Abstract: This paper analyzes the dynamics arising from interactions between typical elements of organizational culture such as leadership, strategic processes, and knowledge management. More specifically, it seeks to establish possible relationships between leadership based on spirituality and the processes of creating, sharing, and reusing knowledge. The goal of this analysis is to establish a link between spiritual leadership as a strategy of the study of spirituality in the workplace and knowledge management.

The research is focused on the application of Louis Fry’s theory of spiritual leadership to a group of organizations made up of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) located in Medellin, Colombia. Owing to the fact that the study’s interests are aimed at comprehending human actions in an organizational context, the ethnographic method, direct observation, and in-depth interviews were used as techniques for data collection.

The most important findings of the research indicate that spiritual leadership fosters knowledge processes of the company being studied as it lays down an organizational culture that binds both beliefs and individual and corporate interests. This culture, based on spiritual values, promotes an organizational environment in which employees perceive that their spiritual needs are being satisfied and as a consequence, develop the required motivation to carry out actions and processes, including knowledge processes directed at the achievement of organizational goals.

In addition, it was found in this particular case that the Adventist religion provides a set of beliefs which, when put into practice, strengthens leadership and the ability to influence others. Finally, it was noticed that even though there are potential benefits provided by spiritual leadership to the company’s knowledge management processes, its impact is limited because the company which was analyzed is unaware of the importance of these processes and the way to manage them.

Keywords: spirituality in the workplace, spiritual leadership, knowledge management, organizational knowledge processes

Introduction

In the context of the macroeconomic and social policies promoted by today’s knowledge economy, an organization’s capacity for innovation and competitiveness is determined by its ability to manage knowledge as a strategic resource (Nonaka, 2007). Some researchers attribute the success of implementing knowledge processes to leadership styles that promote workplace environments where employees feel motivated to develop processes that contribute to effective knowledge management and to the achievement of the company’s goals (Singh, 2008; Rodríguez-Ponce, Pedraja-Rejas, & Delgado, 2010; Von Krogh, Nonaka, & Rechsteiner, 2012; Analoui, Doloriet, & Sambrook, 2013).

In this regard, Singh (2008) states that much of the success of knowledge processes is associated with leadership styles providing employees freedom to experiment and innovate, instead of those in which they feel controlled and monitored. Factors like autonomy, the ability to make decisions, the opportunity to develop their own skills, open communication, and trust create a high level of motivation and commitment to organizational goals in the staff (Analoui, Doloriert, & Sambrook, 2013).

Workplace spirituality is an emerging field of knowledge, offering perspectives and strategies based on spirituality as a source of relationship transformation. This transformation nurtures an atmosphere of satisfaction with regard to spiritual needs and provides meaning for one’s job in their lives. The success of this new field has led organizational behavior researchers to acknowledge that workplace spirituality has become one of the most influential management tools for motivating human beings (Pawar, 2008, 2009, 2014; Karakas, 2010; Birasnav, 2014).

Since knowledge processes are deeply subjective, relational, and experiential, spiritual leadership is a new perspective that can enrich traditional leadership theories. It can contribute to the management of organizational knowledge as it uses spirituality as a mechanism for cohesion of person-organization relationships. The purpose of this research is to provide empirical evidence on how the spirituality paradigm in the workplace can enrich leadership and transform it into a key tool for managing organizational knowledge processes.

This paper is structured as follows: the first section establishes the theoretical basis of the spiritual leadership model as well as the processes of organizational knowledge used in this case study. The next section presents the adopted methodology. The following section describes the implementation of the model, and the final section covers the research discussion and conclusions.

Spiritual Leadership as a Strategy for Managing Organizational Knowledge Processes

Nonaka (2007) defines a knowledge-creating company as one whose sole purpose is continuous innovation through an ongoing process of adaptation to dynamic and complex environments using the creation, dissemination, and implementation of knowledge in new products and technologies. This means that both the capacity to learn and adapt as well as the continuous creation of organizational knowledge are intangible resources that can create differentiation, competitive advantage, and ensure long-term viability.

In order to increase innovation in a knowledge-creating company, it is necessary to manage knowledge processes. This involves every action associated with the transformation of information into knowledge potentially useful in creating new products and services. As people are responsible for collecting, sharing, storing, and transforming knowledge into new products and services, these processes demand employees’ personal commitment, a sense of company ownership, and commitment to the company’s mission. Because of this, there is increased importance placed on factors like motivation and leadership in implementing strategies linked to the management of organizational knowledge.

There are numerous researchers who support the influence of leadership styles in the processes of organizational knowledge (Singh, 2008; Rodríguez-Ponce, 2010; Analoui et al., 2013; Birasnav, 2013). According to these authors, consultative and delegative leadership proposed by Hershey and Blanchard (1982), and transformational and transactional leadership proposed by Avolio and Bass (2004), help in the enhancement of knowledge processes, since they offer the employees freedom to experiment and innovate, instead of directive leadership styles in which people feel constantly controlled and monitored.

Louis Fry’s spiritual leadership theory, as an alternative proposal to traditional leadership approaches, focuses on spirituality as a tool for the creation of meaning and well-being for employees in the working environment. For this purpose, spiritual leadership proposes the creation of an inspiring vision that binds individual and organizational interests, motivates people, and leads to a spiritual well-being that translates into greater organizational commitment and productivity.

Operationally, spiritual leadership involves values, attitudes, and behaviors required to intrinsically motivate people and to generate a sense of well-being. Therefore, this perspective is considered relevant to enhancing the organizational knowledge processes, as it integrates spiritual needs with creating work environments that are conducive to the management of processes such as the creation, sharing, and reuse of knowledge.

This research is part of the theoretical field of knowledge management; thus, the review of literature is steered to search for background information documenting possible relationships between leadership and knowledge management. Special emphasis was placed on the quest for research that could evidence the bond between spiritual leadership and organizational knowledge processes. After a thorough review, it was found that even though there are quantitative studies which demonstrate the correlation between traditional leadership styles and knowledge management, there are none documenting the link between leadership models based on spirituality and organizational knowledge processes.

There are two spiritual leadership models in literature. The first is Gilbert Fairholm’s (1998) spiritual leadership model of which there is very little literature and no evidence regarding its implementation in organizations. The second is Louis Fry’s spiritual leadership model of which much research has been done resulting in empirical evidence for its implementation and replicability.

When both models were analyzed, it was concluded that Louis Fry’s spiritual leadership model was the most appropriate to be applied at the company under consideration because its theoretical and conceptual framework is consistent with the company’s practices and beliefs. This coherence between the theoretical proposal of Fry’s model and the reality observed at the company under study was considered a determining affinity criterion for the choice of model, inasmuch as it offered not only the opportunity to check its applicability in practice, but established real impact produced by spiritual practices on corporate results.

