He will be like a tree firmly planted by streams of water, Which yields its fruit in its season And its leaf does not wither; And in whatever he does, he prospers. Psalm 1:3 (NASB)

An Oak Tree, Landscaping, and Leadership

The Psalms are replete with metaphors that have many layers of meaning. Psalm 1 uses metaphors of a tree, streams, a leaf, fruit, and seasons. Each is rich in meaning. Metaphors are often used to describe important aspects of leadership. Coaching, conducting, and improvising are images from the worlds of sport and music but have been used to offer insight into leadership. There are others. I enjoy landscaping. It too can be a metaphor for leadership.

For many years, my wife and I lived along the Little Elkhart River in Goshen, Indiana. In the backyard we created a landscaped area around an old oak tree. The old tree, estimated to be over 125 years old, was the focal point of the backyard. Around it we developed complementary landscaping, including a little pool and a stream that flowed around the tree and then poured over a flat rock back down to the river nearly twenty feet below. We planted some ornamental trees and created some areas that were closely manicured and others that were more natural. The backyard became a place of rest and contemplation. Landscaping requires creativity and lots of hard work, but it was worth the effort. Recently we sold the house and have relocated.

The backyard at our new home holds new possibilities. I look forward to more experimentation.

Many contemporary writers invite us to consider metaphors as a way to understand leadership. DePree (1989) notes that leadership is as much art as it is science. Wheatley (1999, 2005) asserts that leadership in the turbulent 21st century is about perceiving deep patterns in the midst of chaos and helping others to find a place of belonging and to make a meaningful contribution. Whyte (2001) likens navigating or leading organizational change to “crossing an unknown sea.” Bolman and Deal (2003) specifically address metaphors as they speak of the leader’s work in shaping the symbolic dimensions of organizational reality. Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski, and Flowers (2004) describe some of the deeper reaches of leadership and organizational reality as a capacity to focus “presence.” All of these are metaphors. Each is a little elusive. Their elusive character invites reflection. Each provides a glimpse into the phenomenon of leadership.

In this essay, I recount some of my own journey in leadership development, share some convictions Rick Stiffney, Ph.D., is President/CEO of the Mennonite Health-Services (MHS) Alliance in Goshen, Indiana. about what constitutes effective leadership, and offer a few observations about my ongoing learning as a leader. Landscaping serves as a powerful metaphor for my formation as a leader. Landscaping takes imagination and heavy lifting. But good landscaping begins with a focal point around which other aspects flow.

Truly effective leadership requires imagination and hard work, but it needs a moral center.

A Journey of Service

Since my mid-teens I have served in a variety of leadership roles. Following graduation from Goshen College, I served as a pastor and teacher.

Following this I served nearly a decade in a senior leadership role with a Mennonite denominational mission agency. I served another decade in various senior and executive leadership roles with a large regional aging services provider. I have served in my current role as President and CEO of MHS Alliance for nearly a dozen years. MHS Alliance is a national network of Mennonite-affiliated health and human services organizations. I have been blessed to have opportunities come to me. I was asked to serve in all of these major leadership roles; I did not seek any of them. In a practical as well as theological sense I was “called” to them. At each step, I felt the sometimes subtle and sometimes more overt push of the Spirit of God to move forward to accept the invitation. In most of these assignments, I had major responsibility to dramatically shape or reshape the work of the organization.

In my current work with MHS Alliance, I provide strategic leadership for the organization and staff. The core of my professional work consists of consulting with the leaders and governing boards of our 75 member organizations, as well as with leaders of dozens of other nonprofit organizations from many different religious traditions. In the last twelve months I have worked with organizations rooted in the United Church of Christ, Amish, Quaker, Brethren in Christ, Church of the Brethren, United Methodist, Christian Reformed, Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, Baptist General Conference, and Episcopal Church faith traditions.

