Abstract: Leadership development through experiences is thought to be one of the most effective approaches in the development of leaders. Exploring the types of experiences of executive church leaders adds to the body of leadership development research focused on leadership lessons, and reveals the contexts through which these experiences were formed. This study applies a phenomenological approach to capture the essence of the leadership development experiences of several bishops within a single African American denomination. Six major themes emerged as important elements of their collective experience. These findings suggest that leadership development experiences for executive church leaders should include ministry venture creation, the use of relevant and real cases, and mentoring relationships.

Keywords: leadership development, leader development, experiences

Introduction

Ascending to executive leadership within a church organization with as many layers and responsibilities as a church denomination, is a complex and sometimes frustrating journey. One’s individual calling to this level of leadership, and the types of experiences necessary to effectively manage the role can be a constant internal debate. Furthermore, for most accepting this calling, formal preparation is self-directed and without a singular path. These executives “discover” treasures of experiences which add context for executive decision making and helps them to frame complex situations.

To illustrate this point, one of the participants, Bishop January reflected on his ascension to the bishopric. He noted how his being passed over for bishop early in his career impacted him personally and professionally. At 45 years old, despite receiving the endorsement of 90% of his peers for the executive role, the denomination’s senior leader selected someone else. “Instead of getting mad with the national church, I looked at myself and said, ‘What is it that you can do better so that next time would be different.’” He further reflected, “I’m smart enough to be bishop, I’m popular enough to be bishop, but if they would have made me the bishop, those older men would have killed me.” It is discoveries like those above which have been analyzed and developed into themes. Several executive leaders holding the title of bishop within a single denomination were interviewed in order to provide insight into their collective leadership development experiences.

The participants in this study are members of a predominately African American denomination with an ecclesiastical structure. The denomination currently has over 100 regions internationally and throughout the United States. As part of the general assembly, the bishops have jurisdictional responsibilities which include the management of tens of churches. Management of the region is done with the assistance of other jurisdictional officers, local pastors, and lay people. Candidates for jurisdictional bishop are normally nominated and asked to present their intentions for the jurisdiction; however, it is the presiding bishop who makes the final selection. The jurisdictional bishops are members of the denomination’s board of bishops, and can be one of the 12 individuals selected to be on its general board.

I first became interested in executive church leadership after seeing my pastor, who was also a bishop, juggle his responsibilities as a father, pastor, and executive on my denomination’s national board of bishops. My childhood questions were: Why does his robe look different from the other pastors? And why is he sitting on the big platform while the other pastors are sitting on the floor level with me? My adult questions were: What makes him qualified to lead at this level? Where did he get his training for executive leadership? Now after being equipped to properly investigate questions like these, my focus of inquiry centers on executive leadership development in church denominations, and more specifically, the experiences they have had that have shaped them as leaders.

Leadership development, and the more specific focus on the development of individual leaders, remains a dynamic and progressive area of research (Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturn, & McKee, 2014). The nature of leader development which emphasizes individual knowledge, skills, and abilities, and develops the intrapersonal abilities necessary for leadership (Day, 2001), has been clarified, and the subjects of leader development and leadership development research expanded. However, more needs to be learned about the individual knowledge, skills, abilities and intrapersonal requirements for executive leadership in church organizations. The research presented in this manuscript builds on a well-grounded line of leadership development research: “lessons of experience” (Douglas, 2003; McCall & Hollenbeck, 2002; McCall, Lombardo, & Morrison, 1988; McCauley & McCall, 2014; Van Velsor, McCauley, & Rudermann, 2010) and explores the development experiences of a set of executive level church denomination leaders.

The next three sections: Testimony for Experience, Executive Leadership Is Different, and Enhanced Development for Executive Church Leaders, provide insight into the reasons for a specialized approach for focusing on experiences. The use of the terms “leader development” and “leadership development” in this manuscript refer respectively to the individual versus collective development of leaders.

