Introduction

There are few examples today of leaders who use faith in the daily leadership of their organizations. Looking to the past for examples of great leaders who did deal with faith may be one way to offer suggestions for today’s leaders who either do not know how to incorporate faith into their leadership style or are afraid to do so.

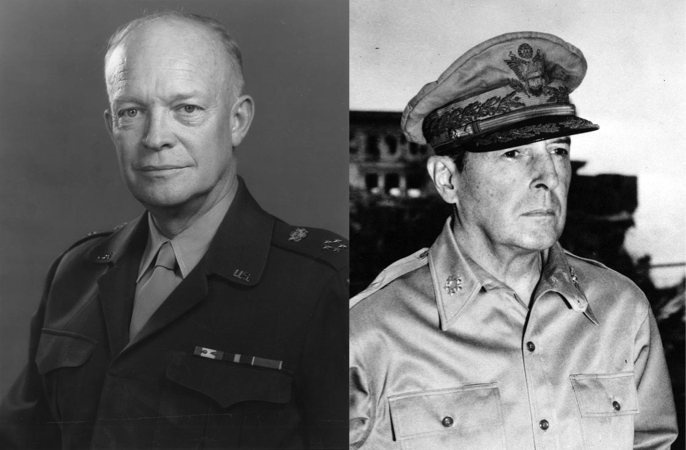

The lives of Douglas MacArthur and Dwight Eisenhower paralleled each other in many aspects. They were both influential figures who aspired for power on a national and international basis. Both were effective leaders who were respected and revered by most of their subordinates. They were highly skilled in using both the spoken and written word to lead their organizations. They also had careers that paralleled each other to some extent, with their assignments causing their paths to cross for over three years in the Philippines before World War II.

There are many instances of both generals invoking faith in their speeches, written orders, and leadership actions. Their use of faith in leadership is the main focus of this article; we will examine research that investigates the role faith had in both of their lives during difficult times and how each man’s faith may have influenced both their leadership style and decisions.

While much has been written on MacArthur and Eisenhower’s leadership and their relationship with one another, this researcher focuses specifically on how each man’s faith may have influenced both their leadership styles and the feelings they had for one another. The examples of how these two leaders used faith should encourage leaders today to analyze how they can better incorporate faith into their daily leadership activities.

Review of Literature Used

There is a great deal of research on both General MacArthur and General Eisenhower found across many different disciplines. Most are in the history field, but there is also quite a bit of research in the business and leadership fields. For this article, the author primarily used literature that viewed the two men from a historical perspective while also viewing them both in terms of their faith. Scholarly opinion of both men has varied over the years, from the very positive views of authors in the years immediately after World War II to the very critical analyses performed in the 1970s and 1980s. Since 2000, we have seen many more balanced reports from several authors, and it is this more recent scholarship that the author relied upon for the secondary sources used in this article.

For this article, many different sources were consulted including the more popular works performed on these two men, such as the book American Caesar by William Manchester, and Crusade in Europe by Dwight Eisenhower. Additionally, Schaller wrote a very critical work in 1989 entitled Douglas MacArthur: Far Eastern General. While this book provides an overview of MacArthur’s career from 1930 and onward, its view is very critical of almost everything MacArthur did. Schaller did not address the role religion had in the way MacArthur led (Schaller, 1989). When researching the impact religion had on both men, it was much more challenging to find information on Eisenhower because he lived most of his life trying to hide his religious upbringing (Bergman, 2000). This point will be discussed at length later.

The researcher relied mainly on primary sources to support the following assertions. Secondary sources helped provide an overview of the subject and in filling in any holes found in the primary source material. A majority of the primary source material for this article came from the Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives located in Norfolk, Virginia. The archives contain oral interviews, personal letters, written orders, speech transcripts, and many other types of documents dealing with Douglas MacArthur and other famous figures. Material from the archives served as the foundation for this article, in addition to diaries, autobiographies, and published speeches from both men.

MacArthur and Eisenhower in the Philippines

It is useful to evaluate the time MacArthur and Eisenhower spent together to understand the similarities and differences between these great men. As a major, Eisenhower served under MacArthur on two different tours. First, Eisenhower was hand-selected by MacArthur to serve under him in Washington while he served as Chief of Staff of the Army in 1930. Eisenhower was again selected by MacArthur to travel with him to the Philippines to serve on the staff of the American Military Mission. While their time in Washington went without many issues, their time in the Philippines showed their major philosophical and leadership differences and caused the rift between them that would last for the rest of their lives (Irish, 2010).