At its most basic level, my consulting work is with organizational leaders as they wrestle with issues of call or vocation. At times the work is intensely personal: executive coaching, mentoring, and succession planning. On the other hand, some of my work is with governing boards and senior leaders as they focus on their institutions’ sense of call, mission, identity, strategic direction, and governance. In the personal work, as well as the collective work, my goals are the same—to support their efforts to be effective and stay faithful to their unique sense of mission and call. This kind of work engages boards and senior leaders in what Hester (2000) called “doing theology” (p. 60) and Shea (2000) described as the challenge of integrating spirituality and practicality in leadership (p. 1). This work is fundamentally supporting organizations and their leaders in claiming their faithcenter and beginning to develop culture and strategy around it.

The alignment of my personal sense of call with an opportunity to serve other leaders through MHS Alliance is a special gift. I don’t take it lightly. Alignment between an executive leader’s sense of call and the organization’s mission and deepest-held convictions produces power. This creative power must be used humbly and wisely.

Behold, a [leader] will reign righteously

And [managers] will rule justly.

Each will be like a refuge from the wind

And a shelter from the storm,

Like streams of water in a dry country,

Like the shade of a huge rock in a parched land.

Then the eyes of those who see will not be blinded,

And the ears of those who hear will listen.

The mind of the hasty will discern the truth,

And the tongue of the stammerers will hasten to speak clearly.

(Isaiah 32:1-4, [NASB], with “king” changed to “leader” and “princes” to “managers” in verse 1)

The Focal Point or Moral Center

Like good landscaping, leadership requires a moral center. My Ph.D. work at Andrews University provided an excellent opportunity to reflect on this very matter. Over the last few years, I was often asked why at my age, now nearly 60, I was interested in securing a Ph.D. Some thought I should have been planning for retirement! However, it was a good question. Sometimes I quipped, “Because it was on my bucket list!” While that was true, my interest was far deeper. To be sure, I wanted to increase my knowledge base. But more importantly, I wanted to probe my personal understandings of leadership and sharpen my convictions about effective practice.

My view of leadership begins with a focal point or moral center—my worldview and Christian faith. I was raised in a Christian home. My parents modeled responsible engagement in a local church. Dad was a leader. I became a leader. My commitment to a Christian worldview was further focused and deepened through my young adult years as a student at Goshen College.

I became a committed Mennonite/ Anabaptist. A leader’s worldview or faith informs his moral framework and in turns shapes his practice. Selznick (1957) asserts that a leader shapes the moral character of the organization and in turn its service and place in the larger society. Numerous authors have traced the relationship between the moral fiber or character of leaders and their practice as leaders (Collins, 2001; S. M. R. Covey, 2006; Covrig, 2005; Heifetz, Grashow, & Linsky, 2009; Heifetz, 1994; Kouzes & Posner,

1995, 2003; Palmer, 2000; Shivers-Blackwell, 2006).

Worldview is more than just a fuzzy philosophy. It is more than a set of beliefs about reality. In its richest sense, worldview is about how we view reality and how it shapes the way we live. It is actually quite pragmatic in its impact in our lives. Sire (2004) contends that a fully developed worldview addresses ontology, epistemology, and axiology.

Ontology deals with what we fundamentally believe is true—the nature of reality. Epistemology deals with how we know what is true. Axiology deals with the question of what difference either make in the way we live.

Dilthey and Naugle identified three core convictions fundamental to their worldview: convictions about the nature of reality, belief about the existence of God, and convictions about a purposeful creation (cited in Sire, 2004, pp. 24-27). My worldview embraces these three core affirmations and goes beyond. Faith and worldview are interchangeable.

Following are the core elements of my personal faith:

- God

- God is

- God created and continues to

- Humankind is called to incarnate God’s

- Followers of Christ have an allegiance to a new

- The community of faith is a social reality and is one means through which God’s work can be advanced.

