Abstract: In this article, the author suggests midcareer is a central but transitional season in a Christian leaders’ life-course. During this season, the Lord seeks to bring clarity to, and integration between, the leader’s calling as a citizen of the Kingdom of God, the leader’s personal identity as united with Christ, and the leader’s occupation within his or her organization. After proposing a conceptual framework for the experience of midcareer, the author discusses common themes, challenges, and opportunities of “middlescence” (Morison, Erikson, & Dychtwald, 2006), which exist on a continuum from “burning out” on one end to the “sweet spot” of ministry on the other. This article concludes by proposing a series of developmental assignments midcareer Christians could employ as they move toward fruitfulness.

Keywords: midcareer leadership; midlife; leader development; midlife crisis

Introduction

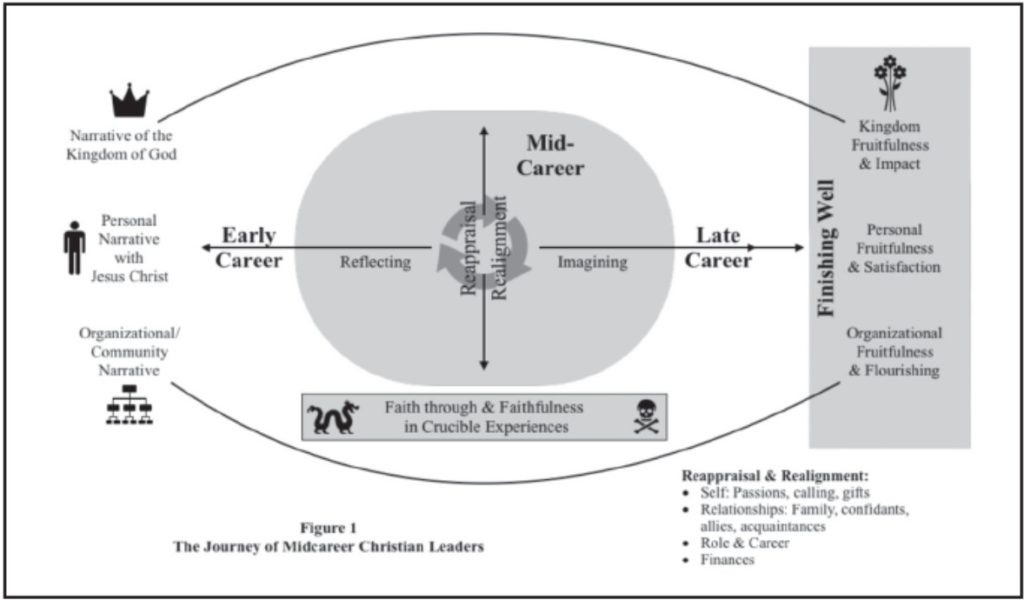

“Like adolescence, middlescence can be a time of frustration, confusion, and alienation but also a time of self-discovery, new direction, and fresh beginnings,” observe Morison, Erikson, & Dychtwald (2006, p. 80) about the experience of midcareer leaders; those who are midcareer are typically people between 35–50 years old who have worked in their careers for at least ten years.1 Even more so, midcareer Christian leaders not only face these same challenges and opportunities, but seek to envision how the remainder of their earthly lives fit uniquely into God’s overarching redemptive plan. Midcareer is a central, but transitional, season in the life-course of a Christian leader, when the Lord particularly seeks to bring clarity to and integration between the leader’s calling as a citizen of the Kingdom of God, the leader’s personal identity as united to Christ, and the leader’s occupation within his or her organization.2 In this article, I discuss this assertion by first suggesting a thematic framework for conceptualizing the experience of the Christian midcareer leader (see Figure 1). Then, I will identify and describe the main themes of midcareer before discussing the common challenges and opportunities for midcareer leadership development. Finally, I will conclude by creating four midcareer leadership development assignments, which Christian leaders could use to assist them in their Journey toward Christlikeness and vocational fruitfulness.

