Abstract

This article describes the findings from a study analyzing the common understandings of national, regional and church planting leaders for the commitments and practices that support keeping mission at the center of the church’s being and purpose. Three core commitments were discerned to be essential to mission vitality: 1) trusting in narrative-based ways of knowing, 2) witness shaped by holy hospitality, and 3) welcoming fresh expressions of the new humanity rather than settling for like-mindedness. These commitments are illustrated with the story of Missio Dei, a new Mennonite church planted in the Cedar Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis.

Keywords: Church, mission, missional theology, church planting, leadership, witness, mission as hospitality, contextualization, narrative understanding, theological education, leadership development.

Planting an Intentional Community

In 2004, Mark and Amy Van Steenwyk moved to the Cedar Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis to start a new church. In the first attempt, the church grew to about 50 people. Mark recalls that “most of the people lived in the ‘burbs, hung out in the ‘burbs, and only came to the neighborhood for a Sunday gathering.” After their first attempt to plant a church did not result in a congregation rooted in the Cedar Riverside context, Mark and Amy went back to the drawing board to found a neighborhood-based, intentional community called Missio Dei. To do so, the first commitment Mark and Amy made was to live in the neighborhood for two years implementing no strategic initiatives to first see how the neighborhood would “host” them as members of the community. Missio Dei’s website champions the outcome of this strategy: “Out of the ashes of what once was, a new church emerged—a community anchored in the neighborhood and centered on Jesus’ way of peace, hospitality, simplicity, and prayer.”

The Cedar Riverside neighborhood consists of immigrants, refugees, punks, artists, homeless people, students, activists and professionals. It is the most densely populated square mile between Chicago and Los Angeles, containing close to 9,000 economically and ethnically diverse residents. More than 2/3 of the neighborhood is low-income or live below the poverty level.

The community life of Missio Dei centers around three households in which some of the members choose to live. Missio Dei is an expression of the “new monastic” movement in the church planting field. In the tradition of new monasticism, the members of Missio Dei commit themselves to a rule for their common life. The preamble of this rule says,

Missio Dei is committed to Jesus’ way of peace, simplicity, prayer and hospitality. Missio Dei lives to embody Jesus’ presence–particularly in this neighborhood. Members of Missio Dei commit themselves to three things: centering their lives on Jesus Christ, being present to the neighborhood, and sharing their lives with one another.

On Saturdays from noon until 4:00 p.m., the community participates in what has come to be known as the “Hospitality Train.” The community loads up their bike trailers with fresh ingredients and high-quality cooking equipment to feed people good food at a vacant lot that they observed to be a gathering place for some in the neighborhood. Increasingly, musicians come and play while the meal is being served. It has become a place where the diverse segments of the neighborhood gather. It also brought them under close scrutiny of homeland security officials during the Republican National Convention. More on that incident later.

The leaders of Missio Dei understand that God’s mission precedes human initiative. Amy says, “None of the people who helped to start Missio Dei had any background in the neighborhood, so we really wanted to see where God was at work and submit ourselves to the neighborhood.” This attention to God’s preceding mission resulted in the church’s decision to dovetail with existing initiatives in the community. Church leaders spoke of trying to learn from the neighborhood and then asking God to show them where He is working and where He wants them to get involved.

Church planters Mark and Amy tie the ideas of God’s preceding mission and hospitality together as a single value. Hospitality for this church is not only something offered, but also something received. The vision of leaders at Missio Dei reacts against modern church patterns that limit the common life experience to Sunday morning worship and mid-week programming. Mark emphasizes the importance of being clear about the community’s “rule” as people come to explore the church: “We have a standard [articulated] that we’re calling people toward. So if one person doesn’t engage as much as someone else, it’s still the same standard we’re working toward.”