As time went on, the tensions between MacArthur and Eisenhower escalated. Eisenhower wrote of one such occasion in his diary:

TJ and I came in for a terrible bawling out over a most ridiculous affair. The general has been following the Literary Digest poll and has convinced himself that Landon is to be elected, probably by a landslide. I showed him letters from Arthur Hurd, which predicted that Landon cannot even carry Kansas; he got perfectly furious when TJ and I counseled caution in studying Digest reports. (Eisenhower, 1981, p. 46)

This change in the way he wrote about MacArthur in his diaries continued after he left the Philippines and went back to Washington to work in the War Department. In February 1940, Eisenhower wrote, “Looks like MacArthur is losing his nerve. I’m hoping his yelps are just his way of spurring us on, but he is always an uncertain factor” (Eisenhower, 1981, p. 47). A few days later he wrote, “Another long message on ‘strategy’ from MacArthur. He sent one extolling the virtues of the flank offensive. His lecture would have been good for plebes” (Eisenhower, 1981, p. 47).

It is evident that by this time, Eisenhower had more than enough of MacArthur and was beginning to see him more as a liability and laughingstock than a great leader. What we do not know is how his ill feelings towards MacArthur may have shaped his actions about his work at the War Department. Eisenhower wrote in his book, Crusade in Europe, about a conversation he had with General Marshall (Whitney, 1956). “General,” he said, “It will be a long time before major reinforcements can go to the Philippines, longer than the garrison can hold out with any driblet assistance.” General Marshall replied, “I agree with you” (Eisenhower, 1997). While Eisenhower knew of the lack of military reinforcements available to MacArthur, he never did let MacArthur know the truth: that he spoke freely with others about it. We can only wonder if this was due to his personal feelings or to military necessity.

MacArthur’s Leadership Style

Douglas MacArthur is arguably one of the most written about leaders of the modern era. While many authors dwell on his failures, there are almost as many who look past many of his faults. When we look at the interviews and words of those who worked for him, a slightly more consistent picture is revealed, but not one that is absolute. General Willoughby was confident that MacArthur would be successful in battle and staff work. He stated:

I knew he was a great Chief of Staff, one of the most effective Chiefs of Staff. I knew that he was far-sighted in the sense of developing certain branches of service or anticipating the modernization of armies. I knew that, and of course, these qualities would repeat themselves under the pressure of the wartime situation. (Oral History Collection, n.d.)

While it can be difficult to categorize past leaders with current leadership theory, the author will attempt to do so for both MacArthur and Eisenhower to better show how they differed in their approach and style. Douglas MacArthur fits very well into the transformational leadership category, except possibly in his lack of consideration for the individual. MacArthur’s ego has been discussed a great deal by authors, with some authors implying that he didn’t care about others while other authors are taking a gentler approach, writing that he only wanted to be appreciated (Kinni & Kinni, 2005, p. 117). Many of those who served with MacArthur placed him into the gifted leader category that we see present in the trait leadership theory. On this point, General Willoughby wrote:

Military quality or performance is not only craftsmanship, but also the intangible of an art. The great military commanders apparently shared certain characteristics without defining them as the cause of their greatness—apparently a gift. How do you explain the great commanders that survived the record of history? What made them great as commanders? That question would apply to MacArthur. There is a quality of leadership, or a talent, or a military art, which is apparently not as widespread as our training manuals indicated. (Oral History Dollection, n.d.)

General Diller also supported the superior leadership of MacArthur; Diller wrote:

General MacArthur’s ability to command was largely based on his own character. He was thoroughly disciplined himself, and he was totally loyal to his men and his officers. He gave loyalty before he asked for it and he never asked for it. (Oral History Collection, n.d.)

Of course, not everyone felt that MacArthur’s leadership was perfect and they, like Eisenhower, would probably not agree that MacArthur was a transformational leader who was always loyal. In a letter from the American Consul General to the Philippines in 1945, Paul Steintorf wrote, “General MacArthur made one rather cryptic statement to the effect that I would ‘please not spring any plots behind his back,’ I assumed that he meant that I was not to make any recommendations with respect to basic policy without first consulting him” (Goodman, 1996, p. 111).

This statement appears to show that MacArthur was paranoid while being worried about not being informed on the issues. This paranoia may have stemmed from being left out of many higher-level decisions, including the eventual use of nuclear weapons on Japan at the end of the war.

