Abstract: A pastor with high emotional intelligence is more likely to be successful in the skills required to lead a church, which will likely produce a healthier church. Stated another way, a lack of emotional intelligence is a potential predictor of pastoral leadership failure, which could lead to an unhealthy church. Current church authors and researchers miss emotional intelligence as a key leadership competency. This article raises the importance of emotional intelligence and suggests that an emotionally intelligent pastor who is both self-aware and socially aware can relationally lead a church well.

The Hartford Institute for Religion Research (n.d.) estimates that there are currently 314,000 Protestant churches in the United States. However, over the last two decades, researchers generally report that 4,000–5,000 churches close their doors each year (Reeder, 2008; Malphurs & Penfold, 2014; Stetzer & Dotson, 2007). A Lifeway Research report of 34 denominations in the U.S. revealed that 1,200 more church closures occurred in 2019 than in 2014 and that 4,500 churches closed in 2021. The same study also showed that 3,000 churches were planted in 2019. However, this figure is 1,000 less than the total churches planted in 2014 (Earls, 2021). Given that churches are closing at a higher rate than churches are being planted, there is much work to do. In addition, within the Southern Baptist Convention, the number of people one church serves has nearly doubled in the last century, from 3,897 in 1900 to 6,139 in 2010 (The North American Mission Board, n.d.).

What could be contributing to the closures of churches? One consideration is that Americans now value religion less than they did 25 years ago. A recent poll conducted by the Wall Street Journal reported that more than 60% of Americans valued religion in 1998 but that statistic is now less than 30% (Zitner, 2023). Another consideration is the sovereignty of God. Current church authors and researchers acknowledge the importance of God’s sovereignty as a contributing factor to a church’s health. As a second priority, they then emphasize a pastor’s leadership skills as indicative of a church’s health and success (Reeder, 2008; Malphurs & Penfold, 2014; Stetzer & Dotson, 2007; Payne, 2009).

John Maxwell (2022) said, “Everything rises and falls on leadership” (p. 70). Considering church authors and researchers like Stetzer, Rainer, Malphurs, Barna, and others also emphasize the importance of leadership, it seems appropriate to study the skills and competencies of successful pastors. Spencer and Spencer (1993) define competence (or competency) “as underlying characteristic of an individual that is casually related to criterion-referenced effective and/or superior performance in a job or situation” (p. 9).

In Competence at Work, Spencer and Spencer provide validated research on competency creation, which was repeated by Joseph Hudson in 2017 with a focus on a competency model for a church revitalization pastor. Other church leadership competency researchers have utilized similar models, often based on David McClelland’s Models for Superior Performance using Behavioral Event Interviews (Spencer & Spencer, 1993). A review of church leadership competency studies that Hudson found and a search for additional studies reveal two things: (1) results often vary, and (2) little research has occurred since Hudson’s study in 2017. To find similarities between research studies of church leadership competency, further review was conducted.

In reviewing a competency study referenced by Hudson, John Thomas (1995) concluded that high-performing Cuban pastors share characteristics in personal and interpersonal competence that predict success in church leadership. Thomas’s research showed that one characteristic of personal competence is being self-aware, and one characteristic of interpersonal competence is being socially aware. Both self-awareness and social awareness are characteristics of emotional intelligence. Bradberry and Greaves (2009) describe emotional intelligence (EQ or EI) as an individual’s awareness of themselves, an awareness of themselves with others (social awareness), and their appropriateness in responding to a given situation. Hudson (2017) also referenced the importance of emotional intelligence as he reviewed a dissertation by Jared Roth, but Hudson’s final competency model excludes the term “emotional intelligence.” Though not explicitly stated, the characteristics of emotional intelligence appear in Hudson’s and other leadership competency studies as terms like “self-awareness” or descriptions like “the ability to sympathize with others.”

