Abstract: For nearly two millennia, Jews and Christians have struggled to interact with each other and engage in meaningful dialogue. The tragedy of the Shoah only deepened and enlarged the chasm that exists between these two faith groups. How can this fracture be healed, and reconciliation or even dialogue emerge? This article explores the work of The Matzevah Foundation in its efforts to create a nexus within the liminality of a Jewish cemetery in which Jews and Christians may mutually interact and cooperate as they care for and restore Jewish cemeteries in Poland. By examining acts of loving-kindness, Jews’ and Christians’ attitudes are influenced, creating mutual bridges of understanding. This study suggests a framework and a potential model for Jewish and Christian dialogue and highlights critical aspects of the experience of dialogue.

Keywords: Jews and Christians; interfaith relationships; dialogue; reconciliation; Jewish cemeteries

Introduction

In June 2004, I had an unexpected conversation with a waitress in a hotel restaurant that would change my life forever and lead me in a different direction. I was working with a company of American young people in a Baptist church in Otwock, Poland, a suburb of Warsaw. Anna, the waitress, was curious about us and our work. She asked me many questions and was pleased with the good that we were doing for her community.

One morning as Anna and I were talking, she surprisingly suggested that I take this group of young people to visit the nearby Jewish cemetery. Anna was a Polish woman of Jewish descent; I was a Baptist pastor. What did Anna’s suggestion mean? What should I do? Ultimately, her suggestion led me to ask myself, “What should be the Christian response to the Shoah?”

In 2005, I began a journey to answer this question, which led me to care for and restore Jewish cemeteries in Poland. My purpose was to open a pathway to Poland’s Jewish community that could lead to dialogue and reconciliation. In 2010, to continue the work I began in Poland, a group of Christian friends and I established a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation, The Matzevah Foundation (TMF). I conducted a case study of the work of TMF and its efforts to bring Jew and Christian together by safekeeping the Polish-Jewish cemeteries.

Through the inquiry of Jews’ and Christians’ interactions in this liminal space of the Polish-Jewish cemetery, I sought to understand how acts of loving-kindness influence attitudes and create mutual bridges of understanding as to the underpinning for dialogue. My investigation asked two primary questions. First, how have Jews and Christians responded to the work of TMF? Second, in what ways did Jews and Christians learn how to dialogue within their interaction in the work of TMF?

I discovered that Jews and Christians reacted to the work of TMF in five ways: developing relationships, engaging in loving acts, remembering, restoring, and reconciling. These reactions produced the foothold of dialogue. The data revealed a framework for dialogue that emerged from Jewish and Christian interaction comprised of seven components: addressing proselytism, developing the common ground, increasing understanding, building a sense of community, speaking about matters of faith, confronting the present past, and overcoming differences them.

My study discovered a potential model for Jewish and Christian dialogue and contributed a greater understanding of the experience of dialogue. Instead of meeting and talking, the distinctive difference of dialogue, as encountered in this study is the creation of a nexus within the liminality of a cemetery. Here, Jews and Christians may mutually interact and cooperate in the restoration of Jewish cemeteries in Poland.

The Choice

Do we wander across the face of this earth aimlessly, without purpose? Are we sovereign monarchs who circumnavigate the terrain of our lives because, as Henley (1893) suggests, we are the masters of our fates and the captains of our souls (p. 57)? Or, does the One who created us and loves us, the Almighty Himself, order our steps and direct our paths? If the Lord of Hosts knows the number of hairs on our heads and leads us into green pastures, then how do we recognize His leadership? What then do we do, and how do we respond when we realize that the Great Shepherd wants to lead us in a different direction? Like sheep at a new gate, do we balk, or do we yield to His leadership and enter the unknown?

I faced such a choice in June 2004.

I was a Baptist minister, serving in Poland. One day, I had an unexpected conversation with a waitress that would forever change my life and lead me in a completely different direction. I met Anna in the hotel restaurant, where I stayed with a group of young American volunteers. These volunteers assisted me with a small Polish-Baptist congregation in Otwock, a community just outside of Warsaw. Anna was a waitress who served us daily. She did not speak English; nonetheless, she was interested in us and our work. At every meal, Anna asked me many questions about who we were and what we were doing. I explained to her in Polish that we were working with a local group of Baptists to serve her community by teaching English, conducting a day camp, and sharing Bible stories. Anna was delighted with the good that we were doing for her city.

One morning, as Anna and I talked, and she surprisingly suggested that I take a group of young people to visit the nearby Jewish cemetery. Up to that point, I had lived in Poland with my family for seven years. I spoke Polish well, had read Poland’s history and had a good understanding of Polish culture. I realized that Anna’s suggestion was uncharacteristic for typical Polish interest. It was an unusual topic to broach with me, someone whom she did not know well. Discussing such Jewish matters were commonly avoided and considered to be taboo in many cultural settings in Poland.

By suggesting that I visit this Jewish cemetery, Anna took an enormous risk and crossed into a terrain divided by longstanding racial and religious tensions, disputed memories of WWII, and filled with trauma and strife. She was inviting me to enter a contested cultural space, a third space, which exists sandwiched between Jewish and Catholic Poles, i.e., between Jews and Christians. How should I respond? I knew that I had to choose my words carefully. I did not ask her if she was a Jew or if she was Jewish, as this type of question would be a faux pas—a cultural blunder. Instead, I asked her politely: “Czy ma Pani pochodzenie zydowskie (Madam, are you of Jewish descent)?”

She replied, “Yes.” And then quietly added, “There are many of us in hiding here.”

At that moment, I felt the weight and power of Anna’s words. Equally, I realized that what she was saying to me was particularly precious. A Polish woman of Jewish origin was suggesting to me, a minister of Christ, that I visit a Jewish cemetery. It was as if she was inviting me to see it. Regardless, I did not understand what her proposal meant, or why she would make such a suggestion to me. Despite my uncertainty, I sensed that God led me to visit this cemetery; nonetheless, I did not know why. What would I see? Why did it matter? What was so significant about a cemetery to a Jew, or someone like Anna, who had Polish-Jewish heritage? Why should a Jewish cemetery matter to me as a Christian, and most significantly, as a Baptist minister? What did God wish for me to do?

If you were in my shoes, what would you do?

My Response

For me, the answer was simple. I wanted to find out why a Jewish cemetery in Poland was so significant to someone like Anna and, more broadly, Polish Jews. I felt compelled by God to learn more by researching and exploring this matter, pondering these uncertain questions, and visiting this Jewish cemetery.

Before I could visit the Jewish cemetery in Otwock, I researched Jewish cemeteries and their importance in Poland. I discovered that Jewish cemeteries were one of the physical remnants of the Jewish presence in Poland—a visible testimony to the once vast, pre-WWII Jewish community that had lived in Poland for nearly a thousand years. Poland had had the largest pre-war Jewish population of any country in Europe before the Nazis decimated roughly ninety percent of them. These Jewish cemeteries were powerful testimonies of the physical and cultural genocide perpetrated by the Third Reich. Furthermore, the Nazis burned numerous synagogues and houses of prayer; they desecrated almost all Jewish cemeteries by destroying or removing the stone matzevot (Hebrew plural form for headstones) and used them as building materials.

My search for understanding led me to this question: “What should be the Christian response to the Shoah?” During the Shoah, also called the Holocaust, six million European Jews were exterminated by the Nazi regime. The Shoah occurred in an overwhelmingly Christian Europe, where ninety percent of the population was Christian. Jews were a distinct minority and a convenient target of hatred. More than half of the Jews exterminated during the Shoah, nearly 3.5 million, were Polish Jews who lost their lives in the German death camps of occupied Poland. What remained, what spoke most strongly of their presence in Poland, were the roughly 1,200 to 1,500 abandoned Jewish cemeteries scattered across Poland. These cemeteries had virtually no one to care for them. To a Jew, caring for the dead, including cemeteries, is one of the highest commandments to perform according to the Halakhah (i.e., Jewish law).

