spirituality Theory of Virtuous Leadership and Its Influence on Organizational Performance

The Spirituality Theory of Virtuous Leadership and the Literature

In this section, we will briefly analyze the theoretical contribution of this spirituality theory of virtuous leadership. In this analysis, we highlight similarities and differences between our theory and existing conceptualizations in literature. Our analysis includes literature on virtuous leadership (from both secular and Christian perspectives) and literature on other leadership theories related to our main categories (specifically spiritual leadership and love leadership).

Similarities

Spirituality

Many authors include spirituality, relationship with God, faith, daily devotion, and prayer as important elements for a good or virtuous leader (Blackaby & Blackaby, 2001; Doohan, 2007; Goldberg, 2017; Manuel, 2017; Nicolae, Ion, & Nicolae, 2013; Sanders, 2017; Thompson, 2017; White, 1925). For example, Goldberg (2017) argues that “spirituality does indeed influence everything a leader does and is, whether thinking or behavior attributes, and the process of a leader’s questioning” (p. 105).

Love

Though sometimes with different words, all dimensions and properties of love are found in the literature. For example, kindness is referred to as compassion (Koko, 2017; Traxler & Covrig, 2012) or tact (White, 1925). Sympathy is referenced as respect (Bryant, 2009), redemption as supportive (Stallard, 2015), and selflessness as giving (Bryant, 2009) or caring (Stallard, 2015).

Character

Almost all dimensions and properties included in our conceptualization of character are supported by existing literature. Sometimes with the same terms and sometimes with synonyms, trustworthiness (Dawson, 2018), work ethic (Doohan, 2007), contentment (Manuel, 2017), passion (Ghosh, 2016), and respect (Dawson, 2018) are mentioned in the literature.

Leadership Style

Most dimensions and properties of leadership style are supported in the literature. For example, the main dimension of leadership style—servant leadership—has become a leadership theory on its own (Blanchard & Broadwell, 2018; Blanchard & Hodges, 2003; Greenleaf & Spears, 2002; Hunter, 1998). Additionally, wisdom and prudence are considered important virtues in literature (Boshart, 2007; Wang & Hackett, 2016).

Performance

The four dimensions of performance support existing literature. Vision and purpose (Doohan, 2007; Newstead, Dawkins, Macklin, & Martin, 2019), the context of a work environment of transparency (Tonstad, 2017) and of an organizational culture of accountability (Tonstad, 2017), people that trust (Newstead et al., 2019), belong (Stallard, 2015), and are motivated (Newstead et al., 2019), and growth through performance and task excellence (Stallard, 2015) are benefits of virtuous leadership found in the literature.

Differences

Spirituality

Some authors (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) refer to transcendence as a proxy for spirituality, including the spiritual aspects of religions beyond Christianity (e.g., Buddhism, Hinduism, etc.). However, in this study, spirituality refers exclusively to the leader’s relationship with and dependence upon the God of the Bible. Though conceptualizations of spiritual leadership exist (Blackaby & Blackaby, 2001; Fry, 2003; Goldberg, 2017; Koko, 2017; Sanders, 2017), one key theoretical contribution developed in this article is placing spirituality at the core of virtuous leadership. In a nutshell, spirituality is the key for virtuous leadership, and its level directly influences the quality of all other aspects of virtuous leadership (love, character, and leadership style).

Love

Though some authors argue that vulnerability is key for love (Bryant, 2009; Cochlan, 2012), our participants did not mention it as a key dimension of love as motive for virtues. Although, for some authors, love is the crucial element of leadership (Bryant, 2009; Cochlan, 2007; Stallard, 2015), in our theory, love—the heart’s motivation for virtue—depends on the level of spirituality.

Character

One key difference of this theory is downplaying the importance of courage as a virtue. While courage is considered to be one of the main virtues when short lists of virtues are offered (Bauman, 2018; Ghosh, 2016), in our theory, courage is described as the absence of fear and is considered to be a property of passion. Though some leadership theories point to temperance as a key virtue (Ghosh, 2016; Wang & Hackett, 2016), temperance did not emerge in our theory. However, trustworthiness emerged as a key character trait of a virtuous leader.

