Abstract: Stakeholder theory is useful in identifying individuals or groups that are invested in, benefit from, or are potentially harmed by an organization. This article identifies a weakness in the current literature. Unlike most for-profit organizations where the various groups of stakeholders are relatively discrete, churches frequently have individuals who are meaningful stakeholders in several arenas simultaneously. The same person can be a program participant (customer), volunteer (unpaid employee), elder or deacon (board member), and donor (investor). This phenomenon is labeled the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect herein, and proposed implications for pastors and opportunities for future research are discussed.

Keywords: stakeholder theory, church, conflict negotiation, nonprofit governance, organizational effectiveness

Pastor Smith wanted to give away the choir robes. The church choir had not worn them in years, and Pastor Smith saw an opportunity to bless a smaller church that could not afford to purchase robes of their own. Shortly after the robes had been donated, a young family left the church. Only much later did Pastor Smith find out that the grandparents of that family had originally donated the robes.

Shortly after arriving at his new church, Pastor Johnson suggested canceling a program that was costing thousands of dollars per year and yet only involved 15 people. Pastor Johnson was surprised when three elders and two deacons got angry and ultimately left the church over the situation. Pastor Johnson didn’t know that of the 15 people in that ministry, five of them were the wives of the three elders and two deacons who left.

Pastor Thompson never would have guessed that firing the youth director for poor performance in discipling students would lead to a drop in giving. Only later did he discover that a couple of affluent families were withholding giving in silent protest of the youth director’s dismissal, as he had reached out to their children, even though most of the other families in the church thought he was ineffective.

During a confidential church board meeting, Pastor Graham asked for prayer for a couple facing marital challenges. The following Sunday, he was yelled at by the wife of that couple for sharing their personal issues “with the whole church.” Pastor Graham was surprised to learn that the wife and one of the board members were distant relatives.

Stories like these play out repeatedly in churches all across the country. Each of these pastors experienced the politics of church leadership that result when congregants hold stakes in the church in multiple different ways. In the book Many Colors: Cultural Intelligence for a Changing Church, Rah (2010) analyzes the unintended consequences of moving the church piano; Rainer (2016) entitled his book on change within the church Who Moved My Pulpit? Even seemingly jovial comments like, “You are our church leaders, and we trust you to make changes in the church—just don’t get rid of the donuts,” reveal the tenuous, complicated, and sometimes strained process that pastors and church leaders experience when implementing change in a church.

These challenges cross over church polity, denominational affiliation, theological orientation of the church, and even church size. They are common across every doctrine and denomination, largely because churches are voluntary affiliation organizations that are dependent upon congregants who attend programming, serve on leadership teams and committees, and donate to the church. The intersection and interweaving of the interests, passions, desires, priorities, and commitment of church congregants adds layers of complexity to even seemingly simple decisions. Understanding and identifying the stakeholders in a church will help church leaders untangle the web of complexity and better comprehend the interconnectedness of members and congregants’ responses to changes in the church.

Definition of Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder theory developed as a response to—and in many ways, a rejection of—prior models for understanding the purposes of organizations. Instead of focusing solely on wealth creation for the benefit of the organization’s owners, stakeholder theory has attempted to articulate an understanding of the responsibility to all those with a vested interested in the welfare of the organization, who benefit from the organization, or who may be harmed in some way by the organization (Laplume, Sonpar, & Litz, 2008; Weiss, 1995). Freeman (2010), credited by many as the father of stakeholder theory, defined a stakeholder as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives” (p. 46). Subsequent work in the field expanded the definition of a stakeholder to include “any person, group or organization that can place a claim on the organization’s (or other entity’s) attention, resources, or output, or is affected by that output” (Bryson, 2017, p. 42).