Reflecting on the challenges postmodern views of reality pose to mission, the leaders of Missio Dei and other developing congregations are experimenting with new approaches to contextualizing ministry. These new congregations are being born in a missional frame in which leaders understand mission as participation in the sending of God rather than originating in the imagination of the church. The church’s mission has no life of its own. In this concept of mission, mission is not primarily an act of the church but “an attribute of God” (Bosch, 1991, p. 390). The nature of the church is no longer understood in imperial terms seeking to normalize Christianity in society. Mission is the center of the church’s very nature. Through interviews and document analysis of a number of developing churches, I found three core commitments that the leaders of these communities make in order to keep mission at the center of community life (Boshart, 2010). These same commitments are essential for any church that hopes to keep mission at the center of its nature and purpose. These commitments are 1) trusting in narrative-based ways of knowing; 2) witness shaped by holy hospitality; and 3) welcoming fresh expressions of the new humanity rather than settling for like-minded- ness. These learnings are as relevant for leaders of existing congregations as they are for those of developing ones. But first let us consider some basic implications about the nature of church and mission in the opening years of postmodernity.

The Church and Mission for Our Times

In order for the church to meet the challenges posed today it needs, in the words of Wickeri (2004),

a kenosis (or self-emptying) of mission so that [it] can once again become part of a movement in society that shakes up institutions and calls them to renewal. Our structures need to be more pluriform and decentralized. In the future, the church may have a lower visibility than it now has; it may, at times, become more “hidden” in social movements. This is part of the missio Dei. (p. 197)

Missional theology is an attempt to meet this challenge. Missional theology is a relatively new development in churchly conversations, though it has been a developing paradigm for missiology and ecclesiology since the first third of the 20th century. Building on early work of Karl Barth and Karl Hartenstein, missiologist David Bosch (1991) proposed that this way of speaking about mission resulted in a new theological paradigm “which broke radically with an Enlightenment approach to theology” (p. 390):

The classical doctrine of the missio Dei as God the Father sending the Son, and God the Father and the Son sending the Spirit was expanded to include yet another “movement”: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit sending the church into the world. (p. 390)

Borrowing from Lesslie Newbigin, to extend this paradigm, missiologist Art McPhee (2001) writes that God’s people are involved in mission not out of obligation but out of a new identity.

When Jesus said, “You will be my witnesses” (Acts 1:8), he was not issuing a command but making a statement about the nature of his followers. Likewise the New Testament’s metaphors for believers— salt, light, fishers, stars, letters, ambassadors, good seed—are never made in the imperatives. They are always indicative [emphasis mine], attesting that mission is the natural activity of the church. (p. 10)

The Marginalized Power of the Church in Society

Mainline Protestant and evangelical groups are for the first time trying to understand what it means to be the church in a North American society where the church’s power is marginalized. Barrett (2006) celebrates this reality as a sure sign of the end of Constantinian Christendom. This liberates the church to pay closer attention to the church’s context and the needs of the world:

Freed of the need to make things come out “right” for the government or society or to feel at home in the culture, the missional church can live out its understanding of the gospel of Jesus Christ. The church can have a different worldview. It can become an alter- native community. It is different from the world, not for the sake of being different, but because it is seeking to conform to the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, rather than to conform to the surrounding culture. (p. 181)

Echoing the developing missional paradigm grounded in the Trinity, Barrett (2006) concludes that “the witness of the missional church is always grounded in the gospel of Christ, initiated by God, and led by the Holy Spirit” (p. 182). Working in England, a context of acute post- Christendom, church planting expert Stuart Murray (2000) understands missio Dei and its resultant missional church in similar terms. The broad work of missio Dei should not be reduced to evangelism or church planting. Rather missio Dei calls forth a church that not only proclaims the good news, but is good news.

The Church in Mission: Native and Stranger

Many churches in the West have become institutionalized to the point that the preservation of the tradition, or institutional identity, competes in influence with the needs and opportunities presented by the context of mission. On the other hand, attempting to normalize Christianity in the wider society has caused the church to reflect cultural attributes that may very well be “unchristian” in the name of “relevance.”