Emotional intelligence is not the only repeated competency, but it seems to be one of the most consistent among high-performing church leaders. Bradberry and Greaves (2009) conclude that emotional intelligence is the single most reliable predictor of an individual’s success. Because Hudson, Thomas, and others include aspects of emotional intelligence in their research, emotional intelligence is likely a key competence for pastors. Competence in emotional intelligence for pastors will likely produce a healthier, more sustainable, and multiplying church. Stated another way, a pastor’s lack of emotional intelligence is a potential predictor of failure, which could lead to an unhealthy church.

Emotional intelligence is broader than the definition of Bradberry and Greaves. In a 2004 article, Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso provide a working definition of emotional intelligence:

The capacity to reason about emotions, and of emotions to enhance thinking. It includes the abilities to accurately perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions so as to assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth. (p. 197)

Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso’s definition encapsulates four branches of emotional intelligence that they describe as (1) study of the perception of emotions and the capacity to discern emotions, (2) the ability of emotions to help thinking and planning, (3) the ability to understand emotions and their potential outcomes over time, and (4) the management of emotions toward individual goals, self-knowledge, and social awareness.

Factors important for pastoral leadership include more than competence in emotional intelligence. Malphurs and Penfold (2014) noted that not all pastors will possess every leadership skill indicative of success. Yet, emotional intelligence is likely one competence that should be recognized with high importance for all pastors. This article explores the terms associated with emotional intelligence, the competence categories for pastors, and differing church contexts. The focus will show that emotional intelligence is important to—but often unexplored by—church leaders and researchers.

Emotional Intelligence

According to Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso (2004), the term “emotional intelligence” is a new concept compared to other psychological studies. Most research on pastoral competence does not specifically reference emotional intelligence. Often, researchers identify emotional intelligence as the need for a pastor to be self-aware or personable leadership (Hudson, 2017; Oldenkamp, 2018; Thomas, 1995; Thompson, 1995; Woodruff, 2004). Conversely, research on emotional intelligence often excludes the spirituality of an individual. If included, it only acknowledges spirituality as it relates to other intelligences, not spirituality itself (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2004).

While the study of emotional intelligence is relatively new, research reveals that emotional intelligence has proven to have positive implications for academic performance, prosocial behaviors, and organizational leadership (Mayer, Salovey, &Caruso, 2004). Church authors note that pastors often operate as generalists and maintain a myriad of interpersonal relationships (Malphurs, 1998; Malphurs & Penfold, 2014; Payne, 2009; Reeder & Gragg, 2008; Thomas, 1995). Therefore, a pastor or church leader’s emotional intelligence could impact their abilities across multiple areas of ministry.

Identifying the Right Branch of Emotional Intelligence

In Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso’s (2004) four branches of emotional intelligence, they define Branch 4 as “the management of emotion, which necessarily involves the rest of personality. That is, emotions are managed in the context of the individual’s goals, self-knowledge, and social awareness” (p. 199). They further define emotional intelligence as a leaders ability to understand self in relation to others. Because pastors must manage church goals with both self-awareness and social awareness, this article will focus on observations related to Branch 4.

Similar to the definition of Branch 4, Bradberry and Greaves (2009) indicate emotional intelligence is the management of self and of others as it relates to personal and organizational goals. They have defined the characteristics of an individual’s emotional intelligence for career development. For an individual to achieve success within an organization, they include an individual’s self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management. Bradberry and Greaves also add that a leader should understand self to skillfully respond and advance organizational goals. Therefore, an individual with high emotional intelligence understands self and others and can appropriately lead toward positive change. Applying this definition to pastors, a pastor who is self-aware and socially aware is better able to lead their church toward a common goal.

Several studies show the importance of interpersonal competence as a category for leadership success (Hudson, 2017; Oldenkamp, 2018; Thomas, 1995; Thompson, 1995; Woodruff, 2004). Bradberry and Greaves (2003) have concluded that 90% of high performers also have high emotional intelligence. They attribute emotional intelligence as the single greatest factor of a leader’s success (2009). Roth (2011) corroborated Bradberry and Greaves’s conclusions on emotional intelligence in his study of pastors leading church revitalizations. In Thomas’s research (1995), high-performing pastors in Cuba also showed strong characteristics of emotional intelligence. Though the premises of Roth and Thomas’s studies vary, the results indicate the importance of emotional intelligence in pastors, regardless of church context or organizational circumstances.