Leadership Style

While some researchers have considered entrepreneurship a virtue (Dawson, 2018), it did not emerge in our theory. However, creativity and problem solving emerged as properties of competence while apparently neglected in the literature. Similarly, surrounding oneself with talent emerged as a property of wisdom that the literature seems to have ignored.

Performance

One element that our theory adds to the influence of virtuous leadership on performance is that often, virtuous leaders can develop an organizational structure (as part of the work environment) conducive to flourishing. Another aspect of the work environment that this theory adds to the literature is that virtuous leaders are good at managing crises (also, as part of the work environment). Though the literature points to performance and task excellence (Stallard, 2015), our theory adds to existing literature financial growth as a benefit of virtuous leadership.

Implications for Practice

This section will cover the overall implications of this theory for leadership practice. It will also include recommendations for leaders of Christian organizations and more focused recommendations for leaders specifically serving in the MENA region.

Recommendations for Leaders of Christian Organizations

This theory is relevant for administrators and leaders of Christian organizations who desire to achieve improved organizational performance through enhanced virtuous leadership. Based on our theory’s categories, dimensions, and properties, we recommend leaders seek ways to strengthen their virtues and nurture virtues in subordinates by utilizing the following suggestions.

Put God First

A daily relationship with God will enable you, as a leader, to cast a clear vision based on heavenly truth and duty. Because “spirituality does indeed influence everything a leader does and is, whether thinking or behavior attributes, and the process of a leader’s questioning” (Goldberg, 2017, p. 105), putting God first daily is critical. We suggest leaders spend the first hour of each day in prayer, studying God’s word, and meditating. Thus, leaders “will be connected with heaven and will have a saving, transforming influence upon those around them. Great thoughts, noble aspirations, clear perceptions of the truth and duty to God, will be theirs” (White, 1948, p. 112).

Be a Servant Leader

A virtuous leader is a servant leader. Thinking about others, offering help, visiting people in their homes, listening, building rapport, and giving support as needed are some practical actions warranted. Leaders of churches should remember that

Christ’s method alone will give true success in reaching the people. The Saviour mingled with men as one who desired their good. He showed His sympathy for them, ministered to their needs, and won their confidence. Then He bade them, “Follow Me.” (White, 1905, p. 143)

When leaders follow Christ’s example of servant leadership, they reap great results and relationships (Blanchard & Broadwell, 2018), finding legitimate greatness and power (Greenleaf & Spears, 2002).

Transfer Character

Exercise your leadership in such a way that Bible-based principles of your character will impact the life of your team. The goal is that others will want to have such type of character virtues. Paul said, “Follow my example, as I follow the example of Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1; NIV). For this to happen, leaders must be transformed themselves by putting God first. Then, they will be able to mentor by example (Sosler, 2017) when recognizing teachable moments (Newstead et al., 2019).

Communicate Clearly

Communicate with decisiveness and gentleness, allowing for open dialogue with your teammates so that subordinates freely accept your vision and plans as their own, securing its implementation. Plans achieve a higher implementation rate and success when they are owned by everyone involved; appropriate communication plays a key role (Dawson, 2018; Washington, 2017).

Be a Humble Learner

As a virtuous leader you will humbly recognize that God calls on you to continuously improve. You can achieve a love for learning (Manuel, 2017), which will yield increased psychological safety (Newstead et al., 2019). We agree with White (2017b) that

men [and women] in responsible positions should improve continually. They must not anchor upon an old experience……Man, although the most helpless of God’s creatures when he comes into the world…… is nevertheless capable of constant advancement. He may be enlightened by science, ennobled by virtue, and may progress in mental and moral dignity, until he reaches a perfection of intelligence and a purity of character but little lower than the perfection and purity of angels. (p. 93)

What a goal for each leader!

Be Transparent and Accountable

Your trustworthiness depends on your transparency and accountability. Have nothing to hide; be straightforward. Exercise integrity in all you think, say, and do. “Everything is to be done with the strictest integrity. Better consent to lose something financially than to gain a few shillings by sharp practice . . . everything done without fraud, without duplicity, without one tinge of guile” (White, 2017, p. 1158). If you want to be a virtuous leader, be transparent, responsible (Cameron, 2011), and accountable (Thompson, 2017).

