It was a hot, humid Tennessee morning when the two runaways boarded a packed Greyhound bus bound for New York State. Azalea Lehndorff, then 14, and her 16-year-old sister, Sarah, had begun making plans to run away from home the moment their parents picked them up from Union Springs Academy and set off for the backwoods of Tennessee.

It had taken the sisters months to persuade their parents to let them attend the boarding school for a semester. They had gone so far as to steal their mother’s address book and write to 90 of her friends, explaining their goal of acquiring a high school education and asking them for the money to pay for it.

Now, plucked from her dream school, Azalea Lehndorff was determined to honor the commitment of those donors and graduate from the academy—with or without her parents’ blessing. “Even though we were sitting on the floor for the first section of the [bus] journey, I didn’t care,” recalls Lehndorff, now 25. “We were moving. We were moving away.”

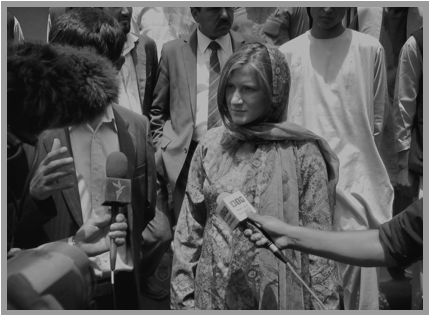

From this inauspicious beginning, Lehndorff’s travels eventually brought her to Lacombe, Alberta, Canada, where she graduated from Canadian University College. For the past two years, she has been a project manager with A Better World, an international development organization based in Lacombe. In 2009, Lehndorff launched the 100 Classrooms in Afghanistan project. Its goal is to provide much-needed facilities that will help to improve the quality of education for Afghan students and give girls a better chance at finishing high school. Her commitment to improving girls’ education was one of the reasons she was named Red Deer (Alberta) Young Citizen of the Year for 2011.

In Tennessee, when Lehndorff was eight years old, her family moved into a home with inside walls “constructed” of cardboard. But what really stands out for Lehndorff is the snakes: “One day, Mom was going to sit down on her bed and put her socks on when she turned and looked first. It was getting dark and we didn’t have electricity. Thankfully she was able to see that there was a snake coiled up on the bed.” Another time a rattlesnake greeted Lehndorff as she walked into the kitchen. They made the best of the situation—painting the cardboard walls white to brighten up the rooms, using a bucket and pulley system to remove the rodents in the well, and cleaning the junk out of the yard to make the place more liveable. “These experiences taught us to adapt and make the best of less-than-ideal situations,” says Lehndorff.

One saving grace was that their parents sold books. That ad hoc library, with the stories of Abraham Lincoln, Florence Nightingale and others, fueled Lehndorff’s interest in medicine and reinforced the growing feeling that her life was far from normal.

Lehndorff’s steely determination and her uncanny knack for persuading people to support her goals were forged by the teenage struggle to get out from beneath her parents’ thumb. Hostile to education and living the life of vagabonds due to her mother’s paranoia and her father’s inability to prevent this lifestyle because of his own severe health problems, Lehndorff’s parents had moved 26 times and lived in 11 states by the time their daughters were making plans to run off for good. Sometimes, the family would pack up in the dead of night and drift away without telling anyone that they were leaving. There was no guarantee that the home awaiting them would have electricity or running water. Once they lived in an old Winnebago RV in Ohio; another time, in West Virginia, home was a hunting cabin with a hand-pump well and no phone or electricity. The girls read in the evening by the light of kerosene lanterns.

But Azalea would need to graduate from an accredited high school to have any hope of attending medical school. Knowing that this was unlikely to happen if she stayed in Tennessee, Lehndorff called around, scoping out the fastest way out of town. When her parents caught wind of what she was up to, her mother called the phone company and had the service disconnected. Undeterred, Lehndorff made calls on the sly using the phone at a nearby nursing home. By the end of the week, she had persuaded a neighbor to drive the sisters to the bus station and pay for the tickets back to New York. When they arrived back at the Academy, the girls’ English teacher allowed them to live in her basement.