Other reviewers have attacked MacArthur based on his vanity and some of his poor command decisions. In MacArthur in Asia, Masuda and Yamamoto (2012) criticize MacArthur for not preparing well enough before the bombing of Clark Field in the Philippines, even though he had received information about the bombing at Pearl Harbor hours before. These authors also discussed MacArthur’s decision not to bomb Formosa immediately after the attack at Pearl Harbor, even after the Air Corps leaders reported that the theater B-17s were loaded, fueled, and ready to conduct such a mission (Masuda & Yamamoto, 2012, p. 36).

Ferrell (2008) attempts to relate MacArthur’s mistakes to his desire for acclaim in everything he did. He argues that this desire for praise led MacArthur to do many questionable things and make many wrong decisions. He states that this started at Côte De Châtillon, France in 1918 during World War I. Here the general allegedly claimed to have led his men into battle in order to garner praise and a Distinguished Service Cross, when in actuality he was never in the battle and over a mile away from the front lines at headquarters (Ferrell, 2008).

What is generally agreed upon about MacArthur’s leadership skills is that he was a gifted writer and orator who could inspire his men and the public alike. About MacArthur’s ability to reach an audience, Kinni and Kinni (2005, p. 116) write, “MacArthur’s greatest skill as an orator was this ability to connect to his intended audience. One way he accomplished this was by putting himself into his speeches, by personalizing the appeal.” MacArthur seemed to be able to connect with the audience so well because his delivery, gestures, posture, and vocal patterns were typically flawless. Even Eisenhower agreed that MacArthur was a gifted orator, writing, “He sometimes delivered public addresses of more than an hour in length without any notes whatsoever. However, he was not speaking extemporaneously. He always learned by rote his speeches” (Eisenhower, 1970).

In their book, No Substitute for Victory, Kinni and Kinni (2005, p. 117) point out that MacArthur’s most important skill as a writer and orator was his ability to reach his audience and make them feel like they shared the same issues as MacArthur. By connecting with his audience, he influenced those hearing him or reading his words to take on his way of thinking and support his cause. He did this by specifically personalizing his speeches (Kinni & Kinni, 2005). He also did this by repetition and the cadence seen in his speeches and written work. The best example of his use of personalization to inspire and cajole is seen in the speech he gave upon his return to the Philippines. In it, he wrote the following:

I have returned. At my side is your President, Sergio Osmena, worthy successor of that great patriot Manuel Quezon, with members of his cabinet. Rally to me! Let the indomitable spirit of Bataan and corregidor lead on. As the lines of battle roll forward to bring you within the zones of operations, rise and strike! For your homes and hearths, strike! For future generations strike! In the name of your sacred dead, strike! (Southwest Pacific Area, 1942-1945)

This speech is notable due to the personalization MacArthur included and for his repetition of the word “strike” as he implored the Filipino people to take up arms and join him in the fight for the country. While many authors would argue this is another example of MacArthur’s ego at work, one can’t deny the impact these words had on inspiring the downtrodden Filipino people to rise and take on the enemy.

MacArthur’s abilities to speak and write were used throughout his career to influence people and rally subordinates to follow his leadership. MacArthur wrote about his desire to have the media help him in his efforts in his diary from the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). On December 5, 1941, his official journalist recorded the following in his diary:

The general held a press conference at 9:45. All of the press, news services and local newspapers and magazines were present. The general outlined his policy if war should come. He stated that he would have a daily orientation conference and would accompany correspondents to the forward areas. He stated that coverage of this war would be more complete from a newspaper and photographic standpoint than any other war in the past. He outlined his policies and stated that restrictions would be held to the minimum. He thanked the press for the splendid cooperation to this point. (U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, 1941-1942)

It is difficult to know for sure if MacArthur desired this close relationship with the media to feed his ego or whether he understood how he could use the media to gain increased support for his leadership from his troops and the American public. It is likely it was a combination of the two, but there is no doubt that he understood how important the press was in spreading the story he wanted to tell and in gaining support for his ideas. MacArthur’s willingness to work with the media and his uncanny ability to get his story heard ultimately allowed him to spread his views on the role of Christianity to the nation during peace and wartime. Here he used his access to the media as a vessel to try and influence Americans to see how essential faith was to our nation, and ultimately, to our success in World War II.