Categorization of Stakeholders

As stakeholder theory grew in influence and became a dominant paradigm by which to understand organizations, there has been intentional work to categorize stakeholders. One approach was to categorize groups of stakeholders as either internal or external stakeholders (Freeman, 2010; Van Puyvelde, Caers, Du Bois, & Jegers, 2012). A more nuanced categorization, based on how direct the connection is between the stakeholder and the organization and its outcomes, was developed over time; this categorization included labeling primary and secondary stakeholders.

Stakeholders are sometimes divided into primary stakeholders, or those who have a direct stake in the organisation [sic] and its success, and secondary stakeholders, or those may be very influential, especially in questions of reputation, but whose stake is more representational than direct. Secondary stakeholders can also be surrogate representatives for interests that cannot represent themselves, i.e., the natural environment or future generations. (Partridge, Jackson, Wheeler, & Zohar, 2005, pp. 11–12)

The literature has described primary, secondary, and tertiary stakeholders not simply as being internal or external to the organization but by the immediacy of connection to the organization (or a specific product, team, or decision within the organization) and by the agency that a stakeholder could exert over the decision-making processes within the organization (Bryson, 2017; Van Puyvelde et al., 2012). Every stakeholder either benefits from or is harmed by an organization, with primary stakeholders being the most affected by an organization’s actions.

Consider, for example, the way that Apple records the number of jobs it helps create. Apple frequently advertises the number of people employed directly by Apple and the number of jobs employed by suppliers. In 2017, Apple went a step further to advertise that, in addition to the 80,000 employees in the United States and another 450,000 jobs through their U.S. based suppliers, there were currently 1,530,000 U.S. jobs attributable to the App Store ecosystem (Apple, 2017). Those three groups of employees (i.e., employees of Apple, employees of suppliers, and employees of App Store ecosystem companies) all benefit in meaningful ways from or are potentially harmed by Apple, even as they represent different degrees of immediacy and agency within Apple itself.

As with Apple, churches have internal and external stakeholders and primary, secondary, and tertiary stakeholders that benefit from the church’s existence. Recent research has attempted to quantify the economic impact, or “halo effect,” of a church on its community. One study of churches across three cities found that churches added between $1.2 and $2.5 million to the local community (Cnaan & An, 2018). A second study in Toronto found that a city gets an estimated $4.77 in benefits for every $1 a religious congregation spends on its programs (The Halo Project, n.d.). A third national study calculated the socio-economic impact of religion in the United States at $1.2 trillion (Grim & Grim, 2016). That local communities are external tertiary stakeholders and benefit from churches within their community is both clear and demonstrable. However, the focus of the ensuing discussion will be on primary stakeholders—those who are most directly connected to and have the most agency within the church.

Current Utility of Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder theory is used both descriptively, to describe how organizations operate, and predictively, to predict and anticipate how organizations will operate. Stakeholder theory has been both commended and critiqued on both its descriptive and predictive utility (Bowie, 2012; Mansell, 2009; Narbel & Muff, 2017; Weiss 1995). Today, stakeholder theory has primarily given way to broader discussions on corporate social responsibility and alternative models of understanding organizational purpose (Mason, Kirkbride, & Bryde, 2007; Narbel & Muff, 2017).

While alternative constructs such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) or “relationholders” (Woermann & Engelbrecht, 2019) have largely supplanted stakeholder theory in investigations of an organization’s purpose, stakeholder theory still maintains utility in identifying the individuals, groups, organizations, or institutions that are connected to, benefit by or, potentially, are harmed by any organization. This makes stakeholder theory useful in helping to understand the unforeseen consequences experienced by pastors and church leaders in situations such as the fictional examples given at the beginning of this article.