Theory of Spiritual Leadership by Louis Fry

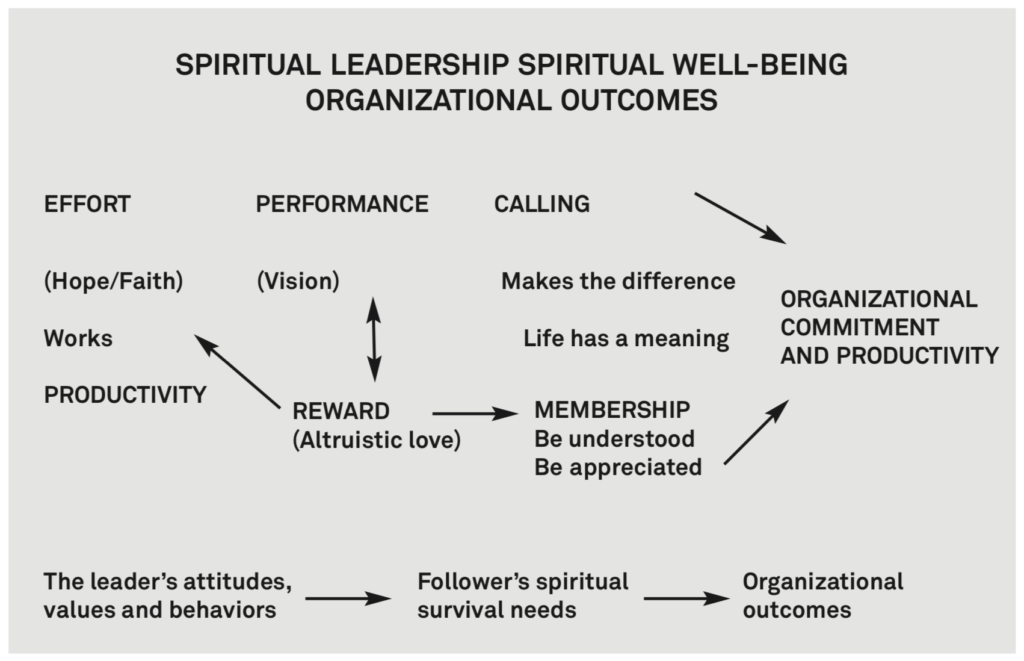

The theory of spiritual leadership defines the organization as a dynamic space of social interaction which promotes the spiritual growth of individuals by the creation of an inspiring vision and the practice of spiritual values, both of which give a special meaning to the workplace and make it a scenario of transcendence (Fry & Cohen, 2009). The theory of spiritual leadership defines itself as a causal model of intrinsic motivation based on the satisfaction of people’s spiritual needs such as calling and membership, seeking in this way to channel their potential to greater productivity, lesser absenteeism, and higher volume of business. This model divided into three interrelated stages.

The first phase is called spiritual leadership. This stage is focused on the exercise of leadership understood as premeditated actions aimed at maintaining a dynamic interaction between three categories: organizational vision, hope or faith, and altruistic love. The second stage is a consequence of the first and is called spiritual well-being. In this stage, the concrete results from leadership actions carried out during the first stage are observed, namely, the satisfaction of spiritual needs which is conducive to a sense of calling and membership in individuals, denominated by spiritual well-being. The latter maintains intrinsic motivation that drives people to work for organizational goals.

Spiritual well-being leads to the third stage called organizational and individual outcomes. In accordance with Fry, if there is spiritual well-being, organizational outcomes arrive as a natural result of an employee’s motivation and commitment. According to the model, these outcomes are evidenced through organizational commitment, productivity, financial results, etc. (Fry et al., 2011). (See Figure 1).

The following briefly discusses each of the stages that make up the spiritual leadership model, with the purpose of going into detail about the theoretical and conceptual basis proposed by the author and which is useful to contrast the empirical evidence obtained from the fieldwork.

Spiritual Leadership

According to Fry, the essence of the first stage is to fulfill spiritual needs (calling and membership) of people by means of the organization’s vision, hope or faith, and altruistic love. If these three elements are properly integrated, the successful coherence between values and practices required by spiritual leadership is achieved.

Vision: Refers to a convincing, desirable, and challenging vision of the future for the organization. Its value lies in having the inspiring potential that allows it to connect with the sense of mission of what people are and do. In this way, a collective identity arises in which a system of values is shared that fosters hope or faith at the fulfillment of the vision. Proper interaction between vision, hope or faith, and altruistic love provides a favorable environment for people to find a transcendent meaning in their work experiences (through calling and membership), and guides their attitude towards the achievement of corporate results.

Hope or faith: In the fulfillment of the vision, hope or faith is the intrinsic motivation that emerges when people have been connected to its inspiring potential. Even though there is opposition and difficulty, this motivation produces a personal commitment. People with hope or faith have a clear understanding of where they are going and how to get there; they are ready to face opposition and endure difficulties in order to reach their goals. Hope or faith provides direction and willingness to persist with the confidence that the result will bring meaning to life. Some of the qualities of hope or faith are resistance, perseverance, willingness to do what is necessary, and an open mind to expand goals and expectations of reward and victory.

Altruistic love: This is a component of organizational culture. It is the set of shared principles, values, and beliefs that are considered morally correct and build collective identity. Altruistic love is defined as the feeling of plenitude, harmony, and well-being produced as a result of coexistence in an organizational environment in which leaders and followers show real attention and esteem for each other. Altruistic love is nourished by values such as patience, kindness, forgiveness, humility, abnegation, self–control, trust, loyalty, and truthfulness.

Well-Being

Fry bases his definition of well-being on several authors. According to Fleischman (1994), Maddock and Fulton (1998), and Giancalone and Jurkiewicz (2003), spiritual well-being at the workplace is composed of two aspects: a sense of vocation or calling on a professional level, and the need for social connection or membership.

Vocation or calling: Calling refers to the transcendent experience, how the difference is made by service to others from which meaning and purpose of life are derived. People not only look for professional competence, but the feeling that their job has a social meaning or value. Pfeffer (2003), referred to in Fry (2011), mentions that people search for: a) interesting and meaningful work that allows them to learn, develop, and have a sense of competence and expertise; and b) significant employment that offers a sense of purpose. These two elements can be considered as a part of their vocation.

Membership: Membership refers to the social and cultural structures in which people find themselves, and through which they seek to be understood and appreciated. This sense of membership is achieved when people feel that they are an active part in the construction of a collective vision supported by altruistic love. This sense of belonging encourages hope or faith which motivate the member to take the necessary steps to find a transcendent vision which gives their life a sense of meaning and purpose. During that process, both leaders and followers acquire a sense of mutual care and concern in which a social connection and positive relationships with their coworkers are attained, and they are able to live a life integrated with others.

Individual and Corporate Outcomes

The enhancement of well-being produces positive results in the organization. Group members gain a positive sense of calling and membership, and become more united, loyal, and committed. Fulfilling these basic spiritual needs ensures trust, intrinsic motivation, and the necessary commitment required for people to feel encouraged to make an additional effort, more willing to cooperate, and improve performance and productivity.

In the interest of measuring “organizational commitment,” Fry proposes the measurement of affective organizational commitment developed by Allen and Meyer (1990). According to these authors, organizational commitment has three components: an affective component which refers to the emotional connection, identification, and participation in the company; a continuity component, which refers to the commitment based on the costs that employees link with leaving the organization; a normative component, which refers to the feelings of employees regarding the obligation of staying in the organization. For the sake of measuring “productivity,” Fry uses the group productivity scale developed by Nyhan (2000), which proposes to increase productivity by means of three elements: employee participation in decision making, feedback from and to employees, and employee empowerment.