Eisenhower’s Leadership Style

Eisenhower’s leadership style came from his middle-America upbringing in rural Kansas. The son of poor, highly spiritual parents, Eisenhower carried the idea of hard work and faith with him throughout his life. In the next section, the reasons why he at times hid his faith will be discussed, but there is no doubt that this faith did help to shape the way he led (Gilbert, 2010, p. 89). The impact of his family and rural values with which he was raised come through very clearly in Eisenhower’s diary from the day of his father’s funeral when he wrote:

My father was buried today. His finest monument is his reputation in Abilene and Dickinson county, Kansas. His word has been his bond and accepted as such; his sterling honesty, his insistence upon the immediate payment of all debts, his pride in his independence earned for him a reputation that has profited all of us boys. Because of it, all central Kansas helped me to secure an appointment to West Point in 1911. (Eisenhower, 1981, p. 51)

We can see that he respected his father and saw living up to the legacy of hard work and duty as something more important than almost anything else.

While raised in a hardworking home, Eisenhower did develop an even more compulsive drive for success as he aged. When Eisenhower arrived at West Point in 1915, he was already a determined and hardworking young man. The stress and rigor of West Point only served to heighten his ideals of sacrifice and hard work, while strengthening the way Eisenhower valued duty and responsibility to the organization. This was a slight change from what he saw in his father, who had worked hard for his family and his community. Eisenhower now saw that all groups needed a leader who understood the values of obedience and responsibility (Gilbert, 2010, p. 55).

Dwight Eisenhower’s leadership style fits well into what today’s leadership scholars term transformational leadership. He undoubtedly endeavored to encourage his subordinates to do more than the minimum required, and he valued their input. He also fits into what we would call situational leadership in the fact that he was able to vary his leadership style, depending on the conditions, to achieve the desired result. We can see this change in leadership behavior based on the situation in the different approaches Eisenhower took while in uniform and when serving as President. Herspring (2005) demonstrates this point best when he discusses how President Eisenhower led differently than General Eisenhower. On this topic, Herspring writes:

Eisenhower believed that he should primarily work behind the scenes, casting himself in a role that one presidential scholar has called the “hidden hand.” To the greatest extent possible, he desired to set general policy and then work behind the scenes to build political support for it. To achieve his goals Eisenhower favored persuasion over confrontation. (Herspring, 2005, p. 85)

This is a different, less hands-on style than Eisenhower had used dealing with a similar bureaucratic system during his military career.

Eisenhower appears to have been controlled by the sense of duty and responsibility instilled in him by his family and by his time at West Point. There are multiple occasions after Eisenhower left the army that he acted solely out this sense of duty. The first such occasion was when he was asked to serve as president of Columbia University. He at first declined, but then accepted after he saw that it was his duty to serve there and promulgate his thoughts on politics, as well as ideas on where the country should be headed. Next, he was offered the head position at NATO by President Truman. He again declined and told Truman he would have to order him to the position if he wanted him there. Truman obliged, and Eisenhower went on to serve as the NATO commander. Finally, Eisenhower was asked by Republican Party leaders to run for President. Here, “The general responded that he could never seek nomination to political office but ‘would consider a call to political service by the will of the party and the people to be the highest form of duty’” (Gilbert, 2010, p. 55). This sense of duty and obligation drove Eisenhower throughout his life.

Some historians counter this idea of duty being at the heart of what drove Eisenhower. Some have been critical, writing that it was more false humility than an actual call to obligation that drove Eisenhower. Others believe it was a case where Eisenhower may have been afraid of not being wanted that caused him to prefer to be ordered or called to his positions. Gilbert writes that Eisenhower at one point had attempted to design his own particular uniform as General of the Army so that he could separate himself and garner more attention (Gilbert, 2010, p. 55). This does not sound like a man who is modest and humble; instead it sounds a bit more like something General MacArthur would have done.

Eisenhower wrote in his diary about how important he might be as President of the United States. His words indicate his enchantment and excitement with the possibility. On the subject of a rally held for him, he wrote:

Viewing it finally developed into a real emotional experience for Mamie and me. I’ve not been so upset in years. Clearly to be seen is the mass longing of America for some kind of reasonable solution for her nagging, persistent and almost terrifying problems. It’s a real experience to realize that one could become a symbol for many thousands of the hope they have. (Eisenhower, 1981, p. 51)

You can almost hear Eisenhower’s giddiness in this diary entry, and likely he was excited about the opportunity. Gilbert takes his criticism even further when he wrote, “The unassuming ‘Everyman,’ therefore, gave clear evidence of having a well-developed and well-defined ego. Though seeming reluctant, he relished being pursued by political figures intent on making him President” (Gilbert, 2010, p. 55). As with many things, the truth about whether Eisenhower was hungry for fame and glory or was doing his duty likely lies somewhere in the middle. While his upbringing and military education made him understand obligation and responsibility, it does appear undeniable that he did crave some of the attention and accolades he received.