Missiologist Andrew Walls (1996) suggests that the effectiveness of the church in mission will depend on managing two principles that are in tension with each other. The first principle, the indigenizing principle, suggests that “the Gospel is at home in every culture and every culture is at home with the Gospel” (pp. 6-7). The other principle is the “pilgrim” principle which suggests that “the Gospel will also put us out of step with society” (p. 8). In the past, the church has been tempted to define its mission by imposing one or the other of these principles as the defining mode of operation. Holding these principles in tension, though difficult, leads the church in mission away from social and cultural conquest on the one hand, and isolating irrelevance on the other. In the dialectic of these two principles, we find that the church in mission will be both distinctive and engaged (Murray, 2000).

When mission is not conceptualized in this dialectic, we might consider how churches will regress into stagnation by examining four possibilities where distinction and engagement are concerned (see Table 1).

Table 1. Four Types of Churches Based on the Interaction of Engagement With the Context and Distinction From the Context

| Low Distinction from Context | High Distinction from Context | |

| High Engagement with Context | High Engagement

Low Distinction (Church as therapeutic spa) |

High Engagement

High Distinction (Mission at the Center) |

| Low Engagement with Context | Low Engagement

Low Distinction (Church as Coffee shop) |

Low Engagement

High Distinction (Cloistered Convent/Amish?) |

Indistinct from the context yet disengaged with the context. This model of church might be caricatured as “coffee bar church.” In this model, the doors are open to everyone with the promise that each person can customize what the church is serving to each one’s particular tastes (think here “double soy, half caff, mocha latte with chocolate sprinkles”). The customer comes in from the street, gets her take on the Gospel and is sent out to continue down the same path of life she has chosen. The church in this model reflects all the cultural thirsts of the culture while effecting no moral distinctions in the lives of those who patronize it and no hope for changing the world beyond the church’s threshold.

Indistinct from the context and engaged. This model of church might be caricatured as “day spa church.” In this model, the church projects the hope for an idealized life lived by the idealized person. So the church advertises that everyone should come and participate in the hope that all who participate will reflect the human ideal, rather than life in God’s reign.

Distinct from the context disengaged from the context. This model of church might be caricatured as a monastic convent. In this model, members live a life very distinct from those in the surrounding context but those in the church remain walled off from the influences of that same context. The influence of this church is expected to come from spiritual activities practiced behind closed gates. Arguably, we might talk about the Amish as an example of this model of church. The Amish are distinctive in countless ways from the surrounding context and do not seek to engage that context. In spite of being disengaged from the context, the distinctiveness of the community does produce some residual, though not strategic, witness as seen in the tourists who come by the busloads to watch this community live out its peculiar lifestyle.

Distinctive from the context yet engaged with the context. In this model, mission is at the center of the church’s being and purpose. In the church led by the Van Steenwyks, we see an example of this pilgrim and indigenizing dialectic at work. Here we have a community of believers who have adopted a “rule” of life that inherently contrasts with the surrounding culture. Yet, this community of believers seeks out the places where they might be welcomed and then begin to catalyze hospitality in a way that naturally makes sense to those who live in the context. It also results in the “distinction” of being scrutinized by the powers of this age.

Marks of the Mission-Centered Church

Current social trends pose dramatic challenges to ways of doing mission for traditional denominations. Ecclesiologist Craig Van Gelder (2005) chronicles the shifting roles that denominations have played since the Protestant Reformation. The question of identity and function of the church has been focused by recent decades of declining denominations (p. 30). According to church historian Layne Lebo (2001), one historic denomination finds itself wrestling with the tension of retaining the foundational values upon which the denomination was based while at the same time responding to a context that is asking for new forms. Lebo raises the question of competing influences in historic denominations. Which factor will be the dominant influence and shaper of the church’s work: identity or mission? This question describes well the crucible in which denominations function in a post-Christendom context. Missional theology would suggest that this question poses a false dichotomy: the identity of the church is mission.