The Processes of Organizational Knowledge Management

Organizational knowledge is defined as an organization’s collective body of knowledge. It is extracted from employee’s experiences, internal processes accumulated over time, and from the peculiarities of the organization as compared with its competitors (Wee & Chua, 2013). As a strategic resource, knowledge needs to be managed by the organization. However, a study conducted by Holm and Poufelt (2003) reveals that most of the SMEs do not have action plans in regard to knowledge management, and only a small percentage have formalized strategies in this area.

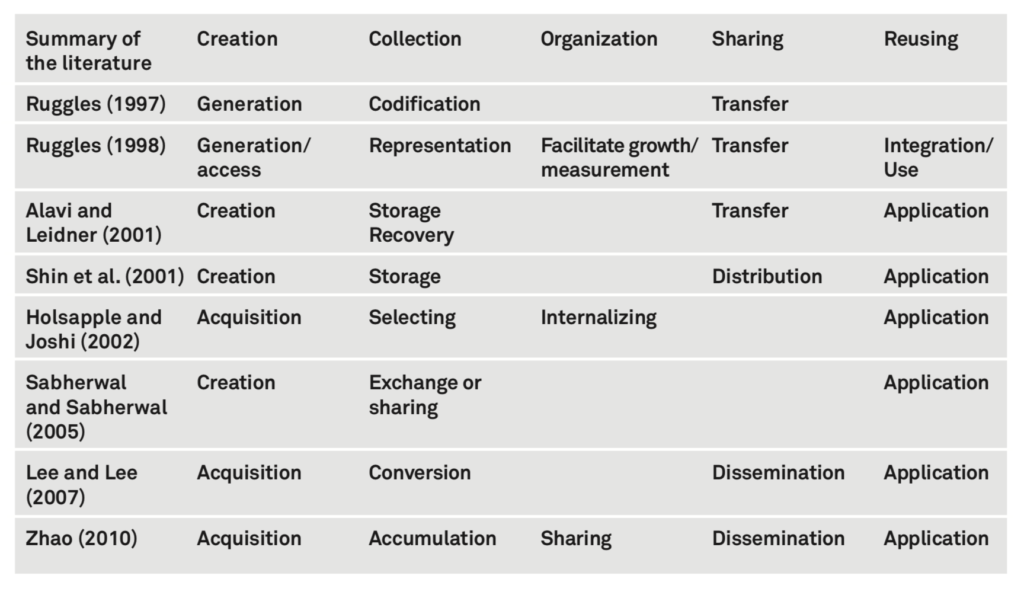

Literature records multiple approaches linked to organizational knowledge management (Wong & Aspinwall, 2004; Durst & Edwarson, 2012). Generally speaking, organizational knowledge management refers to the development of a series of processes that contribute to the use of knowledge resources or the organization’s intellectual capital. Some taxonomies linked to organizational knowledge processes are configured around the processes of creation, collection, organization, sharing, and reuse of knowledge. (See Table 1).

Some of the most-used names are: creation, generation, detection, selection, representation, organization, storage, transfer, transformation, application, integration, use, reuse, and protection of organizational knowledge.

In the literature, some of the most common definitions are:

Creation—the development of new knowledge and procedures from patterns, relations, and meanings in previous data, information and knowledge.

Compilation—the acquisition and recording of data, information, and knowledge on media.

Organization—the establishing of relationships between elements through synthesis, analysis, generalization, classification or affiliation, and creating a context in which those who need the collected knowledge can easily gain access and understanding.

Distribution—the sharing of knowledge with people who should have access to data, information, or knowledge, and blocking those who should not.

Use—the delivery of data, information, or knowledge to the tasks that create value for the organization.

Hutchinson and Quintas (2008) state that particularly in SMEs, it is very difficult to adopt a unified approach, due to the fact that knowledge processes are embedded in the formal and informal actions of an organization, and there is no clear awareness of the potential for knowledge, or of the actions that must be carried out from which it is benefited. Hence, the need to apply less prescriptive approaches that, according to the nature and distinctive features of every organization, help to understand the way companies manage their own knowledge (Alavi & Ledner, 2001).

Since in the studied organization knowledge processes happen naturally without the existence of a formal knowledge management policy, and the company is unaware of its own intellectual capital and the actions that must be taken to make the most of it, this research focuses on analyzing three interdependent processes, namely: knowledge creation, knowledge sharing, and knowledge reuse.

These processes are briefly described for the purpose of going into detail about the theoretical and conceptual basis. They are used as a reference point to contrast empirical information sources, a quick and low-cost strategy for obtaining knowledge (Egbu et al., evidence obtained from the fieldwork).

Knowledge Creation

Knowledge creation involves designing processes focused on identifying new opportunities for innovation and organizational growth (Popadiuk & Choo, 2006 cited in Wee & Chua, 2013). Especially in SME’s, limited economic resources make external information sources a quick and low-cost strategy for obtaining knowledge (Egbu et al., 2005 cited in Hutchinson and Quintas, 2008).

Knowledge creation arises as a result of sharing between subjects or by external sources that provide pertinent information for the organization. Nonaka et al. (2000) and Nonaka (2007) define knowledge creation as a process that happens by virtue of four interconnected stages: socialization (tacit to tacit), externalization (tacit to explicit), combination (explicit to explicit), and internalization (explicit to tacit).

According to preliminary studies, individual factors that encourage knowledge creation are related to positive attitude, intrinsic motivation, and the absorption capacity of the subjects (Wee & Chua, 2013). Lack of motivation, rivalry, and individualistic cultures discourage knowledge creation. Organizational factors that encourage knowledge creation are related to the existence of a research and development (R&D) department and open communication. Lack of stimulus to create new ideas, low tolerance for mistakes, and lack of policies and procedures to support new ideas are organizational factors that limit knowledge creation.

Knowledge Sharing

Knowledge sharing involves sharing tacit or explicit knowledge so that the recipient applies the acquired knowledge in new contexts (Bechina & Bommen, 2006). This process is eminently relational. Therefore, its success depends on the values, interests, and motivations of the employee (Bock et al., 2005, cited in Wee & Chua, 2013).

Environments with high levels of trust and social interaction, flat organizational structures with few hierarchical levels, decentralized cultures, high levels of communication, social activities, and low employee turnover can contribute favorably to knowledge sharing and the flow of resources (Politis, 2003; Wong & Aspinwall, 2004).

On the other hand, in highly formalized cultures (Chen & Huang, 2009), the reluctance of employees to share knowledge for fear of losing their unique value (Renzl, 2008) or their jobs (Damodaran & Olphert, 2000), lack of time to convert tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge, ignorance about what knowledge must be shared (Levy et al., 2010), fear of disclosing confidential information (Paroutis & Saleh, 2009), and lack of an organizational culture or structure that fosters knowledge sharing (Ling, 2011) limit this activity.

Knowledge Reuse

Knowledge reuse is the capture and systematization of knowledge for future use (Markus, 2001), applying it to improvements or to developments of a new product or service. Knowledge reuse involves collecting key information in order to apply that knowledge into new ideas, proposals, and initiatives that can be used to improve processes, create products, and provide services for activities that imply innovation.