Multiple Simultaneous Stakeholder

Unfortunately, there has been a dearth of exploration of the utility of the stakeholder theory model in nonprofit organizations, in general, and churches, in particular. Certainly, there has been work done in the governance of churches and the politics involved in church ministry, though none recognizes that this results, in part, from one individual being a stakeholder in multiple areas of the church simultaneously (Anderson & Jones, 1990; Burns, Chapman, Guthrie, & Garber, 2019). There has been some attempt to understand the stakeholder connection between nonprofit and for-profit organizations (Abzug & Webb, 1999). One article helpfully applies stakeholder theory to the identification of stakeholders in nonprofits, which, inherently, have no owners or shareholders; this article investigated how to combine stakeholder theory with agency theory to provide a working framework for accountability in nonprofit organizations (Van Puyvelde et al., 2012). Others have applied stakeholder theory to uniqueness of evaluating nonprofit organizational performance, as they lack probability as a criterion for effectiveness (Willems, Jegers, & Faulk, 2016). Alas, while there is much to be commended in these articles, they still do not identify a core phenomenon encountered by church leaders: that individuals are often stakeholders on a variety of fronts, simultaneously.

Church leaders frequently encounter a phenomenon that is not discussed anywhere in the literature, and yet the effects of this phenomenon are experienced every day by church leaders. Multiple simultaneous stakeholders, as they will henceforth be referred, describes the phenomenon of a single individual having a stake in the organization in multiple arenas at the same time. To the extent that a stakeholder benefits from, is harmed by, and has agency in the organization, that one individual experiences multiple stakeholder arenas simultaneously.

To understand why this is so distinct and important, first consider the stakeholders in a video game store. As can be seen in Figure 1, the video game store has several categories of primary stakeholders: the owner, employees, any investors or shareholders, mall management or landlord, customers, vendors and suppliers, and even the owner’s family. Each of these groups of stakeholders have a vested interested in and directly benefit from the success of the video game store. Mall management, for example, wants the video game store to prosper so the owner of the store will continue to pay rent to the mall. The mutual benefit to the store and the mall is why malls run promotions designed to increase foot traffic in the mall. Facilitating the success of the stores is mutually beneficial to the mall management. Vendors want the store to succeed so they can continue selling their products through the store. Employees want the store to succeed to keep their jobs. An evaluation of the benefit derived by each of these stakeholders would simply indicate that each stakeholder benefits from the store flourishing.

Figure 1

Example of Stakeholders in a Video Game Store Operating in a Mall

Note, however, that these categories of stakeholders are relatively and overwhelmingly distinct categories. Sure, the mall manager may decide to buy a video game for her son for Christmas, but her status as a stakeholder is primarily as the mall manager who, for a moment, also happened to be a customer. The mall manager is not going to tell the owner of the video game store which vendors to use as wholesalers, and no customer is going to demand that the store owner increase the dividend to investors. The video game store owner pays rent to the mall management, pays invoices for products to the vendors, pays payroll to the employees, and offers sales to the customers. Each of these stakeholder categories wants to see the store succeed, but for different reasons and with little influence over how the store actually operates. Each distinct and discrete category of stakeholder has only minimal, and usually incidental, overlap.

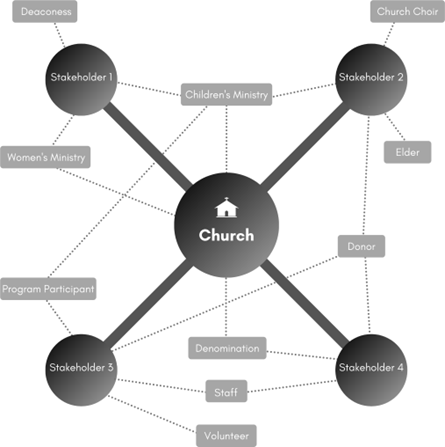

Against the comparison backdrop of the video game store example, consider the stakeholders in a local church, as depicted in Figure 2. A church has congregants and program participants (essentially the church’s customers), volunteer workers, paid staff and employees, donors, a governance board (often comprised of elders or deacons), and, many times, a denominational connection. Whereas the stakeholders in the video game store were relatively distinct, that is not the case in the local church. This comparison is offered precisely because the stakeholders were such discrete groups of people in one organizational structure and are often overwhelmingly the same group of people in the structure of a church. Churches have an organizational complexity that arises from multiple simultaneous stakeholders, yet this has not been well understood in the literature, both to the detriment of churches and scholarly research of churches.