The missional church understands that the mission of God to reconcile all things is His work. Rather than believing that the kingdom is manufactured by the church, as Social Gospel proponents suggest, the church’s role is to bear witness to God’s work already breaking forth in the world. As Kreider, Kreider, and Widjaja (2005) have said, “After all, our mission as Christians is not primarily to bring solutions to the world’s problems, but to bring hope for redemption” (p. 79). The church takes up residence at the places yet to be reconciled to God to proclaim and be a sign of the reign that He is bringing to bear on all creation. We might consider several marks of the mission-centered church in Table 2.

Table 2. The Marks of a Mission-Centered Church

| Anti-Missional Reflection | Positive Missional Reflection |

|

|

Three Core Commitments

In analyzing the stories of developing churches and in interviews with national and regional church leaders trying to grasp missional theology, we are able to identify three core commitments that are essential in keeping mission at the center of the church’s being and purpose.

Core Commitment #1: Trusting Narrative Ways of Knowing

At Missio Dei, the members of this new monastic community have adopted a “rule” by which they commit themselves to three things: centering their lives on Jesus Christ, being present to the neighborhood, and sharing their lives with one another.” By its very definition a “rule” is an absolute orientation of the heart that precedes all other commitments. The life of the church will be a Spirit-empowered dramatic participation in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus in the world (Guder, 2007).

Karl Barth said that the church is “directed every day, indeed every hour, to begin again at the beginning” (quoted in Kroll, 2008). Our beginning points determine the shape of our reality. In our time there are many competing ways of knowing. Since the Enlightenment experience, reason, and the scientific method have enjoyed god-like power in our society. The scandal of the cross, however, is that we have this God who did this unreasonable, unimaginable and unprovable thing: God became flesh and dwelled among humans, lived human life, and died human death. Though the church has often been tempted to conform her strategies to what statistics tell us and what science has “proven,” the future of the church in mission can never be based primarily on empirical, evidence-based prescriptions. The church that seeks to embody the life, death and resurrection of Jesus learns how to be in the world by dwelling on and re-enacting his story.

For the church, the Scriptures provide a narrative-based way of knowing. Christians have traditionally constructed their understanding of reality through the big story (a metanarrative) that names “God” as the really real. In the Scriptures, this God is presented as the one who has been most fully revealed in the Word made flesh, that is, Jesus (John 1:14). The New Testament presents Jesus as the full way of knowing God in the Gospel and Epistles. Jesus said, “If you know me, you will know the Father” (John 14:7). The witness of the Colossians concurs: “In him the fullness of God was pleased to dwell” (Colossians 1:19). Though many Christian historians have attempted to reconstruct a historical Jesus, the church has routinely insisted that apart from the Biblical narrative it is not possible to know the mission of God as revealed in and through Jesus. Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder (2001) argued that this way of knowing is central to the church’s being: “The presence of the text within the community is an inseparable part of the community’s act of being itself”; and that “it would be a denial of the community’s being itself if it were to grant a need for an appeal beyond itself to some Archimedean point to justify it” (p. 114). Trusting this narrative way of knowing keeps the church’s identity distinct and engaged. It both reminds the church who she is in bas-relief to the surrounding culture while at the same time helping the church to discern the very places to be present as a sign to the world of the hope for redemption.

In a cultural context that increasingly reflects a post-Christendom reality, narrative ways of knowing bring a witness that can bring hope in pro- found ways in our time. For postmoderns—there is no grand story. Even an individual’s story does not provide a means of knowing. What a postmodern “knows” is whatever one can glean from one’s set of seemingly random, idiosyncratic, unfolding experiences. Ironically, this way of knowing leads many to an anxious, exhausted, disillusioned and world- weary existence. The pervasive nature of this phenomenon in youth and young adult culture has been described poignantly in Anne Lamont’s recent novel Imperfect Birds (2010). The pursuit of meaning through reflecting on random, unfolding experience leaves many in our culture yearning for a story that means something.