Absorptive capacity and the familiarity of employees with the knowledge needs of the organization and the context in which that knowledge could be acquired, are some of the factors which contribute to knowledge reuse (Szulanski, cited in Wee & Chua, 2013). On the other hand, the lack of a knowledge-oriented culture, fragmented work environments with communication gaps, high levels of work stress with pressure to comply with goals, the lack of useful information systems for collecting and using information by all the staff, and lack of resources for research and development projects are limiting factors.

Methodology of the Study

WHOLEGRAIN is a company that produces and markets food products (bread, soy milk, cereals). It is 40 years old, has 85 employees and a portfolio of 90 products distributed throughout Colombia. It is a branch of the Inter American Health Food Company (IAHFC), a conglomerate of companies that belong to the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Latin America, and is located in Medellin, Colombia, on the campus of the Corporación Universitaria Adventista. The company has a three-level organizational structure that is composed of executive management, managerial staff (heads of processes), and operational staff (salespeople and operators in the production area). (Proposal for the operationalizing of Fry’s spiritual leadership model in WHOLEGRAIN).

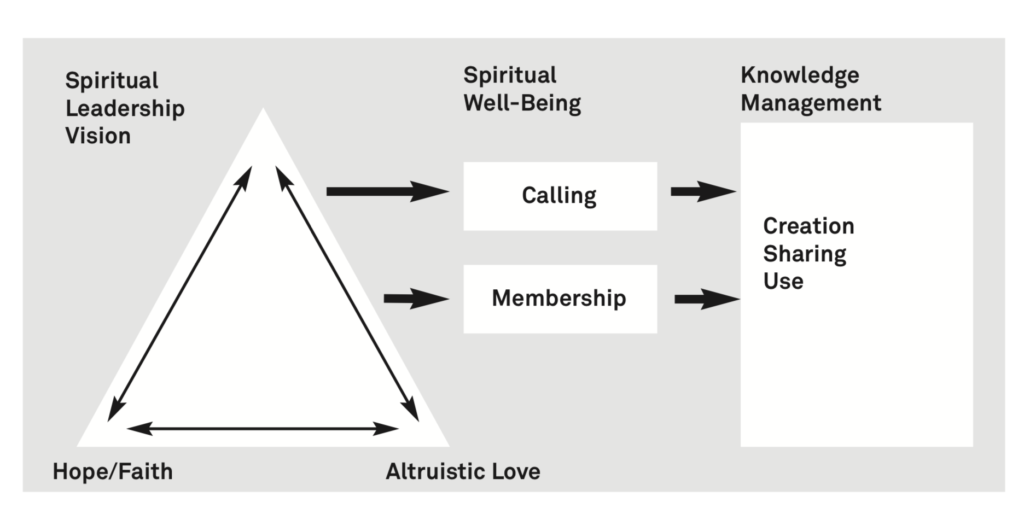

As mentioned above in the theoretical framework, Fry’s spiritual leadership theory operates by a model with three interdependent elements: spiritual leadership, well-being, and organizational outcomes. Fry states that his theory of spiritual leadership has been validated by means of its application in more than one hundred organizations. Usually, the documented studies about the application of this model use the quantitative approach and correlational method (Fry et al., 2008, 2011).

In accordance with Fry, this is a causal model in which the first stage (spiritual leadership) predicts the second stage (spiritual well-being), and this in turn predicts the third one (organizational outcomes). While reviewing empirical evidence of Fry’s research, it was found that in stage three (organizational outcomes), Fry does not limit his inquiries to “organizational commitment” and “productivity” categories, but according to the interests of each researcher, adopts new categories in which the influence of spiritual leadership and well-being could be evidenced.

Considering the interests of this research, the freedom to apply new categories for assessing organizational outcomes has been used. In this case, the original categories were superseded by the processes of knowledge creation, knowledge sharing and knowledge reuse. In this way, processes of knowledge management were integrated to the model and are not exogenous categories related to the spiritual leadership model. (See Figure 2).

Research Approach and Data Collection Process

In this research, Fry’s theoretical and conceptual structure of the model’s categories were kept. In previous studies, the author has utilized the quantitative approach and correlational method to validate his model; however, since the purposes of the current research were not to verify the correlation between variables, but to understand how they are interpreted and applied into the reality of the organization, a qualitative design was used. This created room for more in depth interviews, which allowed the researcher to compare and contrast within the theoretical model in order to better understand the organizational reality.

This study used an ethnographic method for describing organizational characteristics and human actions that are oriented by spiritual leadership and that affect processes of knowledge management. Direct observation and in-depth interviews were the techniques used to collect the information. This information, collected in interview transcripts, observation records and field notes, was coded and analyzed using the software for the treatment of qualitative data, Atlas.ti 7.0:

Ethnography disaggregates cultural objects into more specific objects, such as the characterization and interpretation of socialization patterns, the building of values, the development and expressions of cultural com- petence, the development and understanding of interaction rules, and so on. (Sandoval, 2002, p. 60)

The ethnographic fieldwork of this research implied the development of three stages carried out between January and December, 2014. The first stage involved exploring information with the CEO (two interviews) in order to promote confidence and explain the goals of the research. The interviews lasted about four hours. In the second stage, the information collected during the first interview was used to develop a semi-structured guide to compile the information that combined the categories of spiritual leadership (vision, hope or faith, altruistic love, calling, and membership) and the knowledge creation, knowledge sharing, and knowledge reuse processes.

Finally, in-depth interviews were carried out with nine informants. Each informant required three different sessions to complete the semi-structured guide resulting in about 27 sessions. Data from the interviews were systematized using the coding procedure proposed by Strauss and Corbin (2002). One informant came from the strategic level (management), seven from the managerial level (production, quality, maintenance, finance, logistics, talent management, systems), and one from the operational level (production supervisor). The criteria for the selection of the informants was their level of organizational knowledge, empowerment, and participation in administrative decision-making (members of the administrative board).

Procedures and Data Analysis

Information was validated in a process of double triangulation: a) triangulation of sources which compared data obtained from employees with institutional information (official data), and b) theoretical triangulation which focused on contrasting Fry’s model categories with categories emerging from the study.

Initially, the process of data coding consisted of examining the paragraphs of the interview transcripts, field notes and corporate reports, and classifying them into emerging subject groups. Secondly, for each subject, the categories that reflected a relationship to spiritual leadership and its implications for the processes of organizational knowledge at the studied company were identified. Thirdly, these categories were contrasted with Fry’s model and separated into two groups: those aspects predominantly associated with spiritual leadership and knowledge processes and those that were not.

Results

This study focused on operationalizing Fry’s spiritual leadership model in the WHOLEGRAIN corporation with the purpose of validating if the theory of spiritual leadership could be considered an effective strategy in the processes of organizational knowledge management. For this reason, the findings of this research are organized around the three stages comprised by the model: a) spiritual leadership, b) spiritual well-being, and c) organizational outcomes, that, in this case, correspond to the three processes of knowledge management: creation, sharing, and reuse.