Testimony for Experience

Bishop Charles Duke described what and how his experiences influenced his development. Prior to becoming the executive leader of his jurisdiction, he worked with leaders responsible for multiple numbers of churches, and was keen to observe what to do and what not to do. While working with the presiding bishop of the denomination, he gleaned “knowledge about leadership, program implementation, and the tools necessary to enhance and empower communities, organizations and jurisdictions.” He was exposed to other leaders in the jurisdiction, which he believes influenced their decision to endorse him as bishop. The exposure allowed him to observe more facets of the denomination than would be normally afforded to a local church pastor. Furthermore, he learned to appreciate the weight of responsibility which comes with jurisdictional leadership, and the challenge of bringing leaders together.

As a pastor, you have people, and there’s this . . . level of respect that kind of comes as our spiritual leader, our father, our visionary—but when you manage pastors, it’s a whole different world. You deal with their egos, you deal with their visions, you deal with their understandings—they don’t like to be seen as individuals who don’t know, don’t comprehend, don’t apprehend—so you have to learn how to unite them together and build a team. (Sparkman, 2012, p. 67)

The bishop spoke of having to deal with resistance to his appointment as a bishop, and what seemed to be a personal bias against him. Soon after being named bishop, his authority was challenged along with unwillingness on the part of others to address long-standing organizational issues. Characterizing what he felt to be the sentiment of some followers towards him, he said,

I wanted him as bishop, but I didn’t want him to lead us. I don’t want him to change my comfort zone. I don’t want him to expose the methodology of what I’m doing that may be unfruitful, ungodly, illegal, or not the best practice. (Sparkman, 2012, p. 67)

This experience helped him to realize the importance of doing his best to get “buy-in,” but to also understand that “sometimes what you have to learn is that some people are not going to like you, participate and work with you, even if you turn flips or whatever” (Sparkman, 2012, pg. 67).

Reflection on these kinds of situations is tantamount to a lifetime of formal business cases. Even though the experiences are specific to him, the lessons emerging from them are applicable to others at this level of leadership. What should also be clear is the unique nature of executive responsibility.

Executive Leadership Is Different

Executive leadership as a concept and practice is distinguished from leadership at other levels by the roles, behaviors, responsibilities, and challenges faced by those who hold the positions. Zaccaro (2001) defines executive leadership as:

That set of activities directed toward the development and management of the organization as a whole, including all of its subcomponents to reflect long range policies and purposes that have emerged from the senior leader’s interactions within the organization and his or her interpretation of the organization’s external environment. (p. 13)

The executive leader acts and thinks in ways that strategically focus the organization on both internal and external objectives. According to Boal and Hooijberg (2001), effective strategic leaders have adaptive capacity: the ability to change through cognitive and behavioral complexity; absorptive capacity: the ability to learn, recognize, assimilate, and apply new information; and flexibility and managerial wisdom: the combination of discernment in applying social intelligence, and taking the right action at the right time.

In the context of a church denomination, the roles, behaviors, responsibilities, and challenges are more complex, and the strategies have deeper ramifications than those of a local pastor. Borden (2003) states that “the leadership skills required to lead and direct larger congregations are vastly different from those required to lead smaller ones” (p. 58). Sparkman (2010) affirms the qualitative difference between a senior executive church leader (i.e., bishop) and a local church pastor. Noted in this study were the differences in the potential impact of leadership, and the nature of their calling to the executive level. Additionally, executive church leaders exercise behavioral and conceptual complexity as they act in accordance to the varied perceptions of their role. In response to the many different impressions congregation members have of the executive position, executive church leaders must adjust their leadership behaviors and style. Conceptual complexity is demonstrated as they handle novel problems inside and outside the denomination; this includes their community and civic responsibilities. This also includes their attempts to address operational issues emerging as a result of changing perceptions of the role of denominations (Lummis, 1998). Finally, a primary responsibility of those who hold this position is to provide visionary and inspirational leadership. For those examined in this study, visionary and inspirational leadership means projecting a vision and strategy for the entire denomination and the respective jurisdictions they lead. The nature of executive church leadership requires effective leadership development.