Infuse Harmonious Cooperation, Unity, and Teamwork

Foster among your team members mutual cooperation and unity, which are essential to a harmonious whole. We encourage you to develop a teamwork atmosphere in your organization (Fillingham, n.d.), challenging colleagues and subordinates to cooperate and support each other (Dawson, 2018). Be a leader that mentors by example (Sosler, 2017). If you are a church leader, do not think that your skills and gifts are enough to carry the work; instead, allow God to show you how different individuals can contribute to the work in unity and cooperation (White, 2014).

Love Your Subordinates

As a person striving to be a virtuous leader, you must love your subordinates. But what is the source of love? God is love (1 John 4:16), and all good things come from God (James 1:17). Therefore, love has its original source in God (spirituality). Some leaders recognize the source of love and work towards enhancing their relationship with God (intentional source). Others do not recognize God’s existence but show loving leadership (TM, p. 125). They receive love and develop it, unaware of its source (unintentional source) (TM, p. 126). If the leader rejects God’s existence, the level of love has limits. Since love is the essence of God when a person purposefully denies God’s existence and rejects knowing Him, he can only get a limited knowledge of God (in nature, people, etc.), and therefore understanding a limited portion of love (TM, p. 127).

How can a leader increase her level of love? She should go to love’s source (Koko, 2017), make decisions based on God’s revelation (Bible), ask God for it, relate with loving people, and practice loving acts (TM, p. 128). In an organization, a virtuous leader shows love by knowing the subordinates (you can’t love someone you don’t know), knowing the beneficiaries, sharing life with them (time, food, talk), being vulnerable, being intentional in showing compassion (Traxler & Covrig, 2012), and giving opportunities for others to show love to her in return. When the leader’s love is authentic (Cochlan, 2012), followers give all of themselves (even becoming willing to go the extra mile) to avoid disappointing the leader, reach the goals, and help the organization. They will feel more committed to the leader and the organization. They will have greater job satisfaction. All this is the fruit of feelings of being valued, of doing something that matters. They will advocate for the organization. They will help others to meet the standards to reach the goals (TM, p. 130).

A loving leader may not automatically have wisdom (ability, strategy, vision, knowledge of how to discipline, or of how to motivate). However, God can give both love and wisdom (TM, p. 131). Secular leaders can grow in wisdom, but their wisdom also has a limit because human wisdom cannot be compared with the wisdom God can give. A leader with both love and wisdom has a daily meeting with employees to share the successes and challenges of the organization (TM, p. 133). He makes followers feel part of it and feel important. He is humble and does any work needed. He is creative and very communicative. He never speaks in a rush (White, 1925); he speaks with self-confidence and humility. In moments of crisis, he shows an unbreakable faith. He says, “We are helpless but not hopeless” (TM, p. 133). The leader may not be equipped for a management position, but his daily relationship with God equips him. God seeks to encounter every person and allows him or her to accept Him in their lives (Rev. 3:20). If a leader denies the true Source of love, his growth in love would eventually reach its limit. This was King Saul’s experience (1 Sam. 18: 12, 28, 29). On the other hand, Paul’s experience on the road to Damascus is an example of accepting Jesus (Acts 9) and tapping into the divine Source of wisdom and love. This opportunity can be a daily choice and even a continuous decision.

Be Visionary

A virtuous leader is one that not only lives in the moment and/or dwells in the past but ponders and plans the future with imagination or wisdom.

Setting a clear and purposeful vision enables the virtuous leader to rally subordinate’s support to endeavor together to fulfill the organization’s mission (Doohan, 2007; Newstead et al., 2019). After all, the vision is for all and not restricted to the leader(s).

Build a Sanctuary

As a virtuous leader, you ought to build a safe haven of the work environment where employees and stakeholders thrive, where accountability and service are engraved in the DNA of the organizational culture, and where social expectations are highly regarded and fulfilled. The work environment is the context that enables the leader to influence subordinates. A virtuous leader establishes an inclusive work environment and promotes transparency (Tonstad, 2017), genuineness, and justice for all those operating in it (White, 1925). The by-product of such effort is perhaps a positive impact on performance.