The church in mission understands that at the center of God’s big story is mission: God’s mission of reconciliation and redemption. Theologian Harry Huebner (2005) expresses it this way: “Christians believe that since gracious God created the world, peace and wholeness are ontologically more fundamental (more real) than sin, violence and brokenness. The brokenness, sin, violence and injustice around us, although real, are transitory” (p. 98). Here is a word of great hope for a world yearning for life to mean something. Our means of bearing witness to what we know need to be aligned with our ways of knowing in order for that mission to be coherent.

At Mission Dei, the Van Steenwyks seek to embody this coherence of bearing witness to what they know and their ways of knowing by centering their lives on Jesus Christ through careful reading of the Gospel in a dialectic that moves from Gospel to life and life to Gospel. The community has published its own breviary to guide the community members in their morning and evening prayers. They strive to be present to people on the edges of society in the way of Jesus. The members also seek to live a life of humility and modesty in contrast to an affluent society. The members agree to forsake violence in all its forms and instead seek and promote peaceful ways of resolving conflict. One of the leaders of this congregation expressed the church’s attempt to align their being with the means of witness this way:

We try not to see doing some sort of service that’s abstract from Christ, but instead, we’re actually trying to live with Jesus [in the present], because we believe that Jesus is creating these things, and doing these things, and his kingdom exists, and this is what it looks like. We’re trying to live that, we’re not trying to just go off and do our own thing because of some sort of individual belief.

Commitment # 2: Witness Shaped by Holy Hospitality

In our postmodern privatized society that idolizes the individual, we tend to think that it is normal to want to be left alone, especially where religion is concerned. This is a place where our world needs to be demythologized. The grand narrative of Scripture presents human need and desire differently. People don’t want to be left alone. They want community. They want communion and engagement with an ultimate being. Part of reflecting God’s image is a desire to reflect the communion that goes on in the Trinity. It’s easy for us to think, “Nobody wants to die alone.” The belief that people want to be left alone is more a sign of our brokenness. The point of God’s mission is to reconcile all things by breaking down walls of hostility and joining all people together into a dwelling place for God’s Spirit (Ephesians 2:11-21).

In Luke 10:1-24, we see the means by which Jesus trained the Twelve for mission. The disciples are sent out with no personal resources. (This is not the same as pretending you don’t have strengths or giftedness or for that matter interests.) They are to accept the hospitality of the stranger and announce “peace.” They are to “get hosted.” One of the most radical things about this story is that the hospitality of the stranger is the platform for witness. The disciples are to announce that the kingdom of God has come near. Then out of the observable need revealed because one has been hosted, one offers a sign of God’s reign where reconciliation, healing, restoration, and wholeness are desperately needed. At Missio Dei, the Van Steenwyks gave attention to God’s preceding mission resulting in the church’s decision to dovetail with existing initiatives in the community rather than creating new ones. Amy Van Steenwyk reflects on the community’s deliberate choice to rely on the hospitality of the stranger as the platform for witness: “Instead of starting an ESL [English as a Second Language] course or program, I volunteered at one already in existence. Instead of starting our own [bike] cooperative, Jason works on bikes and builds bikes at an existing bike cooperative.”

By allowing themselves to be hosted in their contexts through means already in existence, these church leaders are experiencing exponentially more avenues for relationships than if they were creating a limited number of church-initiated and owned ministries. These leaders see the hospitality offered in their context as the means of discerning where God is working and how they can align their witness with God’s purposes.

Hospitality is often described in missiology from the perspective of hosting the stranger into the church’s space (Barrett, 2004; Guder, 1998; Keifert, 1992, 2007). But hosting the stranger into the church’s space often reinforces a pattern where the one who enters the space of “the regulars” will always remain a newcomer (more on this under commitment #3).