Emotional Intelligence and Spiritual Formation

Despite the conclusions from Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso or Bradberry and Greaves, these findings do not always account for the spiritual competence of pastors. Church authors and church researchers consistently include a spiritual component (Payne,2009; Reeder & Gragg, 2008). To reduce the success of the pastor to interpersonal competence in the same way as Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, or even Bradberry and Greaves, would be unfair because their research does not include a spiritual competence in the scope of emotional intelligence. Models provided by David Powlison or James Estep and Jonathan Kim, which focus on intersecting faith and secular sciences, could help guide the conversation where emotional intelligence excludes spiritual competence.

David Powlison (2007) argues that a Christian review of modern psychotherapies should include three phases: (1) start with the Bible as a theological base, (2) critique and reinterpret using Scripture, then, (3) learn from the positive contributions. Similarly, Estep and Kim (2010) suggest several models for evaluating modern psychotherapies, including a framework that starts with biblical theology, evaluates the pro or cons of the idea, then suggests how to apply learnings and discard anything that does not coincide with a biblical theology. By combining Powlison’s model with Estep and Kim’s model, the first step is to find a biblical or theological base that can be applied to emotional intelligence. This article suggests using imago Dei, or man in the image of God, because it is all-encompassing of man’s purpose and substance as it relates to God and faith development (Gentry & Wellum, 2012; Estep & Kim, 2010;Elmer & Elmer, 2020). A pastor or church leader acknowledges their faith to become more self-aware of motives and personal traits. Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso, as well as Bradberry and Greaves, do not reference spiritual influences that may affect a person’s emotional intelligence.

The next step in evaluating emotional intelligence, based on the combined schema of Powlison and Estep and Kim, is to critique and reinterpret. Because Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso and Bradberry and Greaves do not include spiritual competence in their models, a gap exists in the research when considering that church authors and researchers regard faith as an important component of leading a church. Dallas Willard’s (1998) “golden triangle” from Divine Conspiracy could serve as a more rounded interpretation of spiritual formation with connectivity to personality and emotional intelligence. In Willard’s model, the apex is alignment with God, the left side represents the circumstances that God uses to impact the individual, and the right side represents the individual’s intentional persistence in discipleship that may include personal and spiritual disciplines. Willard points out that while both sides of the triangle are independent, they work toward the same goal of aligning with God’s plan and desires. Bradberry and Greaves’s explanations lean to the right side of Willard’s “golden triangle” because a pastor’s development of personal, spiritual, and emotional intelligence tends to be self-initiated or learned over time.

Finally, using Powlison’s framework for evaluating psychotherapies and a model suggested by Estep and Kim, the final phase is to discern what can be learned from concepts like emotional intelligences. Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso’s (2004) and Bradberry and Greaves’s (2003) contributions show three things about emotional intelligence: (1) emotional intelligence can be learned, (2) there are definable characteristics of emotional intelligence, and (3) when correctly applied, an individual can utilize emotional intelligence to affect organizational change. The research points to emotional intelligence as a relevant skill for pastors.

Emotional Intelligence Across Pastoral Competencies

The emotional intelligence research by Thomas and Roth becomes relevant to pastors in two ways. Thomas’s research distinguishes the relevance of emotional intelligence for high-performing pastors, while Roth’s research concludes with the importance of emotional intelligence for pastors in church revitalizations. However, Thomas falls short in application across cultural contexts because he focused on a limited population (Cuban pastors) and did not specifically attribute the competence of emotional intelligence. Roth’s research falls short because his focus was on church revitalizations, not healthy churches or church plants.

In his book on church emotional health, Scazzero (2003) says, “As go the leaders, so goes the church” (p. 20). For Scazzero, the success of the church is connected to the success of the pastor, regardless of context. Bradberry and Greaves (2003) point to emotional intelligence as a key predictor for leadership success. Given the importance that church authors give to leadership, as well as Bradberry and Greaves’s research that emotional intelligence is a predictor of success, discussing the competencies of pastors will prove helpful to see the impact of emotional intelligence.