A Conceptual Framework for Midcareer

Figure 1

A Conceptual Framework for Midcareer

Figure 1 presents my conceptualization of the experience of the Christian midcareer leader.3 In the diagram, I attempt to visualize the Christian’s experience of midlife as that particular season in the adult life-course when the Lord seeks to clarify and integrate the leader’s calling as a citizen of the Kingdom of God (see top arch), the leader’s personal identity as united to Christ (see center line), and the leader’s occupation within his or her organization (see bottom arch). The goal of the Lord’s clarifying and integrating work in the leader centers on finishing well, characterized by Kingdom, personal, and organizational fruitfulness at the end of the leader’s life. The midlife Journey toward that destination involves reappraisal and realignment of various aspects of personal, familial, and professional life through prayerfully and communally reflecting on early career and creatively imagining the future. Furthermore, the Lord also uses the leader’s pilgrimage through crucible experiences (Bennis & Thomas, 2002), those experiences of suffering and heartache, to refine and shape the leader for greater future impact (Clinton, 2012). In summary, this framework for conceptualizing the midcareer experience of the Christian leader seeks to hold together three questions:

- How do I fit into Christ’s narrative of redemption as a uniquely gifted citizen of the Kingdom of God?

- What is my particular narrative identity as one united to Jesus Christ?

- How does my personal narrative resonate (or not resonate) with the organizational narrative in which I currently work?

The Main Themes of Midcareer

Within this larger framework for the Christian leader’s midcareer experience, at least three primary themes emerge. First, midcareer is a central but transitional space within the adult life course (Lachman, 2015). Lachman (2015) summarizes,

We characterize midlife as pivotal in terms of (1) a balance and peak of functioning at the intersection of growth and decline, (2) its linkage with earlier and later periods of life, and (3) as a bridge to younger and older generations . . . This perspective takes into account that midlife plays a central role in the life course of the individual and also at the family and societal levels. (p. 331)

It may not be an exaggeration to assert that midcareer remains the most crucial season of life for Christian leaders, even as it remains a transitional bridge between early and late career and between the younger and older generations. Drawing from early-career mistakes and lessons, midcareer leaders can wisely plant seeds for late career fruitfulness. They also may better align their sense of narrative identity with their God-given vocation for the Kingdom of God and in their organizational life. Moreover, society, families, and organizations rely heavily upon midlife adults. This group has enough life and work experience to draw upon to make more meaningful contributions, coupled with enough energy to work efficiently and productively. If parents, they have a primary role in raising children, and they increasingly become the ones to train or mentor early-career coworkers.

While midcareer persists as a central space within the life course, it is also a season of heightened self-reflection and existential questioning (as depicted by the reflexive circle in Figure 1). In his seminal article, “The Midcareer Conundrum,” Kets de Vries (1978) reflects,

When people reach the midpoint of their lives a number of changes occur. Although the environment still seems full of opportunities, the preoccupation with inner life become more important. There is a greater sense of introspection, self-evaluation, and reflection. We notice an existential question of self, values, and life. (p. 47)

For maturing Christian leaders, this existential questioning tends to focus on questions about vocation. Questions such as the following are common:

- Is this what the Lord wants me to do for the rest of my life, given my God-given gifts and talents?

- How can I have a more significant Kingdom impact in the world for Christ’s glory?

- How can I better pass on my faith to my children and/or the younger generation?

- How is Christ forming my identity so that I can be faithful and finally fruitful for the rest of my earthly life?