Focused Development for Executive Church Leaders

Traditionally, the development of executive ministerial leaders begins through formal education, as ministers pursue such degrees as a master of divinity, and doctor of ministry. Divinity schools and seminaries offer courses in practical theology which instruct ministers how to execute general pastoral duties. Seminars and workshops also support ministers by providing learning opportunities related to both spiritual care and administrative leadership. For example, the U.S. Catholic Church leveraging its association with the National Leadership Roundtable of Church Management (NLRCM), provides seminars focused on management, human resource development, and finance. Executive leaders in the Catholic Church learn from the experiences and knowledge shared by McKinsey and Co. and J. P. Morgan, among others (NLRCM website, 2010). Church consulting organizations, like New Church Specialties, have also worked with over 20 different denominations to offer specific training for judicatory leaders and local pastors and ministers.

While the acquisition of degrees, workshop participation, and the development of learning consortiums can help prepare ministers for executive level leadership, these efforts are basic, relatively scarce, and don’t provide the specific experiences necessary for the respective contexts. Typically, the masters of divinity and doctor of ministry degrees are directed toward current and future local church pastors. The curriculums provide a broad base of knowledge, but not the specific information needed for executive leadership. Judicatory workshops have limited impact in that they are normally offered to, and through, members of a specific denomination. Given the importance of executive leadership, and the paucity of requirement specific options, it is obvious that more should be done.

The current state of leader and leadership development research and practice holds promise for the development of leaders. One of the first studies to explore the effectiveness of management and leadership development programs was Burke and Day’s (1986) meta-analytic review. Their analysis of studies from 1951–1982 suggested that certain managerial training methods could be considered moderately effective in improving job performance and learning. Collins and Holton (2004) also conducted a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of managerial leadership development programs from 1982–2011, again affirming the effectiveness of certain types of managerial leadership development programs. However, it is the “leadership-development-through-experiences” approach which holds the most promise for executive church leaders (McCall, 2004).

As suggested by McCall (2004), “the primary source of learning to lead, to the extent that leadership can be learned, is experience” (p. 1). Contrary to competency models focused on lists of leadership attributes, experience integrates individual leadership styles and behaviors and offers a better foundation (McCall, 2010). Learning through experiences promotes outcomes related to mastery, versatility, and transfer (Yip & Wilson, 2010). Given the uniqueness of executive church leadership, and the challenge of formally developing them, leadership development through experiences seems more expedient.

Views of Development Experiences and Executive Leadership

This study of the developmental experiences of several executive leaders in a single church denomination builds on leadership development research focused on developmental experiences. McCall, Lombardo, and Morrison (1988) and Yip and Wilson (2010), respectively conclude that influential relationships and tough assignments are essential in the development of leaders, and report several themes which support development including: developmental relationships, challenging assignments, coursework and training, adverse situations, and personal experience.

Leadership development through experience is considered an efficacious method for building leadership capacity. It is also thought that executives who learn lessons through experience develop at a faster rate and obtain higher levels of leadership (Dean & Shanley, 2006). Contrary to competency models which prescribe a list of standardized leadership attributes, experience provides a strong foundation (McCall, 2010) and accommodates unique leadership styles and behaviors. Developmental assignments and action learning, as specific practices that support development through experience, offers learners an opportunity to lead across functional and cultural boundaries (McCauley, Kanaga, & Lafferty, 2010), and address real organizational issues which have organization-wide implications (Kuhn & Marsick, 2005; O’Neil & Marsick, 2007).

Collectively, these studies show the range of contexts this line of research can address. For example, in their own study (Yip & Wilson, 2008) of the lessons of experience for targeted public service leaders in Singapore, McCall and Hollenbeck (2002) queried executives in the Netherlands and Japan; and Douglas (2003) described the events and lessons of African American managers in the United States. Executive church leaders also have stories to tell. The lessons they learned and the events associated with those lessons are described in this study.

