Introduction

All I wanted to be when I grew up was a photographer! I wanted to travel the world, creating images depicting the faces and places of real people doing real things in mighty ways. I wanted to master the craft of photography so that the images I created would grip the viewer with emotion and awe.

So I studied many photographers, both living and dead. I analyzed photographs that were considered the best-of-the-best and the worst-of-the-worst. I studied photographers who were “known” and unknown. I wanted to know what they knew. I wanted to do what they did.

I learned many things in that quest. I learned that the photographers who captured unforgettable images all had some things in common: they seemed to know themselves and people; they had vision, passion, and timing; they had an innate ability to communicate effectively; they took risks, and they learned from their mistakes. I also came to realize that as a result of their unique presence—and often their sacrifice—they made a significant and lasting contribution to our world.

Now, having become a student of leadership, I see that photography is a good teacher of leadership (Sincevich, 2007). The metaphor of photography to describe leadership can be used to challenge leaders to assess whether they are creating memorable photographs or taking casual snapshots (Brown, 2009). And as for the common traits that I discovered in the great photographers that I studied—I have also learned that those same traits are key to good leadership. So here are six lessons I learned from leadership and photography.

Lesson #1: Know Yourself and People

Ansel Adams, easily the most recognized name in photography, said, “You don’t make a photograph just with a camera. You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, the people you have loved” (goodreads.com, n.d.) The camera, no matter the price tag, fancy features, or lens attachments, is not what makes a masterful photograph. The photographer, the person, is the only one who is able to create a good photograph from ordinary tools, such as a camera and lens.

Edward Steichen (1879-1973), another legendary American photographer, observed that no photographer is as good as the simplest camera. What Steichen was saying is that you put a simple camera in the hands of a good photographer, and you will get a good photograph. Steichen also spoke out on the art form of photography as man’s explanation to himself:

Photography records the gamut of feelings written on the human face, the beauty of the earth and skies that man has inherited, and the wealth and confusion man has created . . . . the mission of photography is to explain man to man and each man to himself. And that is no mean function. Man is the most complicated thing on earth and also as naive as a tender plant. (Edward Steichen, 2004, p. 1)

The photograph of a man standing by a stone wall represents a common style used by Steichen: simple, straightforward, intense, and expressive. critics called his photographs ultra expressionistic and artistic, producing a new style of portraiture for magazines (Edward Steichen, 2004). His bold pursuit of interpreting people and his confidence in his eye as an artist influenced later generations (Edward Steichen, 2015).

The formula for strong leadership is the same as that for strong photography; it involves the person as the leader, the ability of the leader to understand how to work with others, and the results of the person’s leadership (Daniels & Daniels, 2006). Respected leaders know who they are as it relates to their beliefs and character. They know what they know as it relates to tasks and human nature, and they know what to do to provide direction and motivation (U.S. Army, 1983).

From Thomas Edison to Mary Kay to Steve Jobs, unforgettable leaders know how to tap into their uniqueness, to become world changers. According to Davis (2013), “truly great leaders know themselves well. They understand their dreams, aspirations and what motivates them to succeed, and this knowledge allows them to lead well and inspire others to succeed” (p. 1).

This ability to influence comes from the leader’s personality, traits, and abilities to make a change through her own example. The leader serves as a role model for others, she inspires and motivates to higher levels of morality, she demonstrates genuine concern for the needs and feelings of others, and she challenges others to higher levels of performance using their own innovation and creativity (Burns, 2003).

Fundamentally, this ability to know ourselves in order to know people comes from how we were created and from what we have been commissioned by God to do. In Genesis 1:26, God says, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness” (KJV). God knew us before he formed us in the womb (Jer. 1:5); therefore, if we desire to know anything—about ourselves and others—we are to ask, and he will give us that wisdom (Jas. 1:5). And from our own humanity, we are to “fan into flame the gift of God, which is in you through the laying on of my hands, for God gave us a spirit not of fear but of power and love and self-control” (2 Tim. 1:7, ESV).

Lesson #2: Have a Vision

Ansel Adams (1902-1984) is known and remembered for his vision to show nature in all its majesty and simplicity. From a simple close-up of a leaf on the ground to a majestic scene of Half Dome in Yosemite, Adams had a vision to portray nature at its best. As a result, he made a significant contribution to the environmental movement. “A photograph is not an accident—it is a concept,” said Adams (PhotoQuotes.com, n.d.). It starts with a vision.