These types of questions, along with this process of introspection and self-evaluation, follow the two pathways of reflection and imagining (see Figure 1). In reflection, midcareer leaders look back over how the Lord has provided for and shaped them during their early career. They take stock of the mistakes they have made. They review what aspects of life and work ignite their passions. Through these reflections, midcareer leaders come to more clearly understand and accept whom the Lord has created them to be. With a clearer vision, they can imagine the future, creatively envisioning what the Lord might be calling them to accomplish for His Kingdom. This imaginal work is not just wishful thinking but has historical roots in self-reflection. Based on their clearer self-knowledge at midlife, they can envision real possibilities for significant Kingdom impact and long-term fruitfulness with the Spirit’s help.

As midcareer Christian leaders gain better clarity about whom the Lord has created them to be, they must also learn to embrace their being in Christ before their doing for Christ. This is the third central theme of midcareer leadership. In his leadership emergence theory, Robert Clinton (2012) discusses a change that needs to occur between the “Ministry Maturing” and “Life Maturing” stages of a Christian leader’s midcareer. In early ministry

God is primary working in the leader. Though there may be fruitfulness in ministry, the major work is that which God is doing to and in the leader, not through him . . . . God . . . is trying to get the leader to see that one ministers out of what one is. God is concerned with what we are. We want to learn a thousand things because there is so much to learn and do. But He w1ll teach us one thing, perhaps in a thousand ways: “I am forming Christ in you.” It is this that w1ll give power to your ministry. [Later ministry] w1ll have this “you-minister-from-what-you-a re” emphasis. (p. 27-28)

Another way to express Clinton’s observation is that midcareer ministry leaders must learn to become a “Mary” before they continue to work as a “Martha” (Luke 10:38-42). They must first be with Jesus, metaphorically sit ting as His feet in love before serving in His name. If Christian leaders do not learn to rest in their union with Christ (Rom. 6:5-12) and practice daily communion with Him (Luke 10:39) during midcareer, they will inevitably burn out and exit Christian ministry altogether. Leaders cannot produce the fruit of the Kingdom in their personal, familial, and organizational lives if they do not abide in Christ (John 15).

I have discussed the three primary themes of midcareer leadership, including the pivotal role it plays in the human life-course, the self-reflective and introspective nature of the season of life, and the necessity of inculcating a posture of communion with Christ. In the next section, I will present common challenges and opportunities for the Christian midlife leader.

Common Midcareer Challenges and Opportunities

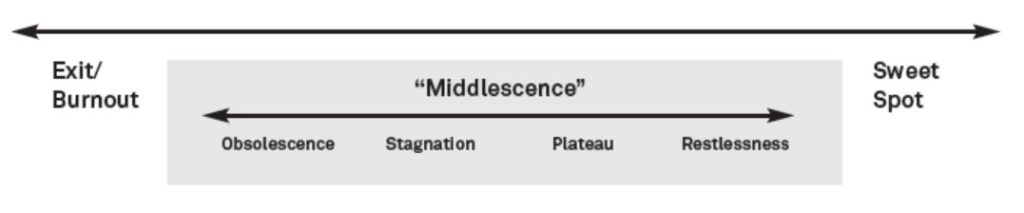

Common midcareer challenges and opportunities exist along a continuum (see Figure 2), from exiting or burning out of ministry altogether to operating within a God-given leadership sweet spot. Between these two poles is the broad experience of “middlescence,” which Morison, Erickson, & Dychtwald (2006) describe as “midcareer restlessness” (p. 79). This restlessness can have a negative or positive connotation. Middlescence can be a time of “frustration, confusion, and alienation” and/or “self-discovery, new direction, and fresh beginnings” (p. 80). In my conceptualization, I view the experience of middlescence as negative based on the extent to which midcareer leaders feel “stuck” and left behind. In contrast, I consider it positively based on the degree to which leaders feel challenged and hopeful for the future.