The perspective of executive leadership as a qualitatively different type of leadership also shapes this study. Examining executive leadership research models, Zaccaro (2001) asserts that four types of models summate the ways that executive leadership has been studied. Executive leadership research comprises behavioral complexity, conceptual complexity, strategic decision making, and visionary/ inspirational leadership models. Respectively, executive leaders modify their behaviors given their multiple roles, responsibilities and social complexity of its organization and external environment. Executive leaders exercise conceptual complexity as they encounter the novel and loosely defined problems which emerge. They attempt to align environmental facts and internal capabilities to fulfill organizational objectives, and executive leaders construct and communicate an organization-wide vision. In this study, the executive leaders are jurisdictional bishops, who hold responsibility for the strategic direction of several churches within their denomination. They collectively craft a vision for the entire denomination and obligatorily adjust their behaviors and leadership approaches in order to lead.

Further Benefits

This inquiry of the leadership development experiences of senior executive church denomination leaders is important for three additional reasons. First, the findings of this study benefit both the individual church leader and church denomination. The individual may pursue similar experiences to those described or the organization may consider creating opportunities resembling those described. Second, it adds to the body of knowledge of several research fields: individual leadership development, human resource development, and executive leadership in a religious context. Third, the findings richly present the essence of the lived experience of these senior executive leaders. They capture the collective understanding of what it took for these individuals to ascend to the highest levels of leadership. The essence of their developmental experiences follow a description of the research challenges and research design.

Examining the Development Experiences of Executive Church Leaders

As the study was designed to provide an in-depth description of the leadership development experiences of senior executive church leaders, it does not include lower-level leaders (such as local church pastors). The potential for bias in interpretation of the research findings also exists. The researcher’s experience as a local church pastor may influence the perception and reporting of their experiences. In order to address these biases, the researcher created an interview protocol and explained to the participants the research procedures, the potential benefits, hazards and participatory options. Credibility issues were managed with the use of three validity strategies: intensive engagement, rich description, and member checking (Creswell, 2007; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Maxwell, 2005; Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Research Design

The purpose of this study was to understand the leadership development experiences of senior executive leaders of a church denomination. An examination of what and how these experiences influenced their development as executive leaders resulted in a description of the essence of their leadership development experiences (Creswell, 2007). A phenomenological approach was applied to capture the participants’ understanding of their leadership development experiences.

Several potential participants were selected and contacted with the goals of establishing the representativeness of the individuals and their setting, and examining a case central to the theoretical framework–leadership development through experience and executive leadership (Maxwell, 2005). Eight out of the fourteen jurisdictional bishops contacted agreed to participate. Each of the men pastored a local church and led a jurisdiction of at least 20 churches. Their leadership of multiple numbers of churches, navigation of the people and polity issues which come with executive leadership, selection and development of middle and lower-level leaders, as well as the creation and dissemination of denominational, jurisdictional and local messages supported their qualification as executive leaders. The researcher visited several midwestern research sites across the United States including Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Oklahoma, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

A modified version of Seidman’s (2006) in-depth interview method was used to develop a substantive and rich description of the collective experience of these unique leaders. The interviews were designed to contextualize the respective experiences, capture the details of their experience, and encourage reflection by the participants on the meanings of their respective experiences. The interviews were 80–120 minutes apiece. An interview protocol with several open-ended questions was used and all responses were recorded and transcribed.

The data collected was analyzed with regard to Moustakas’ (1994) application of Stevick (1971), Colaizzi (1973), and Keen’s (1975) approach to analyzing phenomenological data. A synthesis of textural and structural meanings and essences are the result. The qualitative software, ATLAS.ti, facilitated the analytical process by providing space to store the individual transcripts, delineate and track significant statements, record thoughts about these statements, and construct and visualize individual and collective thematic networks and sub-themes.