- All human efforts, individually and corporately, fall short of fully expressing God’s love. Even the best of human intentions falls short of the glory of God. All individuals and social organizations are fallen or flawed. All stand in the need of ongoing grace and

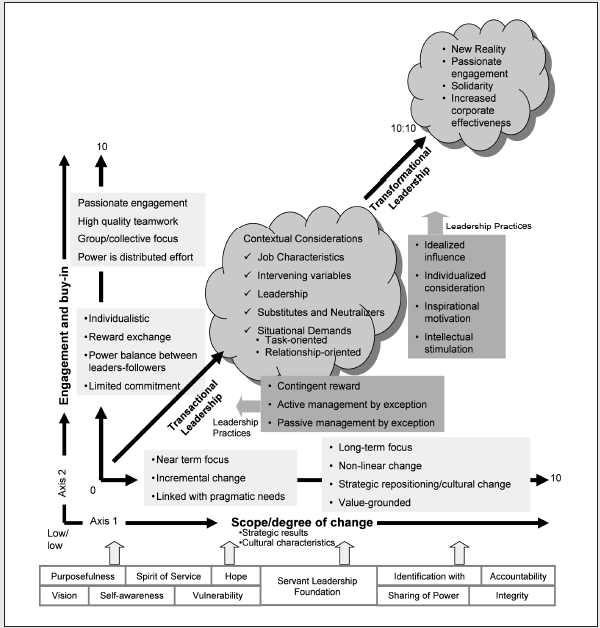

From this centerpiece or focal point, I have been drawn to the fundamental notion of leadership as service—most eloquently framed by Greenleaf (1977) as “servant leadership.” Figure 1 highlights several important additional elements of my leadership framework. This framework links servant leadership, transformational leadership, and contextual or contingency considerations. It reflects the dynamic interplay of these important themes in leadership theory. It represents my personal “landscape” of leadership.

Let me explain the landscape. The framework represented in Figure 1 positions servant leadership as the foundational construct. The chart depicts a continuum of leadership practices from expressions that are essentially short-term, linear, and not substantive in focus (transactional) to practices that are intended to facilitate significant, non-linear, strategic changes in performance or corporate culture (transformational-strategic change). The chart demonstrates that as the scope of change anticipated increases and is more strategic, the time required and the buy-in necessitated increases. Contingency factors or contextual considerations are positioned “in the middle of the fray.” Job characteristics, the lived or felt experience of the follower, are noted as a significant type of contextual consideration. However, it is leadership as service that is critical, regardless of the scope of change or urgency of change needed.

Just as a landscape in nature is never complete, this leadership landscape is never complete. Rather, it is always in process.

Shaping Faith Identity

My dissertation inquiry was an exploration of how a group of CEO’s viewed their role and work in shaping the faith identity of the organizations they serve (Stiffney, 2010). I researched their sense of the landscape. Using a modified case study and collaborative research design, I chronicled the stories of ten CEO’s from across the MHS Alliance. The design engaged the ten CEO’s in telling their story and in discerning some of the key findings. The design reflected the essence of my approach to leadership. I seek to lead in a way that engages others meaningfully in finding solutions and pathways together.

Four core concepts of leadership emerged as foundational: executive role theory, the concept of transformational leadership, leadership as sense-making, and moral agency.

I want to briefly explore the striking and significant ways in which they were represented in the stories.

Executive Role and Embodiment

After studying the work of many man- agers and leaders, Mintzberg (1973) developed a taxonomy of executive leadership that demonstrates that executives spend time working and/or expressing ten different roles.

These might be described as core role expectations. Although the word taxonomy might sound mechanistic or formulaic, Mintzberg viewed effective leadership as dynamic and anything but mechanistic. Although any executive over time expresses the various roles, the degree to which or intensity with which any of these roles are carried out varies based on context. It would be fair to suggest that Minztberg could have characterized an executive’s work as a “dance” between and among many different and important roles.

One of the seminal roles that Minztberg envisioned was that of “embodiment.” This proposition asserts that an executive becomes the embodiment of the organization’s mission, values, and core identity. This is particularly true for a nonprofit organization in which the CEO is the only one person who has responsibility, authority, and accountability for the whole. The CEOs in my research consistently expressed that they view their work as a result of call and that they view their call to serve as congruent with the mission and deepest convictions of the organization. In this very critical sense they see themselves as the embodiment—though flawed— of the organization’s mission and identity.

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership has received substantial attention in the literature of leadership (Bass, 1985;

Figure 1. An Integrated Leadership Framework.

Burns, 1978; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Peters & Waterman, 1982). The core idea is that transformational leadership, in contrast to transactional leadership, focuses on organizational change that is sweeping in scope and strategic in consequence. Such change may be along lines of services, markets, ownership, organizational alignment, identity, and culture.