During the summer of 2004, along with some friends, I visited the Jewish cemetery just outside of Otwock. I was amazed by what I saw. It was almost invisible, hidden among the trees, lying situated in a forest, overgrown and neglected. On the faces of the matzevot, I discovered Jewish iconographies, such as the Star of David, the Levitical vase, and the hands of the kohanim (temple priests). Tragically, I also found throughout the cemetery broken and damaged matzevot. Additionally, I found apparent vandalism in its midst, as some matzevot had been sprayed painted with anti-Semitic graffiti. What should I do now that I had seen the Jewish cemetery to which Anna had directed me?

The Path to Dialogue and Reconciliation

As I considered this question, a radical idea emerged. What if I cared for this one neglected Jewish cemetery in Anna’s town? Would it make any difference? Would it matter? What would it take to do it, and what would it look like? Caring for this Jewish cemetery could be a means by which I might, as a Christian, speak to the injustice of the Shoah and open a dialogue toward reconciliation with the Polish-Jewish community. What would it look like if I led Baptist volunteers from the US to work with Polish Christians in attentive care for this small Jewish cemetery hidden away in the forest just outside Otwock?

To undertake such a task, I first had to open a dialogue with the Warsaw Jewish community. In March 2005, I met with the Chief Rabbi of Poland’s representative on the Rabbinical Council for Matters of Cemeteries. I asked this representative if it would be possible to bring Baptist volunteers to care for the Jewish cemetery in Otwock. He asked me, “Why would you want to do such a thing?”

I simply replied, “Reconciliation.”

With that one word, I began my quest for reconciliation, leading me and others from one matzevah (Hebrew singular for headstone) to the next.

Ultimately, it led a group of Christian friends and me to establish The Matzevah Foundation (TMF) in December 2010 as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation registered in Georgia and determined by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to be a public charity.

I had established TMF with a group of friends. Now what? We would continue the work that I began in Poland in caring for and restoring Jewish cemeteries. Although I had been leading Jewish cemetery restoration projects in Poland for many years, I felt something was missing. There was yet something that I needed to learn, but what? I wanted to address the dilemma we faced, as a group of Christians leading TMF, concerning how to care for and restore Jewish cemeteries as Christians.

To answer this question, TMF had to grow in its understanding of what it means to be Jewish and address the aftermath of the Shoah today and its direct impact on Jewish-Christian relations. For this reason, I had to learn. Subsequently, in 2011, I entered the Leadership Program of Andrews University to pursue a PhD, so I might develop TMF as an organization while deepening our understanding of what it means to be Jewish and speak to the injustice of the Shoah.

The Matzevah Foundation

TMF is a small nonprofit organization operated by a board of directors consisting of seven people and a small volunteer staff. TMF exists to educate the public about the Shoah, commemorate forgotten mass grave sites of Jewish victims of the Shoah, and care for and restore Poland’s Jewish cemeteries. TMF conducts its mission in cooperation with numerous Jewish descendants, Jewish and non-Jewish organizations, universities, churches, local governments, civic associations, schools, and communities who wish to speak to the injustice of the Shoah by preserving the Jewish heritage of Poland.

For the past eight years, in its 30-plus Jewish cemetery restoration projects, TMF has engaged over 1,300 volunteers, of whom roughly seventy-five percent are local, while the remaining volunteers are from the United States, Canada, Israel, Australia, Argentina, South Africa, and Europe. These volunteers gather and collaborate in Jewish cemetery restoration projects conducted each summer in cities and communities across Poland where Jewish communities once thrived.

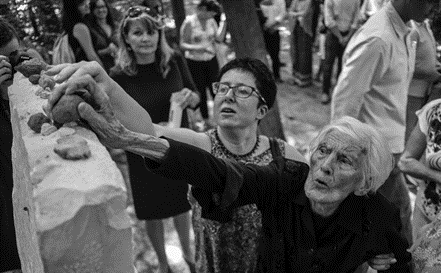

In each project, participants are involved in an intensive week of labor in which they experience first-hand the loss of the Shoah by cleaning or removing debris, cutting brush and undergrowth, and restoring some aspect of the Jewish cemetery that was desecrated during and after WWII. Volunteers spend free time together: going for coffee, having casual conversations, or interacting with each other in structured environments where tough issues are explored. During the week, educational and cultural excursions are planned so that volunteers may learn more about the history and people of the region or locality.

A Research Project

To carry out its mission, TMF cooperates with community and government leaders in Poland. Also, it has developed collaborative partnerships with Jewish and secular institutions in the United States and Europe. These diverse groups of people are interconnected through the work of TMF through safeguarding and rebuilding neglected Jewish cemeteries in Poland. As a part of my learning journey, I first wanted to analyze how Jews and Christians responded to TMF and its work. Second, I wanted to explore how Jews and Christians learned to dialogue within the construct of the third space—the liminal space of the Jewish cemetery in Poland.

Therefore, to study the matters, I conducted a case study of TMF and its work. As a qualitative researcher, my role in this project was direct. The part I played was more in line with that of being a participant and observer. The purpose of my investigation was to describe the process of how acts of lovingkindness (mercy), encountered through the work of TMF, in caring for and restoring Jewish cemeteries in Poland, have influenced dialogue (or lack thereof) among Jews and Christians. My research explored mercy as the language of dialogue, and TMF illustrated that dialogue. In my study, I understood mercy in terms of “loving acts” (Johnson, 2012, p. 127), which I corroborated by humane orientation, concern for others, compassion, charity, and altruism.

Contemporary Jewish-Christian Relations

In 1933, Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, leading Nazi Germany toward war and the Shoah’s historical cataclysm. Many people consider that anti-Semitism was based on the Third Reich’s decision to implement the Final Solution to the Jewish Question in Poland. However, this is not the case. The Nazis strategically adopted Poland as a surrogate for “their gigantic laborato- ry for mass murder,” solely because Poland was the home to the most significant European Jewish population (Zimmerman, 2003, p. 3).

Following “the Erschütterung, ‘shock’ of Auschwitz” (Fackenheim, 2002, para. 8), it is apparent that something within the framework of Christian theology and social consciousness needed to change. Nothing substantially altered in the Christian outlook. Many Christians “attempted to pick up and continue as though no rupture had occurred, and no transformation was required” (Karpen, 2002, p. 139). Krajewski (2005) declares, “Christian-Jewish dialogue nowhere began before World War II” (p. 207). The profound terrors of the Shoah, and the “break in history” it produced, justifiably led some Jews and Christians to realize their need for dialogue.

Concomitantly, Krajewski specifies that “the shock of the Shoah” coupled with “the establishment of the state of Israel led to a deeper dialogue in the West;” however, he maintains that “in Poland, the shock [of the Shoah] was almost non-existent, and certainly not expressed” (p. 207). Krajewski reasons that this inimitable reality in post-war Poland is understandable and is perhaps because of the acuteness of “general Polish suffering” (p. 207), as well as the proximity “of the death camps [making] reflection harder” (p. 208). Furthermore, he posits that Christian-Jewish dialogue in Poland did not emerge until after the Nostra Aetate statement and the communist forced emigration of Jews in 1968 and 1969; only then did the “Polish-Catholic intellectuals began the work of establishing the early stages of dialogue” (p. 209).

In 1947, a group of Christians and Jews met formally in Seelisberg, Switzerland. They wanted to mutually declare their collective anguish about the Shoah, their wish to confront anti-Semitism, and “their desire to foster stronger relationships between Jews and Christians” (International Council of Christians and Jews, 2009, p. 2).