After graduating from high school, Lehndorff enrolled at Canadian University College. At one point she worked six jobs on campus to pay for tuition and make ends meet. “Honestly, I had no social life the first couple years,” said Lehndorff. “People didn’t even know I was going to school there.”

Lehndorff was inspired to help educate girls in Afghanistan while reading the now-embattled author Greg Mortenson’s book Three Cups of Tea. Before she had finishing reading the best-seller, Lehndorff, who had recently begun running marathons, had decided to run across Canada to raise money for the cause.

“I didn’t know how to raise money, but one thing was certain,” said Lehndorff. “I knew that education is a gift. I knew I was blessed, and I became determined to pass that gift on, to reach out to other young girls like me who also have dreams for their future. I decided to run because that is what I knew how to do.”

Lehndorff told only a few select people about her plans out of fear they would think she was crazy or, worse, try to squash her dream. But eventually, she pitched the idea to Eric Rajah, co-founder of A Better World. The proposal put Rajah in an awkward position. On one hand, Lehndorff was clearly inspired, so Rajah said he was careful not to discourage her. On the other hand, while many passionate, enthusiastic young people had approached him with project ideas since he began doing international development in the early 1990s, few of them had the commitment and determination to see the project through to the end. A Better World was not in a position to take over a project of such a magnitude in such a challenging region if she bailed on it, he said.

Lehndorff never bailed, although her fundraising plans changed radically over the next year or so. After meeting with Rajah, she persuaded a dozen or so friends and fellow students at Canadian University College to help her organize the run across Canada, dubbed Freedom Run 5000.

“Nobody ever stopped and said, ‘This is unrealistic.’ They really could have,” said Lehndorff. “That’s the thought that was running through my head, but I . . . didn’t want to make it look like I didn’t have confidence in what I was trying to propose.”

By January 2010, Lehndorff had scaled back her ambitions. Rather than run across Canada, she proposed running from Calgary to Edmonton. Two volunteers with A Better World, Cindy Wright and Julie Stegmaier, offered to help her organize it. After meeting with an experienced long-distance runner about the project, Wright and Stegmaier realized there were sizeable roadblocks standing between Lehndorff and her dream. Running from Calgary to Edmonton would require hundreds of volunteers, police escorts, medical personnel, support vehicles, time and money. Lehndorff also needed permission from Transport Canada to run on Highway 2, which had been denied, as well as approval from any community she planned to run through along the route, they learned. The women invited Lehndorff to dinner to give her the bad news.

“Julie and I were just crushed and were not looking forward to meeting Azalea for dinner,” said Wright, who began volunteering with A Better World after she and her husband, Richard, made their first trip to Kenya with the group in 2004. “Now we were going to be the dream squashers! However, once we got over our nervousness and talked frankly with Azalea about this run, we all realized that it was better to scale back a bit. . . .”

Though Lehndorff was disappointed, by the time the women left the restaurant that night, she had already come up with the idea of organizing shorter runs in central Alberta communities.

“I was so impressed with her in that she did not get discouraged or want to give up,” said Stegmaier, donor relations coordinator with A Better World. “She just thought of a new idea and started to make it happen immediately.”

The first Freedom Run took place in Red Deer in June 2010. It raised $5,000. A subsequent run in Lacombe raised $25,000. Runs have taken place in British Columbia and Saskatchewan as well. It is set up so anyone with the ability to organize events can start a Freedom Run in their community.

While a friend busied herself back home organizing the first Freedom Run, Lehndorff visited Afghanistan for the first time in May 2010. By the end of the trip, the goal of building 100 classrooms (approximately 12 schools), “a goal that once seemed insurmountable now hardly seemed worth the effort because the need was so great,” she said. Throughout that trip she had seen haunting images, the scars of war. She saw children who had stepped on landmines and now must live the rest of their lives missing a limb, fields filled with tanks from the time of the war with the Soviet Union in the 1980s, thousands of students in one school after another who sat on the dusty ground that served as their classroom, anxious to learn, but without even a basic school building with desks and supplies. She learned that, during the Taliban regime, girls and even in many cases boys did not have a chance to go to school. The enrollment had increased from 100,000 boys in 2001, when the Taliban lost control of Kabul, to over 6 million students (one third of whom were girls). How could a government that struggled to pay its workers invest in the construction projects needed to educate its young generation? How would parents commit to ensuring that their girls and boys go to school when the school was under the trees in the open air without books and facilities? How would their children be prepared for the Grade 12 exam that qualifies students to attend university? These issues swirled in Lehndorff’s mind as she thought about the small scale, yet seemingly overwhelming goal she had set—to build 100 classrooms so girls and boys would have the opportunity that they deserve, a basic human right: education.