Most of the CEOs engaged in my research framed their efforts at deepening the faith identity or more fully integrating mission and values in their organizations as requiring transformational leadership.

Sense-making

Sense-making, as promulgated by Weick (1979, 1995) and advanced by many others,( including Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Covrig, 2005;

Eisenberg, 2006; Fairhurst, 2008;

Gioia, 2006; Kouzes & Posner, 2006; Manning, 1997), emphasized the role of leaders in facilitating meaning for constituents within and beyond the organization. This characteristic of leadership was strongly exhibited through the interviews and case studies related to my dissertation exploration of how CEOs understand their role and work in shaping the culture and faith identity of organizations they serve.

Moral Leadership

Finally, Selznick (1957), Covey (2004), Covrig (2005), and Covey (2006) address the fact that leaders bring to their leadership a moral framework. Yanofchick (2008) describes this as a “moral compass.” I believe that conceptualizing leadership as moral agency bridges the theoretical and the practical. Leaders all act ethically in some way. Their behavior is a conscious or unconscious expression of their moral values. Moral frameworks are not all the same. Some moral frameworks support violence; others are life-giving. Thus the resulting leadership ethics also differ. Morals and values shape not only how a leader leads but in what direction she seeks to influence or move others.

My research, experiences with many other leaders, and extensive reading lead me to the following observations about leadership. From my vantage point, these are important features in the landscape of leadership.

- Effective leadership begins with matters of the The character, the moral compass, the “heart” of the leader significantly informs leadership. Leaders have, as Palmer (2000) suggests, the power to bring great light or immense darkness to those that follow. Bolman and Deal (1995,

- 15) point out that the heart of leadership begins with the heart of

- The heart of a servant-leader begins with the intent to serve others. Jesus modeled self-sacrificing, other-focused service. Others have sought to do so. I believe that this spirit of service, its blend of strength and humility, is the only real antidote to dangerous ego-centered

My favorite Biblical text is Philippians 2:5-8:

Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ: Who being in the very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, and being made in human likeness, and being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself and became obedient to death— even death on a cross.

- Faith-affiliated nonprofit organizations can be powerful expressions of the mission of the community of The church or communities of faith have used various organizational forms to advance their mission and witness over centuries. While some of those forms have become oppressive and have given rise to institutions that drifted from the essence of purpose, others have served and served effectively. Faith- affiliated organizations must find an appropriate integration of two themes—faithful expression of core mission and values and marketplace effectiveness. This is a daunting task in the face of very competitive markets, pluralistic constituencies, and relationships within the community of faith that may be ambiguous and ambivalent.

- Leaders and organizations achieve higher levels of integrity as they seek to match their practice to their deepest held convictions or core values. Individual leaders and organizations deal with issues of integrity. Followers respect and follow leaders who are trustworthy and competent (Kouzes & Posner, 1995, 2003). Customers, clients, and other constituents engage with organizations or companies that deliver on their At the end of the day, integrity or ethical congruence is absolutely critical to effectiveness.

- Leaders offer support to organizational constituents as they seek meaning and value through their contribution to the organization’s mission. This approach to leadership is no more true for relationships with internal stakeholders than with external This function is even more important in a 21st-century context in which there is immense turbulence in almost every sector of human experience (Benefiel, 2005; Wheatley, 1999, 2005; Whyte, 1994, 2001).

- Leaders and organizations must seek ongoing renewal. Leaders are human and organizations are human They may be inspired by God and the Spirit of God may infuse every facet, but both leaders and institutions are fraught with the vulnerabilities of human endeavor.

Because humans don’t do everything perfectly, attempts to match practice with principle, and reality with rhetoric, will fall short. Therefore, ongoing personal and organizational renewal is critical. Koontz (1997) addresses squarely this need for renewal when he challenges Christian faith-based organizations to continually seek renewal to more fully express the reign of God.

Like Landscaping, Leadership Is an Ongoing Challenge

Now that I have completed my Ph.D., have I arrived or got it figured out?

No! My understanding about leadership is not static. I have referred to my faith or worldview as the centerpiece or a focal point for my understanding of leadership. It is fundamental—like the old oak tree. But I am now contemplating landscaping in the backyard of our new home.