One member of the church could easily be involved as a participant in one church ministry, a volunteer worker in another ministry, give to the church, have children involved in the children’s or student ministry, and serve on the elder board. That one individual could easily be a stakeholder in three, four, five, or more distinct areas—all at the same time.

The term “multiple simultaneous stakeholder” helps explain why the ramifications and results of a change or decision made by church leadership are often very different from the expected outcomes. In each of the situations posed at the beginning of this article, the pastor experienced the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect and likely did not realize it. Pastor Smith did not realize anyone had an emotional attachment to the choir robes, whether they were used or not, but the robes were a reminder of the founding generation of the church. Pastor Johnson experienced that even making the right decision to cut an ineffective and expensive ministry can have far-reaching negative consequences. Pastor Thompson learned that those families who left after the dismissal of the youth director didn’t really care about the health and effectiveness of the student ministry as a whole; they only cared for their own children. And Pastor Graham gained insight into the unseen power dynamics at play between relatives in a church. Because an individual is invested in the church as a multiple simultaneous stakeholder, the effect of change is often multiplied, reverberating to all parts of the church. While the customer at a video game store is not going to tell the owner to negotiate the cost of rent with his landlord, in churches, program participants are frequently given express authority to vote on spending priorities. The supplier for the video game store is not going to tell the store owner to replace the road sign. In a church, that may be a conversation for much or all of the congregation.

Figure 2

Examples of Stakeholders Within a Church

Now multiply that one individual’s state as a multiple simultaneous stakeholder by the number of people in the church. Say a church has eight elders. It would be a realistic assumption that each of those eight elders (stakeholder status: board member) are expected to give (stakeholder status: donor), attend worship (stakeholder status: program participant/customer), and lead a Bible study or serve in children’s ministry (stakeholder status: volunteer worker). Under these assumptions, each of those elders is a multiple simultaneous stakeholder in at least four different areas. In the elder’s meeting, when a sensitive or difficult matter arises, each of the elders is bringing all of their concerns as multiple simultaneous stakeholders to the conversation, not just in the one status of board member. The interwoven web of competing priorities from various board members with various commitments and stakes in the church will show up in these crucial moments.

The Phenomenon in Action

“Human beings, who are almost unique in having the ability to learn from the experience of others, are also remarkable for their apparent disinclination to do so” (Adams, 1992, as cited in Neubauer, Witkop, & Varpio, 2019, p. 91). Neubauer et al. (2019) elaborate, “Perhaps this is because we assume that similar circumstances could never befall us. Perhaps this is because we assume that, if placed in the same situation, we would make wiser decisions” (p. 91). Study of a phenomenon is valuable because it offers insight into the “lived experience” (Creswell, 2008, p. 13) of participants that goes “beyond description of the phenomenon, to the interpretation of the phenomenon” (Neubauer et al., 2019, p. 94). The following is presented as a description of the phenomenon encountered by two church participants, along with a proposed interpretation of their experience.

Tom and Jenny, a married couple, had been members of their church for many years. Over the years, Tom served on the church’s leadership team. Both of them helped lead worship as volunteer staff. Tom and Jenny had one child in student ministry and two more in the children’s ministry, so they were deeply—and understandably—concerned about efforts to disciple the children in the church. Tom and Jenny were also entrepreneurs and rented space from the church to operate their business, making them tenants of the church. One of their children attended the preschool run by another tenant of the church. They were generous donors to the church, giving charitably to the church, even beyond the rent paid to the church through their business.