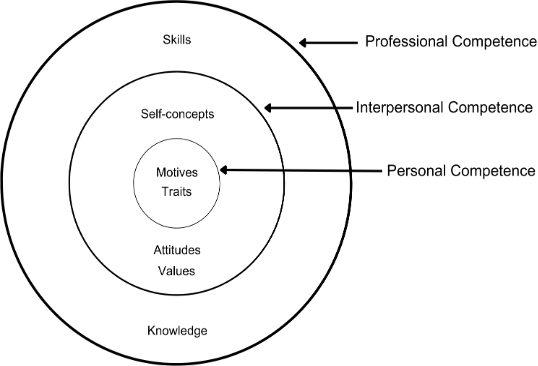

Spencer and Spencer (1993) showed that there are seven individual competencies in the workplace. The seven competencies have been organized into three categories: personal competence, interpersonal competence, and professional competence. Personal competence represents the motives and traits that are consistent in individual personalities. Interpersonal competence is represented by self-concepts; this is where an individual is aware of self and how their attitudes and values influence their interactions with others and impact their work. Professional competence is represented by the knowledge and skills required to do work that is specific to a role (Spencer & Spencer, 1993). For a visualization of the seven competencies and proposed categorization, see Diagram 1. Note that the diagram below was similarly modeled by Thomas (1995) in his research conclusions of high-performing pastoral competencies.

Diagram 1

Spencer and Spencer Competency Model (1993)

Spencer and Spencer’s (1993) definitions for motives, traits, attitudes, values, skills, and knowledge connect with Bradberry and Greaves’s (2009) categories of competence, including intelligence, personality, and emotional intelligence. Bradberry and Greaves define personality similarly to Spencer and Spencer as the characteristics of an individual that are consistent over time, which relate to the category of personal competence in Diagram 1. Interpersonal competence connects to emotional intelligence because both include an understanding of self and of the connected attitudes and values of others. Bradberry and Greaves describe intellectual intelligence as the knowledge needed for an individual to perform a job, similar to the professional competence outlined by Spencer and Spencer. Combining the findings of Spencer and Spencer and Bradberry and Greaves, competencies could connect in the following way:

Personal competence = personality

(self-awareness and self-management)

Interpersonal competence = emotional intelligence

(social awareness and relationship management)

Professional competence = intellectual intelligence

Emotional intelligence impacts each of these competence categories. Research in emotional intelligence predicts knowledge-based performance (personal competence), deviant behavior (personal competence), prosocial behaviors (interpersonal competence), and leadership and organizational behaviors (professional competence) (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2004). When emotional intelligence is applied to Spencer and Spencer’s research, the success of a pastor is relevant in all competence categories.

Spencer and Spencer’s (1993) research showed that 80–98% of competencies were the same within a given profession. Lucia and Lepsinger (1999) concluded that individual competencies remain the same, but behavior may change with context. If both conclusions are applied to pastors, then the individual competencies should be the same regardless of context as a healthy church, church plant, or church revitalization.

Personal Competence

The emotionally intelligent pastor or church leader is aware of their personal motives and traits to lead based on church needs and to cast vision toward the church’s mission. In Malphurs and Penfold’s (2014) study of effective revitalization, they conclude that two traits of successful pastors are dominance and influence. They also define these traits as direct, strong-willed leaders who are sociably influential. Similarly, J. D. Payne (2009) asserts that a church planter should follow a simple relational model for Gospel influence.

In Spencer and Spencer’s model, a pastor’s motive best connects to vision casting because pastors communicate goals through vision. In Planting Missional Churches, Ed Stetzer and Daniel Im (2016) show that the goal of church planting is to send out people to expand the kingdom. Willard (1998) also describes the ultimate end of spiritual formation as alignment in what God desires. Therefore, the pastor or church leader must effectively evaluate their motives to ensure consistency with the purpose of the church to build the kingdom.

