A few months ago, in the spring of 2009, the Christian Leadership Center approached me with the request to take over the editorship of the Journal. I accepted this call with some excitement about the possibilities to engage Christian leaders and scholars in a forward-looking dialogue about faith and leadership. If this dialogue is to become a reality both sides of the dialogue must be encouraged to speak. And here is where I discovered a hurdle for the journal that we are still working on in the editorial team.

Let me explain. The first thing I noticed was that during the short years of its existence, the Journal of Applied Christian Leadership has developed a following among Christian leaders in over 100 countries. Many of them are Christian leaders serving Christian communities and a variety of organizations in different capacities. In conversation I discovered that they were looking to the Journal for food for thought that could nourish their hectic and sometimes lonely lives as leaders. They were being asked in these economically turbulent times to do more with less, to aim higher while being stretched thinner, to provide answers to problems not encountered before, and to lead change in a messy environment. To them the neat bundles of scholarly logic and consistency seemed at times out of touch with their world on the edge of chaos. Their lives resembled more a pulse-raising dash across a fast-moving New York street, while the journal seemed to describe a contemplative walk through Central Park where traffic is no more than the humming background noise.

As articles started to come in, I read them in the light of these conversations. It was an eye-opening process. There were several manuscripts that came in, complete with title pages for courses from Christian universities, with little effort to write for a readership other than their professor. Other manuscripts could be classified as empirical research studies containing the statistical analysis sections common in

Erich Baumgartner, JACL Senior Editor, is Professor of Leadership and Intercultural Communication at Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan. good social science research and expertly written with the typical obscure language researchers use to communicate their findings to a select audience of other researchers. I also read Biblical and theological studies that looked at Biblical passages with great detail and sometimes dogmatic persuasion.

But putting myself into the shoes of our readers, I found myself often puzzled. I often lacked the necessary context to understand where the writer was coming from. Occasionally I wished to know how the hero of the study was related to the daily grind of down-to-earth prob- lems. And in the end I was often left with a big question mark: So what? How will the insight of this manuscript inspire, or at least help, Christian leaders to serve better? How can this finding be applied by Christian leaders?

These were not just rhetorical questions. For me they have become the guiding questions to define the mission of the Journal. Leadership is such a complex phenomenon that it defies any simple description or certainty. Servant leadership as a contemporary concept arose out of the cry for leaders who would take seriously the question: Do those served grow as persons? Are their highest priority needs being served with integrity? If we take this question seriously, would it be acceptable to insist that the Journal defines one of its priorities as publishing articles that are readable by leaders of a broad spectrum of organizations, not just theological seminaries, or social science research classrooms? Can a publication like the Journal of Applied Christian Leadership be a peer-reviewed journal with integrity while speaking the language of the leader immersed in the daily dance of leadership life? Can we say it in a way that preserves the precision of careful thought while using words that are common even to those leaders not familiar with the peculiarities of research jargon?

This issue is an attempt to answer this question with a clear “yes.” And I hope you will agree or send us pieces that exemplify that goal. Kevin Wiley’s reflection on “Playing Second Trombone” reminds us that leadership happens even if it is from behind rather than out in front. In fact, executive coach Marshall Goldsmith reminds us that if we forget how much we owe to those second rows of supporting leaders we may just delude ourselves.

Don’t put seniors on the shelf, but realize that they may be a great source of leadership and service, is one of Rhonda Whitney’s insights in her article “Surprised by Joy.” Her findings agree with several national publications that have recently suggested that “not retiring” may be one of the secrets of longevity. On the other side, Miguel Nunez and Sylvia Gonzalez remind us that even Christian leaders may sometimes use their power to set up environments that resemble more the ghettoes of hell rather than cathedrals of grace. Some of our readers may not yet be familiar with the term “mobbing” which is used increasingly to describe abusive behavior in organizations, including Christian organizations, which several countries now prosecute as criminal conduct. This study will help you get acquainted with this problem and spark some ideas of what to do about it.

In each issue we feature a Christian leader that has impacted the world in some remarkable way. If you ever have heard the terms “10/40 window” or “hidden people,” you have encountered the genius of Ralph Winter, one of the most influential mission leaders and strategists of our times who passed away this summer. Russell Staples, a friend and admirer of Ralph Winter, shares with us the astonishing legacy of this servant leader.

Did we achieve a balance between scholarly integrity and insightful application to your world as a Christian leader? You are the judge. I hope that you will let us know. And talk to the leaders of the Christian institutions in your realm of influence who should become subscribing partners in this conversation. You can contact us directly at jacl@andrews.edu, write to the editor, or find some other way as you browse our new website at www.andrews.edu/services/jacl.

GOOD LEADERS MAKING BAD DECISIONS?

Why do good leaders make bad decisions? Brain researchers exploring the errors of judgment which lead to bad decisions point to two unconscious processes the brain relies on to help leaders make decisions efficiently: (1) pattern recognition and (2) emotional tagging. The first process allows the brain to quickly assess what is going on and compare a new situation with patterns we have seen before. Drawing on patterns he or she has seen before, it takes a chess master as little as a few seconds to assess a game and choose a good move. The second process, emotional tagging of the emotional information attached to the memory of an experience or thought tells us whether or not to pay attention to something and what to do about it.