Figure 2

The Experience of Midcareer Leadership: Challenges and Opportunities

Common Midcareer Challenges

There are several common challenges of midcareer that can push leaders toward the continuum’s negative side (see Figure 2). First, midlife is often the period of heaviest responsibility within the adult life-course. “Midcareer workers are sandwiched between commitments to children and parents, often at the same time that their work responsibilities are peaking” (Morison, Erickson, & Dychtwald, 2006, p. 81). Trying to find a healthy ministry/life balance can be a daunting task, as organizations increasingly rely upon midcareer workers to take up leadership responsibility based on their early-career experience. Conversely, if familial life demands are significant, this can diminish energy for the leader in their vocational life, contributing to work stagnation or plateauing.

Second, because of the increasingly fast-paced knowledge economy, skills obsolescence exists as a real challenge for midcareer leaders (Kets de Vries, 1978; Morison, Erickson, & Dychtwald, 2006). Depending upon the vocational context, what leaders learned in college and practiced in early-career may not sustain them during midcareer and into late career. Diligence in their jobs may not result in forward movement or promotion without upgrading their skills and committing to life-long learning. Even for leaders in Christian ministry, where the eternal gospel sustains them, the speed of cultural change can leave them unable to wisely apply the gospel to the culture without a continued commitment to spiritual growth and increasing their cultural intelligence.

Third, stagnation or plateauing in midlife can result from financial challenges and constraints. While worker income normally increases between early-career and mid-career, the cost of living also increases. For married leaders with children, who are often raising children throughout the course of midlife, the even higher cost of living associated with children’s care, activities, and schooling/college can constrain of the leaders’ vocational lives.4 If a chronic medical condition also exists for leaders or their families, it further complicates leaders’ sense of stagnation. Often midcareer people remain committed to their organization or ministry because of the salary and benefits it provides, while feeling “stuck” and stagnated in their sense of personal vocation.

The previous three common challenges of middlescence may combine and help to explain the fourth negative experience of midlife. Over the adult life course, researchers observe the lowest life satisfaction levels during the middle years, with young adult and senior adults tending to be happier (Lachman, 2015).

Many studies have documented that happiness and life satisfaction reach their nadir at midlife . . . , often called the u-ben. . . . . There is indeed a fairly consistent finding that the middle years, usually between age 30 and 50, show the lowest level of life satisfaction or happiness. (Lachman, 2015, p. 329)

However, this observation needs to be qualified in two ways. One, “the age differences in happiness are nevertheless very small, on the order of .2 to .7 on a 10-point scale” (Lachman, 2015, p. 330) compared to earlyand late-career workers. Second, the stereotypical “midlife crisis,” which I associate with exit/burnout on the midcareer continuum (see Figure 2), is rarer than the popular stereotype, with only ten to twenty percent of adults reporting such a crisis (Lachman, 2015, p. 331).

Fifth, crises and conflicts can commonly exacerbate the u-bend phenomenon of midlife, which, when viewed redemptively, can be described as “crucible” experiences (Bennis & Thomas, 2002; Clinton, 2012; McAdams, 2014). In their classic article, “Crucibles of Leadership,” Bennis & Thomas (2002) describe the crucible experience as a

trial and test, a point of deep self-reflection that forced [leaders] to question who they were and what mattered to them. It required them to examine their values, question their assumptions, hone their judgment . . . .Leadership crucibles can take many forms. Some are violet, life-threatening events. Other are more prosaic episodes of self-doubt. But whatever the crucible’s nature, the people we spoke with were able to create a narrative around it, a story of how they were challenged, met the challenge, and became better leaders. (p. 40)

From a Christian perspective, Clinton (2012) discusses the common ministry leadership crises and conflicts in the “ministry maturing” and “life maturing” phases of leadership development associated with midlife. Crisis and conflict are process items that the Lord uses to refine the character of the leader with the “result that the leader experience[s] God in a new way as the Source of life, the Sustainer of life, and the Focus of life” (Clinton, 2012, p. 143).