An emotionally intelligent leader is self-aware of their traits and motives. Bradberry and Greaves’s (2003) research reveals that individuals must understand themselves before they are able to interact with others around them. A pastor uses self-awareness to self-manage their behavior, emotions, and focus for leadership tasks. Self-management is an important skill in building and leading a team. Conversely, research studies referenced by Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso (2004) found that a lack of emotional intelligence could lead to aggression and that a correlation exists between high-functioning emotional intelligence and psychological aggression. Therefore, emotional intelligence is a helpful tool for leaders but also a potential indicator of poor leadership.

The closest that Spencer and Spencer or Bradberry and Greaves come to discussing spiritual things is through self or personal motives. It remains unclear where an individual’s spiritual competency would best be categorized in their research. Church authors and researchers often do not specifically recognize emotional intelligence but acknowledge elements of it like self-awareness or social awareness without connecting the two like Bradberry and Greaves.

Interpersonal Competence

Stetzer, Malphurs, and others have discussed the importance of a pastor’s ability to lead a team (Stetzer & Dodson, 2007; Malphurs, 1998; Reeder & Gragg, 2008). They summarize that a pastor guides the team toward the goal of expanding God’s kingdom. Spencer and Spencer (1993) note self-concept is a predictor of what individuals will do in situations for themselves and in relation to others. The following excerpt from Spencer and Spencer is particularly helpful.

Someone who values being a leader is more likely to exhibit leadership behavior if he or she is told a task or job will be “a test of leadership ability.” People who value being “in management” but do not intrinsically like or spontaneously think about influencing others at the motive level often attain management positions but then fail. (p. 10)

Additionally, Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso (2004) referenced studies where high-functioning emotional intelligence of leaders led to increased commitment of subordinates to their leaders and to the organization.

Spencer and Spencer demonstrate the need for a pastor to have the appropriate self-image that influences a leader’s success. Bradberry and Greaves (2009) also emphasize that a leader who understands their own self-concept in relation to others will be able to lead positive change. If inter-personal leadership is the ability to lead others through relationships, then a pastor or church leader’s effectiveness could be measured by an ability to influence others toward action consistent with the church’s values. The emotionally intelligent pastor who has motives and traits aligned with Scripture can lead relationally and for the purposes of kingdom expansion.

Professional Competence

Spencer and Spencer’s model leads to the final category of professional competence that includes knowledge and skills for a particular role. In comparison to Bradberry and Greaves (2003), professional competence is similar to the intellectual abilities of an individual to do their job or the capacity of a person to learn how to do a job. Table 1 shows a summary of the perceived professional requirements of pastors. This table includes reviews of different church authors and contexts to test Spencer and Spencer’s finding that 80–98% of competencies for a profession remain the same. Table 1 reveals that pastors in differing contexts need skills in evangelism, developing people, team building, vision, cultural interpretation, and biblical knowledge to lead, regardless of the church’s context as healthy, a plant, or a revitalization.

The relationship between emotional intelligence and personal and interpersonal competence becomes clearer. Most professional skills involve engaging with people, including skills like service, team building, people development, and family. When a pastor or church leader manages self in relation to those with whom they are interacting, then communication, discipleship, evangelism, vision casting, and cultural interpretation thrive. The need to employ emotional intelligence impacts a majority of the professional skills of pastors and church leaders.

Table 1

Review of Professional Competencies

| Malphurs Planting Growing Churches (Church Planting | Malphurs ReVision (Church Revitalization) | Payne Discovering Church Planting (Church Planting | Barna Habits of Effective Churches (Healthy Churches) | Wagner Church Planting for Greater Harvest (Church Planting) | Stetzer Planting Missional Churches (Church Planting) | Stetzer Comeback Churches (Church Revitilization) | |

| Biblical Knowledge | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Family | x | x | x | ||||

| Preaching | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Team Building | x | x | x | x | |||

| Vision | x | x | x | x | |||

| Communication | x | x | x | ||||

| Organization/ Administration | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| People Developer | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Implementer | x | x | x | x | |||

| Servant | x | x | x | ||||

| Culture Interpreter | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Evangelistic | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Discipleship | x | x | x | ||||

| Strategic | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Differing Church Contexts