MacArthur’s Relationship with Faith in His Leadership

MacArthur had firm beliefs in a variety of subjects, but it appeared one of his strongest beliefs was in a higher power. While many point out that MacArthur never went to church as an adult (Seto, 2010, p. 26), it is evident from his words and his actions that he was a true believer. An article in Newsweek in 1943 put it bluntly, “His faith is life long, as is his avowed habit of reading a chapter of the Bible every night, no matter how tough his day has been” (Howard, 1897-1951). MacArthur was known to place God in almost every one of his important speeches and orders. A great example is his “Rally to me” letter to the Philippines, as previously mentioned. In the letter, he concluded with, “Let no heart be faint. Let every arm be steeled. The guidance of Divine God points the way. Follow in His Name to the holy grail of righteous victory!” (Southwest Pacific Area, 1942-1945).

MacArthur’s belief in God was shown even more apparent in his statement to the World Council of Churches on Flag Day, 1943. On this day, he said the following to the assembled group of Christian attendees:

Two thousand years ago a Man dared stand for truth, for freedom of the human spirit, was crucified and died. Yet this death was not the end, but only the beginning, to be followed by the resurrection and the Life. For twenty centuries, the story of the Man of Galilee has served for all Christians as lesson and symbol. So that today when our churches stress the spiritual significance of our united efforts to re-establish the supremacy of our Christian principles we can, humbly and without presumption, declare our faith and confidence with God’s help in our final victory. (Southwest Pacific Area, 1942-1945)

As Kinni and Kinni wrote in their book, MacArthur used speeches like this to connect with his audience; this use of the Almighty definitely would have helped him in connecting with his audience in this example (Kinni & Kinni, 2005). Many of his critics have said that MacArthur used faith to inspire those around him and to better prop himself up as a pious man. In the same Newsweek article previously cited, this notion seems to be dispelled by the quote from the reporter, who wrote, “The first inclination was to think that MacArthur was merely striving for effect in his statement, but this early reaction has long been forgotten” (Howard, 1897-1951).

Like most things in MacArthur’s life, his faith was full of inconsistencies and things most people could not understand. Worse than not being able to understand, his different behavior and way of practicing his faith gave people more ammunition to criticize him. Major General William Beiderlinden when interviewed, stated somewhat condescendingly that MacArthur “was reputedly an Episcopalian” (James, n.d.). When pressed if MacArthur had any interest in the concept of church Beiderlinden stated, “I’m positive he didn’t” (James, n.d.).

However, it is well documented that MacArthur’s wife, Jean, attended church services regularly. We see proof of this in interviews with many of MacArthur’s acquaintances. The question is: why did MacArthur not worship in a similar, what we might call “normal” way? Seto (2010) may have explained MacArthur’s faith best when he wrote, “Although Douglas MacArthur spent his entire life as an Episcopalian, he did not personally favor church-going or institutional worship. Instead MacArthur preferred a more personal relationship with God derived from personal prayer and Bible study, often with his family.”

MacArthur’s personal physician for many years, Dr. Egberg, described MacArthur’s faith in similar terms as Major General Beirderlinden. His description is kinder but still displays the inconsistency in the way MacArthur practiced his faith. In an interview when asked what he believed MacArthur thought about God, he stated:

Well, I think he thought of God as omniscient and an ally. Somebody that he respected as a powerful force, at least I think he did. And, somebody that he felt was terribly important to a large part of our population therefore to the soldiers and to their families. One experience does come to mind. At the end of one of the campaigns in Leyte he had written an order of the day which is thanking everybody who participated for helping in the campaign, and he would sometimes dictate to me and I’d written it down, and he said, “Go out and see if you can’t get a clerk out there to type this so we can read it over.” And I hadn’t gone far out of his office before he said, “Doc, Doc, come back.” So I went back and he looked at me and he said, “We forgot God.” So I sat down and took some more notes and we remembered to thank God. Now you may think that is funny but I think he felt it was important to the soldiers and their families that he’d be aware of God. Now it may have been a pragmatic way of looking at God. He never went to church. Jean went to church. Mrs. MacArthur went to church and I went with her a number of times and she liked to go to a service, he never went to one. (Oral History Collection, n.d.)