Common Midcareer Opportunities

In contrast to the common midlife challenges, several opportunities push leaders toward the positive side of the middlescence continuum (see Figure 2). First, as previously hinted at, leaders in midcareer can hit their vocational productivity peak (Kets de Vries, 1978; Morison, Erickson, & Dychtwald, 2006). In my conceptualization, they can achieve a vocational “sweet spot,” where their sense of God-giving calling, life experience, and skillset match their organization’s challenges, resulting in fruitful activity and personal satisfaction. Unfortunately, the stereotypical narrative of “midlife crisis” (Lachman, 2015) overshadows this positive counter-narrative of midcareer.

Secondly, midcareer leaders push toward their sweet spot as they embrace “generativity.” Erik Erikson (1950) famously described middle adulthood as the stage of “generativity versus stagnation.” Generativity refers to adults’ need to create or nurture things that will outlast them, often by having children of their own or by mentoring younger adults. They want to have success in creating change that benefits others and the world. Christians, especially, are concerned with generativity because it is consistent with the biblical call to discipleship and passing on the faith of Christ to others (Matt. 28:18–20; 2 Tim. 2:2). Building upon Erickson’s work and based upon his own research, McAdams (2014, p. 63) argues that “highly generative adults in American society tend to construct their lives as narratives of personal redemption.” He identifies four common redemptive narratives: atonement (a movement from sin to salvation), upward social mobility, liberation from oppression, and recovery (p. 64–65). For Christian midcareer leaders, the continual and reflective embrace of the Lord’s redemptive work in their lives provides fuel for crucible experiences and moves them toward their vocational sweet spot.

A third opportunity for midcareer leaders centers on their capacity to reflect upon their early career to effectively make needed changes. This opportunity expresses one of midlife’s main themes: it is a season of heightened self-reflection and existential questioning (Kets de Vries, 1978). Further, as presented in my framework for conceptualizing the journey of midcareer (see Figure 1), midlife can become that particular season in the adult life course when the Lord seeks to clarify and integrate the leader’s calling as a citizen of the Kingdom of God, the leader’s personal identity as united to Christ, and the leader’s occupation within his or her organization. After ten or more years of ministry, these leaders have enough life, work, and ministry experience to draw upon to understand themselves better and rely upon God’s goodness and providence more deeply. They have sufficient vocational history and personal history of the Lord’s sustaining grace that they can more clearly embrace and articulate their weaknesses, limitations, passions, and strengths. Often, they have a more refined sense of how to trust, pray through, and act upon their sense of intuition—that pre-rational feeling, not yet able to be verbally articulated, that something is either “not right” or is “just right.” All of this reflective capacity makes midcareer a ripe time for life-style adjustments, career changes, and vocational tweaks, so that leaders can move toward better alignment with their God-given vocational “sweet spot” within his Kingdom.

In this section, we have examined the common challenges and opportunities of midcareer Christian leaders. In contrast to early and late career leaders, midlife leaders typically face several challenges, including heavier responsibilities in work and family life, the possibility of skills obsolescence, tighter financial constraints, lower levels of life satisfaction, and life-altering crucible experiences. However, they also can take advantage of some of the unique opportunities usually afforded them in midlife, including hitting their peak of vocational productivity, embracing generativity as they mentor and disciple younger workers (and their children), and discovering their “sweet spot” within their God-given vocation in His Kingdom, through prayerful and wise self-reflection. Next, I will build upon this study to present some questions that midcareer leaders can use to assess their particular situation before suggesting several development assignments they can explore.

Reflection Questions for Midcareer Leaders

As midcareer Christians reflect upon their personal identities in Christ, their vocation within the Kingdom of God, and their occupation in their organization or ministry, the following questions may be helpful for reflection:

- Reflecting upon your early career experiences, how has the Lord provided for you? How has He sustained and matured you through crucible experiences? How has He particularly gifted you for life and ministry?

- Read Luke 10:38–42. Do you identify more with Mary or Martha? Why? What would it look like in your life and occupation to be with Jesus Christ before doing for His Kingdom?

- Review Figure 2. Where would you locate yourself on the continuum? Why?