Stage 1: Spiritual Leadership: Vision, Hope or Faith, Altruistic Love

In the model, the phase named “spiritual leadership” is based on the dynamic interaction between three categories: vision, hope or faith, and altruistic love. According to Fry (2003), the fact that the spiritual leader establishes an inspiring vision creates in the employees hope or faith in its fulfillment, which becomes the intrinsic motivation that inspires them to reach the vision. This dynamic between vision and people is moderated by altruistic love, namely, shared spiritual values that lead everyone to perceive a feeling of interest and appreciation for others. The spiritual leader’s role is to ensure that the interaction of these three categories lead to “spiritual well-being,” which, according to the model, is obtained by satisfying spiritual needs of calling and membership. In this section, the most important findings about the stage named “Spiritual Leadership” are presented.

Vision. During this stage of the model, it was found that most of the employees of WHOLEGRAIN associate the elements of corporate mission (mission, vision, values) with the religious beliefs promoted by the Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDAC). Additionally, WHOLEGRAIN’s mission explicitly mentions its religious vocation. This, along with a corporate culture based on Christian values, leads the staff to give a new more transcendent meaning to the vision, which increases its inspirational potential:

The Adventist Church has certain beliefs and values. For example, health is very important to us. A healthy lifestyle is not only (a matter of) education. If you are healthy, you have to prevent disease and keep your body in good health because our body is a temple of the Holy Spirit, and this is going to help you all your life. The idea is that you eat properly, eat foods as natural as possible, try to take care of your body, and exercise. So, if the company belongs to the church and there is some knowledge about healthy lifestyle, we, as a company, want to contribute to this. If God has given certain guidelines for people to live well, they must be applied. (Interview 8)

Another reason that explains the high level of staff commitment to the corporate vision is the process of how it came about. Interviews reveal that the vision arose from a collective exercise involving all the staff. According to the interviews, the WHOLEGRAIN vision has inspired employees to exert themselves in establishing a greater agreement between what they believe and what they do. This is reflected in a healthier lifestyle, better social relationships, and greater care with their use of time and money:

Trust, clarity, a very honest and clear way of doing business. People believing from the start, and always believing. People trusting us. That is worth more than any high price. I liked that the manager got authorization to add the Adventist Church logotype because that is what we are. (Interview 1)

Hope or Faith. Interviews reveal that the religious calling of the company is a predictor of hope or faith. The interviewees expressed that they felt motivated by the sense of transcendence which the religious calling lends to the corporate vision. This motivation generates a degree of commitment which exceeds the contractual sphere because it is assumed in the spiritual sphere. By participating in a transcendent vision, employees develop a sense of purpose.

Another element that strengthens hope or faith is the supernatural; the interviews revealed that employees consider the company to be a product of God’s will. Therefore, if the company fulfills its essential purpose, that is, the purpose for which the company was created, God will resolve any problem that arises. In this regard, thinking that one is a part of a company that is guided by God reinforces the trust in the fulfillment of the vision and the company’s success regardless of the circumstance:

It is a commitment. I always work thinking that what I’m doing is not done for men but for God. It generates greater responsibility, dedication, and care, and I have experienced how God has guided us. There have been many times when we didn’t have enough resources to cover all our costs and expenses, but the Lord has never abandoned us. When we least expect it, we see the solution and the miracle. (Interview 2)

Altruistic Love. It was found that WHOLEGRAIN implemented a corporate culture based on Christian values called “WHOLEGRAIN culture” since 2012. Its implementation includes choosing a new value every month. This value is socialized in work activities dedicated exclusively to reflection, collective prayer, and exchange of spiritual experiences that reinforce faith and confidence in the fulfillment of the Bible’s promises:

Every month we have a value that is everywhere: on the website, computers, walls, and everything else. Reaching people with our products, with quality, loyalty, punctuality, and honesty. These values are our philosophical underpinnings and foundation. They remind us how we should achieve the vision; they refer us to the transcendent purposes of the vision. (Interview 2)

The interviews revealed that this corporate culture based on spiritual values has made much progress towards the construction of a common ethical framework in which individual and organizational values come together. This becomes a collective identity that motivates employees to keep the structure of values with which they identify and to support consistent actions with these values:

What we seek with the principles we have in the church is to perform the vision properly. For example, I wouldn’t think of putting a product on the market that reads 480 gr., when it only weighs 460 gr. The product must be exactly what the product characteristics say it is. The influence of the church compels us to work honestly. (Interview 2)

In contrast to traditional approaches of transactional, transformational, and charismatic leadership that focus on the leader’s abilities, skills, and knowledge, Fry understands leadership as a process of social influence in which the entire team participates in holding the spiritual environment of the organization. The findings reveal that in WHOLEGRAIN there a spiritual environment exists, that is guided and supported by the CEO. In this case, what Fry (2003) postulates about the existence of a leadership environment is only partially true because, although the managerial staff provides support in their area of influence, employees do not perceive spiritual leadership as a collective process:

He (the manager) has a worship service every Monday with sales agents and does his work. The work involves promoting a value in WHOLEGRAIN every month. This month we are working on the value of prudence. It has very good subjects. People are reminded, everywhere there are posters. that part works. (Interview 1)

Who promotes the subject of spirituality, vision, and goals? Of course, the manager. Don’t you notice this from the other areas or managerial staff? No, it is all about what the manager says. (Interview 9)

Stage 2: Well-Being: Calling and Membership

According to Fry (2003), the stage defined in the model as “spiritual well-being” emerges from the satisfaction of two spiritual needs: calling and membership. Calling refers to the sense of call related to the altruistic service offered from what it is and what is done regarding helping others from what is known. Membership is related to the necessity of being part of something and feeling accepted and valued by that community. In accordance with Fry, if the company provides a proper environment for meeting the calling and membership needs, it creates a sense of purpose that strengthens intrinsic motivation and leads employees to strive to achieve organizational goals. Here are the most important findings about the “spiritual well-being.”

Calling. In WHOLEGRAIN, community service activities are meant as a chance to teach, change habits, influence, and help others. For that matter, evidence was found that employees not only participate in activities organized by the company, but some of these activities are promoted by the employees themselves as they perceive these activities as an opportunity to strengthen team unity and reinforce the practice of values such as unity, friendship, camaraderie, generosity, and service to others. These actions not only allow for a sense of calling to develop, they also contribute to creating and supporting an environment of spiritual well-being:

Service to others outside of work was an opportunity for us all to be united. Maybe the purpose of sales agents was only to go and deliver bread to street people without thinking that Adventists and non-Adventists might unite, but as others heard about this, they began to join in. Sales agents have meetings every morning. In fact, they were the first to give their own money for this activity. (interview 2)

Another aspect, according to the theory of spiritual leadership, that is part of calling is that people expect to have the possibility of finding an interesting and meaningful job that allows them to learn, develop, and have a sense of expertise and competence. It was found that some interviewed individuals feel restricted, due to fact that the company currently does not have a training program for the staff nor do they allocate resources for new projects or programs for staff training. When asked for the reasons, people said that the company was in a difficult financial situation. They appeared understanding and were prepared to postpone their expectations. However, analyzing the interviews, it becomes noticeable that in the medium term this could be a constraining factor for employee motivation as they feel that their job does not offer them the chance for learning and developing themselves professionally:

There are times when I feel stagnant because there are no resources for doing many things that I want, that issue is limiting, but, on the other hand, there are a lot of things to improve, there is always something different to do. (Interview 8)

Membership. The second element of spiritual well-being is “membership.” Inquiring about this aspect, it was found that some years ago WHOLEGRAIN was characterized by having difficult labor relations, and communication between managers, employees, and departments was tense. This damaged relations and decreased employee motivation and commitment to the company. Currently, employees state that the corporate culture based on spiritual values has allowed them to regain trust and improve relationships. The daily practice of collective prayer and meditation has helped them to draw closer to each other on a personal and family level, which has allowed them to experience positive relationships with coworkers and participate in an environment of connection and friendship.