Robert Frank noted for his photographic work on American society, says, “there is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment. This kind of photography is realism. But realism is not enough— there has to be vision, and the two together can make a good photograph” (BrainyQuote, n.d.).

A leader’s vision is often the galvanizing force that unites and motivates a diverse group of people in one direction. Focused energy in one direction, the direction of the unified vision, often leads to higher performance in the organization (Senge, 2006). For a leader, having a vision—a concept—is also about having the capacity to translate that vision into reality (Bennis, 2003). And according to a study by the hay group, employees look to leaders whom they can trust and who can communicate a vision of where the organization needs to go (Lamb & McKee, 2004).

Ansel Adams is known for his photographs of National Parks and his vision for protecting the environment. This close-up of leaves from Glacier National Park in Montana is an example of having a vision of a simple magic moment. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Photographs_by_Ansel_Adams#/media/File:Ansel_ Adams_-_National_Archives_79-AA-E23_levels_adj.jpg

This goes along with what George Washington Carver once said: “Where there is no vision, there is no hope” (BrainyQuote, n.d.). What is the vision the Christian leader is portraying? What does he hope for his organization, his people? What will be the result of his leadership?

Lesson #3: Master the Art of Perfect Timing

The need to master the art of perfect timing is critical in both photography and leadership. A good photographer is the only one who knows just when to trip the shutter at that magical moment—the moment that separates snapshots from memorable images.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, who coined the phrase “the decisive moment,” once said the following:

To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event. There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative. Oops! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever. (Zhang, 2012, p. 1)

Further, Cartier-Bresson also said that “to take photographs means to recognize—simultaneously and within a fraction of a second—both the fact itself and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that give it meaning. It is putting one’s head, one’s eye and one’s heart on the same axis” (BrainyQuote, n.d.).

White House photographer Cecil Stoughton was with John F. Kennedy when he was assassinated on November 22, 1963. Stoughton traveled back to Washington, Dc, with Lyndon B. Johnson and Jackie Kennedy on Air Force One, where he photographed the swearing in of the new president. Stoughton was the only photographer on board Air Force One. In spite of having to swiftly reload film, and then, to his horror, dealing with a jammed shutter, he was able to obtain 20 shots of the swearing-in ceremony. The one that received iconic status and was relayed around the world was the image that showed the line-up inside the crowded cabin, cropped to cut out the bloodstains still showing on Jackie Kennedy’s skirt and stockings (Simkin, 2014). No matter his challenges or the situation, Stoughton had mastered the art of perfect timing.

Just as capturing a photograph at just the right time is about aligning the head, the heart, and the eyes on the same axis, timing in leadership is about knowing when to act, managing the timing risk, discovering that timing matters, and choosing the right sequence of events (Albert, 2013).

Cecil Stoughton, a White House photographer, is known for photographing Lyndon B. Johnson being sworn in as president after John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Photographs_by_Cecil_W._Stoughton#/ media/File:LBJ_taking_the_ oath_of_office.jpg

In his book, When: The Art of Perfect Timing, author Stuart Albert (2013) says that by using the right tools we can become better at managing and deciding issues of timing. The way we describe our world often omits the facts we need to make timely decisions. We fail to include such things as sequence, rates, intervals, lags, overlaps, and other time-related elements. these elements are the structure of everything that happens and every plan that is implemented. in Albert’s (2013) words:

Everything that happens in the world happens in a particular order, takes a certain amount of time, begins or ends at a specific moment, and so on. When these characteristics are left unspecified, we can easily miss or misread what is going on. (p. 4)

Leadership is complex because it is based on relationships with people. how can one know the perfect time to speak, to act, to support, to lead? One can’t! But when we recognize our need and ask God for wisdom, we can be confident that he will provide it (Jas.1:5).

Lesson #4: Communicate Effectively

Fundamental to photography and leadership is possessing an innate ability to communicate effectively and with authenticity.

Photographers, through their photographs, engage themselves in a relationship between themselves, the subject, and the viewer. The photographer is the one who interacts with the subject through verbal and nonverbal communication, and the image that is created interacts, or communicates, with the viewer.