- If you are considering a career change, what would it be? Based on your God-given gifts and passions, what would be your dream job or ministry?

- If you are currently experiencing a life transition, what emotions are you experiencing and how are you managing those emotions (particularly the emotion of loss)? How is the Lord sustaining you through the transition?

Midcareer Developmental Assignments

Based on the previous self-assessment questions, I will present four developmental assignments that Christian leaders could use for personal and vocational growth in Christ. For each assignment, I will briefly describe the activity, why it could be helpful, and suggest what follow-up and feedback might help the leader based on the activity.

A “Provision of the Lord” Prayer Journal

As midcareer leaders reflect upon their early careers and life experiences to better understand themselves and imagine the future, a crucial task is to remember the Lord’s goodness by considering their personal histories of God’s provision. One way to do this is to write a “Provision of the Lord” prayer journal.5 In this journal, leaders can remember and record all instances in their adult life where the Lord unexpectedly provided for them in some meaningful way. They can record significant answers to prayer, especially those ways the Lord sustained them through crucible experiences. This assignment is helpful because it cultivates faith’s active remembrance and can provide encouragement and perspective to midcareer leaders who feel stuck in middlescence or are uncertain as to what Christ is calling them next.

In follow-up to this exercise, I would suggest two things: 1) view this journal as an ongoing project. Leaders can continue to record new provisions of the Lord and answers to prayer in it. They can periodically go back and read through it every few months. 2) Leaders can share some of the important insights they have gleaned from the exercise with their closest friends, small group, or leadership team, to testify to the Lord’s goodness. Such times of verbal, communal sharing further embed faith in the heart.

The Habit of a Personal Devotional Life

As Clinton (2012) wisely advocates, God is most concerned with “forming Christ in us,” rather than what leaders do for Christ. “It is this that will give power to your ministry. [Later ministry] will have this ‘you-minister-from-what-you-are” emphasis’” (p. 28). Both in my own midcareer life and in other Christian leader’s lives, I have observed that it is far too easy to ignore personal devotional life with Jesus Christ while focusing instead on ministry tasks. Put differently, ministers love to do like “Martha” without also being like “Mary.” This orientation will eventually result in ministry exit or burnout. If leaders wish to push toward the “sweet spot” of Kingdom ministry and finish well, an essential practice must be the discovery, cultivation, and habituation of a personal devotional life, outside normal ministry tasks. Leaders should seek to discern what sort of devotional practice works best for them, based on their season and rhythm of life and their God-given personality; these practices should at least include near-daily systematic Scripture reading, Scriptural meditation, and focused prayer, and weekly corporate worship, Christian fellowship, and Sabbath-keeping.

This assignment could take place over six months. The first two months could be the discovery phase when leaders try various devotional approaches and seek to discover what could work best for them.6 The middle two months could be the cultivation phase when they settle upon a plan for their devotional life and seek to practice it consistently. The final two months could be the habituation phase, when the goal is to allow the Holy Spirit to habituate the devotional activity, so it becomes part of the fabric of their lives. This assignment would help a spiritual director or older Christian mentor provide suggestions, encouragement, and accountability to assist leaders.

Reflective Reading and Group Discussion

Depending upon midcareer’s experiences, I would suggest two books for leaders to reflectively read and discuss in a season-of-life group. For leaders experiencing the obsolescence, stagnation, plateau, and restlessness of middlescence, I suggest they read Paul David Tripp’s (2004) Lost in the Middle: Midlife and the Grace of God. Tripp presents a “theology of uncomfortable grace,” in which the ever-present God sustains Christians through the crucibles of midlife, so that they do not get “lost in the middle.” For leaders who are considering or are already experiencing a vocational transition, I suggest they read Bridges & Bridges’s (2016) Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Transitions. The authors present how each of the three stages of any transition (i.e., “The Ending,” “The Neutral Zone,” and “The New Beginning”) can be understood and embraced healthfully.