We need to figure out what will be the primary focal point. From there we will go to the edges of space with imagination, experimentation, and hard work. We learn and adapt as we go. These dynamics are also critically important for leading organizations in the early 21st century.

My notions about leadership are constantly being shaped by learning. Just as in landscaping, I have learned about leadership through experience. I have “practiced” leadership in many different settings. In other words, I learn as I go to the edges. As in landscaping, leading is about going to the edges and learning. I set my observations about leadership and learning in the context of organizations as learning enterprises.

Research and common sense suggest that organizations must remain sensitive to and responsive to their environment. Senge (1990) characterizes organizations that are self-aware and market-savvy as “learning organizations.” Scott (1992) says that organizations that are attentive and responsive to market conditions are naturalistic and open systems. Such responsiveness is critical to survival in the 21st century. Lipshitz, Popper, and Friedman (2002) suggest that organizational learning can and should happen in many interrelated dimensions of the organization. The point is, organizations must be capable of accurately perceiving their operating context, critiquing their current activities, discerning what adaptations are necessary, and shaping effective responses. Organizations must be “other-aware” and “self- aware.” This represents organizational learning at an evolved level.

So too must leaders be other- aware and self-aware. Knight (1989) asserts that all approaches to learning and education reflect underlying presuppositions about ontology, epistemology, and axiology. My faith and worldview infuse my approach to learning and leadership—I begin with them. There is no other place to begin. I am also an existentialist in that I value current experience. I am a constructivist (Gergen, 2006), appropriating the “stuff” of current experience to shape meaning. But these definitions must be nuanced.

My faith affirms the reality of God and God’s active engagement in history and intent for the future. Thus my interpretation of current circumstances is informed by a sense of history and teleology. The life and witness of Jesus Christ is at the center of my sense of history and sense of purposefulness in human experience.

However, I do not live and learn in isolation. Leaders do not lead in isolation. If there are no followers, there are no leaders! I embrace the role of community in knowing and discerning. Freed (2006) asserts that a community of discernment, a learning community, is an important means through which we come to know what is and what ought to be. The Mennonite/Anabaptist faith affirms that the community of believers gathered around the Scripture and guided by the Holy Spirit is a fundamental characteristic of Christian discipleship.

These notions of learning powerfully shape my approach to leadership and service in many different settings. They provoke me to always asking organizations and their leaders, “What can we or should we learn?” They fuel my interest in collaborating with others in cross-cultural settings. I begin all of my work with an assumption that I will have much to learn and perhaps something to offer. This stance of learning results in a spirit of collaboration with others as we together seek to make sense of mission, opportunities, and constraints, and engage in purposeful change. Much of my consulting work offers individuals and groups an opportunity to reflect on their deepest convictions, to assess what is occurring around them, and to shape organizational strategy going forward.

I draw us back to the metaphor of landscaping. It is impossible in landscaping to extend the boundaries without experimentation, observing, trying, and failing. This is all part of the process. Effective servant leadership is about moving from the center out to the edges and back again. In learning theory, Kolb (1984) called this action-reflection learning. It is that—acting, reflecting, re-conceptualizing, and acting again. In the realm of church and missiology, it has been likened unto a ministry of “presence” (Pannabecker, Bender, & Shenk, 1987). Seldom do I get a section of landscaping done right the first time. On occasion I have moved the same boulder many times to get it right!

Leadership is often just like this.

Organizations will not survive in the 21st century without a clear sense of centeredness, mission, and core identity. Faith-based organizations that pay attention only to the marketplace and corporate effectiveness will lose their soul. Similarly, leaders who cannot or do not develop a deep sense of call and core identity as a servant to others will lose their way. As Palmer (2000) so aptly observed, leaders have great capacity to bring either light or deep shadow to those who follow. Being clear about a core sense of call and identity is fundamental to being a source of light, not shadow, in service with others.

Closing Reflections

The governing board to which I report wants to set out some new strategic directions for our national organization. It is not clear what this new season in my leadership work should be about. I conclude this essay with a few personal convictions that I believe will transcend any particular career trajectory to which I might be called. They represent my commitments to further self-awareness and personal growth—becoming a better landscape artist and perhaps a better leader.