In more recent times, Karpen (2002) states that Jewish-Christian dialogue “has become commonplace” (p. 4); however, it is still challenging. Moreover, he suggests that the events of the Shoah are “exercising a powerful transforming effect not only upon Judaism but also upon Christianity” (p. 205). Broad swaths of “the Christian Church have begun a process of abandoning the teaching of contempt” and have discarded anti-Judaistic theological teachings (p. 205). Kress (2012) views Jewish-Christian interaction as primarily improving because Christians have re-evaluated their “attitude toward Jews and Judaism” (para. 1). Despite these efforts, Christians and Jews remain divided and struggle to interact.

Investigating Jewish-Christian Relations in the Third Space

Because of long-standing religious, racial, and cultural tensions, a complex and challenging relationship exists between Jews and Christians. The resulting breach isolates and separates these two faith groups from each other. They struggle to interact and engage in meaningful dialogue, repairing the breach, and leading to forgiveness and reconciliation. Dialogue can provide a bridge over the gap between Jew and Christian, allowing them to meet in the third space—the transformative space of the Jewish cemetery in Poland. Jews and Christians may deal with the evil of the past through what academic researchers term as loving acts.

To explore how Jews and Christians involved in or affected by the work of TMF and how they have developed in their relationship with one another, I investigated two questions:

- How have Jews and Christians responded to the work of The Matzevah Foundation?

- In what ways do Jews and Christians learn how to dialogue through their mutual interaction within the context of the work of The Matzevah Foundation?

How I Conducted My Study

I utilized a case study method to conduct my study of TMF, as an investigative approach seemed to be the best manner to investigate the work of TMF. Through such an inquiry, I sought to understand how Jews and Christians responded to the work of TMF and in what ways they learned how to dialogue within the framework of the third space (i.e., the Jewish cemetery in Poland). I wanted to determine whether acts of loving-kindness influenced attitudes and created mutual understanding bridges, which might serve as the underpinning for dialogue.

I principally examined the individual and corporate responses to a series of open-ended questions about their experience in working with TMF in its educational initiatives and its Jewish cemetery restoration projects in Poland. I selected specific participants (and locations) primarily for this study using the criterion of Patton (2002): whether participants are “information-rich” (p.237); I specifically selected participants who had knowledge of, and experience in, working with TMF in the United States or Poland. I prepared seven fundamental and open-ended interview questions to conduct individual and focus group interviews.

I selected participants in this study from a pool of 15 individuals, as demonstrated in Table 1, who have interacted with the work of TMF. Of the 15 individuals selected for the study, 11 individuals have had a direct association and have cooperated with me, or in some capacity of my leadership of TMF. Four individuals were selected from two summer project locations in Poland and were interviewed along with four other TMF volunteers and board members in two focus groups. Six participants were Jewish, while six were Christians; the remaining three participants were non-Jewish and primarily non-religious.

Table 1

Demographic Composition of Research Sample

| Frequency | Percentages | |

| Age Group | ||

| 20–35 | 7 | 46.7 |

| 36–45 | 3 | 20.0 |

| 46+ | 5 | 33.3 |

| Total | 15 | 100.0 |

| Educational Level | ||

| Bachelors | 7 | 46.7 |

| Masters/Doctorate | 8 | 853.3 |

| Total | 15 | 100.0 |

| Religious Identity | ||

| Jewish | 6 | 40.0 |

| Christian | 6 | 40.0 |

| Not Stated | 3 | 20.0 |

| Total | 15 | 100.0 |

| Nationality | ||

| American | 10 | 66.7 |

| Polish | 2 | 13.3 |

| United Kingdom | 3 | 20.0 |

| Total | 15 | 100.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 6 | 40.0 |

| Female | 9 | 60.0 |

| Total | 15 | 100 |

Significant Background Material

A Talmudic Leadership Principle

Embedded within the Talmud, we discover an essential leadership principle: “One who causes others to perform [me’aseh] a meritorious act is greater than one who performs that act himself” (Bava Batra 9a, 2017). First, me’aseh or ma’aseh means “the work” (Ma’aseh, 2019), or doing the work, while second, a “meritorious act” is known as a mitzvah (mitzvot, plural)—a righteous act fulfilling one of the 613 commandments of Jewish Law (Halakhah).

The kernel of truth found within this Talmudic principle is that the one who leads or “causes others” (Bava Batra 9a, 2017) to do the work of the mitzvah is superior to the one who merely does the mitzvah. Consider this concept, Jacobs (n.d.) points out that individuals “can do much” in tackling the surrounding needs; she concludes, “We can be even more effective when we mobilize others to join us in these efforts” (para. 22). Hughes, Ginnett, and Curphy (2012) echo this conclusion and assert that leadership is “the process of influencing an organized group toward accomplishing its goals” (p. 5). For this study, leadership, therefore, may be mostly understood as accomplishing work through others.

Combining leadership concepts from Fiedler’s work in 1981 and Hollander’s contributions in 1978, Hughes et al. (2012) consider leadership a cooperative effort. They argue that leadership is a give-and-take process, ongoing in the relationship between a leader and followers, in which the leader influences the group in realizing its goals within the construct of an “interactional framework,” comprising “three elements—the leader, the follower, and the situation” (p. 15).

The Values of Micah 6:8

Researchers and authors (e.g., Melé & Sánchez-Runde, 2013; Purpel, 2008; Stenger, 2006; Wolf, 2010a) show a standard, moral framework for humanity that serves as a basis to interact with our neighbors in the communities in which we live. Wolf (2010b) indicates that Malloch “argues that historically, the spiritual capital of Protestant business persons focuses on the three virtues of faith, hope, and charity” (p. 8). According to Wolf (2010b), Malloch maintains that a “Jesus-shaped worshipview [sic] . . . yields a worldview triad of leadership discipline (faith), social compassion (charity), and persevering justice (hope)” (p. 8).

Consequently, I may connect Malloch’s “three virtues of faith, hope, and charity” to a moral template or pattern consisting of justice, mercy, and humility. Although some would question the source of these values, these three moral values, as seen in Micah 6:8, are transcendent and universal, being, in themselves, a moral standard.

The prophet Micah wrote, “He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God” (ESV, 2016). Hyman (2005) states that the rabbis determined that Micah 6:8 “by virtue of its three principles of doing justice, loving mercy, and walking humbly with God,” captured the essence of the 613 commandments in the Halakhah (p. 157). Additionally, Hyman (2005) suggests that the core of Micah 6:8 is based on a tripartite pattern of a simple string of three verbs emphasizing “doing, loving, and walking—connected to three basic moral values—justice, mercy, and humility,” which “make it comprehensible and easy to remember” (p. 164).

Telushkin (2006) asserts that the prophet Micah teaches us “God’s primary demand of human beings is to act righteously [or justly]” (p. 14). Telushkin (2006) expounds, saying that God does not require from us sacrifices or religious rituals; “rather, God’s most significant demands are justice, compassion, and humility” (p. 14).

The Torah teaches that justice is focused upon our actions toward others. On the authority of Telushkin (2001), the Hebrew word tzedakah is translated as justice or righteousness, and “is usually translated, somewhat inaccurately, as charity” (p. 573). He elaborates further by stating that acting justly “is perhaps the most important obligation Judaism imposes on the Jew” (p. 573). By extension, justice means that we are to be fair in how we deal with other people. We are not to lie, cheat, or steal. If people seek justice, they help others, the oppressed, and care for orphans and widows. These actions express mercy.

In Micah 6:8, the concept of mercy originated from the Hebrew word chesed, which means treating others with kindness, or more accurately with loving-kindness. Mercy may also be expressed as chesed shel eme, literally “kindness of truth” or true loving-kindness (Sienna, 2006, p. 79).