Invest in People

Your role as a virtuous leader mandates you to invest in the people (community, subordinates, and beneficiaries) being led. A virtuous leader must empower, disciple, educate, delegate, mentor (Sosler, 2017), and coach. Simply put, investing in people reflects the higher calling to which each Christian leader is called:

Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age. (Matthew 28:19, 20, NIV)

Drive Growth

As a virtuous leader, setting the stage for growth is one of your many duties. You drive growth as you exhibit diligence and prudence in the utilization of the resources at your disposal (Ghosh, 2016; Hackett & Wang, 2012). Moreover, you improve the productivity level of your organization as that will translate in growth, too.

If you are a steward of the resources entrusted to you by your constituency, even more so by God, growth is a given expectation. Growth is expected of you as a virtuous leader. Jesus succinctly captures that expectation in the parable of the ten talents, where the master expected the servants to yield returns on the resources left at their disposal (Matt. 25:14–30).

Recommendations for Leaders Serving in the MENA Region

Since our participants hailed from MENA countries, we asked them to offer suggestions for leaders serving in the MENA region. These recommendations revolve around understanding the culture, fostering growth in people, and leading the work.

Leaders need to better understand MENA culture before diving in, as was repeatedly suggested by study participants. Understanding of shame-honor and collectivist cultural mindsets would aid the leader, increasing his or her chances of forming a successful leadership legacy. Moreover, it is also important for the leader to exhibit genuine interest in people, have no agenda, and establish lasting relationships. Another important practice that helps get a perception of the MENA culture is to constantly give ear to the local/indigenous followers. This is important not only for understanding the culture but also for knowing the people’s real concerns.

Development of and investment in the indigenous population is crucial. Virtuous leaders must empower locals and see that they are more engaged in a leadership capacity by delegating tasks and providing speaking opportunities (in churches, camp meetings, etc.). The virtuous leader should spend time nurturing the youth. S/he is to mentor and coach them. It is also equally important for the leader to encourage the spiritual growth of the locals. Helping locals grow closer to God should be one of the high aims of the virtuous leader. As a virtuous leader, s/he has to be exemplary (that is, “walk the talk”). In dealing with locals, there should be no favoritism; fairness should be a constant theme.

Besides understanding the culture and developing the locals, leading the work is paramount; after all, it is God’s work. This is the message a virtuous leader ought to daily live. The virtuous leader is a steward accountable not only to the people but, above all, to God. Such a leader is expected to set the tone and pace at which the work is to follow. It is the virtuous leader’s responsibility to find the best leadership style. In the West, most decisions are made in consensus (e.g., committees), which yields better decisions most of the time, through diluting responsibilities (safer) and turning the wheels very slowly. In the MENA region, leaders are expected to have a strong personality and be decisive. Therefore, it is recommended to use a situational leadership strategy, “weaving in and out” of leadership styles, switching from decisive (individual) to representative (consensus) decision making (FN, p. 7). Finally, the MENA region needs virtuous leaders who are task-oriented, leading people and organizations to achieve objectives and targets that would help them fulfill their mission efficiently and reach their vision.

Conclusion

We believe that this study is one of the first, if not the first, attempt to develop a theory of virtuous leadership and explore its impact on organizational performance grounded in the perception of the leaders of the Seventhday Adventist Church in MENA. Three propositions were set forth from the analysis of the collected data, which encapsulated the study.

First, virtuous leadership is explained by the level of the leader’s spirituality (source), level of love (motive), character (spirit), and leadership style (method). Concerning spirituality, virtuous leadership entails establishing a concrete relationship with God, total reliance on God, and having a partnership with God.

Moreover, virtuous leadership is grounded in love that is extracted from God. Knowing and accepting the existence of God is vital since He is the source of love. The knowledge of God by a virtuous leader yields love (motive) towards others, which ultimately results in selflessly relating to people.

Second, when a leader is spiritually strong, her motivation to lead by love will be purified, her spirit or character will be dignified, and her method or leadership style will be refined. Due to the spiritual strength of the leader, she puts others first and is mindful of them. The leader shows genuine care, builds relations, and establishes a strong commitment. Furthermore, the virtuous leader’s leadership style is rooted in wisdom and characterized by competence. Commitment to God’s work and the ability to mentor others are vital components of this leadership style.