This statement from Dr. Egberg points out the inconsistency that people have frequently spotted when evaluating MacArthur’s faith.

It is possible that MacArthur honestly preferred to be with God by himself and did not want a “middle man” in between him and God. It might also be that MacArthur believed he knew more than most of the learned men in the church and preferred to make up his own mind on Biblical interpretations. This would not be too far off what MacArthur was like in terms of other subjects, as this was how MacArthur treated other topics, such as military strategy and politics. He preferred to research the issue and be right on it.

MacArthur did seem to increase the intensity of his faith as he got older. In 1951, he said, “I am a great believer in prayer. My men pray. The soldier carries out the teaching of Christ which stresses the necessity of sacrifice. His life is one of constant sacrifice. It becomes a soldier to seek solace in prayer. I pray myself” (Lowe, 1950-1951). With statements like this, it is difficult to deny that MacArthur was a devout follower of Christianity.

Many biographers believe the more war MacArthur saw, the more he longed for peace. It may have been this longing for peace that increased his expression of faith since MacArthur believed that God could bring peace. General MacArthur’s pilot, Colonel Rhodes, described this:

I think he really felt that he had a job to do and the Almighty was going to see that he got it done. He would not express it in so many words very often but he took undue chances. He did things that no self-respecting human being would do who was normally afraid of what was happening. I think he sincerely felt that his mission was to get this war over with and he exhibited this scorn for danger time and time again to the great worry of all of his troops and his subordinate commanders. (Oral History Collection, n.d.)

Another interesting thing about MacArthur’s relationship with faith is that it started to appear more after the end of the war while he was the Supreme Commander of Japan. It was during this time that his belief that democracy and Christianity were virtually synonymous came to the foreground. MacArthur had spoken of the relationship between democracy and Christianity before, but he had mentioned how democracy allowed for religious freedom more than the relationship between Christianity and our system of government. An example of this is in his response to The World Tomorrow in 1931; he wrote:

Perhaps the greatest privilege of our country, which indeed was the genius of its foundation is religious freedom. Religious freedom, however, can exist only so long as government survives. To render our country helpless would invite destruction, not only for our political and economic freedom, but also our religion. (Wittner, 1971, p. 24)

This is a far cry from many of the statements he would make in post-war Japan and during later years back in the United States. In addition to his movement away from saber-rattling, he also moved clearly into the opinion that Christianity helped democracy to flourish, in addition to democracy helping freedom of religion to exist.

When tasked with rebuilding Japan, MacArthur found a nation that did not have a background in democracy for its people to draw upon as a support for the new political system the West wanted them to have. They also did not have a secure faith system beyond faith in the emperor. MacArthur saw Christianity as the solution to supporting the implementation of democracy in Japan. He welcomed many denominations and their missionaries to Christianize Japan.

MacArthur had grown to see Christianity and democracy as the same thing and believed that by having both they could help one another flourish in Japan. His conflation of these concepts was to such an extent that during his time in Japan, he rarely used them alone in any of his speeches (Seto, 2010). By this point, the General’s words on the relationship between Christianity and democracy were much different than what MacArthur had written in 1931. On this subject he wrote, “Democracy and Christianity have much in common, as practice of the former is impossible without giving faithful service to the latter” (U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, 1941-1942). It appears that MacArthur had come from believing that the state was more important than protecting Christianity, to now seeing Christianity as the one thing that would save democracy, or in the case of Japan, allow the political system to grow.

Eisenhower’s Relationship with Faith in His Leadership

In yet another parallel to the leadership and life of MacArthur, Eisenhower had a very complicated relationship with his faith. Raised by Jehovah’s Witnesses, Eisenhower spent most of his time in the Army trying to distance himself from this fact. He tried to hide the origin of this faith because Jehovah’s Witnesses are committed to peace and do not believe the American flag should be saluted or that the Pledge of Allegiance should be recited since this would put something above God. They were also conscientious objectors—a fact that would be very embarrassing to a high-ranking, wartime Army General. Eisenhower only became religious once he ran for President of the United States. This has caused many to say he was using Christianity as a vehicle to increase his chances of getting elected and to advance his agenda once in the White House (Bergman, 2000, p. 89).