Spencer and Spencer provide a framework for success within a profession, while Bradberry and Greaves demonstrate individual characteristics that are predictors of success. In combining these paradigms, competencies of pastors are generally the same. Spencer and Spencer’s work helps establish that pastors of healthy churches, church plants, and church revitalizations require similar competencies in each category, most of which can connect to emotional intelligence. Yet, Spencer and Spencer leave a range of 2–20% of competencies that are unique within a profession, and Bradberry and Greaves conclude that emotional intelligence is the most common predictor of an individual’s success (Spencer &Spencer, 1993; Bradberry & Greaves, 2009). Further, Lucia and Lepsinger (1999) concluded that competencies generally stay the same, but behaviors might change when context differs.

Table 2 aggregates competence research similar to Spencer and Spencer’s model. Only three studies were included to demonstrate three primary contexts of churches: healthy churches and high-performing pastors (Thompson, 1995), church plants (Thomas, 1995), and church revitalizations (Hudson, 2017). The research may seem dated, but the available research in pastoral competence is limited, according to Hudson (2017). Each model is based on a study of the desirable competencies for a pastor. Competence categories were reviewed, then ordered or re-ordered to reflect the model provided by Spencer and Spencer. Significant to the compilation of Table 2 is acknowledging that the competence categories created by Hudson, Thomas, and Thompson used a similar methodology to Spencer and Spencer. The primary methodology used to conduct the studies were critical incident interviews that resulted in a compilation of competencies needed in the categories of personal, interpersonal, and professional competencies needed to lead a church. As mentioned previously, competence studies in pastors are somewhat inconclusive partly because approaches vary and not all follow Spencer and Spencer’s model exactly. Table 2 is an effort to identify similarities and differences, even though the research methodologies may have varied some from study to study.

An insight from Bradberry and Greaves (2003) shows that CEOs often display the lowest emotional intelligence compared to other leaders within an organization. While pastors are not technically CEOs, they do represent the church and are responsible to lead members, sometimes similarly to a CEO. The study of emotional intelligence may be incomplete in the observed research due to a potential decrease in the emotional intelligence of higher-ranking leaders within organizations. Pastors reporting on their own perceptions of needed competence for high performance may unknowingly exclude the need for emotional intelligence.

Table 2

Pastor Competence Studies

| Personal Competence | High Performer | Church Revitalization | Church Planter |

| Dynamism/Perseverance | x | x | x |

| Bias Toward Action/ PrudentWorker | x | x | |

| God Focus/Humility/ Recognize Limitations/ GodlyCharacter | x | x | x |

| Strong Self-Image/ Conscientious/ Self-Control | x | x | x |

| Devotion to God/ SpiritualDisciplines/ Love forBible/Prayer | x | x | x |

| Strong Sense of Call | x | x | x |

| Integrity/Above Reproach | x | x | x |

| Family | x | x | |

| Interpersonal Competence | |||

| Involves Others in Work/Team | x | x | x |

| Sociableness/Winsome/Hospitable/Likable | x | x | x |

| Other-Centered/ Sensitive/Flexible | x | ||

| Professional Competence | |||

| Personal Work/ Evangelism | x | x | x |

| Organizational Skill/ Planning/Extension Work | x | x | |

| Training Others/ Discipleship | x | x | |

| Preaching/Teaching/ Creativity | x | x | x |

| Biblical Knowledge | x | x | x |

| Philosophy of Ministry/ Church Discipline/ Gospel Orientations/ Missional Focus | x | x | x |

Observations of Competence Similarities

After review, the combined list includes 16 competencies that remained consistent 87–93% of the time across all studies. The strongest similarity includes a sense of call to ministry, self-concept, and self-image, which appear in the category of personal competence and reflect terminology associated with emotional intelligence. While emotional intelligence was not specifically stated, the terminology was listed in concluding results for healthy churches, church plants, and church revitalizations. Therefore, emotional intelligence is a relevant characteristic among high-performing pastors.