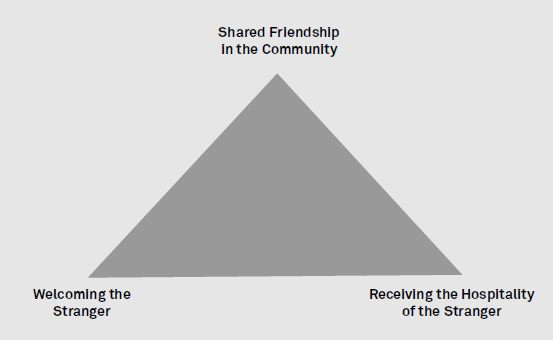

In analyzing collected stories from developing congregations, one discovers a common understanding of three-dimensional hospitality within which Christian witness best happens (see Figure 3). Two of these dimensions of hospitality are rather conventional: (1) demonstrating hospitality in the common life of the church members and (2) welcoming the stranger. But there is another dimension of hospitality that precedes the other two and can easily be overlooked when churches are being planted: a prior commitment to receiving the hospitality of those in the context in which one is planting the church. Says Jason, “Before you plant a church you need to submit to the neighborhood for awhile first. So ideally, someone should just work and live and hang out in the neighborhood for at least a year before they even start doing anything tangible as far as ministry so that you really understand where you are and, by extension, what God is doing.”

Being received by the stranger is the first movement of a church whose mission is aligned with God’s mission. Figure 1 implies that without the prior commitment to receive the hospitality of the stranger, the mission of the church will default to transactional rather than transformational forms of ministry.

Figure 1. Dimensions of hospitality of the church in mission

Why is it important—and Trinitarian—to see receiving the hospitality of the stranger as the first movement in mission? Because it ensures that God’s offer of reconciliation is non-coercive. That is, for our offer of redemption to be aligned with God’s intention, the invitation to be recon- ciled to God must be freely offered and freely received. (See Table 3 for a comparison of how three-dimensional hospitality tips the church’s witness away from transactional witness to transformational witness.)

When Jesus sent out the 70 in Luke 10, he restricted them from taking any resources that would keep them from being reliant on the hospitality of the stranger. When the disciples returned from this journey, their report reflected transformational witness. “Lord, in your name, even the demons submitted to us!” (v. 17). Given this understanding of three- dimensional hospitality, this report of transformational witness results in the only place in the Bible where Jesus is full of joy in the Holy Spirit and prays to God—a Trinitarian exchange!

Table 3: Transformational Versus Transactional Witness

| Transactional Witness

|

Transformational Witness

|

|

|

Commitment #3: Welcoming Fresh Expressions of the New Humanity Rather Than Settling for Like-mindedness

We live in a time of great change in the way people join congregations. Never before has church affiliation been more prone to like-mindedness. While many churches in the past emerged within cloistered ethnic groups—Swiss or Russian or for that matter, Hmong Mennonites, Irish Catholics, Swedish Lutherans, etc.—these groups, while sharing a common ethnic heritage, were not necessarily “like-minded,” as evidenced by all the splintering that happened among them.

Today the situation is different. We see the phenomenon of church- shopping and church-hopping. As we’ve seen in the distinctive and engaged permutations, people are looking for a church where they “feel at home,” where their “needs are met,” where they can get something to help them live the life they’ve chosen. In a MySpace culture, community is increasingly virtual. When building virtual community becomes our primary model for building community, we no longer practice the skills required to build relationships with those near to us, we invest only in relationships with those who hold thoughts akin to us.

Church affiliation is increasingly determined by seeking a like-minded community. This is seen in mega-churches that end up red or blue where political agenda is concerned. This is seen in small emergent churches where people gather to create something new while striving to reject all institutional forms of church. Seeker-sensitive churches attempting to welcome everyone either attempt to be “traditionless” or simply don’t do ethics; it’s just about doctrine. This tendency highlights a tension for the mission-focused church. When like-mindedness becomes a defining value in how we build community, we tend to see the church as a vendor of services where the church becomes the steward and purveyor of the social values we prefer to have dominant, the social values that surround us.