That feeling of hopelessness became acute as the team was returning from a daytrip to some villages near the Salang Pass. As the team’s vehicle wove its way through Kabul’s dry, dusty streets, it began to rain. Lehndorff watched children play soccer and fly kites in a barren brown field next to the road before closing her eyes. Seeing the children, whose hopes and dreams must be tempered by the reality that war has brought upon their country, Lehndorff was desperate to conjure up a glimmer of hope that would motivate her to stick with her classroom project—to focus on making a few children’s dreams a reality.

When she opened her eyes again, there was a rainbow over the dusty and barren city of Kabul. Lehndorff said she didn’t know the answers to questions that had been nagging her since she touched down in Afghanistan, but she was determined to see her project through to the end. “In the Bible, [a rainbow] is a symbol of a promise and hope,” she said. “And that’s what it meant to me. A rainbow never shows up until there is at least a glimmer of sunlight, when the storm is ending. I thought of the people of Afghanistan, how much they hope for the end of the long storm of war that has bereft so many of those they love and the life that they had hoped to lead. I realized that the children deserve any effort that is made to improve their chances for a better and more peaceful future.”

Since that trip, Lehndorff has traveled to Afghanistan three more times, and spent three months living in Kabul. During the winter months in Afghanistan, life becomes especially difficult for the returnees (coming back from Iran and Pakistan) and internally displaced Afghans, who have moved from their homes due to ongoing conflict in their villages and are now living in informal settlements. Lehndorff visited one such settlement in January 2011. Eighty-eight families lived there, most of which earned only $12 per day. In one such family of twelve children, only two were able to attend school while the others went to the market to collect plastic to burn inside the tent that is their home. They also collected cans for the deposit—that family’s only source of income. Last winter more than 25 children froze to death.

After spending a few hours walking from tent to tent and talking with the inhabitants, Lehndorff made a plan to have a truckload of coal delivered to this camp. Each family would receive a $33 bag of coal that would last for one month. When the truck arrived for delivery, mothers, fathers, and children crowded close to the roped partition the staff had erected. The families waited anxiously to receive their bag of coal that meant a few warmer days ahead for their children.

This is a short-term relief effort, yet these families long to settle down on their own land. They want their children to go to school. They want to be certain that they can feed their children. They want the same things that families would seek anywhere in the world. The challenges that these families face are overwhelming. They survive from one day to the next, hoping for a brighter future that seems far from their grasp. “Generally, when talking to each person in the camp, I did not sense hopelessness, but a desire for change,” Lehndorff said of her visits to the informal settlement in Kabul.

The people have elected a leader, who they say has been in charge for the past five years. A strong woman who came back to Afghanistan from Pakistan where she and her family lived in a refugee camp, she listens to the peoples’ grievances and solves disputes. She carries a leather whip. When government or aid agencies visit the camp, she communicates with them, fills out any required paperwork, and provides basic information about the families living in the camp.

After spending two hours walking from one tent to the next, talking with the families, Lehndorff’s toes had become numb, as the ground was covered with snow. “At one tent, I was invited inside,” she explains. “I mentioned that my feet were cold and before I could object, I was seated on a carpet on the ground while the woman of the house rubbed my feet. She even offered me tea. When I was walking away from that home, I shed a tear, thinking of my own warm bed and the many things that I have, and wondering if I would be so anxious to give if I were in that family’s situation.” Lehndorff’s commitment to serving the Afghan people comes from a belief that they deserve the same privileges that she has experienced. She is drawn back by their kindness and hospitality.