For interpersonal competence, there is evidence that both the ability to work with a team and being socially aware are of high value. For professional competence, Table 2 shows a high value on evangelistic efforts, preaching, and biblical knowledge. While these works do not mention emotional intelligence, references to emotional intelligence emerge with terms such as “sense of call,” “self-image,” and “self-control.”

Observations of Competence Differences

Table 2 reveals similarities between pastors with few discrepancies between each competence study. Yet, the discrepancies are significant. The first discrepancy is how each study modeled results. Thomas (1995) described his competence categories as “personal,” “interpersonal,” and “professional,” while Thompson (1995) described his as “spiritual life,” “church planting skills, and “personal and interpersonal traits.” Hudson (2017) created three categories like Spencer and Spencer but included motives with self-concepts instead of individual traits.

These shifts suggest subjectivity in category creation, which yielded difficulty in the creation of Table 2. While clear distinctive exist in each study, the high-performing pastor excluded family as an individual competence and church revitalization excluded discipleship and training as required professional skills. A bias toward action was excluded from the church planting professional competence, but it is possible that dynamism and perseverance could subsume that skill. The differences create confusion around the consistency in term usage and the perceived importance of emotional intelligence.

Needed Advancements in Pastoral Competence Studies

The discrepancies between these competence studies could be contributed to the 2–20% of individual competencies that are unique, based on Spencer and Spencer’s findings. While Spencer and Spencer’s research is helpful, a consensus between competence study models and terminology does not yet exist. Hudson (2017) observed that work should be done in clarifying terms within church revitalization competencies. If Hudson’s observations are true, then standardizing pastoral competencies could be helpful. For example, Spencer and Spencer (1993) had over 200 contributions, which increases the reliability of their results.

As of this writing, a worldwide catalog search of pastoral competencies yielded less than 50 doctoral dissertations with less than half focused on the role of pastor. The competence studies selected for Table 2 were most like Spencer and Spencer’s competence model and method of research. More work could be done in standardization. Regardless, Table 1 and Table 2 indicate that the skills and competencies needed to be a pastor are the same in healthy churches, church plants, and church revitalizations. As previously referenced, Lucia and Lepsinger (1999) note that behaviors may change based on context. Therefore, while the position of pastor is the same in healthy churches, church plants, and church revitalizations, each context may require a different set of behaviors. A standardized competence model could be helpful to qualify terms and may provide consistency when measuring proficiency of competencies in each church context.

Leadership Application

Given the observations in Table 1, in Table 2, and in Roth’s (2011) study of emotional intelligence in church revitalizations, there is plausible reasoning for including emotional intelligence in the study and writings of successful pastors in all church contexts. Hendron, Irving, and Taylor (2014) reference an article written by Pizarro and Salovey who hypothesized that emotional intelligence could be inherent to religious systems. Hendron, Irving, and Taylor also note that few studies focus on religious populations and emotional intelligence.

Emotional intelligence is an individual competence for pastors and relevant in most competence categories. An awareness of emotional intelligence should be elevated because more senior organizational leaders tend to display lower emotional intelligence. Bradberry and Greaves (2003) demonstrate that emotional intelligence is a key predictor for individual success, so a pastor who is emotionally intelligent could become a successful church leader. They also demonstrate that emotional intelligence can be learned and improved through an action plan. In Emotional Intelligence 2.0, they provide a validated emotional intelligence test with strategies on how to strengthen emotional intelligence. The discipline of growing in emotional intelligence could help a pastor lead better.

A pastor’s increased awareness in emotional intelligence will likely result in better church leadership and could decrease the chances of a church closing. Malphurs and Penfold (2014) concluded that to plant healthy churches, there must be healthy churches. Therefore, a pastor’s growth in emotional intelligence could improve the health of a church, church plant, or church revitalization. As more pastors and church leaders become aware and implement emotional intelligence, there could be an increase of the number of healthy churches, thus potentially slowing the overall mortality rate of churches.

Kevin Spratt is the director of resources for the North American Mission Board and a bi-vocational pastor for young adult and college ministry at Immanuel Baptist Church in Lexington, Kentucky.

References

Bradberry, T., & Greaves, J. (2003). The emotional intelligence quick book: Everything you need to know to put your EQ to work. TalentSmart.