The Leadership Development Experiences

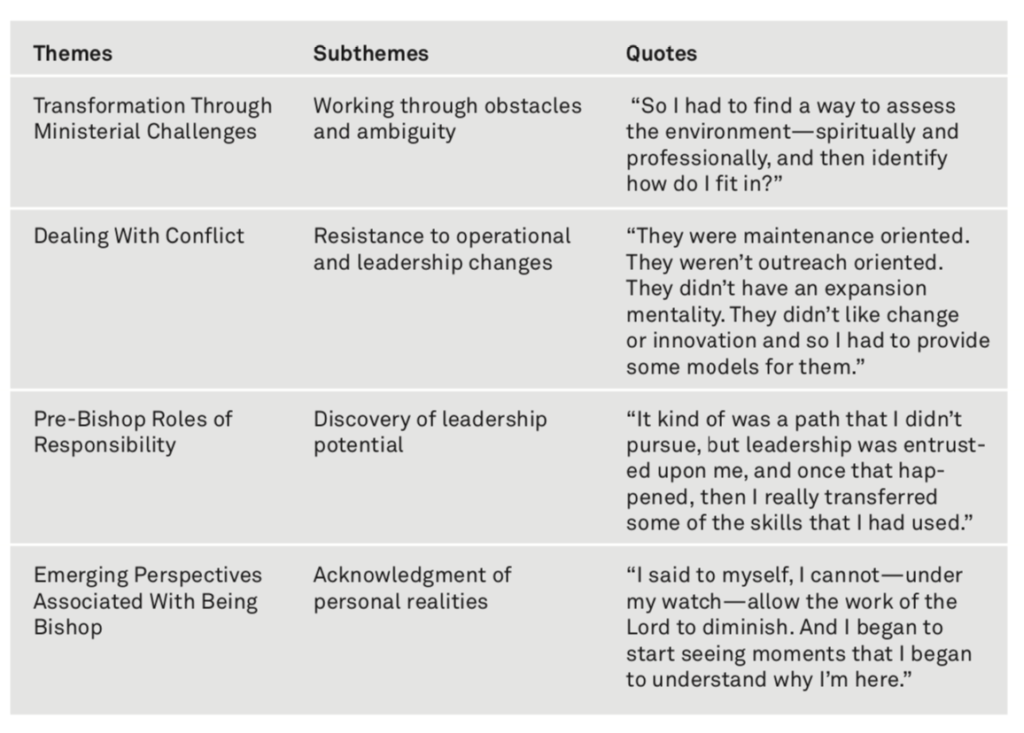

The analysis and synthesis of meanings formed a collective understanding of the leadership development experiences of these executive leaders. Their experiences can be described through six major themes (i.e., transformation through ministerial challenges, dealing with conflict, pre-bishop roles of responsibility, use of formal training, emerging perspectives associated with being bishop, and experiential relationships) (Sparkman, 2012). Table 1 shows some of the themes and subthemes along with the quotes associated with them. These executive leaders understand their leadership development experiences to have emerged from their individual circumstances, their processing of conflict, relationships, and roles, as well as their use of the formal training, and perspectives gained before and after becoming bishop. For the purpose of this manuscript the major theme of “experiential relationships” is described here.

Themes, Subthemes, and Supporting Quotes.

Experiential Relationships

Perhaps the richest theme associated with the bishop’s common experience with the phenomenon of leadership development through experience is experiential relationships. Experiential relationships captures the ways bishops have been influenced by significant individuals. This theme elucidates the opportunities and types of knowledge that came as a result of these relationships. Recalling long and short-term encounters with individuals who strongly influenced their approach and thoughts about leadership, they spoke of relationships with other jurisdictional bishops prior to their appointment. They discussed opportunities to observe the executive leader’s behaviors, and listen to the wisdom offered. As they watched the leaders conduct meetings, and while they ate and traveled together, thoughts about what they would do in certain situations began to emerge. Relationships with their pastors and family members also left indelible impressions.