Conventional stakeholder theory would call for identifying the nature of the stakeholder’s investment in the organization and thereby considering the benefit to be derived. So, what is the primary nature of this family’s relationship with the church? That they are stakeholders is clear. But equally clear is that it is not readily discernible if they are primarily employees, investors, participants (customers), or tenants. Between the two of them, they were either currently or formerly (a) board members, (b) volunteer workers, (c) tenants, (d) program participants, and (e) donors. Additionally, beyond all of those formal affiliations, they also considered themselves close friends with the pastor. Easily discerning their primary stakeholder status is not possible precisely because they are multiple simultaneous stakeholders.

One Sunday, the pastor made the unexpected announcement that he intended for the church to merge with another local church and that the formal vote to do so would occur in one month. This had not been discussed with any lay leaders in the church or any other stakeholders such as renters, donors, or even the congregation. Adding to this shocking revelation, this other church with which it was proposed to merge was of a different denomination. Tom and Jenny had one month to wrestle with the thought of their beloved church merging with a church with different polity (congregational-to elder-led) and different doctrine on baptism, what it would mean for them as renters for their business, and more. Their multiple and varied relationships with the church were interconnected, interdependent, and not easily separated. The unexpected development left Tom and Jenny scrambling to understand the implications for all the various stakes they had in the church. So, what would happen if they didn’t agree with the proposal or at least had questions that were unanswered by the time they were expected to vote? Were they alone in their hesitation and concern? How should they respond?

More specifically to the theory proposed in this article, how could the pastor have used the insights of the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect to shepherd such a monumental change more effectively? Tom and Jenny were just two of many stakeholders, several of which could be accurately described as multiple simultaneous stakeholders as donors, participants, volunteer workers, and more. Each of these multiple simultaneous stakeholders would have their own internal challenges wrestling through their stakes in the church and external challenges as the stakes between stakeholders collided. Here are a few suggestions of ways the pastor could have handled the situation differently.

- The pastor could have phrased the proposal as an idea rather than a decision so that stakeholders could have considered the matter without feeling like their voices didn’t matter or the decision was already final.

- The pastor could have invited stakeholders from throughout the church to investigate the opportunity so that the recommendation on the merger was coming from a group rather than a single individual. Regardless of the polity of the church, every church has formal and informal power brokers (Rainer, 2016) who could have helped facilitate a more positive response if they had been engaged earlier in the process.

- The pastor could have provided time and space for the congregation to evaluate the doctrinal and polity implications of the proposed merger. Doctrinal shifts, especially if they concern significant doctrines like baptism, likely require open dialogue, formal teaching on the subject, and time for stakeholders to understand the implications of the new arrangement.

- The pastor could have gone to the renters ahead of time. In addition to wondering where this left them as members of the church, Tom and Jenny did not know if they would be able to continue renting the place where they ran their business. Now their livelihoods were in jeopardy, not just their church attendance.

Tom, by his own admission, did not always respond well to unexpected circumstances. However, understanding the multiple simultaneous stakeholder phenomenon may have allowed the pastor to identify the implications before the announcement was made, not after. Wise leadership, a direct possible outcome of understanding this phenomenon, potentially could have discerned that this family, and others with multiple stakes in the organization, was a classic case of multiple simultaneous stakeholders. This understanding would have allowed the pastor to invite Tom and Jenny into deeper investment in the church, to both the church’s benefit and their own.

Considerations for Pastors

Comprehending the implications of the tangled web that occurs when many people, all of whom are multiple simultaneous stakeholders, have vested but differing interests in the church will not allow pastors and church leaders to avoid the challenges. But it may allow them to preempt, soften, or even redirect those challenges. Here are four considerations proposed by the author for pastors, flowing from an understanding of the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect: the tenuous nature of commitment to the church, the ramifications of decisions, power and conflict in the church, and the invisible stakeholders who hold significant influence in the church.