Two years after the beginning of this journey with A Better World to advocate for the children of northern Afghanistan, more than $500,000 has been raised, four schools have been built (32 classrooms), and over 8,000 students have benefitted from the improved facilities. This success has been possible because many individuals, schools, churches, and community groups have contributed time, effort, and financial support towards this goal. In 2010-2011, Lehndorff spoke to over 80 different community groups, schools, and churches, asking them to join her in the effort to bring better educational opportunities to both girls and boys in Afghanistan.

Thanks to Elmer Gish Elementary School, a girl’s high school in Afghanistan will have one new classroom in 2013. A small elementary school in Victoria, British Columbia, Lakeview Christian School, worked with two local Seventh-day Adventist churches and raised over $8,000 in 2010. Their classroom was completed at Arab Khana High School in 2011. This year, they are fundraising again. In Regina, Saskatchewan, teachers and administrators of the Regina Catholic School Division planned a run, Moving in Faith, to involve over 600 parents, students, and members of the community to raise funds to build a classroom. That classroom was completed in June 2012 as part of the eight-classroom building constructed at Kinara Secondary School. Fraser Valley Adventist Academy planned a Freedom Run event for their community, and their classroom was completed in June 2012.

The four new schools that stand today in Sheberghan, Afghanistan, in place of outdoor classrooms, tattered tents, and dilapidated buildings are there because individuals chose to reach across the world and invest in a more peaceful future for Afghanistan and improved lives for thousands of children.

Lehndorff remains determined to finish the project, which has had its fair share of ups and downs. During the June 2012 trip, during which a third school was opened in northern Afghanistan, Lehndorff visited a girl’s high school in a rural village. The current mud structure was built by parents, but the school has now spilled out into the school-yard where tents are set up for the younger students. Students showed Lehndorff the “library,” a six-foot-square mud building that, they explained, “stays locked in the warm weather because the snakes live inside.” A Better World hopes to build a brand new school with eight classrooms, a lab, a non-snake infested library, and enough space for the now 600 girls who attend. “It is relatively cheap to build a large school in Afghanistan that has electricity in every room and is made with quality materials. The entire structure is approximately $100,000 (US). It’s a worthwhile investment when you consider the thousands of students who will benefit over the upcoming years,” Lehndorff explains. There are two such girl’s schools where the communities are waiting and have already donated the land for a new girls’ school to be built.

Along with successes have come unexpected challenges. Although obstacles are expected when working in a country such as Afghanistan, the disappointments have not originated from within Afghanistan, but from without. The Mortenson scandal in early 2011 hit Lehndorff particularly hard because she had been so inspired by Three Cups of Tea. Learning that Mortenson may have embellished or fabricated parts of the book and used charitable donations to support his lifestyle made her feel “intensely disappointed.”

In the months since the scandal broke, Lehndorff has re-evaluated Mortenson’s impact on her life. “He’s not a villain. It’s just that his humanness caught up with him and, thankfully, he was called to task for it,” she said. “I was really blessed to have the opportunity to go to Afghanistan, because I think that’s what gave me my own experience and the resolve (to continue).”

Lehndorff is thankful to have been mentored by Eric Rajah, A Better World’s founder, along with many others within the organization, including Pastor Ron Sydenham, the Chair of the Board. Lehndorff believes that if she had not been given the opportunity to travel to Afghanistan, her passion would have been overcome by fear of the unknown and her commitment would have wavered. She points to that first trip in 2010, right after her graduation from university, as a turning point, “a perspective changing experience, the impact of which has inspired me to continue, to move forward as an advocate for the poor in Afghanistan.”

Knowing that other students in North America and throughout the world desire to make the world a better place, Lehndorff wants them to have the same opportunities that she has enjoyed—the opportunity to be mentored, and to travel to communities where the rural poor live. More Christian young people are seeing humanitarian work as part of the mandate given by the great Servant, Jesus Himself.

While Matthew 25 inspires service, the opportunity to travel, to see the needs of the people, and to learn about how to help without hurting them informs service. “Not only can we feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and generally seek to bring dignity to people who may not be physically naked, but who lack the basic ability to provide for their families and send their children to school, we can do it in a way that empowers them.”