For the bishops, the relationships helped them to establish standards of faith and values. Through conversations and object lessons, the values of their mentors are transferred. Most of these leaders had someone in their lives who lived out their faith and encouraged them to do likewise. Bishop Duke, referring to his mother who was a church leader, and his father who was a role model, said “her spirituality [his mother], her level of commitment to God, her faith . . . her unfeigned faith, and then my father’s tenacity. His stress of education and readiness . . . and his whole demeanor, created an assurance . . . you can do it.” Another leader referring to the early influence of his parents commented, “We couldn’t half do things. We had to be thorough in what we did.”

The cultural nuances that exist within their organizations became apparent and they acquired knowledge that can only be passed on by those with experience working in these settings. Operational procedure, ministry conduct and approach are learned, while their mentor wears the hat of pastor and executive leader. “And so I was able to watch their dynamics, their religious modus operandi, how they really just carried out what they did. So I saw a side of that on a regular basis, by working very closely with the midwest regional bishops.” Another leader commented, “all of the district meetings, all of the jurisdictional functions from maybe the time I was six . . . had been shaped and formed [not only by] the denomination, but by the personal interest of [the bishop].”

Contending with circumstances which did not involve them directly creates opportunities for lessons learned through those to whom they are close. The personal struggles of those they admire provide a type of lesson learned at the expense of someone else. Vicariously living through the struggles of other leaders, they attempt to understand how and why that leader dealt with those struggles in such a manner. Those vicarious experiences induced thoughts about how they would handle a situation, and why that thought would or would not have been the right one given the eventual outcome. “My pastor was a bishop, and I began to recognize some difference as he dealt with us as members, and as he dealt with men in the jurisdiction. I noticed things like patience. He would let men talk, sometimes I thought, too long.” Another participant said of his mentor who was named an executive leader at a relatively young age, “Several times I saw them [the older men] trying to provoke him into things, and I was saying, ‘Oh, he’ll be there on Friday and he’s really going to set the record straight.’ He gets there and preaches something that had nothing to do with what’s going on. . . . and it’s only later that I’m understanding what he’s doing. He’s saying, I can ruin my whole bishopry [time in the office of bishop], trying to straighten out some personal issue that somebody else has going on. So all of that is filtering into me.” These personal and professional relationships with executive leaders prior to their own appointment become a forewarning of the pressures of executive leadership. It was a time when they could hear the conversations, observe intimate administrative details, and even learn about the social and health problems of their mentor.

They are encouraged, and sometimes coerced into experiences which stretch them. Opportunities to utilize their skills and abilities came when the leaders they worked with gave them a platform for development. Whether the mentor/leader stepped aside to allow them to complete an assignment the leader would normally do, or create a task to encourage their natural assertiveness, the opportunity led in a public way to sharpen their readiness for leadership. Accepting the opportunity meant being forced into assignments that could draw the scrutiny of others. By default, those not chosen, especially other ministers, could become judges of the performance even though they had no formal role in the development process. Enduring the sometimes impromptu testing of those who gave the assignment meant overcoming the anxiety of the opportunity and reflecting on what it meant and why it was given. After being asked to preside over the funeral of a prominent pastor’s mother, with many jurisdiction leaders on the rostrum, he later asked his mentor, “Why me?” “he said, ‘Son, I thought you were going to fail like [another pastor]. That’s why I had all these other men here to back you up. I thought you were going to fail.’”

Finally, opportunities like the one mentioned above, purposefully and sometimes inadvertently put the emerging leader in positions that provided the exposure and recognition needed to rise to a higher level. A mentee said, “I had been pastoring for maybe three, four, or five years and [the top denominational executive at the time] saw me at one of the meetings . . . and he said, ‘I want you to keep up with me.’ I don’t want you hanging back.”

The Impact of Experiential Relationships

Leadership development, as described in the above-themed “experiential relationships,” comes in the form of a deeper awareness and demonstration of the behaviors expected by someone who holds executive office in the church denomination. The leaders understand the importance of setting the tone for behavior, as followers view them as the embodiment of spiritual and practical leadership. The executive leader’s behavior suggests to followers how they should approach and respond to spiritual cues, and how they implement

the details of a vision.