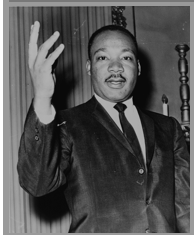

Dick DeMarsico captured a well-known photograph of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who is known around the world as the greatest civil rights leader and communicator. Dr. King influenced presidents, the media, society, education, and the way we view equality. He was an incredible leader who was able to communicate his vision for a more equitable America. His “I have a dream” speech is memorable because he painted a picture of how things could be.

Effective communication, for both the photographer and the leader, builds trust and confidence, explains the strategy, creates understanding, and makes links between the end result and the contribution of each person (Lamb & McKee, 2004).

Dick DeMarsico is known for his photograph of Martin Luther King, Jr., giving a speech. King was known for using persuasive reason in his communication. Public domain image from the Library of Congress. http:// www.loc.gov/pictures/related/?fi= name&q=DeMarsico%2C%20Dick

Successful leaders and photographers know how to communicate in order to improve the process that is needed most. They inspire a shared vision in words that can be understood by the followers. They enable others to act with the tools and methods to solve the problem. They get their hands dirty by modeling the way when the process gets tough. They encourage the hearts of their followers while keeping their pains within their own hearts (Kouzes & Posner, 1987).

Lesson #5: Take Risks!

Risk-taking is a critical element of leadership and photography. For the leader, taking risks and being comfortable with taking risks is very important in determining a leader’s effectiveness (O’Brien, 2000). For the photographer, risk-taking is just as important, because it means either getting close to get the shot or missing it completely.

Risk can be thought of as either static or possibility (Byrd, 1974). In terms of static, risk could mean losses, hazards, or danger. In terms of possibility, risk could mean innovation, creativity, growth, and success. Risk tends to be polarized in this fashion as either something to be avoided or something to be sought. The kind of risk we are talking about here is risk that leads to possibility.

Hungarian photographer Robert Capa (1913-1954) is known for his war-time photos and for being in the trenches with soldiers. He overcame fear and took many risks—risks that he sought in order to contribute to the greater good of society. He is noted as saying that “if your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough” (BrainyQuote, n.d.). With getting close comes risk.

He died on May 25, 1954, when he stepped on a landmine while on assignment in Indo-China. He had covered five wars: the Spanish Civil War, the Second Sino-Japanese War, World War II (across Europe, including the Battle of Normandy on Omaha Beach), the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and the First Indochina War. He left a legacy of over 70,000 negatives and prints.

Joe Rosenthal is another war-time photographer who took risks. One of the most memorable photographs that he captured is the one taken at Iwo Jima. Rosenthal says this about his photography of the U.S. Marines raising the American flag on Mt. Suribachi, Iwo Jima:

I swung my camera around and held it until I could guess that this was the peak of the action, and shot. I couldn’t positively say I had the picture. It’s something like shooting a football play; you don’t brag until it’s developed. (Frank, 1991, p. 1)

Joe Rosenthal is known for his photograph of U.S. Marines raising the American flag on Mt. Suribachi, Iwo Jima. Public domain image from the National Archives. http://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww2/photos/images/thumbnails/index.html

Mr. Rosenthal took many risks that day, not only for his life but also in capturing this moment in time. When he shot the picture, he didn’t even know he had the picture until weeks later when he heard on the radio that a famous photo had come from the front lines of a flag being raised by Marines at Iwo Jima.

Rosenthal and Capa took risks as photographers; taking risks even took the life of one of them. Possessing the ability to take appropriate, calculated risk is a leadership competency that is commonly included in literature (Bennis, 2003; Byrd, 1974; Kouzes & Posner, 1987). Taking appropriate risk is the ability to engage in a plan where the outcome is uncertain, but the leader strongly believes that the result will be beneficial and successful.

The phrases “Learn to take risks,” “Fail early, and often,” and “if you don’t risk big, you can’t win big” are popular sound bites of business advice (Zetlin, 2015, p. 1). So when pondering a risky move, Don Kurz, CEO of the advertising agency Omelet, suggests that any risk must serve the company’s mission, it should not be reckless, and it should not be entered into just to be fashionable. He also advises that as much as it is acceptable to have a risk-friendly attitude, it’s also acceptable to not take risks; however, with either a risk-taking or risk-averse attitude comes tradeoffs. Either way, good leaders manage the short-term and long-term benefits, as well as budgeting the financial and human capital to achieve the company’s goals and mission (Zetlin).