Lehndorff’s ability to rise above challenges has inspired other A Better World volunteers. According to Wright, Lehndorff has taken the organization to a new level. Watching her brainstorm ideas with other students as part of A Better World’s newly developed student division is a wonderful thing to see. “She is very hard working and once she sets her mind to something, believe me, it will happen!” said Wright.

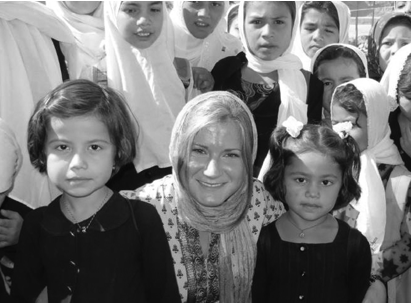

A decade after running away from home, Lehndorff is passionate about giving the gift of education—which she struggled to receive—to children in Afghanistan. But sometimes the gift comes from the children. During the first opening ceremony, a young girl in Grade 6 approached Lehndorff and handed her an original drawing—a dove in flight and holding a pen. “It was profound—a young girl who has never known a peaceful Afghanistan, imagining peace and seeing it connected with education.”

Looking back over the past 10 years, Lehndorff points to individuals along the way who reached out and played a part in giving her the gift of education. She admits, “Although I put every effort to get through school, both academically and financially, it never would have been possible without individuals who went outside of any obligation and reached out.” She remembers Penny in New York, whose home became a place to go on Christmas vacations; the Assembly of God pastor and his wife who treated the sisters like their own children; the English teacher and her family who offered their basement room as a place to stay during the summers; the encouragement and friendship of a family in Ontario who added Lehndorff as their honorary fifth child; Rajah, who has been a mentor and teacher; and many others.

“It is a simple idea. I have been blessed. A gift has been given to me. I was born in a place where opportunity is not an exception, but the rule. What really motivates me to want to reach out and pass that gift to others is a sense of gratitude and a feeling of indebtedness.” The mentorship and opportunities for growth that have been offered by the College Heights Adventist Church, professors and students at Canadian University College, and the most significant investment given by Rajah, who made the case to A Better World’s board for Lehndorff, a classmate, and two professors to travel to Afghanistan in 2010 for the first time despite the risk, are the reason for the success that the 100 Classroom Project has enjoyed. More than that, Lehndorff says, “this opportunity has changed my life. It has given me a passion for service. I believe that one of the greatest ways that we can share the love of Christ in a hurting world is through humanitarian service in our local communities and throughout the world.”

In recognition of the role that mentorship and travel opportunities have had in shaping her passion for service, Lehndorff started working with A Better World in 2011 to launch a student division. Called Tomorrow’s Edge, it is designed to offer the same mentorship and travel opportunities that she and other students have found so inspiring. This year, Mikelle Wile, a high school student, mobilized her classmates and teachers at her school in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, to raise $20,000 to fund a school in Kenya. Mikelle then traveled to Kenya to attend the grand opening. Another student, Julie Anderson at the University of Lethbridge, gained support from the university president, her professors, and fellow students, and raised $8,000 by planning a fundraising event on campus. Sixteen public high schools have participated in fundraising and travel with A Better World. “Students today want to make the world a better place. They want to put their faith into action. They are just looking for an opportunity.”

Azalea Lehndorff is attending the University of Alberta, working towards an M.P.H. (Global Health), which she hopes will enable her to continue her work with communities and to address poverty, inequity, and other determinants of health. She is based in Edmonton, Alberta, and continues to work towards reaching her goal to build 68 more classrooms in Afghanistan. Azalea Lehndorff can be reached via e-mail at alehndorff@abwcanada.org. For more information about A Better World, see their website: www.a-better-world.ca. Learn more on Facebook: 100 Classroom Project.

Cameron Kennedy is the Red Deer Life editor and a reporter at the Red Deer Advocate. He has travelled twice with A Better World to Afghanistan.

Rajiv Emerson works for Advanced Systems as an IT Customer Support Specialist and volunteers for A Better World in social media and communications.