Each one of these bishops also had a relationship with a jurisdictional bishop. Their prior relationships with a jurisdictional bishop provided an opportunity to see the jurisdictional office at work, and have an advocate who could help shape their future. These mentors saw their potential and pushed them to achieve. Characterizing the impact, one leader said, “You can have the vision, but sometimes it takes another person to really open up that vision that’s in you.”

After seeing the personal struggles of those they have been close to, they are more prepared to deal with their own personal struggles. They can consider applying the techniques used by their mentors, and benchmark themselves against the level of courage and strength they displayed. Foreknowledge of the responsibilities of executive office, administrative procedures, and cultural aspects of the denomination passed along through their relationships also gives the bishops a realistic view of executive church leadership. It helps them now as they consider how planned initiatives may be perceived by those who follow, and the likelihood of the initiative’s success.

Final Thoughts

Although there is no explicit pathway or formal development process to advance to the rank of jurisdictional bishop, the bishops involved in this study have developed in similar ways. Their paths are similar in that they have endured difficult circumstances, they hold to their faith as a means of perseverance, and they have learned to cope with conflict. Each one of the bishops had a strong relationship with a jurisdictional bishop and held offices at the jurisdictional levels; most have been administrative assistants of district superintendents. Departures from their respective developmental paths include the ages at which they began to discover and appreciate their unique abilities, and the individual effects of their formal training, previous roles and perspectives gained.

The leadership development experiences of the participants in this study suggest that a process for the development of executive church denomination leaders can be constructed. Drawing from the six major themes and their subthemes, it appears that certain experiences and temperament support the development of these types of leaders. The experiences can be understood as those related to their calling to executive leadership, and those related to administrative and ministerial proficiency. The temperaments displayed during experiences indicate mental toughness with compassion, and openness to development from multiple sources. Put simply, executive church denomination leaders develop as a result of their respective spiritual and non-spiritual events and circumstances which encourage and support their feelings about being drawn to a higher level of leadership, and as a result of their willingness to persist, learn, and integrate lessons learned through their personal interactions, formal education, and paradigm shifts.

Building on the findings of this study, several suggestions are made to promote the future development of executive church leaders.

1. Entrepreneurial/ministry development assignments. The development of projects such as church plants and para-church ministries (e.g., homeless shelters, food banks, education or community outreaches, etc.) are good examples. For these assignments the executive leaders would develop a vision for a selected ministry, plan and implement a growth strategy, lead people of various backgrounds, and reflect on the circumstances and lessons learned.

2. Formalized job/ministry track. Working with denominational leaders, the learning professional would help to identify the developmental aspects of current ministry positions, and integrate those into a formalized ministry track. Emphasizing the development of individual abilities, based on positions and offices at the local, jurisdictional and denomination-wide level, the enhancement of individual abilities would be emphasized. A main feature would also include the participant’s involvement with real issues pertinent to the denomination.

3. Use a cohort approach with case studies. Partnering with denominational leaders, learning professionals would develop case studies appropriate for prospective executive leaders, and assist in the development leader cohorts. The prospective executive leaders would work together to assess, identify and apply appropriate interventions to address conflicts, cultural and change issues, and denominational system issues.

4. Mentoring and advocacy. After identifying mentor-leaders at each level, (i.e., local, jurisdictional, and denominational levels), the potential leader would be paired with one of these leaders as they ascend. At the jurisdictional level the mentor-leader would discuss the mentee’s progress in the aforementioned modules, and plan a strategy to deal with accountability issues. Sharing their own experiences and knowledge of the denominations traditions, the mentor-leader would help the mentee evaluate and apply emerging interventions.

References

Boal, K. B., & Hooijberg, R. (2001). Strategic leadership research: Moving on. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 515–549.