Tenuous Commitment

First, the status of being a multiple simultaneous stakeholder shapes the nature of an individual’s commitment to the church. This can either be positive or negative, and probably shifts between the two. Hence the description of that commitment as tenuous. One study found that commitment to the church was not predictive of people holding evangelical beliefs, their faith maturity, or their propensity for moral disengagement (Jeantet, 2018). That is, their commitment to the church is not reflective of their spiritual maturity and is potentially the reason that being a multiple simultaneous stakeholder could be more predictive of their future commitment than their spiritual maturity. The weakness here is that when commitment wanes and a family leaves, the church is not just losing that family from the Sunday attendance count. The church is losing that family from giving, from serving in the nursery, and from whatever other simultaneous stakes that family had. The positive is the opportunity to deepen and foster commitment and engage people in more ways. People give, both with their time and money, to the areas that spark their passions. Who are the donors who seem to lack connection as stakeholders in other arenas? Are there ways to deepen their relationship with the church? At its best, multiple simultaneous stakeholders are invested in, pursuing the growth and development of, and benefiting from the church in myriad ways.

Ramifications of Decisions

Second, understanding the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect can assist pastors and church leaders in anticipating the ramifications of a decision. For example, if money is tight at the church, the church leadership may decide to lay off a staff person. Applying multiple simultaneous stakeholder theory may offer the insight to reveal that the staff member who is to be laid off is someone with whom many in the congregation have a stake. How many people will leave the church because of the decision to lay off that staff person? Sometimes enough people will leave and stop giving to the church that the church ends up not saving any money by laying off that person. The decreased expense without that payroll liability is offset by the decreased revenue from the giving of those who left over the decision. That is not to say the decision is wrong; that is for the church leadership to determine. However, understanding the multiple stakeholder effect may allow the church to better understand the ramifications of their decision-making.

Power and Conflict

Third, the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect offers insight to pastors and church leaders as they struggle with power and conflict dynamics in the church. Going back to the example of the church leadership board comprised of eight elders, each of whom are multiple simultaneous stakeholders in at least four ways, the multiple simultaneous stakeholder phenomenon offers keen insight into why often seemingly small matters become outsized conflicts in the church. Those eight elders are bringing not only their unique personalities, temperaments, passions, and priorities to a conversation. They are bringing competing vested interests. Those vested interests and stakes may not only be competing against the interests and stakes of another one of the elders but often even against the elder’s own stakes.

A financial decision to pursue expanding the children’s playground may come at the expense of the new piano the worship service planning team has been requesting. It’s easy to see how if one elder sings in the choir and the other has children in the nursery, those places for which they are stakeholders will surface in that discussion. Again, consider how that multiplies out by all the various stakeholders in a church. The missions team, rightly, wants to expand the missions impact of the church. The choir wants to replace the aging piano. The children’s team wants the new playground. The women’s team wants to plan a women’s retreat. The facilities team keeps pointing out that the air conditioners are about to die and, with 26 air conditioners in the building, it will be a big expense for which the church better be saving.

Who is “right?” Which group, ministry, or initiative should be funded? It is the task of pastors and church leaders, in this position, to navigate the possibility for conflict by engaging with the various stakeholders in a way that acknowledges the validity of their desires and yet recognizes that not all are possible. Identifying the multiple simultaneous stakeholders and their competing priorities up front may allow a church to avoid painful conflict.

Invisible Stakeholders

Finally, understanding the multiple simultaneous stakeholders within the church may allow the pastors and church leaders to identify the invisible stakeholders who hold significant influence. In many churches, there are matriarchs or patriarchs who, though they hold no official position within the church, are the unofficial power brokers in the church. Everyone, possibly with the exception of the pastor, knows that person to be the one who pushes priorities to the front. That person or family exerts significant influence even without a title. By seeking to identify the multiple simultaneous stakeholders who are vested in any given question, the pastors and church leaders may see that others in the congregation defer to a single person or family in the church. Identifying the invisible or behind-the-scenes stakeholders may allow the pastor to work with such a person to facilitate change, rather than that person consistently being the center of contention and objection.