Additionally, it was found that social service activities developed inside the work environment are a space where the bond among employees is strengthened, since these kind of activities are a source of satisfaction of spiritual needs. They channel calling by means of selfless service and assistance to others and strengthen the sense of calling by providing the opportunity for one to live a life integrated to a group. That has a transcendent purpose:

I have a lot of to do with clients since I was in the Quality Department. Now I’m in the Production Department. They still call me and ask me; they say, a lot of people are avid for knowing what to do to be healthier; that is something I like a lot. If I can do something for someone, that motivates me to teach them, explain to them about their questions. There are many that say: “I only consume WHOLEGRAIN because it is what helps my health”, those things also motivate me a lot. I’m doing something productive for humanity. (Interview 8)

Stage 3: Organizational Outcomes: Knowledge Creation, Knowledge Sharing, and Knowledge Reuse

In accordance with Fry, the stage defined as “organizational outcomes” rises up naturally as a consequence of the two previous stages. Organizational outcomes reflect the benefits that the organization obtains after implementing the initial stages. The goal of this research is to determine whether the previous stages succeeded in influencing the company’s processes of knowledge management. Here are most important findings:

Knowledge Creation. Research shows that most of the SMEs do not create knowledge, but acquire and adapt knowledge to their needs because of the scarcity of economic resources. This limitation implies negotiating the acquisition of strategic resources and services on which its own activities depend (Teece, 1988; Vangen et al., 2005; Hutchinson & Quintas, 2008). In WHOLEGRAIN, the recent projects for developing new products have relied on the procurement and adaptation of existing knowledge through purchases from or donations by allied companies.

Interviews disclose that in WHOLEGRAIN there is a favorable condition for knowledge creation, since the certainty that the company is guided by God, the commitment of employees, and low employee turnover create an environment of cooperation and generation of ideas. However, it was noted that the economic factor is the biggest limitation for the creation or acquisition of knowledge. Interviews revealed that due to the company’s precarious situation, the CEO restricts investment in research and development projects and focuses on survival. Another aspect which arose from interviews is that some staff members consider the absence of a supportive attitude toward new products initiatives as the real limitation for knowledge creation:

We recently started a new project. This project is hardly new actually, as it had been suggested to the boss, many years ago. When it was initially suggested the boss’s reply was: “Yes, that’s a great idea but let us do it sometime in the future’. It took years to get this project started. I under- stand that projects require money, but I don’t know if it is all about money, or the leadership just don’t want to do it . . . . the process of entering new products into the company is very slow. I mean, there is no culture of acceptance of new ideas, of wanting to innovate all the time. (Interview 3)

According to the interviews, the absence of a culture of innovation is reflected on a lack of budget allocation for these activities, slowness, and centralization of decisions related to new projects, a lack of technical processes accompanying the development of initiatives from their incubation to their launch, and lack of incentives to promote and reward new ideas.

Knowledge Sharing. The interviews show that one of the most important contributions of WHOLEGRAIN’s organizational culture based on its Christian values is the building of staff trust. Moments of reflection and prayer stimulate the sense of membership and strengthen relationships. They also create an environment in which spiritual values such as harmony, forgiveness, and acceptance are exercised. Good relationships among employees have achieved greater interaction, better work environment, and greater willingness to cooperate and share ideas which have made the training processes easier among former and new employees. They also fostered communication by creating safe spaces to resolve problems, to generate new ideas for improving processes, the implementation of small innovations, and enhancement of working positions through staff initiative. All of these aspects could be considered activities inherent to the processes of organizational knowledge:

Of course, when we see the same value every day, it influences all of us indirectly. Besides, it allows us to have more interaction, since we were so distant. However, a bond of trust was built, and now we are not work- mates, but friends. (Interview 5)

Knowledge Reuse. Finally, it was found that knowledge reuse is made by direct interaction among employees who, based on experience, create and modify processes in a quick and flexible way because there are no established processes for knowledge transformation from tacit to explicit. People share tacit knowledge, since the company does not have practices for collecting and transforming this information into explicit knowledge. The creation and modification of the processes are made easier due to the seniority, experience, and ability of employees who knew and understood key business processes, and solutions for improving processes of one department in relation to other departments. Aspects like familiarity among employees, experience, and low staff turnover makes employees a valuable source of tacit knowledge:

Head of the Department of Information Systems: I saw that the Payroll Department calculated a seller’s commission only at the end of the month. I talked to the heads of the Payroll Department and Sales Department so that the commission would be calculated as soon as a sale was made. This way, sales agents don’t have to wait until the end of each month to know their commission, and they can feel stimulated to sell more. (Interview 5)

In addition, it was found that in WHOLEGRAIN, technological devices such as computers were used for managing operational processes like sales, inventory, and storing historical data by departments, but not used as a mechanism for information storage for later analysis and reuse. Even though the data stored in these devices could be freely accessed, it was not used, since its relevance and usefulness was unknown.

Moreover, it was found that the employees themselves were responsible for making the decision about what kind of data was stored, how long, and with whom it was shared with. There was no a formal policy on information storage and analysis for the sake of improving processes or making decisions. That probably happened because the company is unaware of the knowledge potential such information has to it and how it to best utilize it.

We have common files on the server where I have my folder and keep everything. I have schedules, supplier lists, information about replacement parts, prices, where I can get something, how long ago it was bought. That is my information. The sales department has its own folder and information. I don’t use sales information because even though I can, I’m not going to understand anything. The same happens to them and my folder. (Interview 3)

Discussion and Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to establish the influence of spiritual leadership on knowledge processes by means of the application of the spiritual leadership model, proposed by Louis Fry, to WHOLEGRAIN, a medium-sized company. At this stage, two questions need to be considered.

First, how applicable was Fry’s spiritual leadership model to WHOLEGRAIN’s organizational reality? The results of the study indicate that the model is relevant to WHOLEGRAIN’s organizational reality. Therefore, this model can be considered as an operationalization strategy of workplace spirituality. The significance of religion in the validation of the model is one of the most important findings of this study. Fry allows organizations to feel free to choose their references on which to base their own spirituality. However, by analyzing his writings, it is possible to demonstrate the repeated use of religious concepts and texts from the Bible to explain his categories.

This connection between Fry’s model and religion highlights the theological sense underlying his model. In accordance with what was observed at the company, the spiritual leadership model points to a spiritual transformation that happens when people live a religious experience at the organizational level. In this case, the company is an organization with an obvious religious vocation, hence religion is directly and significantly linked to spirituality. Religious beliefs are the source of its principles and values, nourishing the spiritual experience of its people and of the entire organization, over which it is possible develop a successful spiritual leadership.