What does this mean for Christian leaders? Ultimately, the great commission to go into all the world and preach the gospel is our foremost goal and mission. Will it require risks? Absolutely!

Lesson #6: Learn From Your Mistakes

Learning from mistakes is a key lesson for both the photographer and leader. if what Oscar Wilde said is true—“Experience is simply the name we give our mistakes” (BrainyQuote, n.d.)—then learning from our mistakes can build strength and wisdom through experience.

Henri Cartier-Bresson comments on photography failures that are just a part of the craft: “Your first 10,000 photographs are your worst” (goodreads.com, n.d.). So the question is, what did Cartier-Bresson do with those first 10,000 photographs? Did he learn from them? Did he figure the worst parts, in order to transform them into masterpieces?

“Without question, every person makes mistakes,” and when we discover it, the best thing to do is admit it and move on (Stevens, 2011, para. 1). Leaders don’t seek mistakes, yet mistakes offer a gift of rising above the challenge and possibly reinventing themselves or their organizations. Stevens puts it this way:

True leaders take responsibility and build confidence and trust instead of blaming fate, the economy, politics, customers, shippers, taxes, etc. they control what they can control and cope with the rest. Leaders seem to know or learn that a sense of control over our situations defines one of the most basic human needs. When we feel in control of a situation, we feel empowered and focused. When we don’t, we get discouraged, and in the worst-case scenarios, we start to feel like victims or aggressors. (Para. 2)

As Bill Gates has said, “It’s fine to celebrate success but it is more important to heed the lessons of failure” (BrainyQuote, n.d.). And Elisabeth Kublerross reminds us that “the most beautiful people . . . are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of those depths” (BrainyQuote, n.d.).

Stevens (2011) leaves us with the reminder that “when you acknowledge mistakes and use them as learning lessons you create a more collaborative learning organization as well as community of transparency so not only present but future leaders can learn from [those mistakes]” (Para. 6).

Reflecting on My Photographic and Leadership Journey

I have come to realize that anyone with a camera can take a snapshot; likewise, anyone with a title can assume a leadership role. But the photographer or leader who stands out—the one who makes a real difference or makes a lasting contribution to our world—is the one who knows herself and people has a vision, understands timing, possesses an innate ability to communicate effectively, takes risks, and has learned from her mistakes.

Of all the tens of thousands of photographs that I have captured since I started taking photos at the age of 12, one of my favorite is of a young boy in Haiti because it reflects what I saw that day. I am moved with emotion every time I see it because it pulls together who I am, my vision, timing, communication, risk-taking, and everything that I have learned from my mistakes.

I was at an orphanage with a volunteer mission group of university students. I was looking for how to describe through photography a sense of place and a feeling from the kids for being in an orphanage in Haiti. I knew that I needed to gain the kids’ trust before I could photograph them one on one. I also knew that I wanted to intentionally create images that were real, not contrived or clichéd. After being there for several hours, I noticed this boy standing by a wall, and he was just looking at me. It was clear that he was trying to engage with me. I got down on his level and, through hand gestures, I asked him if I could photograph him. He responded positively, but without a smile or very much movement. I was moved by his look, both serious and yet at ease.

Brenda Boyd, Ph.D., has learned life and leadership lessons from photography since the age of 12. Photograph is used by permission of the author.

I had learned from previous mistakes that when you are in the moment, you don’t try to pose or script a photograph. You just let the situation be real, get close, get it done fast, be smooth, and already have the technical issues handled in your head and camera before moving in to create the image. So that’s what I did. I created four shots, each with a slightly different composition. It wasn’t until I got home and really looked at the photographs that I saw that the feeling I was hoping to create really did come through in the photograph. I have never been more satisfied with a photograph than this one. I risked asking permission and I risked getting close. And I overcame my shyness to engage with the boy and get personal. When I showed him the photograph, he smiled.