Mercy is also an action—gemilut chasadim—which is the giving of lovingkindness. This type of kindness shows concern or care for others; furthermore, we understand this kindness as compassion. When considering the burial of the dead gemilut chasadim, or acts of loving-kindness, it is viewed as “par excellence because it necessarily is done without any hope that the ‘recipient’ will repay the good deed” (Telushkin, 1994, p. 25). Telushkin (1994) indicates that a rabbi, Haffetz Hayyim, considered gemilut chasadim as “any good deed that one does for another without getting something in return (Ahavat Chesed)” (p. 25). The Talmud considers compassion to be “the hallmark of an ethical person,” and it “is the defining characteristic of being a Jew” (Telushkin, 2006, p. 20).

A Concern for Humanity

Deeds of loving-kindness lay the bridge of mercy. By mobilizing Jews and Christians to engage in this mitzvah, they may come to terms with the past trauma brought about by long-term anti-Semitism, anti-Judaism, and the Shoah through the utilization of “loving acts” (Johnson, 2012, p. 127). Johnson (2012) considers that “Scott Peck is not alone in arguing that loving acts can overcome evil” (p. 127). Peck (2012) defines love in this manner: “Love is as love does. Love is an act of will—namely, both an intention and an action. Will also implies choice” (p. 83, loc. 1078). Therefore, loving acts are actions that flow out of love or concern for others. The concept of loving acts may be academically linked to humane orientation.

Humane orientation may be defined as “the degree to which individuals in organizations or societies encourage and reward individuals for being fair, altruistic, friendly, generous, caring, and kind to others” (Javidan & Dastmalchian, 2009). Kabaskal and Bodur (2004) explain further that “this dimension is manifested in the way people treat one another and in the social programs institutionalized within each society” (p. 569). Simply stated, humane orientation is concerned with the welfare of humanity.

Descriptions of humane behavior are not new but have existed since antiquity, and “ideas and values” related to this dimension may be found among “classic Greek philosophers” and “in the teachings of many of the major religions of the world” (Kabaskal & Bodur, 2004, p. 565). The principal idea embedded in the classical Greek understanding concerning this human attribute is reciprocal and mutual love found in friendship. Humans are interrelated and connected; therefore, love or concern for others is a fundamental expression of humanity.

The Ethics of Remembering

Karpen (2002) offers three critical theoretical insights into how Christians might conceptually respond to the Shoah. First, he argues for the need for “an ethic of remembering” (p. 205). Second, he maintains that there needs to be “a way to place memory [of the Shoah] closer to the heart of Christianity” (p.205). Third, through inference, he provides a glimpse into how to remember and bring the memory of the Shoah “closer to the heart of Christianity” by working “together on the task of tikkun olam, the repair of the world” (p. 206).

Karpen’s three postulations provide a seedbed to root my theory, which I am exploring to bridge the chasm and close the gap between Jews and Christians. Briefly, I may reorder Karpen’s concepts and express them in this way: remembering, repairing the world and bringing the memory closer to Christians by working together with Jews. In this manner, Karpen’s concepts may be linked to the work of TMF, which is guided by three analogous principles: remembering, restoring, and reconciling.

Understanding Dialogue

Dialogue may be a confusing and unclear term. It is more than a conversation, and it is undoubtedly more than a discussion. However, it is not a debate. According to Isaacs (1999), dialogue is not a discussion and is not centered on “making a decision” by ruling out options, which leads to “closure and completion” (p. 45). The root connotation of decision means to “murder the alternative” (Isaacs, 1999, p. 45). Dialogue does not rule out options. As claimed by Isaacs (1999), dialogue means “a shared inquiry, a way of thinking and reflecting together” (p. 9). Dialogue seeks to discover new options, which provide insight, and a means by which to reorder knowledge, “particularly the taken-for-granted assumptions that people bring to the table” (Isaacs, 1999, p. 45).

Dialogue in the context of this study means “a shared inquiry, a way of thinking and reflecting together” (Isaacs, 1999, p. 9). In this light, Isaacs views dialogue as existing in terms of a relationship with someone else. He contends that dialogue is not about our “effort to make [that person] understand us;” it is about people coming “to a greater understanding about [themselves] and each other” (Isaacs, 1999, p. 9). Shady and Larson (2010) point to Buber’s work in dialogue, which advocates for “a shared reality where all partners in the dialogue come to understand each other’s position, even if they do not entirely agree with it” (p. 83).

The vital aspect of dialogue is seeing new outcomes and an opening of a way to pursue them. Dialogue may be linked with liminal space and create the possibility of changing the status quo or the way things are in Jewish and Christian interaction.

Foremost Discoveries in the Study

My first research question for this study asked, “How have Jews and Christians responded to the work of The Matzevah Foundation?” From the interviews, observations, and other data, I discovered that Jews and Christians reacted to the work of TMF by responding in five significant ways. First, they responded by developing relationships as they cooperated in the work of TMF. Second, in terms of loving acts, they cared for Jewish cemeteries in Poland. Third, Jews and Christians remembered the Shoah and linked remembering with action to preserve the memory of Poland’s Jewish past. Fourth, Jews and Christians engaged in tikkun olam as they worked with each other to repair the world of forgotten Jewish resting places in Poland. Fifth, in practical terms, Jews and Christians experienced reconciliation by working together to care for Jewish cemeteries in Poland.

My second research question asked, “In what ways do Jews and Christians learn how to dialogue through their mutual interaction within the context of the work of The Matzevah Foundation?” The data revealed a framework for dialogue emerging from Jewish and Christian interactions within the context of TMF. The TMF structure of Jewish-Christian dialogue consists of seven components: addressing proselytism, developing common ground, gaining understanding, building a sense of community, speaking about matters of faith, confronting the present past, and overcoming differences. The findings also reveal the experience of dialogue within the realm of TMF’s work and discovered a potential model for Jewish and Christian dialogue.

What Do these Discoveries Mean?

First, in the discussion of what I discovered, I will consider the critical aspects of the results as they relate to the five distinct ways in which Jews and Christians responded to the work of TMF. Except for reconciliation, I will pair and discuss the following discoveries as couplets: relationships and caring, and remembering and restoration. Second, I will discuss how Jews and Christians learned to dialogue within the framework of TMF. Finally, in my treatment of the findings, I will examine how the outcomes might be applied to real-life circumstances that leaders may face in their respective leadership fields.

Relationships and Caring

Jews and Christians first responded to the work of TMF by building and developing relationships through caring, loving, or compassionate acts. Kessler (2013) defines dialogue in terms of a relationship and states, “dialogue begins with the individual, not with the community” (p. 53). In light of my study, this means that if relationships are defined by interpersonal interaction, then relationships are a crucial factor in determining if genuine dialogue is possible among Jews and Christians interacting within the construct of TMF. Resolving conflict between groups is not achieved in a vacuum or without effort.

For example, Participant 1 considered the work of TMF with the Jewish community as “bridge-building.” He stated, “What you are doing is building a bridge to the Jews. You have no guidebook, no example to follow, but you keep at it, learning as you go.” He declared, “We Jews should meet you halfway.” Participant 1 also considered the bridge-building efforts of TMF to develop “inter-religious relation[ships].” He shared that building bridges and relationships are “something that we can build together, something [with which] we can inspire each other.” Flannery (1997) contends that Christians need to “adopt the Jewish agenda” and take a step toward reconciliation (p. 3). Christian leaders, or any leader involved in conflicted situations, must initiate the process of reconciliation by attempting to span the chasm between themselves and the person or group(s) with whom they have conflict. Building bridges leads to bridging differences and removing barriers among opposed parties, such as in my case: Jews and Christians.

Karpen (2002) infers a linkage between memory, caring, and restoration. He states that the Shoah’s memory needs to be placed “closer to the heart of Christianity” (p. 205). I may conclude that the Christian heart should care about Jews impacted by the Shoah and demonstrate their concern concretely in some manner. Karpen (2002) argues that if Christians could understand the Shoah, they could work together with Jews “on the task of tikkun olam, the repair of the world” (p. 206). What is crucial in his statement is the hint he provides, allowing me to theoretically connect the Shoah to Christian’s hearts by bringing Jews and Christians together to repair Jewish cemeteries in Poland. My findings support such a notion.