When researchers analyzed why good leaders sometimes make disastrous judgments, they found three “red flag conditions” that induced leaders to see false patterns or be led astray by distorting emotional tags of their memories:

- Inappropriate self-interest that biases us and makes us see what we want to see and ignore important disconfirming

- Distorting attachments to people, things or places that cloud our judgment about a situation or appropriate

- Misleading memories that seem comparable to the present situation but lead us down a wrong

We all have our biases. But when we allow our biases to cloud our decision making, we seriously endanger the organizations we lead. Gary Klein, a psychologist, also found that once our brain leaps to conclusions, we are reluctant to consider alternatives or revisit our initial assessment of the situation. Andrew Campbell, Jo Whitehead, and Sydney Finkelstein, the authors of Think Again: Why Good Leaders Make Bad Decisions (2009), feel that the way the brain works makes it difficult for leaders to spot and safeguard against their own errors in judgment. Thus, instead of relying on the wisdom of single leaders no matter how experienced, they recommend that those involved in important decisions identify possible red flag conditions and bring in appropriate safeguards to introduce more unbiased analysis, open debate and challenge, or stronger governance.

Based on Campbell, A., Whitehead, J., & Finkelstein, S. (2009). Think again: Why good leaders make bad decisions. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

SLEEP DEPRIVATION & TEAM PERFORMANCE

When the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident finished its report, it cited a curious factor that contributed to the collective human error and poor judgment in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster (1986): “sleep loss.” Similarly, the disasters in the nuclear power plants of Chernobyl and Three Mile Island began when it was early morning, “a time when sleep deprivation effects are especially powerful.” All these disasters suggest a relationship between sleep deprivation and team performance. But while the effects of sleep deprivation (SD) on individuals have been documented quite extensively in the literature, it is only recently that researchers have begun to explore how sleep deprivation affects team decisions. In a pioneering article in the

Academy of Management Review,

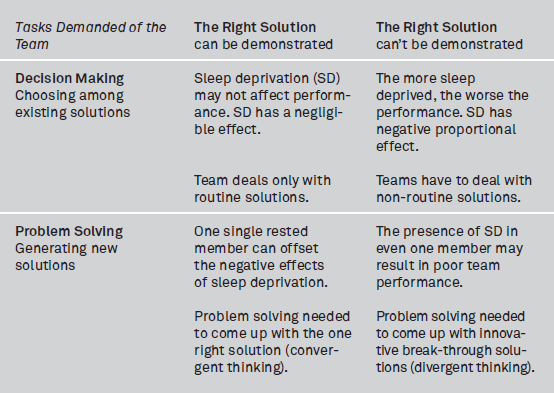

Barnes and Hollenbeck (2009) suggest several effects of SD on team performance (see Exhibit 1):

- Routine tasks may not be affected at all since routine decisions are often based on the automatic nature of information processing which does not draw heavily on the prefrontal cortex. Nonroutine decision making demands the analysis of decision options and will be impacted by SD in a direct negative

- When sleep-deprived teams are faced with the task of coming up with new solutions and innovation, SD can have severe consequences because it affects the pre- cortex structures of the brain necessary for these functions. If the team is just trying to find the one right solution, it can be accomplished by any member of the team able to function and the team will recognize when it has found the right solution. Thus

- Exhibit 1: What Happened to Sleep Deprived Teams?

sleep deprivation can be offset by even a single rested member who shares the right solution with the team. But when sleep-deprived teams are called to come up with innovative solutions to problems with no obvious solution, the team is at a great disadvantage. Even if a member comes up with the right solution there is no guarantee that he or she will be able to convince the rest of the team.

What do all these insights mean for Christian leaders? If critical functions depend on the whole team working in an innovation- generating problem-solving mode, SD may be playing with fire, waiting for an accident to happen.

Source: Barnes, C. M., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (2009). Sleep deprivation and decision-making teams: Burning the midnight oil or playing with fire? The Academy of Management Review, 34(1), 56-66.

EXPRESSING GRATITUDE

Susan and Peter Glaser, in their book Be Quiet, Be Heard: The Paradox of Persuasion (Eugene, OR: Communications Solutions Publishing, 2006, chapter 6), describe gratitude as one of the keys to changing the relational chemistry in an organization and unleashing the power of encouragement. Building on the work of neuroscientists, they observe that the brain typically notices patterns that are out of alignment with expectations.

The Glasers call this ability of the brain the “uh-oh factor” (p. 107). For example: The smell of smoke would most likely send us searching for the source so we can do something about the perceived threat. The problem is that this ability to notice things that are wrong can quickly turn into a climate-setting habit that poisons morale.

Contrary to the typical “praise sandwich” managers use to praise workers first in order to soften the blow of correction, the Glasers suggest that leaders use a more pure praise sandwich:

Step 1: Thank (offer sincere thanks for someone’s effort) Step 2: Offer specifics (mentioning the specific behavior you found helpful and would like to see repeated)

Step 3: Note benefits (indicating how this behavior contributed to some positive outcome for you, the team, the organization)

Step 4: Thank again (ending by reinforcing how grateful you are)

Here is an example: Thank you so much for rearranging your schedule so our committee could meet. This enabled our candidate to meet the deadline and stay on the graduation list. I know that this meant extra work for you. I really appreciate it.

During the holiday season— and throughout the year—you may want to work on your gratitude skills and spread a little thanksgiving to enhance the power of encouragement in your organization.