- I want to claim as gifts the predispositions I bring to leadership— restlessness, imagination, and a passion for change. These predispositions mean that I naturally am inclined to be a transformational leader—one who is able to facilitate change.

- I want to cultivate the practice of Perhaps it’s a result of being middle-aged. Perhaps it’s the result of seasoning from experience. Regardless, I know that I need to devote more time to reflection and Sabbath. Morning disciplines of quietness and prayer have become habits. Morning is an important time to be grounded in the reality of God’s love, grace, and good providence.

- I want to continue to slow down to engage others. I have been gifted with what others perceive to be an endless supply of It’s not nearly as unlimited as some seem to think. A CEO recently observed that I seem to do everything at 300 miles an hour! Call it drive. Call it frenetic. It’s certainly up-tempo. However, it can easily intimidate. I can be too quick to come to conclusions. I need to slow down—not so I will look right, but because I need the insight of others who engage the process differently. They will engage the process more slowly, more reflectively, and perhaps more wisely. I need that slowing down, and I honor those who lead me to do it!

- I want to continue to learn the joy of delegation and letting Palmer (2000) suggested that often our greatest strengths are also our greatest vulnerabilities. I am slowly learning the joy of letting go and letting others. In general, others do very well—though they may do it differently. In fact, they may do it more creatively and effectively!

- I want to continue to reflect on my role in framing the organizational story and encouraging other executives to do the same. Perhaps among the communication challenges that executives face, this is one of the most important. What is the organization’s story? How can it be framed in ways that are honest, winsome, and accessible? My dissertation research evidences that if organizations are to develop and sustain strong core identities in a faith tradition, they need CEOs who understand and prize the distinctive convictions of that tradition (Stiffney, 2010).

- I want to choose integrity in all my work and communication. While this may seem self evident, it’s worth mentioning. I am a high “I” and high “D” on the DiSC inventory. I am an ENTJ on the Myers-Briggs I am a green/blue combination on the Birkman Leadership Inventory. I score lowest in modeling the way on the Kouzes/Posner Leadership Practices Inventory. All this is to say that I can be a driver and a consummate politician.

Politicians can be attractive—even effective. They can also be deceitful. I know I am prone to exaggeration (at least so says my wife). I can also be overly optimistic in the most trying of circumstances. In a Harvard Business

Review article, Maccoby (2000) speaks of the significant contributions of positive narcissism. Therefore, I need to attend to being straightforward, transparent, truthful, and vulnerable.

- I believe I am entering a season of life with significant opportunities to mentor young leaders and gov- erning boards. Whether in my current role or not, I will be about this work.

Finally, in this next season I want to engage more meaningfully with my family and the local community of faith. A demanding professional career and a Ph.D. program have forced me to scrimp on family and congregational commitments. I intend to engage more deeply. These commitments are absolutely critical to staying real, finding support, and being a loving person in this world.

They may in fact help me be a more effective leader. I have much to learn. Leadership, like life and landscaping, is a work in progress.

References

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Benefiel, M. (2005). Soul at work: Spiritual leadership in organizations (Vol. 1). New York: Seabury.

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1995). Leading with soul: An uncommon

journey of spirit. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2003). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leader- ship. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Collins, J. (2001). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap and others don’t. New York: Harper Collins.

Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006).

Transformational leadership and job characteristics: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 327-340. doi:10.2307/20159766

Covey, S. (2004). The 8th habit: From effeciveness to greatness. New York: Free Press.

Covey, S. M. R. (2006). The speed of trust: The one thing that changes everything. New York: Free Press.

Covrig, D. M. (2000). The organizational context of moral dilemmas: The role of moral leadership in administration in making and breaking dilemmas. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 7(1), 40-59.

doi: 10.1177/107179190000700105

De Pree, M. (1989). Leadership is an art. New York: Doubleday.