Whether religious or not, leaders wishing to deal with conflict, strife, or injustice in their communities should care and act in such a manner to express their concern. Leaders should have compassion for the needs around them and be concerned about the suffering, oppression, and marginalization of people within their communities. Academically, we understand a compassionate response to need as humane orientation. Humane orientation “is the degree to which individuals in organizations or societies encourage and reward individuals for being fair, altruistic, friendly, generous, caring, and kind to others” (Javidan & Dastmalchian, 2009).

Participant 2 illustrated such compassion. She stated, “If you care for somebody, you’re going to act. If you love somebody, you’re going to act,” because, as she reasoned, a person cannot love another person “from a distance and not have interaction.” In the same way, she asserted, “You can’t care for something, or someone, and not have interaction with them.” Peck (2012) hypothesizes that love is more than a feeling or emotion; he considers love as “an act of will—namely, both an intention and an action” (p. 83, loc. 1078).

Since relationships are dynamic exchanges among people, they grow and develop. In building relationships, people may change how they understand and view each other gradually in the context of their interaction. Participant 3 reflected upon the impact of our relationship on her. Since we first met, she shared, “[I have] grown as a person as a result of knowing you, and to me, that’s part of friendships.” She emphasized how she has changed by stating,“You didn’t ask me outright, but the relationship asked me to open my ears differently, open my mind, open my way of seeing things.”

Participant 3’s comments indicate the development of trust, along with describing elements of the experience of dialogue and transformational learning. Her comments point toward the process of reconciliation. Edward Taylor (2007) emphasizes one of the “essential factors” found in a “transformative experience” is based upon building relationships with other people who trust each other (p. 179); transformational learning is not abstract but a rather concrete and mutual experience. It is through these “trustful relationships” that people can engage in dialogue, discuss and share information freely, which allows them to “achieve mutual consensual understanding” (p. 179).

Remembering and Restoration

Recalling the Shoah, Participant 2 declared, “I think of the wrongness that was done. I think of evil.” Participant 4 remarked, “One of the great tragedies about the Holocaust,” was the instantaneous, almost complete halting of memory, and, “I think that was part of the purpose of what transpired during the Holocaust, to totally erase” the memory of Jews. The Nazis were committing both physical and cultural genocide. Participant 3 mirrored this understanding and considered “what the Nazis had done.” She said, “[They were] not just destroying the communities and Jewish life, but they were trying to erase the fact that there was Jewish life by destroying the cemeteries.” Given such injustice, humanity cries out for justice—for the wrong to be made right.

Participant 5 asserted, “To desecrate graves of people who are no longer there to defend themselves in any way,” is an injustice and “absolutely despicable, the lowest thing you can do.” Participant 5 believes the work of TMF creates an opportunity for people to act socially and provides for them “the chance to do something” for the community, which she considers as “doing what is right.” Participant 6 viewed his motivation to be involved in the work of TMF as “seeking justice for those who can’t seek it for themselves.”

Remembering and caring for Jewish cemeteries may be linked conceptually with restorative procedures that change the physical state of Jewish cemeteries and transform those caring for them. In basic terms, restoration is “the act of restoring to a former state or position . . . or to an unimpaired or perfect condition,” while restoring means “to bring back to the original state . . . or to a healthy or vigorous state” (Bradshaw, 1997, p. 8). Herman (2015) asserts that remembering allows for “the restoration of the social order,” and it enables individual victims to experience healing (p. 1).

Karpen (2002) defines reconciliation as “to restore [a relationship] to friendship or harmony” (p. 3). Wilkens and Sanford (2009) consider that redemption contains within it “the basic idea of restoration” (p. 196). Restoration is not merely about restoring or redeeming physical spaces or their status within a particular community; it is more so about restoring and redeeming broken relationships between people.

In particular, Participant 7 affirmed that through pursuing justice, Jews and Christians “can come together for an action that expresses both of our faiths.” He concluded, “That action is to repair these cemeteries that are falling apart, that are neglected, and to do God’s work together in bringing a sense of justice and wholeness and peace to our world.” His comments reflect the underlying Jewish understanding of restoration, which is encapsulated by tikkun olam.

In Judaism, the concept of tikkun olam is a Hebrew term meaning “repair of the world” (Sucharov, 2011, p. 172). Tikkun olam historically has been understood in terms of restoring, restorative works, or healing; in contemporary times, it “has come to connote an ethical outlook by which we strive to create a better world” (Sucharov, 2011, p. 174). Also, such restorative work or repair is viewed as “a process that extends beyond the bounds of the dyadic field to include the surrounding world context” (Sucharov, 2011, p. 175). According to Pinder-Ashenden (2011), “The concept of tikkun olam surely resonates strongly with devastated souls yearning for healing and redemption” (p. 134). The work of restoration involves repairing the broken world around us. Restoration is a process, not a product.

Participant 3 contended that since TMF invests its time, money, and effort “into doing the work . . . it says that you are committed to this healing process.” Moreover, she stated, “You’re not just espousing ideas of, ‘Oh, let’s kumbaya,’ and the world is going to get back together again. You’re actually doing something on the ground, which I think is a lot more meaningful.”

The essential aspect of restoration is the linking of Jew and Christian in the physical space of a Jewish cemetery, allowing substantial interaction. Participant 8 illustrated the interplay of physical and social restoration, which occurs in a Polish-Jewish cemetery by proclaiming, “The mutual hope is that our work brings full healing between Christian and Jew, and on an even more particular plane between Christian Poles and Jews.”

Leaders should understand that their local community’s history is not something static, sitting isolated on an island in the past. Events of the past influence the fabric of society today and will continue to reverberate into the future unless leaders act to restore the social order. Memory is not passive. It is active. As leaders remember an injustice or some social need in their community, they should take steps to speak to whatever the injustice or wrongdoing was and seek to redeem the community’s situation. Altruism and benevolence are actions that demonstrate concern and a commitment, along with a willingness to invest time, money, and effort within their community to see the status quo change.

Reconciliation

In simple terms, Jews and Christians experienced reconciliation by working together as they cared for and restored Jewish cemeteries in Poland. Karpen (2002) defines reconciliation as meaning “not only ‘to restore to harmony’ but also, in the mathematical sense, ‘to account for’” (p. 9). Volf (2000) considers reconciliation to have more than a theological meaning, which most Christian theologians understand as the “reconciliation of the individual and God” (p. 162). He maintains that justice should be understood “as a dimension of the pursuit of reconciliation, whose ultimate goal is a community of love” (p. 163). Also, he reasons that reconciliation has a vertical dimension (between God and humanity) and a horizontal dimension (among men and women) and concludes that without this “horizontal dimension reconciliation would simply not exist” (p. 166).

For this case study, I considered reconciliation’s essential meaning to be reconnecting and bringing together disjointed elements by gathering Jews and Christians to care for and restore Jewish cemeteries in Poland. This study’s data indicates that reconciliation embraces the transformation of perspectives across a broad array of viewpoints, ranging from religious to secular, from Jew to Christian, from board member to volunteer, and from those with long-term or first-time interaction with the work of TMF.

Learning, according to Kolb (2015), may be defined as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (p. 49). Taylor (2007) emphasizes one of the “essential factors” found in a “transformative experience” is based upon building relationships with other people who trust each other (p. 179). By giving Jews “an opportunity” to be a part of Jewish cemetery restoration projects, Participant 3 maintained that TMF provides the Jewish community “a chance to learn the lessons that I did . . . otherwise, they’re not going to get it.” She contended that if Jews “just go to the death camps,” it would only reinforce “our victimization.” She continued, “I think that we thrive on the victimization, and we’d like to think that we’re always the victims.”