Legendary photographer Alfred Stieglitz once said, “Wherever there is light, one can photograph” (BrainyQuote, n.d.). I would like to propose that where there is leadership, there is light. I believe my leadership journey has brought new light to my path, and my desire is to bring light to others. God is the source of all light. As he said in John 8:12, “I am the light of the world.” And when we, as leaders, walk with God, we are also assured in this passage that we will never walk in darkness but will “have the light of life.” As Christian leaders following in God’s footsteps, our essence will shed light and love in order to make this world a better place.

In my journey as a photographer and a leader, I have learned that great leaders, like great photographers, don’t need to be legendary or world-renowned to bring a benefit to their surroundings. They just need to show up and do what they do well. in my quest to be a great photographer, I am comforted to hear that great photographers are not “remembered for the hundreds or thousands of photos they have taken and even published. They are remembered for the two or three photos that made a difference to photography or their subject” (Meyer, 2012, p. 1). In essence, leaders and photographers are about the same thing—bringing themselves and their skills to their life in order to bring meaning to the world around them.

References

- Albert, S. (2013). When: The art of perfect timing. San Francisco, CA: Wiley. Bennis, W. (2003). On becoming a leader. cambridge, MA: Perseus. BrainyQuote. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.brainyquote.com/

- Brown, E. (2009). Leadership lessons learned from photography. Retrieved from http://ericbrown.com/leadership-lessons-learned-from-photography.htm

- Burns, J. (2003). Transforming leadership. New York, NY: Grove Press.

- Byrd, R. E. (1974). A guide to personal risk-taking. New York, NY: AMACOM.

- Daniels, A., & Daniels, J. (2006). Measure of a leader: The legendary leadership formula for producing exceptional performers and outstanding results. San Francisco, CA: Mcgraw-hill.

- Davis, J. (2013). What the best leaders understand about themselves. retrieved from https://www.americanexpress.com/us/small-business/openforum/articles/what-the-best- leaders-understand-about-themselves/

- Edward Steichen. (2004). In Encyclopedia of world biography. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1g2-3404706117.html

- Edward Steichen. (2015). In The New York Times. retrieved from http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/people/s/edward_steichen/index.html

- Frank, B. M. (1991, November 16). The man who took the picture on Iwo Jima. The New York Times. retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1991/11/16/opinion/l-the-man-who-took-the- picture-on-iwo-jima-213391.htmlgoodreads.com. (n.d.). retrieved from http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/266224-your-first-10-000-photographs-are-your-worst

- Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1987). The leadership challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Lamb, L. F., & McKee, K. B. (2004). Applied public relations: Cases in stakeholder management. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Meyer, T. (2012). Transformational leadership: Lessons from great photography. retrieved from www.leadershipsa.com/Articles.html

- O’Brien, V. (2000). Flexing your risk muscles. retrieved from http://www.columbiaconsult.com/ pubs/v1_aug99.html

- PhotoQuotes.com. (n.d.). Ansel Adams. retrieved from http://www.photoquotes.com/ showquotes.aspx?id=10

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Simkin, J. (2014). Cecil Stoughton. retrieved from http://spartacus-educational.com/JFKstoughtonc.htm

- Sincevich, M. (2007). The leadership lens: Key lessons from behind the camera about leading in an uncertain future. Bethesda, MD: Staash Press.

- Stevens, D. (2011). Why good leaders learn from their mistakes. Retrieved from https:// au.drakeintl.com/hr-news/hr-articles-publications/why-good-leaders-learn-from-their- mistakes.aspx

- U.S. Army. (1983). Military leadership. Field Manual 22-100. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Zetlin, M. (2015). 5 things the smartest leaders know about risk-taking. Retrieved from http://www.inc.com/minda-zetlin/5-things-the-smartest-leaders-know-about-risk-taking.html

- Zhang, M. (2012). Henri Cartier-Bresson on “The Decisive Moment.” retrieved from http://petapix-el.com/2012/03/20/henri-cartier-bresson-on-the-decisive-moment/

- Edward Steichen (1879-1973) was an American photographer who spoke out on the art form of photography as man’s explanation to himself. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_Steichen Brancusi.jpg

Brenda L. Boyd, Ph.D., R. T. (R)(M), is Assistant Professor and Program Director for the A.S. in Medical radiography at Loma Linda University in California.