With his parents being Jehovah’s Witnesses, there is no doubt that Eisenhower was raised in a fundamentalist Christian tradition. However, Eisenhower and his brothers never practiced or participated in this denomination after they left home, and Eisenhower tried very hard to hide his parents’ faith even after they died. When his father died, Eisenhower did not attend the funeral. The service was in a church, and as such, reporters could easily tell the denomination of his father. When his mother died, Eisenhower attended, but ensured the ceremony was only open to those who were invited; additionally, he ensured that an Army chaplain conducted the funeral ceremony of his mother. While Eisenhower did not speak of his parents’ faith much, he did write about it in 1967:

There was, eventually, a kind of loose association with similar groups throughout the country . . . chiefly through a subscription to a religious periodical, The Watchtower. After I left home for the Army, these groups were drawn closer together and finally adopted the name of Jehovah’s Witnesses. They were true conscientious objectors to war. Though none of her sons could accept her conviction on this matter, she refused to try to push her beliefs on us just as she refused to modify her own. (Bergman, 2000, p. 89)

This admission late in life appears to confirm that Eisenhower had attempted to cover up his parents’ faith. This argument is even stronger when you consider that Eisenhower had told many people that his parents had been Mennonites in a blatant attempt to shield himself, and his family, from potential criticism.

The fact that Eisenhower hid his faith background for many years is very inconsistent with what he did once he became President of the United States. Many scholars see him as doing more to bring Christianity together with democracy than any president before or since. Gunn and Slighoua (2011) go as far as to say that, “The eight-year Eisenhower presidency was unprecedented in American history for its introduction of religious language and symbols into political life” (p. 40). It was during his two terms as president that we saw the addition of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance, and “In God We Trust” to our currency. During his two terms, the first Presidential Prayer Breakfast was instated, as was the National Day of Prayer. Additionally, Eisenhower invoked God in most of the speeches he gave.

Like MacArthur, Eisenhower came to see our nation highly intertwined with Christianity. On this subject he stated:

We have begun in our grasp of that basis of understanding, which is that all free government is firmly founded in a deeply felt religious faith. I think my little message this morning is merely this: I have the profound belief that if we remind ourselves once in awhile of this simple basic truth that our forefathers in 1776 understood so well, we can hold up our heads and be certain that we in our time are going to be able to preserve the essentials, to preserve as a free government and pass it on, in our turn, as sound, as strong, as good as ever. That, it seems to me, is the prayer that all of us have today. (Gunn & Slighoua, 2011, p. 40)

The question is: did Eisenhower use his faith to gain a strategic advantage, or did he see later in life that he was safe to live out his faith as he would like? The evidence shows that there may have been a little of both behind his actions. Eisenhower wrote in his diary in 1953 after taking office:

Mamie and I joined a Presbyterian church. We were scarcely home before the fact was being publicized, by the pastor, to the hilt. I had been promised, by him, that there was to be no publicity. I feel like changing at once to another church of the same denomination. I shall if he breaks out again. (Eisenhower, 1981, p. 226)

From this account, it seems that Eisenhower wanted to pursue his faith in private for other reasons than protecting his career.

Comparison of MacArthur and Eisenhower’s Use of Faith in Their Leadership

Like many areas of the lives of these two men, at first glance, it appears that their use of faith in their leadership was very different. Eisenhower never discussed his faith while in uniform, while MacArthur discussed it at every chance possible. However, beyond this difference, there are quite a few areas where the two had similar practices when it came to how faith impacted their lives. While neither went to church, they both had solid religious roots. Eisenhower’s came from his upbringing, and MacArthur’s came from reflection and selfstudy. Neither of them believed in the strict structure of the institutional church, although Eisenhower appeared to warm up to this notion as President.

Arguably most signigicant similarity between MacArthur and Eisenhower’s views on faith can be seen in how they both came to see democracy and Christianity as linked. Eisenhower began to see this relationship as he was running for President, while MacArthur saw it as he attempted to democratize Japan. It can also be said that both men were somewhat pragmatic when it came to religion. While it was likely not their sole motivation, both did use religion, specifically Christianity, to help them in their jobs as leaders.

Conclusion

Dwight Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur are two of the most important men of the 20th century. Their lives as leaders spanned multiple wars, changes in political and economic situations, and significant changes in American society. Due to their importance to America and the world, much has been written about their lives and their leadership style. The literature on the two men is evenly split between criticism and praise for how they led during their time in power. In recent years, researchers have treated both with more balance, showing both their weaknesses and their strengths.