Thus, Participant 3 was convinced that TMF Jewish cemetery restoration project offers “an opportunity for people [Jews] to grow, change, and rethink their preconceptions about Christians, Poles in Poland.” Concluding, she stated, “I suppose, and obviously, if there can be better understanding and a sharing of values and see that there are Christians who share our values, that [scenario] could have life.”

Participant 2 realized from her experiences with TMF and her interaction with Polish and Jewish people, she has developed “new views” and has had “new opportunities” and experiences “to process,” which she otherwise would not have. She affirmed, “So, with each experience in life, something is going to change, good or bad, or just everyday experiences change you to some degree.” By having conversations during “the work that we do in Poland,” she said, “[it] will change you, if you let it—and, if you are willing to be immersed in it, and not just be a bystander.”

When TMF engages local Polish communities in its work in a Jewish cemetery, Participant 9 postulated that, “it causes the young people to ask questions. It causes the older people to dig up memories.” He shared if local Poles take part physically in restoring a Jewish cemetery, it “allows them also to start . . . changing their perception, opening their eyes, their perception of the history, the reality of the place.” In effect, Participant 9 thinks the work of TMF becomes a mediator of change and allows people to consider their viewpoints and change their understanding of the Jewish space in their communities.

Participant 9 theorized that TMF also functions as a “disinterested third party” in the Polish and Jewish communities’ interaction. Participant 9 linked his understanding of how TMF functions to Levinas’ theory of the third party. As stated by Corvellec (2005), the third party may be understood as “the other of the other, who stands in front of me” (p. 18). Garcia (2012) states, “It’s wrong to interpret his [Levinas] philosophy as if there are only two people” (para. 7) who are interacting with each other. According to Garcia, Levinas distinguishes “between the closed society of two people,” who stand opposite of each other, “and the open society, who are open to all see” (para. 7). The relationship between two people is not a closed system, but it is open to multiple others, who are viewed as the third party. Corvellec (2005) declares, “The third party disturbs the intimacy of my relationship with the other and provokes me to question my place in the world and my responsibility toward society” (p. 18).

Dialogue

As an American Jew, Participant 3 has experienced the rift between Jews and Christians as “separateness.” Bridging this gap, or closing the fissure between Jews and Christians, is not easily accomplished; as a group of Christians, who established TMF, we desire to heal the wounds and close the breach through the work of TMF. Therefore, dialogue is a crucial aspect of our work and one of the primary foci of this study. Do the findings show that Jews and Christians are learning to dialogue, or are they even dialoguing at all?

According to Isaacs (1999), dialogue is not a discussion, and it is not centered on “making a decision” by ruling out options that lead to “closure and completion” (p. 45). Isaacs proposes that dialogue seeks to discover new outcomes and possibilities, which provide insight and a means by which to reorder knowledge, “particularly the taken-for-granted assumptions that people bring to the table” (p. 45). Likewise, Isaacs views dialogue as “a shared inquiry, a way of thinking and reflecting together” (p. 9). Subsequently, he regards dialogue as occurring in terms of a relationship with someone else. He contends that dialogue is not about our “effort to make [that person] understand us;” it is about people coming “to a greater understanding about [themselves] and each other” (p. 9).

What makes dialogue really work? Kessler (2013) indicates that “dialogue begins with the individual, not with the community” (p. 53). Donskis (2013) emphasizes that dialogue requires not only the capacity to hear and listen but a willingness to set aside personal presumptions and “to examine one’s own life” (para. 5). Dialogue is an interchange framed by humility and not by arrogance or pride. In dialogue, parties should not seek to “prevail over [their] opponent at whatever cost” (Donskis, 2013, para. 5). As Donskis (2013) infers, if dialogue is approached in humility, it will “arrest our aggressive and agonistic wish to prevail, and dominate at the expense of someone else’s dignity, not to mention the truth itself” (para. 5).

What is needed for genuine dialogue to occur? Theoretically, dialogue should be possible among Jews and Christians as an interchange between people. Dialogue should be probable during the interaction of Jews and Christians while working with each other in caring for Jewish cemeteries in Poland. Therefore, as we have seen thus far in my discussion of the findings, Jews and Christians respond to the work of TMF by developing relationships, engaging in loving acts, remembering, restoring, and reconciling.

The findings from this study show that of these five core responses, the work of TMF facilitates dialogue in at least four ways. First, as discussed previously, developing relationships is a crucial factor in dialogue. Second, loving or compassionate acts serve as a means to bridge the chasm between Jew and Christians and allow them to stand together by caring for Jewish cemeteries in Poland. Third, through remembering and restorative acts, or tikkun olam, Jews and Christians may experience reconciliation by mutually cooperating in managing and restoring Jewish cemeteries in Poland. Fourth, it is in the context of the Jewish cemeteries of Poland, where relationships are built, compassion is expressed, and remembering, recovering, and reconciling occurs. Jews and Christians find themselves in an emerging space, a third space in which dialogue is possible. Each person who enters this unknown territory must decide what they leave behind and embrace the discovery of something uniquely new.

Pinto (1996) advances the notion that there is a “Jewish space inside each European nation with a significant history of Jewish life” (p. 6). Gruber (2017) reasons that Pintos’s concept delineates “the place occupied by Jews, Jewish culture, and Jewish memory” inside the framework of the European social order, “regardless of the size or activity of the local Jewish population” (loc. 7887). Gruber also considers that such Jewish space may be “‘real imaginary’ spaces: spaces, be they physical and/or within the realm of thought or idea that are, so to speak, both ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ at the same time” (loc. 7872).

Researchers refer to this so-called “Jewish space” as liminal space, and the concept is denoted as liminality, which was “created by Arnold Van Gennep (1909) and Victor Turner (1959)” (Auton-Cuff & Gruenhage, 2014, p. 2). Franks and Meteyard (2007) maintain that liminality is “the state of being betwixt and between where the old world has been left behind, but we have not yet arrived at what is to come” (p. 215).

Rohr (2003) posits that the only escape for a person entrapped in “normalcy, the way things are,” is to enter a “sacred space,” termed liminality (from the Latin limen) (p. 155). Rohr reasons that in liminal space, it is possible to encounter “all transformation” by moving “out of ‘business as usual’” and leave behind the “old world, . . . but we’re not sure of the new one yet” (p.155). Thus, liminality allows Jews and Christians to encounter “a genuine hearing of the Other” (Kessler, 2013, p. 53), move beyond the status quo, and experience the reality of dialogue.

In terms of the work of TMF, what are the essential elements of dialogue? The findings point to seven critical components of dialogue in the context of TMF. These elements are: (a) addressing proselytism, (b) developing common ground, (c) gaining understanding, (d) building a sense of community, (e) speaking about matters of faith, (f) confronting the present past, and (g) overcoming differences.

- Addressing proselytism: Christians must address proselytism if they wish to pursue dialogue with Jews. For this discussion, proselytism is a problematic term and is not easily defined. According to Bickley (2015) customarily, “the word . . . meant the attempt to persuade someone to change their religion;” however, he claims contemporary interpretations of the meaning of proselytism have “come to imply improperly forcing, bribing, or taking advantage of vulnerabilities in the effort to recruit new religious adherents” (p. 9). Proselytism is not merely the methodology of religious conversion. Broadly understood, proselytism means persuading people to change their beliefs, viewpoints, or brand loyalties.

- Finding common ground: Participant 6 alluded to common ground and finding it is crucial for dialogue. Participant 2 explained that “the relationships that we [TMF] have are just as important as the work that we do in the cemetery.” Likewise, she clarified her views about her interactions with Jews in this third space—a Jewish cemetery—by describing a discussion that she had on one occasion with Participant 1. She shared, “[Our interaction] was because of our relationship through [the work of TMF].” She believes that “there is no other reason on earth that he would have been with us . . . had it not been for [TMF].” In reflecting, she said, “If it had just been [with] my church, or group of my friends from America coming over to work in Poland, there would be no reason for him to be there.”