Osman, Gani, Hashim, and Ismail (2012) define religion as an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols designed to facilitate proximity to the sacred and transcendent, and to foster the mutual responsibility of everyone living in community. At the same time, they specify that spirituality is the personal search to find answers regarding life’s most fundamental questions.

In this case, the findings revealed that at the studied company, the spirituality and religion constructs are related, due to the fact that the Seventh-day Adventist Church provides a complete system of principles, values, and beliefs directing the SMEs’ corporate culture and influencing the channels through which spirituality was built which provided meaning to the personal and professional life of employees.

This conditioning of the spiritual to the religious has had deep implications in the behavior of individuals at the company. Since religious principles influence actions, perceptions, personal decisions, and increase the employee’s morale and productivity, these elements have an impact on organizational outcomes (Connolly & Myers, 2003; Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, 2003; McCarty, 2007; Vasconcelos, 2009).

The second question asks whether the initial stages of the model (spiritual leadership: vision, hope or faith, altruistic love and wellbeing, calling, and membership) were able to have an impact on the third, namely, organizational outcomes. This third stage is composed of the processes of creation, sharing, and reuse of knowledge. Indeed, this study showed that stages one and two of the model did create a favorable condition for the company’s processes of knowledge management. This allows for the conclusion that spiritual leadership may be considered a strategy for leading processes of organizational knowledge. However, it should be noted that the company’s poor awareness about knowledge processes was a limiting condition for managing these. The company is unaware of how to use knowledge as a strategic resource for developing new products that enhance the productivity and competitiveness of the company.

One of the favorable conditions for the processes of knowledge management turned out to be the corporate culture that brings principles and beliefs of the employees together with the company’s beliefs and religious values. This alignment unifies the collective and individual identity, and fosters a proper work environment that generates actions directed to the processes of creation, sharing, and reuse of knowledge. Many descriptive researchers have identified culture as a significant catalyst or a major obstacle to creating and sharing knowledge. A favorable organizational culture of knowledge is one of the most important conditions for achieving success in initiatives of organizational knowledge management.

Knowledge Creation

Two restricting aspects of WHOLEGRAIN’s knowledge creation were the absorptive capacity of new ideas from the market and the ability to translate them into new products. Dou and Dou (1999) state that when an SMEs’ information environment is poor, demonstrated by the company’s quality of the sources and information, managers remain isolated and innovation is scarce. This statement was confirmed by the observed reality, since it is showed that the lack of external information sources (trainings, travels, events, participation in guilds) and the restricted capacity to manage internal resources and ideas generated little creativity for knowledge creation resulting in concrete products. Cohen and Levinthal define this ability as the firm’s absorptive capacity (1990).

A second aspect considered as limiting knowledge creation is that employees do not perceive an attitude of interest and commitment from management to the knowledge processes. Researchers point out that this situation is potentially damaging to the organization, since management has a key role to resolve what kind of resources should be allocated and how long employees are allowed to carry out knowledge management activities (Singh, 2008; Durst & Edvardsson, 2012).

Knowledge Sharing

Ragab and Arisha (2013) state that organizational culture has been identified as a key determinant of knowledge of management’s success or failure. The analysis of the process of knowledge sharing in WHOLEGRAIN identified that corporate culture based on Christian values is a favorable condition for socialization, creation of collective identity, and building of trust among employees. Davenport and Prusak (1998) argued that this is achieved because culture becomes a catalyst in fostering an environment whose values encourage the employees to share, interact, communicate, cooperate, and more.

The consistency between values, rules, and practices at WHOLEGRAIN has created a collective identity that reinforces the interaction among workers, strengthens the bond with stakeholder support groups, and establishes a common ethical framework for making decisions. This finding is consistent with Hamdan and Damirchi (2011), who suggest that environments with high levels of trust and social interaction, in terms of frequency of approaches and communication, foster knowledge sharing and flow of resources.

A limiting aspect for knowledge sharing is that operational activities requiring teamwork, process improvement, and decision-making processes are affected by failures of communication. Employees argue that although management has made efforts for promoting spaces that allow interaction among departments, those are not enough, but are focused on routine issues like vacation approval, contract renewal, and more. Frustration is caused by a lack of space for discussion and attempting to solve every department’s critical problems; this weakens the interest in cooperating, creates an attitude of indifference, delays the process improvement, and discourages the sense of team.

Wee and Chua (2013) state that organizations in which there are few interactions, regular working meetings, and management discussions restrict the knowledge of functions, responsibilities, and processes among departments, and at the same time, reduce chances for management and employees to propose operational solutions and collaborative initiatives contributing to process improvement.

Knowledge Reuse

The last knowledge process that this research analyzed was knowledge reuse. This study found that the company was unaware of the importance of managing knowledge processes and has not developed deliberate actions allowing it to benefit from organizational knowledge in order to increase its competitiveness. This finding is consistent with Hutchinson and Quintas’ (2008) ideas, which indicate that SMEs tend to develop informal processes of knowledge, understood as those practices that are not labeled or constituted in terms and concepts of knowledge management.

One of the reasons associated with informality is job stability. Employees are a valuable source of tacit knowledge, obtained by years of experience. This condition makes them information providers for the control and monitoring systems of administrative management and production processes (quality management system). Notwithstanding, this strength is not being exploited by the company, since it has left this pool of tacit knowledge residing in employee expertise unused. The company doesn’t seem to understand or know how to manage the benefits provided by this transformation of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge.

Therefore, this study concludes that the influence of religion and spirituality is important in order to create a proper corporate culture for bringing together individual and organizational interests. In this regard, this research validates Fry’s theory of spiritual leadership as a conceptual tool for the practice of spirituality at the workplace. Nonetheless, at the studied company, the conditions allowing the development of strategies for the management of knowledge processes are incipient, which significantly weakens the impact of spiritual leadership.

References

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107–136.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1−18.

Analoui, B. D., Doloriert, C. H., & Sambrook, S. (2013). Leadership and KM in UK ICT organisations. Journal of Management Development, 32(1), 4-17.

Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (2004). Multifactor leadership questionnaire: Manual and sampler set, 3rd ed. Redwood City, CA: Mind Garden.

Bechina, A. A., & Bommen, T. (2006). Knowledge sharing practices: Analysis of a global Scandinavian consulting company. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 4(2), 109-116.

Birasnav, M. (2013). Knowledge management and organizational performance in the service industry: The role of transformational leadership beyond the effects of transactional leadership. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1622-1929.

Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y. G., & Lee, J. N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87-111.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthall, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152.

Connolly, K. M., & Myers, J. E. (2003). Wellness and mattering: The role of holistic factors in job satisfaction. Journal of Employment Counseling, 40(4), 152-160.

Crawford, C. B. (2005). Effects of transformational leadership and organizational position on knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(6), 6-16.

Chen, M., Huang, M. & Cheng, Y. (2009). Measuring knowledge management performance using a competitive perspective: An empirical study. Expert Systems with Applications, 36(4), 8449-8459.