Along with reading these books, I would encourage leaders to gather in a season-of-life group with six to eight other people (those who are generally having the same midcareer experiences) over about eight weeks. The goal of the group would be threefold: 1) to encourage one another about God’s goodness and work through the transitional season of midlife, 2) to communally process the emotions and challenges of midcareer from a Christian perspective, and 3) for participants to co-counsel one another with concrete suggestions for moving toward the “sweet spot” of vocation and ministry.

Vocational Assessment with a Career Coach

Even if midcareer leaders do not feel stagnated in their occupations or are not actively seeking a career change, midcareer constitutes an advantageous time for leaders to take a leadership strength or 360-degree leadership assessment, to be administered by a life/career/ministry coach.7 With enough early career work and life experience to draw upon, these assessments can be fairly accurate representations of leaders’ actual strengths. Moreover, a career coach trained to administer such tools can more effectually help leaders craft strategies and make career decisions based on their strengths and passions. Along with a coach, leaders should share the assessment results with their closest family and Christian community, beginning a prayerful discussion about how the Lord might be shaping their vocation in the world, for “in the abundance of counselors there is safety” (Prov. 11:14).

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that midcareer is a central, transitional season in Christian leader’s life course. It can be a unique season when the Lord seeks to bring clarity to and integration between the leader’s calling as a citizen of the Kingdom of God, the leader’s personal identity as united with Christ, and the leader’s occupation within his or her organization (see Figure 1). This occurs especially through the heightened self-assessment and existential questioning which leaders tend to engage in during midlife, as God desires to anchor them in their being in Christ before their doing for Christ. Throughout midcareer, Christian personal and vocational maturity normally occurs through the common challenges and opportunities of middlescence, which exists on a continuum from burning out to working in the “sweet spot” of ministry (see Figure 2). For midcareer leaders to move toward fruitfulness (with finishing well as their main goal), they should purposely engage in some developmental assignments. In conclusion, whatever their current experience of midcareer, Christian leaders can take encouragement from the scriptural promise that the God “who began a good work in you will bring it to completion at the day of Jesus Christ” (Phil. 1:6).

1 The literature defines midcareer in slightly different ways, depending upon whether the authors view it as an age construct (e.g. midlife; McAdams, 2014; Menon, 2015), a career construct (Kets de Vries, 1978; Morison, Erickson, & Dychtwald, 2016), or a combination of both (Ramo & Ibarra, 2008). While the literature seems to agree on the general beginning of midcareer at 35, authors mark the close of the season variously, between 50 and 59 years old. For the purposes of this paper, I define midcareer as 35–50 years old with at least 10 years of career experience.

2 I want to be careful to acknowledge that my view of midcareer leadership, while anchored In a larger theological vision of maturity In Christ, may be unique to the experience of (Western) professional class leaders. The experiences of midcareer and/or midlife may be very different for non-professional lass people and/or people from the Majority World.

3 Dr. Deborah Colwlll’s conceptual framework In the seminar, ”Midcareer Leadership Development,” at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, Deerfield, IL, Inspired significant parts of my conceptualization In Figure 1, especially the language of “reflection, reappraisal, and realignment.” She also suggested the categories of “self,” “relationships,”” role/career,” and “finances” In the reappraisal and realignment process, which she observed as main categories In the literature on midcareer.

4 I realize this observation is culturally based on a generalization of professional class people in the United States and may not be valid across cultures and socioeconomic classes.

5 This assignment was first suggested to me by my friend, Dr. Eric Brown, who began such a journal while he was in a major midcareer transition.