- Gaining understanding: Participant 3 is a good example of gaining understanding. She reflected upon how she has gained understanding throughout our dialogue; she stated, “So, based on our interaction . . . you have helped me understand . . . well, certainly the majority of [Christianity in] this country, or Christianity anyway [as] the basis of this country.” Likewise, she has learned that we share “more in common than differences.” In conclusion, she stated, “I feel like you come from a purity of heart, and that’s what connects with me. So, the cultural differences are already there, but what I’ve learned is that the values are the same, and that helps us connect.”

- Building a sense of community: Not every Jewish cemetery restoration project that TMF facilitates in Poland is the same. Each one is unique. One goal Participant 8 and I established for the Jewish cemetery restoration project in Markuszów was to bring these two diverse groups of people together, and from the outset, build a sense of community. Besides living, eating, and working together throughout a week that was tough and complicated, we added group activities that would bring the group together. For example, we planned excursions for the group, such as being tourists, visiting the concentration and death camp of Majdanek, and daily debriefings following each workday.

- Speaking about matters of faith: In racial interactions, Singleton and Hays (2008) advise participants engaged in group discussions to “speak [their] truth” and point out that “a courageous conversation requires that participants be honest about their thoughts, feelings, and opinions” (p. 21). The notion of speaking truth intersects well with a Jewish concept termed Dabru Emet, which means “speak the truth to one another” (Steinfels, 2000, para. 2).

Tippett (2007) states, “Religion never ceased to matter for most people in most cultures around the world. Only northern Europe and North America became less overtly religious in the course of the twentieth century” (loc. 203). Religious matters cannot be entirely avoided when people interact. Irrespective of faith, cultural traditions, or lack thereof, matters of belief will express themselves in dialogue across the spectrum of religious groups. Although vitally important, TMF is not seeking to advance inter-faith dialogue; when Christians and Jews interact with each other within the framework of a Jewish cemetery restoration project in Poland, matters of faith arise in their conversations from time to time. - Confronting the present past: In caring for and restoring Jewish cemeteries in Poland, the work of TMF hinges upon acting in the present while responding to the devastating impact of past tragedies regarding the Shoah. It cannot be assumed that Jewish descendants, local Poles, volunteers, or anyone involved in the work of TMF do not have personal thoughts and feelings about the tragic events and the aftermath of the Shoah.

- Overcoming differences: Participant 1 considered what we have accomplished over the past decade in our interaction as Jew and Christian in working together in mass graves and in Jewish cemeteries. He stated, “I feel that you are reaching where few want to reach. You drilled yourself through a thick wall, and you are on the other side. You are inside of that environment that is traumatic, and this is what I mean by getting deeper [in our relationship].”

Overcoming differences, navigating obstacles, and “drilling through a thick wall” of separateness is building a bridge to span the separation between Jews and Christians. Moreover, he said, “You need huge persistence and patience because people are different, and sometimes they divide. They try to evaluate, who is better, and who is worse.” He acknowledged that in my work, I have experienced such a pattern “from both sides—Baptist, [and] Jewish.” Still, despite these difficulties, Participant 1 shared, “You believe in that friendship. You believe we can overcome these walls.”

The Jewish cemetery in Poland is a liminal space, a third space, a nexus that allows Jews and Christians to interact with each other in the concrete act of restoration. The Jewish cemetery is a means to an end. The end I seek is dialogue and reconciliation. Leaders need to understand that, in what I have discovered, reconciliation is a process and not a product. To reconcile means to bring together and unite fragmented people. Dialogue explores new possibilities and opens pathways that challenge the existing status quo of communities in conflict. Therefore, dialogue and reconciliation may occur within a defined intermediary space in which people in conflict may join in a compassionate and beneficial activity for their community.

Leaders should pause and ask themselves these types of questions: Does my community struggle with a past injustice? How does this injustice influence the interaction of people within my community? Does conflict surround this situation, or is there community discord or strife because of it? What is the space, or pathway, present within the landscape of the community that would allow people to interact, dialogue, and work with each other toward resolving the conflict that will make a difference in their community? Answering such questions will enable leaders to open pathways and work toward dialogue and reconciliation.

Conclusion

The consistency of the data from this case study, as well as the interaction of Jews and Christians within its framework, strongly leads to the conclusion that this study contributes to the larger body of research regarding dialogue. It contributes explicitly to Jewish-Christian relations and provides valuable data concerning Jewish-Christian dialogue. Beyond the findings presented in the discussion thus far, several conclusions are indicated.

- Jews and Christians must address the historical rift that separates them and deal with the effects of the Shoah. Relationships between Jews and Christians are not naturally occurring; therefore, they must be consciously established and built. Thus, someone must become a peacemaker and reach out to the other, attempting to develop a relationship between them. Relationships are a crucial aspect of genuine dialogue, and the third space of the Jewish cemetery in Poland provides validity for Jews and Christians to interact.

Christians must acknowledge past prejudices and unjust acts. The Christian heart must be concerned about how the Shoah affects Jews today. Jews must be willing to acknowledge Christian efforts to deal with past injustices and close the rift between them. For Christians, working in Jewish cemeteries in Poland with Jews is a way to place the memory of the Shoah closer to their hearts. Likewise, for Jews, restoring a Polish-Jewish cemetery with Christians would allow them to acknowledge Christian efforts and enable them to inter- act with Christians. - The work of TMF creates a liminal space in the Polish-Jewish cemetery that establishes a nexus between Jews and Christians. Jews and Christians are transformed through their relationships and their interactions within the third space framework, or the Jewish cemetery in Poland. Remembering leads to compassionate or loving acts that seek justice for those who have no voice and cannot “seek it for themselves.” Remembering and caring for Jewish cemeteries may be linked conceptually with restorative actions that change the physical state of Jewish cemeteries and transform communities and the interaction of Jews and Christians. Restoring, restorative acts, or tikkun olam—the repairing of the world—is a process, not a product. The essential aspect of restoration is the linking of Jew and Christian in the physical space of a Jewish cemetery, allowing them to interact substantially with each other.

Dialogue is predicated upon interpersonal relationships between Jews and Christians within the liminal space of the Jewish cemetery in Poland. It is within this context that relationships are built, compassion is expressed, and remembering, restoring, and reconciling occur. Jews and Christians find them- selves in an emerging space, a third space in which dialogue is possible. Each person who enters this unknown territory must decide what they leave behind and embrace the discovery of something uniquely new and unexpected. - TMF builds relational bridges that lead to bridging differences and removing barriers among Jews and Christians. Loving acts, or compassionate acts, serve to bridge the chasm between Jews and Christians, allowing them to stand together by caring for Jewish cemeteries in Poland. Jews and Christians may experience reconciliation by mutually cooperating in caring for and restoring Jewish cemeteries in Poland. The reconciliation process embraces the transformation of perspectives across a broad array of viewpoints among Jews, non-Jews, and Christians. TMF functions as a third party, a catalyst, and a mediator, enabling Jews and Christians to interact, facilitating dialogue, healing, and the process of reconciliation.

References

Auton-Cuff, F., & Gruenhage, J. (2014, July). Stories of persistence: The liminal journey of first generation university graduates. Paper presented at the Higher Education Close Up 7, Research Making a Difference, Lancaster University, Lancashire, UK.

Bava Batra 9a. (2017). In The William Davidson edition of the Koren Talmud Bavli Noé Edition (A. E. I. Steinsaltz, Trans.). Retrieved from Sefaria.org

Bickley, P. (2015). Problem of proselytism. London, UK: Theos.