Damodaran, L. & Olphert, W. (2000). Barriers and facilitators to the use of knowledge management systems. Behaviour & Information Technology, 19(6), 405-413.

Dou, H., & Dou, J. M. (1999). Innovation management technology: Experimental approach for small businesses in a deprived environment. International Journal of Innovation Management, 19(5), 401–412.

Durst, S., & Edvardsson, I. R. (2012). Knowledge management in SMEs: A literature review. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(6), 879-903.

Egbu, C. O., Hari, S., & Renukappa, S. H. (2005). Knowledge management for sustainable competitiveness in small and medium surveying practices. Structural Survey, 23(1), 7–21.

Fleischman, P. R. (1994). The healing spirit: Explorations in religion and psychotherapy. Cleveland, OH: Bonne Chance Press.

Fry, L. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14,693-727.

Fry, L. W. (2008). Spiritual leadership: State-of-the-art and future directions for theory, research, and practice. In J. Biberman & L. Tishman (Eds.), Spirituality in business: Theory, practice, and future directions (pp. 106−124). New York, NY: Palgrave.

Fry, L., & Cohen, M., (2009). Spiritual leadership as a paradigm for organizational transformation and recovery from extended work hours cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 84, 265–278.

Fry, L., Hannah, S., Noel, M., & Walumbwa, F., (2011). Impact of spiritual leadership on unit performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(2), 259-270.

Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2003). Toward a science of workplace spirituality. In R. A. Giacalone, & C. L. Jurkiewicz (Eds), Handbook of workplace spirituality and organizational performance, (pp. 181-192). New York, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Hamdam, H., & Damirchi, G. V. (2011). Managing intellectual capital of small and medium size enterprises in Iran case study: Ardabil province SMEs. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3(2), 233-240.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1982). Management of organizational behaviour. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE.

Hislop, D. (2009). Knowledge management in organizations, (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Holm, M. J., & Poulfelt, F. (2003). The anatomy of knowledge management in small and medium-sized enterprises. Paper presented at LOK Research Conference, Middelfart, 1–2 December, (Egbu, et al, 2005; Hutchinson y Quintas, 2008).

Hutchinson, V., & Quintas, P. (2008). Do SMEs do knowledge management? Or simply manage what they know? International Small Business Journal, 26(2), 131-54.

Karakas, F. (2010). Spirituality and performance in organizations: A literature review. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 89-106.

Levy, M., Hadar, I., Greenspan, S. & Hadar, E. (2010). Uncovering cultural perceptions and barriers during knowledge audit. Journal of Knowledge Management, 14(1), 114- 127.

Ling, C. T. N. (2011). Culture and trust in fostering knowledge-sharing. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(4).

Maddock, R. C., & Fulton, R. L. (1998). Motivation, emotions, and leadership: The silent side of management. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Markus, M. L. (2001). Toward a theory of knowledge reuse: Types of knowledge reuse situations and factors in reuse success. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 57-93.

McCarty, W. B. (2007). Prayer in the workplace: Risks and strategies to manage them.Business Renaissance Quarterly, 2(1), 97-105.

Nyhan, R. C. (2000). Changing the paradigm: Trust and its role in public sector organizations. American Public Review of Administration, 30, 87-109.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., & Konno, N. (2000). SECI, ba, and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Planning, 33, 5–34.

Nonaka, I. (2007). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard Business Review, 85(7/8), 162-171.

Osman-gani, A., Hashim, J., & Ismail, J. (2012). Establishing linkages between religiosity and spirituality on employee performance. Employee Relations, 35(4), 360-376.

Paroutis, S., & Saleh, A. (2009). Determinants of knowledge sharing using web 2.0 technologies. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13(4), 52-63.

Pawar, B. S. (2008). Two approaches to workplace spirituality facilitation: A comparison and implications. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29(6), 544–567.

Pawar, B. S. (2009). Workplace spirituality facilitation: A comprehensive model. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 375–386.

Pawar, B. S. (2014). Leadership spiritual behaviors toward subordinates: An empirical examination of the effects of a leader’s individual spirituality and organizational spirituality. Journal of Business Ethics, 122, 439–452.

Pfeffer, J. (2003). Business and the spirit. In R. A. Giacalone & C. L. Jurkiewicz (Eds.), Handbook of workplace spirituality and organizational performance, (pp. 29–45). New York, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Politis, J. D. (2001). The relationship of various leadership styles to knowledge management. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22(8), 354-64.

Politis, J. D. (2003). The connection between trust and knowledge management: what are its implications for team performance. Journal of Knowledge Management, 7(5), 55-66.

Popadiuk, S., & Choo, C. W. (2006). Innovation and knowledge creation: How are these concepts related? International Journal of Information Management, 26(4), 302-312.

Ragab, M., & Arisha, A. (2013). Knowledge management and measurement: A critical review. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(6).

Renzl, B. (2008). Trust in management and knowledge sharing: The mediating effects of fear and knowledge documentation. Omega, 36(2), 206-220.

Rodríguez-Ponce, E., Pedraja-Rejas, L., Delgado, M., & Rodríguez-Ponce, J. (2010). Gestión del conocimiento, liderazgo, diseño e implementación de la estrategia: Un estudio empírico en pequeñas y medianas empresas. Ingeniare. Revista Chilena de Ingeniería, 18(3), 373-382.

Sandoval Casilimas, C. A. (2002). Módulo 4. Investigación Cualitativa, en Briones, Guillermo (coord.) Programa de Especialización en Teoría, Métodos y técnicas de Investigación Social. Bogotá: ICFES.

Shin, M., Holden, T., & Schmidt, R. A. (2001). From knowledge theory to management practice: Towards an integrated approach. Information Processing and Management, 37, 335-355.

Singh, S. K. (2008). Role of leadership in knowledge management: A study. Journal of Knowledge Management, 12(5), 3-15.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2002). Bases de la investigación cualitativa: técnicas y proced- imientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Bogotá. Colombia. (2a.ed.). CON- TUS-Editorial Universidad de Antioquia.

Szulanski, G. (2003). Sticky knowledge: Barriers to knowing in the firm. London, England: SAGE.

Tsai, W., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Academy of Management Journal, 41(4), 464-476.

Vasconcelos, A. F. (2009). Intuition, prayer, and managerial decision-making processes: A religion-based framework. Management Decision, 47(6), 930-949.

Von Krogh, G., Nonaka, I., & Rechsteiner, L. (2012). Leadership in organizational knowledge creation: A review and framework. Journal of Management Studies, 49(1), 240-277.

Wee, J., & Chua, A. (2013). The peculiarities of knowledge management processes in SMEs: The case of Singapore. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17(6), 958-972.

Wong, K. Y., & Aspinwall, E. (2004). Characterizing knowledge management in the small business environment. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(3), 44-61.

Lorena Martínez Soto teaches in the School of Administrative and Accounting Sciences at the Adventist University of Colombia. She holds an MBA from the University of Montemorelos, Mexico, and a Master’s Degree in Administration Sciences from EAFIT University, Medellín, Colombia. She is a doctoral candidate in Organizational Studies at the Autonomous Metropolitan University (UAM) in Mexico City.