Eisenberg, E. M. (2006). Karl Weick and the aesthetics of contingency. Organization Studies, 27(11), 1693-1707. doi: 10.1177/0170840606068348

Fairhurst, G. T. (2008). Discursive leadership: A communication alternative to leadership psychology. Management Communication Quarterly, 21(4), 510-521. doi: 10.1177/0893318907313714

Freed, S. (2006). A conceptual framework for knowing: 5 ways of knowing. Retrieved January 30, 2006, from http://d21.andrews.edu./d2l/tools/ LMS/styles /style1/nva.asp?ou= 26388&topicId=167682&h

Gergen, K. (2006). Constructivist epistemology.

Retrieved January 1, 2006, from http:www.cdli.ca/-elmurphy/ emurphy/cle2.html

Gioia, D. A. (2006). On Weick: An appreciation. Organization Studies, 27(11), 1709-1721.

doi: 10.1177/0170840606068349

Greenleaf, R. (1977). Servant leadership:

A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist.

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009, July-August). Leadership in a permanent crisis. Harvard Business Review, 87(7-8), 62-69.

Heifetz, R. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge, MA: Belnap Press of Harvard University Press.

Hester, D. (2000). Practicing governance in the light of faith. In T. Holland & D. Hester (Eds.), Building effective boards for religious organizations: A handbook for trustees, presidents, and church leaders. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Knight, G. R. (1989). Philosophy and education: An introduction in Christian perspective (2nd ed.). Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Koontz, T. (1997). Church-related institutions. Mennonite Quarterly Review, LXXI(3), 421- 438.

Kouzes, J., & Posner, B. (1995). The leadership challenge. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kouzes, J., & Posner, B. (2003). Leadership credibility: How leaders gain it, lose it, and why people demand it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kouzes, J., & Posner, B. (2006). A leader’s lega- cy. San Francisco: Wiley.

Lipshitz, R., Popper, M., & Friedman, V. J. (2002). A multifacet model of organizational learning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 38(1),79-98. doi: 10.1177/0021886302381005

Maccoby, M. (2000). Narcissistic leaders: The incredible pros, the inevitable cons.

Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 69-77.

Manning, P. K. (1997). Organizations as sense- making contexts. Theory,

Culture & Society, 14(2), 139-150. doi: 10.1177/026327697014002012

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The nature of managerial work. New York: Harper & Row.

Palmer, P. (2000). Let your life speak: Listening for the voice of vocation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pannabecker, S. F., Bender, H. S., & Shenk, W.

- (1987). Mission (Missiology). Retrieved from http://www.gameo.org/ encyclopedia/contents/M575.html

Peters, T., & Waterman, R. H. (1982). In search of excellence: Lessons from America’s best- run companies. New York: Harper & Row.

Scott, R. W. (1992). Organizations: Rational, natural, and open systems (3rd ed.).

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in administration. New York: Harper & Row.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline:

The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency.

Senge, P., Scharmer, C. O., Jaworski, J.,

& Flowers, B. (2004). Presence: An exploration of profound change in

people, organizations, and society.

New York: Doubleday.

Shea, J. (2000). Challenges and competencies.

Health Progress, 81(1), 1-6.

Shivers-Blackwell. (2006). The influence of perceptions of organizational structure and culture on leadership role requirements: The moderating impact of locus of control and self-monitoring. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 12(4), 27-49. doi:10.1177/107179190601200403

Sire, J. W. (2004). Naming the elephant: Worldview as concept (Vol. 1). Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Stiffney, R. (2010). The self-perception of executives concerning their role and work in shaping the faith identity of nonprofit Mennonite/Anabaptist organizations: A collaborative case study and narrative approach.. Doctoral dissertation, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI.

Weick, K. E. (1979). The social psychology of organizing (2nd ed.). New York: Random House.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sense-making in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wheatley, M. (1999). Leadership and the new science: Discovering order in a chaotic world. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Wheatley, M. (2005). Finding our way: Leadership for an uncertain time. San Francisco: Berrett and Koehler.

Whyte, D. (1994). The heart aroused. New York: Currency Doubleday.

Whyte, D. (2001). Crossing the unknown sea: Work as a pilgrimage of identity. New York: Riverhead

Yanofchick, B. (2008). Leadership formation: Choosing between the compass and the checklist. Health Progress, 89(1), 20-25.