Bradberry, T., & Greaves, J. (2009). Emotional intelligence 2.0. TalentSmartEQ. Earls, A. (2021, May 25). Protestant church closures outpace openings in U.S. Lifeway Research. https://research.lifeway.com/2021/05/25/protestant-church-closures-outpace-openings-in-u-s/

Elmer, M., & Elmer, D. (2020). The learning cycle: Insights for faithful teaching from neuro-sciences and the social sciences. IVP Academic.

Estep, J. R., & Kim, J. H. (2010). Christian formation: Integrating theology and human development. B&H Academic.

Gentry, P. J., & Wellum, S. J. (2012). Kingdom through covenant: A biblical theological understanding of the covenants. Crossway.

Hartford Institute for Religion Research. (n.d.). Fast facts about American religion. http://hirr.hartsem.edu/research/fastfacts/fast_facts.html#numcong.

Hendron, J. A., Irving, P., & Taylor, B. J. (2014). The emotionally intelligent ministry: Why it matters. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 17(5), 470–78.

Hudson, J. (2017). A competency model for church revitalization in Southern Baptist Convention churches: A mixed method study (10682153) [Doctoral dissertation, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary]. ProQuest.

Lucia, A. D., & Lepsinger, R. (1999). The art and science of competency models. Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Malphurs, A. (1998). Planting growing churches for the 21st century: A comprehensive guide for new churches and those desiring renewal (2nd ed.). Baker Books.

Malphurs, A., & Penfold, G. E. (2014). Re:Vision: The key to transforming your church. Baker Books.

Maxwell, J. (2022). The 21 irrefutable laws of leadership: Follow them and people will follow you (25th anniversary ed.). HarperCollins Leadership.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15(3), 197–215.

Oldenkamp, N. G. (2018). Addressing the need for greater social competence of Lutheran Brethren Seminary students entering pastoral ministry [Doctoral thesis, Bethel University]. Spark Repository. https://spark.bethel.edu/etd/480

Payne, J. D. (2009). Discovering church planting: An introduction to the whats, whys, and hows of global church planting. Paternoster.

Powlison, D. (2007). Cure of souls (and the modern psychotherapies). The Journal of Biblical Counseling, Spring, 5–36.

Reeder III, H. L. (2008). From embers to a flame: How God can revitalize your church (Rev. and expanded ed.). P&R.

Reeder III, H. L., & Gragg, R. (2008). The leadership dynamic: A biblical model for raising effective leaders. Crossway.

Roth, J. (2011). The relationship between emotional intelligence and pastor leadership in turnaround churches (3487845) [Doctoral dissertation, Pepperdine University]. ProQuest.

Scazzero, P. (2003). The emotionally healthy church: A strategy for discipleship that actually changes lives. Zondervan.

Spencer, L. M., & Spencer, S. M. (1993). Competence at work: Models for superior performance. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Stetzer, E., & Dodson, M. (2007). Comeback churches: How 300 churches turned around and yours can too. B&H.

Stetzer, E., & Im, D. (2016). Planting missional churches: Your guide to starting churches that multiply. B&H Academic.

Thomas, J. (1995). Competencies which distinguish between high and low performers: Perceptions of Cuban evangelical pastors. Trinity International University.

Thompson, J. A. (1995). Church planter competencies as perceived by church planters and assessment center leaders: A Protestant North American Study (9533068) [Doctoral dissertation, Trinity International University]. ProQuest.

The North American Mission Board. (n.d.). Why we need more churches. https://www.namb.net/resource/why-we-need-more-churches/

Willard, D. (1998). The divine conspiracy: Rediscovering our hidden life in God. HarperCollins.

Woodruff, T. (2004). Executive pastors’ perception of leadership and management competencies needed for local church administration (3128851) [Doctoral dissertation, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary]. ProQuest.

Zitner, A. (2023, March 27). America pulls back from values that once defined it, WSJ-NORC poll finds. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/americans-pull-back-from-values-that-once-defined-u-s-wsj-norc-poll-finds-df8534cd