Borden, P. D. (2003). Hit the bullseye: How denominations can aim congregations at the mission field. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Burke, M. J., & Day, R. R. (1986). A cumulative study of the effectiveness of managerial training. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(2), 232–245.

Colaizzi, P. R. (1973). Reflection and research in psychology. Dubuque, LA: Kendall/Hunt.

Collins, D., & Holton, E. F. (2004). The effectiveness of managerial leadership development programs: A meta-analysis of studies from 1982 to 2001. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15(2), 217–248.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Day, D. V. (2001). Leadership development: A review in context. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581–613.

Day, D., Fleenor, J. W., Atwater, L. E., Sturm, R. E., & McKee, R. A. (2014). Advances in leader and leadership development: A review of 25 years of research and theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 63–82.

Dean, J. W., Jr., & Shanley, J. (2006). Learning from experience: The missing link in executive development. University of North Carolina, Kenan-Flagler Business School. Retrieved from http://www.execdev.unc.edu

Douglas, C. A. (2003). Key events and lessons for managers in a diverse workforce: A report on research and findings. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Keen, E. (1975). Doing research phenomenologically. Unpublished manuscript, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA.

Kuhn, J. S., & Marsick, V. J. (2005). Action learning for strategic innovation in mature organizations: Key cognitive, design and contextual considerations. Action Learning: Research and Practice, 2(1), 27–48.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE.

Lummis, A. T. (1998). Judicatory niches and negotiations. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the association for the Sociology of Religion, San Francisco, CA.

Maxwell, J. A. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

McCall, M. W., Jr. (2004). Leadership development through experience. The Academy of Management Executive, 18(3), 127–130.

McCall, M. W., Jr. (2010a). Peeling the onion: Getting inside experience-based leadership development. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 3(1), 61–68.

McCall, M. W., Jr. (2010b). Recasting leadership development. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 3, 3–19.

McCall, M. W., Jr., & Hollenbeck, G. P. (2002). Developing global executives: The lessons of international experience. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

McCall, M. W., Jr., Lombardo, M. M., & Morrison, A. M. (1988). The lessons of experiences: How successful executives develop on the job. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

McCauley, C. D., Kanaga, K., & Lafferty, K. (2010). Leader development systems. In E. Van Velsor, C. D. McCauley, & M. N. Ruderman (Eds.), Handbook of leadership development (3rd ed., pp. 29-61). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

McCauley, C. D., & McCall, M. W., Jr. (2014). Using experience to develop leadership talent: How organizations leverage on-the-job development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded source-book. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

O’Neil, J., & Marsick, V. J. (2007). Understanding action learning. New York, NY: AMACON.

National Leadership Roundtable on Church Management. (2010). Consulting page. Retrieved from http://www.nlrcm.org

Siedman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Sparkman, T. E. (2010). Executive leadership in a religious organization: Understanding the leadership distinctions and means for organizational performance (Unpublished thesis). University of Illinois, Champaign, IL.

Sparkman, T. E. (2012). Understanding the leadership development experiences of executive church denomination leaders: A phenomenological approach. (Doctoral dissertation) Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2142/31177

Stevick, E. L. (1971). An empirical investigation of the experience of anger. In

A. Giorgi, W. F. Fischer, & E. von Eckartsberg (Eds.), Duquesne studies in phenomenological psychology (Vol. 1). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Van Velsor, E., McCauley, C. D., & Ruderman, M. N. (2010). The Center for Creative Leadership handbook of leadership development (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Yip, J., & Wilson, M. S. (2008). Developing public service leaders in Singapore (Tech. Rep.). Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Yip, J., & Wilson, M. S. (2010). Learning from experience. In Van Velsor, E., McCauley, C. D., & Ruderman, M. N. (Eds.), The Center for Creative Leadership handbook of leadership development (3rd ed., pp. 63-95). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). The nature of executive leadership: A conceptual and empirical analysis of success. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Dr. Torrence E. Sparkman is an assistant professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, NY. His research focuses on executive leadership among underrepresented groups, diversity and inclusion, STEM career development.