On the contrary, the mission-focused church believes that the purpose of the church is to prepare us for the life that is to come. In their book, Worship and Mission after Christendom, Alan and Eleanor Kreider (2001) do a careful study of the early church in mission as a model for the post- Christendom church in mission. The Kreiders propose that the alterna- tive to seeker-sensitive churches is question-posing churches. The church will look like the kingdom, not the world, and that will cause people to pose questions to the church. Who are these people? Why do they make the choices they make? Where are they headed? What would it mean for me to join them? Only churches that are distinctive and engaged will be question-posing churches.

As alluded to in the opening story, the members of Missio Dei in Minneapolis noticed an abandoned lot in the neighborhood that was a gathering spot for a few people on Saturday evenings. After being welcomed by those who gathered at this vacant lot for a period of time, the members of Missio Dei started bringing outdoor cooking equipment and making a meal from scratch at the vacant lot. Anyone can help, all are assumed to be friends. They serve the meal in crockery bowls and real silverware rather than paper products because then people won’t get their food and walk away. Instead, they stay and fellowship as friends. Musicians perform during these evenings and people from several cultures share in this meal which begins with a prayer of thanks to Jesus.

This becomes a question-posing gathering of people. When the Republican National Convention was being held nearby, Homeland Security officers questioned them, suspicious that they may be plotting some kind of terrorist attack during the convention. So the folks of Missio Dei served up plates of food to them and invited them to join in the fellowship—and they did. Somalis, Anglos, Hispanics, young, old, wealthy, poor, refugees, homeless people, and government officials were all at a table of peace. Where else in all the world is that happening except where the kingdom has come near? One can imagine Jesus full of joy in the Holy Spirit, praying to the Father, when He looks on this scene.

What is needed if the church is to keep mission at the center of her being and purpose is to seek fresh expressions of the new humanity rather than building groups of like-minded people. The church in mission is not cloning ideology. The church in mission, through creative witness, is “worldcreating.” The church no longer thinks of “our space” but is constantly creating “new space.”

Creating new space inhabited by a new humanity was at the root of the controversy at the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15). Jerusalem was not prepared when the report came back of the conversion and baptism of Gentiles such as Cornelius (Acts 11:1-18) or the missionary impact rising out of Antioch in the commissioning of Paul and Barnabas (Acts 13:1-3). Suddenly the church was faced with a new wave of Gentile converts in Cyprus (Acts 13:4-12), Antioch of Pisidia (Acts 13:13-51), Iconium (Acts 14:1-8), and Lystra and Derbe (Acts 14:8-28). Jewish Christians in Jerusalem were prepared to receive non-Jewish converts; the Jewish faith has a long history of welcoming proselytes into their religious community. However, they were not prepared to welcome converts who, in fact, disregarded the fundamental sign of belonging to the community, the tradition of circumcision (Acts 15:1-21). The Jerusalem community was willing to welcome new Christians into their space so long as the space remained “Jewish” Christian. In order for Jews and Gentiles to merge into a single body, the church needed to practice reciprocating hospitality that created a new space. So the question in focus became, “How will including the uncircumcised Gentiles change ‘our space’ but ensure we remain the body of Christ?”

Church Planting as a Theological Task

These three commitments, trusting in narrative-based ways of knowing, receiving the hospitality of the stranger as the first movement in mission, and seeking fresh expressions of the new humanity, are essential to keeping mission central to the church’s being and purpose. But claiming these commitments “by fiat” will not make them resident in the congregation in a vital way.