6 There are multitude of helpful resources to assist Christian leaders in personal devotionality. Among those that I have found most helpful are: Peter Scazzero’s (2017) Emotionally Healthy Spirituality; Tim Keller’s (2016) Prayer; Phyllis Tickle’s (2006a, 2006b, 2006c) three manuals of prayer called The Divine Hours, and The Valley of Vision: A Collection of Puritan Prayers and Devotions (1975). See also modern classics on the spiritual disciplines: Richard Foster’s (2018) Celebration of Discipline; Dallas Willard’s (1999) The Spirit of the Disciplines; and Donald Whitney’s (2014) Spiritual Disciplines for the Christian Life.

7Many helpful assessment options exist such as Rath’s (2007) StrengthFinders 2.0; Rath & Conchie’s (2008) Strengths Based Leadership; Brun, Cooperrider, & Ejsing’s (2016) Strengths-Based Leadership Handbook; The Career Direct® assessment by Crown Ministries; and Talentsmart’s Emotional Intelligence Appraisal® Multi-Rater and 360° editions.

References

Bennett, A. (Ed.). (1975). The valley of vision: A collection of Puritan prayers & devotions. Carlisle, PA: The Banner of Truth Trust.

Bennis, W. G., & Thomas, R. J. (2002). Crucibles of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 80(9), 39–45.

Bridges, W., & Bridges, S. (2016). Managing transitions: Making the most of change (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Brun, P. H., Cooperrider, D., & Ejsing, M. (2016). Strengths-based leadership handbook. Brunswick, OH: Crown Custom Publisher.

Clinton, R. (2012). The making of a leader: Recognizing the lessons and stages of leadership development (Revised and updated edition). Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

Crown Ministries. The career direct. Retrieved from https://www.crown.org/career/

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY: Norton.

Foster, R. J. (2018). Celebration of discipline: The path to spiritual growth (Special anniversary edition). San Francisco, CA: HarperOne.

Keller, T. (2016). Prayer: Experiencing awe and intimacy with God. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Kets de Vries, M. F. (1978). The midcareer conundrum. Organizational Dynamics, 7(2), 45–62.

Lachman, M. E. (2015). Mind the gap in the middle: A call to study midlife. Research in Human Development, 12(3–4), 327–334.

McAdams, D. P. (2014). The life narrative at midlife. New Directions for Child & Adolescent Development, 2014(145), 57–69.

Menon, U. (2015). Midlife narratives across cultures: Decline or pinnacle? In L. A. Jenson (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human development and culture: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 637–652). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Morison, R., Erickson, T., & Dychtwald, K. (2006). Managing middlescence. Harvard Business Review, 84(3), 78–86.

Ramo, L. G., & Ibarra, H. (2008). Leadership development during midlife: A turning point in career advancement. INSEAD Working Papers Collection, 36, 1–39.

Rath, T. (2007). StrengthsFinder 2.0. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

Rath, T., & Conchie, B. (2008). Strengths based leadership: Great leaders, teams, and why people follow. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

Scazzero, P. (2017). Emotionally healthy spirituality: It’s impossible to be spiritually mature, while remaining emotionally immature (Updated edition). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Talentsmart. Emotional intelligence appraisal® multi-rater and 360°. Retrieved from http://www.talentsmart.com/products/emotional-intelligence-appraisal-mr.php

Tickle, P. (2006a). The divine hours: A manual for prayer: Prayers for autumn and wintertime (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Image.

Tickle, P. (2006b). The divine hours: A manual for prayer: Prayers for springtime (Vol. 3). New York, NY: Image.

Tickle, P. (2006c). The divine hours: A manual for prayer: Prayers for summertime (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Image.

Tripp, P. D. (2004). Lost in the middle: Midlife and the grace of God. Wapwallopen, PA: Shepherd Press.

Whitney, D. S. (2014). Spiritual disciplines for the Christian life (Revised edition). Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

Willard, D. (1999). The spirit of the disciplines: Understanding how God changes lives. San Francisco, CA: HarperOne.

Rev. Seth J. Nelson, MDiv, is an adjunct instructor in educational ministries and a PhD student in educational studies at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. He recently experienced a midcareer change in his ministerial calling.