While there has not been very much analysis of how these two men led with Christian faith, this author has attempted to point out some information about these two men that might lead to further research. It would be fascinating to analyze further how Eisenhower and MacArthur used faith by reviewing additional public response to their expressions of faith.

References

Bass, B. (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership. New York, NY: Free Press.

Beebe, L. C. (n.d.). Record group 34, diary of General Lewis C. Beebe, USA. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Bergman, G. (2000). The influence of religion on President Eisenhower’s upbringing. Journal of American Culture, 23(4).

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York, NY: Harper.

Eisenhower, D. D. (1970). The papers of Dwight David Eisenhower. A. D. Chandler & L. Galambos (Eds.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press.

Eisenhower, D. D. (1981). The Eisenhower diaries. R. H. Ferrell (Ed.). New York, NY: Norton.

Eisenhower, D. D. (1997). Crusade in Europe. London, UK: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ferrell, R. H. (2008). Question of MacArthur’s reputation: Cote De Chatillon, October 14—16, 1918. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Gilbert, R. E. (2010). Dwight D. Eisenhower: The call of duty and the love of applause. The Journal of Psychohistory, 38(1), 49—70.

Goodman, G. K. (1996). A meeting with MacArthur 20 March 1945. Philippine Studies, 44(1), 105—112.

Gunn, J., & Slighoua, M. (2011). The spiritual factor: Eisenhower, religion, and foreign policy. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 9(4), 39—49.

Herspring, D. (2005). The Pentagon and the presidency: Civil-military relations from FDR to George Bush. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Howard, H. P. (n.d.). Record group 41, selected papers of Brigadier General Harold Palmer Howard, USA. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Irish, K. (2010). Dwight Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines: There must be a day of reckoning. Journal of Military History, 74, 439—473.

James, D. C. (n.d.). Record group 49, D. Clayton James collection. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Kinni, T., & Kinni, D. (2005). No substitute for victory: Lessons in strategy and leadership from General Douglas MacArthur. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lowe, F. E. (1950—1951). Record group 37, papers of Major General Frank E. Lowe. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Manchester, W. (1978). American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880—1964. New York, NY: Back Bay Books/Little, Brown and Company.

Masuda, H., & Yamamoto, R. (2012). MacArthur in Asia: The General and his staff in the Philippines, Japan, and Korea (1st ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Medhurst, M. (1994). Eisenhower’s war of words: Rhetoric and leadership. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

Northouse, P. (2009). Leadership: Theory and practice. London, UK: SAGE.

Office of the Military Secretary. (n.d.). Record group 5, Subseries 4. retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Office of the Military Secretary. (n.d.). Record group 5, Box 37, Subseries 4. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Oral history collection. (n.d.). Record group 32. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Prefer, N. (1995). MacArthur’s New Guinea campaign. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books.

Seto, B. (2010). Filling the spiritual vacuum: Douglas MacArthur, American Christianity and the occupation of Japan. (ProQuest Dissertations).

Schaller, M. (1989). Douglas MacArthur: The Far Eastern general. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). (1942—1945). Record group 3, records of headquarters. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). (1941—1942). Record group 2, records of headquarters. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Whitney, C. (n.d.). Record group 16, papers of Major General Courtney Whitney, Series 1. Retrieved from Douglas MacArthur Memorial Archives, Norfolk, VA.

Weintraub, S. (2007). 15 Stars: Eisenhower, MacArthur, Marshall: Three generals who saved the American century. New York, NY: Free Press.

Whitney, C. (1956). MacArthur: His rendezvous with history (1st ed.). New York, NY: Knopf.

Wittner, L. (1971). MacArthur. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Dr. Steve Firestone serves as an assistant professor at regent University’s School of Business and Leadership, and serves as the Director for the M.A. programs in Organizational Leadership, Church Leadership, and Not-for-profit Leadership. He retired from the U.S. Navy after 23 years of service as an officer, naval aviator, and educator. As a pilot, Firestone flew helicopters on two Arabian Gulf deployments and C-130 transport aircraft around the world on a variety of missions and deployments. He has extensive experience working with foreign military organizations having served as a liaison officer to Mexico, Canada, and the Bahamas. Dr. Firestone graduated from Vanderbilt University with a B.A. in history and a B.A. in Political Science. He has a Master of History from Southwestern Assemblies of God University, an MBA from Embry-Riddle University, and earned his Ph.D. in Business Administration, with an emphasis in Organizational Leadership from Northcentral University.