Finally, a virtuous leader positively influences the organization’s performance by providing a clear vision, a transparent work environment, and people who trust each other. All of these result in organizational growth. Clarity in the vision, which is owned by virtually all in the organization, is necessary for the leader to set the direction of the organization. A virtuous leader is involved in harboring and fostering a transparent work environment which promotes strong culture and a sense of togetherness. The leader is also involved in encouraging trust at all levels in the organization, and she further exhibits a genuine interest in the people she leads. Therefore, as the virtuous leader engages in such activities, the positive influence on performance (individual or corporate) becomes almost inevitable.

1Theoretical Memo (TM)

Simon Lasu is an accountant at Middle East University, in Beirut, Lebanon.

Carlos Ernesto Biaggi is dean of the faculty of business administration at Middle East University, in Beirut, Lebanon.

References

Bauman, D. C. (2018). Plato on virtuous leadership: An ancient model for modern business. Business Ethics Quarterly, 28(3), 251–274.

Bennis, W. G. (1959). Leadership theory and administrative behavior: The problem of authority. Administrative Science Quarterly, 4, 259–260.

Biaggi, C., & Wa-Mbaleka, S. (2018). Grounded theory: A practical overview of the Glaserian school. JPAIR Multidisciplinary Research, 32, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.7719/jpair.v32i1.573

Blackaby, H. T., & Blackaby, R. (2001). Spiritual leadership: Moving people on to God’s agenda. Broadman & Holman.

Blanchard, K., & Broadwell, R. (2018). Servant leadership in action: How you can achieve great relationships and results. Berrett-Koehler.

Blanchard, K., & Hodges, P. (2003). Servant leader. Thomas Nelson.

Boshart, D. (2007). Echoes of the Word: Theological ethics as theoretical practice [Review of the book Echoes of the Word: Theological ethics as theoretical practice, by H. Huebner]. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 2(1), 62–68.

Breedlove, J. D., Jr. (2016). The essential nature of humility for today’s leaders. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 10(1), 34–44.

Bryant, J. H. (2009). Love leadership: The new way to lead in a fear-based world. Jossey-Bass.

Cafferky, M. (2011). Leading in the face of conflicting expectations: Caring for the needs of individuals and of the organization. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 5(2), 38–55.

Cameron, K. (2011). Responsible leadership as virtuous leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 25–35.

Cochlan, G. (2007). Love leadership: What the world needs now. New Voices Press. Crossan, M., Mazutis, D., & Seijts, G. (2013). In search of virtue: The role of virtues, values, and character strengths in ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(4), 567–581.

Dawson, D. (2018). Measuring individuals’ virtues in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 147, 793–805.

Doohan, L. (2007). Spiritual leadership: The quest for integrity. Paulist Press.

Elliott, N., & Higgins, A. (2012). Surviving grounded theory research method in an aca- demic world: Proposal writing and theoretical frameworks. The Grounded Theory Review, 11(2), 1–12.

Evans, G. L. (2013). A novice researcher’s first walk through the maze of grounded the- ory: Rationalization for classical grounded theory. The Grounded Theory Review, 12(1), 37–55.

Fillingham, M. (n.d.). Personal qualities of the Christian leader. Crossfire. https://www.afcu.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/14_christian_leaderPDF.pdf

Flynn, G. (2008). The virtuous manager: A vision for leadership in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(3), 359–372.

Fry, L. W. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 14, 693–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.09.001

Gentile, M. C. (2010). Giving voice to values: How to speak your mind when you know what’s right. Yale University Press.

Ghosh, K. (2016). Virtue in school leadership: Conceptualization and scale develop- ment grounded in Aristotelian and Confucian typology. Journal of Academic Ethics, 14, 243–261.

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Sociology.

Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. forcing. Sociology.

Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Sociology.

Glaser, B. G. (2013). No preconception: The dictum. The Grounded Theory Review, 11(2), 1–6.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine De Gruyter.

Goldberg, D. S. (2017). The intersection of leadership and spirituality: A qualitative study exploring the thinking and behavioral attributes of leaders who identify as spiritual. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 11(2), 104–105.

Greenleaf, R. K., & Spears, L. C. (2002). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Paulist Press.

Hackett, R. D., & Wang, G. (2012). Virtues and leadership: An integrating conceptual framework founded in Aristotelian and Confucian perspectives on virtues. Management Decision, 50(5), 868–899.

Holmes, A. F. (2007). Ethics: Approaching moral decisions (Contours of Christian Philosophy Series, 2nd ed.). IVP Academic.