Churches who keep mission at the center of their story will see mission as primarily a theological task. All must be working at the issue of how to incarnate the Gospel in culturally relevant ways while simultaneously working to incarnate the Gospel in ways that will challenge the context in which the new church is emerging. This is fundamentally a task of theological and spiritual discernment. Speaking of one of his lay leaders, a highly skilled church planter said, “People wouldn’t think he’s not a seminary student and even though he’s not gone to college or gotten any formal training of any sort, here he’s been saturated.” In order to keep mission

At the center of church life, leaders need to equip their congregations to see the world theologically. Otherwise, church growth devolves into mere marketing. Church planters know that doing theology is not something that can be relegated primarily to the realm of the academy. It is basic to the vitality of the church in mission. Some of the most sophisticated theology is created in the living rooms of regular people’s homes when they sit down and read the Bible together with their context in view and dream.

But in order to keep the three commitments vital one must do more than regurgitate theological propositions. In order to keep mission at the center of the church’s being and purpose, the church must be a primary center for leadership development. In order for mission to remain at the center of the church’s being and purpose, leaders must be developed who not only absorb the church’s narrative, but can propagate it in word and deed. Practicing theological discernment and leadership development is “world-creating.”

Seeing the congregation as a primary center for theological reflection and developing missional leaders who not only absorb the community’s story but can propagate the story, the church is continually renewed in narrative ways of knowing. This will result in Triune witness that will yield fresh expressions of the new humanity created in Christ Jesus to be good news in the world of sin, brokenness and alienation, a world wait- ing in hope for redemption.

References

- Barrett, L. (2004). Treasure in clay jars: Patterns in missional faithfulness.

Grnd Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. - Barrett, L. (2006). Authentic witness, authentic evangelism, authentic church. In J. Krabill, W. Sawatsky, & C. Van Engen (Eds.), Evangelical, ecumenical, and Anabaptist missiologies in conversation: Essays in honor of Wilbert R. Shenk (pp. 177-183). Maryknoll, NY: Orbis.

- Bosch, D. (1991/2011). Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission

(20th Anniversary ed.). Maryknoll, NY: Orbis. - Boshart, D. (2010). Becoming missional: Denominations and new church development in complex social contexts. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

- Guder, D. (Ed.). (1998). Missional church: A vision for the sending of the church in North America. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Guder, D. (2007). Missional hermeneutics: The missional authority of Scripture: Interpreting Scripture as missional formation. Mission Focus: Annual Review, 15, 106-121, 125-141.

- Huebner, H. (2005). Echoes of the word: Theological ethics as rhetorical practice. Kitchener, Ontario, Canada: Pandora.

- Keifert, P. (1992). Welcoming the stranger: A public theology for worship and evangelism. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress.

- Keifert, P. (2007). We are here now: A new missional era. Eagle, ID: Allelon.

- Kreider, A., & Kreider, E. (2011). Worship and mission after Christendom. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press.

- Kreider, A., Kreider, E., & Widjaja, P. (2005). A culture of peace: God’s vision for the church. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

- Kroll, P. (2008). Karl Barth: “Prophet” to the church. Retrieved from http://www.gci.org/history/barth

- Lamott, A. (2009). Imperfect birds. New York, NY: Riverhead.

- Lebo, L. (2001). Identity or mission: Which will guide the Brethren in Christ into the twenty-first century? (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Asbury Theological Seminary, Wilmore, KY.

- McPhee, A. (2001). The Missio Dei and the transformation of the church. Vision: A Journal for Church and Theology, 2(2), 6-12.

- Murray, S. (2000). Church planting: Laying foundations. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press.

- Van Gelder, C. (2005). Rethinking denominations and denominationalism in light of the missional ecclesiology. Word and World, 25(1), 23-33.

- Walls, A. (1996). The missionary movement in Christian history. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis.

- Wickeri, P. (2004). Mission from the margins: The Missio Dei in the crisis of world Christianity. International Review of Mission, 93(369), 182-198.

- Yoder, J. H. (2001). To hear the word. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

David W. Boshart, Ph.D., is the Executive Conference Minister of the Central Plains Mennonite Conference in Kalona, Iowa. He is the author of Becoming missional: Denominations and new church development in complex social contexts. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2010.