Bradshaw, A. D. (1997). What do we mean by restoration? In K. M. Urbanska, N. R. Webb, & P. J. Edwards (Eds.), Restoration ecology and sustainable development (pp. 8–14). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Corvellec, H. (2005). An endless responsibility for justice: For a Levinasian approach to managerial ethics. Levinas, Business Ethics, 9.

Donskis, L. (2013). The art of difficult dialogue. New Eastern Europe, 6. Retrieved from http://neweasterneurope.eu/2016/09/21/the-art-of-difficult-dialogue/

Fackenheim, E. L. (2002). Faith in God and man after Auschwitz: Theological implications. Retrieved from http://www.holocaust-trc.org/faith-in-god-and-man-after-auschwitz-theological-implications/

Flannery, E. H. (1997). Jewish-Christian relations: Focus on the future. Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 34, 322–325. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=509669029&site=ehost-live

Franks, A., & Meteyard, J. (2007). Liminality: The transforming grace of in-between places. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling: JPCC, 61(3), 215–222. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=17958086&site=ehost-live

Garcia, L. (2012, February 21). Third party. Leo and Levinas Walk into a Bar. Retrieved from https://leoandlevinaswalkintoabar.wordpress.com/2012/02/21/third-party/

Gruber, R. E. (2017). Real imaginary spaces and places: Virtual, actual, and otherwise. In S. Lässig & M. Rürup (Eds.), Space and spatiality in modern German-Jewish history (Kindle ed.). New York, NY: Berghahn.

Henley, W. E. (1893). Out of the night that covers me. In A book of verses (Fourth ed.). New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Herman, J. L. (2015). Introduction. In Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence, from domestic abuse to political terror (Kindle ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Holy Bible. (2016). English Standard Version. Retrieved from https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Micah+6%3A8&version=ESV

Hughes, R. L., Ginnett, R. C., & Curphy, G. J. (2012). Leadership: Enhancing the lessons of experience. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Hyman, R. T. (2005). Questions and response in Micah 6:6–8. Jewish Bible Quarterly, 33(3), 157–165. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=17479659&site=ehost-live

International Council of Christians and Jews. (2009). A time for recommitment: Building the new relationship between Jews and Christians. Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations, 4(1), 1–22. Retrieved from http://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/scjr/

Isaacs, W. (1999). Dialogue and the art of thinking together: A pioneering approach to communicating in business and in life (1st ed.). New York, NY: Currency.

Jacobs, J. (n.d.). Fighting poverty in Judaism. Jewish thought. Retrieved from https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/fighting-poverty-in-judaism/

Javidan, M., & Dastmalchian, A. (2009). Managerial implications of the GLOBE project: A study of 62 societies. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 47(1), 41–58. doi:10.1177/1038411108099289

Johnson, C. E. (2012). Meeting the ethical challenges of leadership: Casting light or shadow. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Kabaskal, H., & Bodur, M. (2004). Humane orientation in societies, organizations and leader attributes. In R. J. House (Ed.), Culture, leadership and organzations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 564–601). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Karpen, J. F. (2002). Remembering the future: Towards an ethic of reconciliation for Jewish and Christian communities (Publication No. 3048893) [Doctoral dissertation, Union Theological Seminary, ). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Kessler, E. (2013). “I am Joseph, your brother:” A Jewish-perspective on ChristianJewish relations since Nostra Aetate No. 4. Theological Studies, 74(1), 48–72. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=85783170&site=ehost-live

Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NH: Pearson Education Ltd.

Krajewski, S. (2005). Poland and the Jews: Reflections of a Polish Polish Jew. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Austeria.

Kress, M. (2012). Jewish-Christian relations today. Jew and non-Jews. Retrieved from http://www.myjewishlearning.com/history/Jewish_World_Today/Jews_and_Non-Jews/Jewish-Christians_Relations.shtml

Ma‘aseh. (2019). Englishman’s concordance. Retrieved from https://biblehub.com/hebrew/maaseh_4639.htm

Melé, D., & Sánchez-Runde, C. (2013). Cultural diversity and universal ethics in a global world. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(4), 681–687. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1814-z

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Peck, M. S. (2012). Love defined. In The road less traveled: A new psychology of love, traditional values and spiritual growth (Kindle ed.).

Pinder-Ashenden, E. (2011). How Jewish thinkers come to terms with the Holocaust and why it matters for this generation: A selected survey and comment. European Journal of Theology, 20(2), 131–138. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=67358187&site=ehost-live

Pinto, D. (1996). A new Jewish identity for post-1989 Europe. Institute for Jewish Policy Research, 1(June 1996), 1–15. Retrieved from https://archive.jpr.org.uk/download?id=1442

Purpel, D. E. (2008). What matters. Journal of Education & Christian Belief, 12(2), 115–28.

Rohr, R. (2003). Return to the sacred. In Everything belongs: The gift of contemplative prayer (Kindle ed.). New York, NY: The Crossroad Publishing Company.

Shady, S. L. H., & Larson, M. (2010). Tolerance, empathy, or inclusion? Insights from Martin Buber. Educational Theory, 60(1), 81–96. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5446.2010.00347.x

Sienna, B. (2006). Acts of lovingkindness bring Torah into the world. Kolel–Haftarot 5766. Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/document/7384520/Kolel-Haftarot-5766

Singleton, G. E., & Hays, C. (2008). Beginning courageous conversations about race. In M. Pollock (Ed.), Everyday antiracism: Getting real about race in school (pp. 18–23). New York, NY: New Press.

Steinfels, P. (2000). Beliefs; Ten carefully worded paragraphs encourage Jews to consider a thoughtful response to changes in the relationship between Christianity and Judaism. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2000/09/23/us/beliefs-ten-carefully-worded-paragraphs-encourage-jews-consider-thoughtful.html

Stenger, V. J. (2006). Do our values come from God? The evidence says no. Free Inquiry, 26(5), 42–45. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=21797187&site=ehost-live

Sucharov, M. (2011). A Jewish voice and the creation of a tikkun olam culture-discussion of irreducible cultural contexts: German-Jewish experience, identity, and trauma in a bilingual analysis. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology, 6(2), 172–177. doi:10.1080/15551024.2011.552412

Taylor, E. W. (2007). An update of transformative learning theory: A critical review of the empirical research (1999–2005). International Journal of Lifelong Education, 26(2), 173–191.

Telushkin, J. (1994). Jewish wisdom: Ethical, spiritual and historical lessons from the great works and thinkers. New York, NY: William Morrow & Company, Inc.

Telushkin, J. (2001). Jewish literacy: The most important things to know about the Jewish religion, its people and its history (Revised ed.). New York, NY: William Morrow & Company, Inc.

Telushkin, J. (2006). A Jewish code of ethics: You shall be holy (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Bell Tower.

Tippett, K. (2007). Speaking of faith: Why religion matters–and how to talk about it (Kindle ed.). New York, NY: Penguin Publishing Group.

Volf, M. (2000). The social meaning of reconciliation. Interpretation, 54(2), 158–172. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rfh&AN=ATLA0000912219&site=ehost-live

Wilkens, S., & Sanford, M. L. (2009). Hidden worldviews: Eight cultural stories that shape our lives. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic.

Wolf, T. (2010a). Lifecode: An examination of the shape, the nature, and the usage of the oikoscode, a replicative nonformal learning pattern of ethical education for leadership and community groups (Publication No. 1555) [Doctoral Dissertation, Andrews University]. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1555/

Wolf, T. (2010b). Social change and development: A research template. New Delhi, India: University Institute.

Zimmerman, J. D. (2003). Introduction: Changing perceptions in the histography of Polish-Jewish relations during the Second World War. In J. D. Zimmerman (Ed.), Contested memories: Poles and Jews during the Holocaust and its aftermath. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Steven D. Reece, PhD, is president of The Matzevah Foundation, Inc., which cares for and restores Jewish cemeteries in Poland. He and his family live in Atlanta, GA.