Holton, J. A. (2007). The coding process and its challenges. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage handbook of grounded theory (pp. 265–289). CA: Sage.

Holton, J. A., & Walsh, I. (2017). Classic grounded theory: Applications with qualitative & quantitative data. Sage.

Hunter, J. C. (1998). The servant: A simple story about the true essence of leadership. Prima.

Hursthouse, R., & Pettigrove, G. (2018). Virtue ethics. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archive. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/ethics-virtue/

Koehn, D. (2016). How would Confucian virtue ethics for business differ from Aristotelian virtue ethics? Journal of Business Ethics, 165, 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04303-8

Koko, A. S. (2017). The role of spirituality in the leadership style of organizational lead- ers [Dissertation Abstract]. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 11(2), 107–107.

Lencioni, P. (2016). The ideal team player: How to recognize and cultivate the three essential virtues. Jossey-Bass.

Manuel, W. E. (2017). Missional virtues in leadership: Assessing the role of character strengths of Christian social entrepreneurs in creating missional organizations [Dissertation, Asbury Theological Seminary].

Maxwell, J. C. (2008). The leadership handbook: 26 critical lessons every leader needs. Nelson Books.

Newstead, T., Dawkins, S., Macklin, R., & Martin, A. (2019). The virtues project: An approach to developing good leaders. Journal of Business Ethics, 167, 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04163-2

Nicolae, M., Ion, I., & Nicolae, E. (2013). The research agenda of spiritual leadership: Where do we stand? Review of International Comparative Management, 14(4), 551– 566.

Palanski, M. E., & Yammarino, F. J. (2009). Integrity and leadership: A multi-level con- ceptual framework. Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 405–420.

Pears, D. (1976). Aristotle’s analysis of courage. Philosophic Exchange, 7(1), 43–52. http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/phil_ex/vol7/issl/3

Pearse, S. (2016). Courage, the most important leadership virtue. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/susan-pearse/courage-the-most-importan_b_10186426.html

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues a handbook and classification. American Psychological Association.

Ruffner, B. & Huizing, R. L. (2018). A trinitarian leadership model: Insights from the apostle Peter. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 10(2), 37–51.

Sanders, J. O. (2017). Spiritual leadership: Principles of excellence for every believer. Moody.

Sosler, A. (2017). Love in the ordinary: Leadership in the Gospel of John. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 11(2), 10–16.

Stallard, M. L. (2015). Connection culture: The competitive advantage of shared identity, empathy, and understanding at work. Association for Talent Development.

Strathmore University. (n.d.). Virtuous Leadership: Transforming, life, culture and business. http://www.strathmore.edu/news/virtuous-leadership-transforming-life-culture-and-business/

Suddaby, R. (2006). From the editors: What grounded theory is not. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 633–642. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22083020

Thompson, M. (2017). The need for spiritual leadership. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 11(2), 78–82.

Tonstad, S. K. (2017). Transparency in leadership: The divine governance challenge from the apocalypse. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 11(2), 64–75.

Traxler, B., & Covrig, D. M. (2012). Moral biography of Andrew Jackson. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 6(1), 74–88.

Tyler, K. L. (2013). Principles of Jesus’ healing ministry. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 7(2), 8–20.

Urquhart, C. (2013). Grounded theory for qualitative research: A practical guide. Sage. Wang, G., & Hackett, R. (2016). Conceptualization and measures of virtuous leadership: Doing well by doing good. Journal of Business Ethics, 137, 321–345.

Washington, K. S. (2017). Spiritual leadership in religious organizations: A grounded theory study. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 11(2), 108–108.

White, E. G. (1905). The ministry of healing. Ellen G. White Estate.

White, E. G. (1909). Testimonies for the church (Vol. 9). Ellen G. White Estate.

White, E. G. (1925). Christian service. Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

White, E. G. (1948). Testimonies for the church (Vol. 5). Pacific Press.

White, E. G. (2010). Christian leadership. Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

White, E. G. (2014). Evangelism. Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

White, E. G. (2017). SDA Bible commentary (Vol. 3). Ellen G. White Estate.

White, E. G. (2017b). Testimonies for the Church (Vol. 4). Ellen G. White Estate.

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in Organization (8th ed.). Pearson Education.