Considerations for Future Research

The phenomenon of multiple simultaneous stakeholders is easily observed and frequently experienced within churches. However, it has not been researched or fully understood. This article has attempted to articulate several observations about this phenomenon. The idea of multiple simultaneous stakeholders and its effects on nonprofit organizations, in general, and churches, in particular, offers a rich opportunity for future research.

Some of the questions that could be explored by future research include:

- How does being a multiple simultaneous stakeholder impact the individual’s decision-making when priorities are split between those different stakes?

- Does increasing the number of stakes a person has in their church result in an increased commitment to the church?

- Is it possible to quantify the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect?

- Does the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect vary by church polity?

- Are there any secular organization types that, given their unique structure, also have the multiple simultaneous stakeholder phenomenon? If so, what can church leaders learn from those organizations and their experiences?

- What factors may be predictive of the multiple simultaneous stakeholder phenomenon and, similarly, is it predictive of any specific outcomes?

Conclusion

As goes the old adage most frequently attributed to the late former Speaker of the House, Tip O’Neill, “All politics is local” (Gelman, 2011, n.p.). For pastors and church leaders, part of the politics of church is discerning the “what” and “why” of how people respond to a given situation, even if the individuals involved don’t understand their own response. And, because people are complicated, with competing priorities, passions, and interests, pastors often find themselves surprised when a situation escalates quickly or conflict arises over something seemingly small and insignificant. The multiple simultaneous stakeholder phenomenon offers a description of the variety of ways individuals can be stakeholders in multiple ways at the same time in the same organization. By applying the insights derived from the multiple simultaneous stakeholder effect, pastors and church leaders can proactively and preemptively identify potential hurdles so the whole church—pastors, church leaders, and congregants alike—can be equipped to build the church together.

Steve Jeantet, PhD, is the executive pastor of Covenant Life Church in Sarasota, Florida, and the principal of Radical Greatness Leadership Consulting. Steve is a certified appreciative inquiry facilitator, focused on the flourishing of faith-based nonprofits.

References

Abzug, R., & Webb, N. J. (1999). Relationships between nonprofit and for-profit organizations: A stakeholder perspective. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 28(4), 416–461.

Anderson, J. D., & Jones, E. E. (1990). The management of ministry (Reprint ed.). HarperCollins.

Apple. (2017). Apple job creation. https://www.apple.com/job-creation/

Bowie, N. (2012). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art [Review of the book Stakeholder theory: The state of the art, by R. E. Freeman, J. S. Harrison, A. C. Wicks, B. L. Parmar, & S. de Colle]. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(1), 179–185.

Burns, B., Chapman, T. D., Guthrie, D. C., & Garber, S. (2019). The politics of ministry: Navigating power dynamics and negotiating interests. IVP Books.

Bryson, J. (2017). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement (5th ed.). Wiley.

Cnaan, R. A., & An, S. (2018). Even priceless has to have a number: Congregational halo effect. Journal of Management, Spirituality, & Religion, 15(1), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2017.1394214

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press.

Gelman, A. (2011). All politics is local? The debate and the graphs. FiveThirtyEight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/all-politics-is-local-the-debate-and-the-graphs/

Grim, B. J., & Grim, M. E. (2016). The socio-economic contribution of religion to American society: An empirical analysis. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, 12, 1–31.

The Halo Project. (n.d.). Welcome to the Halo Project. https://www.haloproject.ca/

Jeantet, S. J. (2018). Considering a relationship between moral disengagement, faith maturity and organizational commitment: An empirical study of PCA churches in Florida. [Doctoral dissertation, Eastern University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Laplume, A. O., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. A. (2008). Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1152–1189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308324322

Mansell, S. F. (2009). A critique of stakeholder theory. [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Essex]. British Library EThOS.

Mason, C., Kirkbride, J. & Bryde, D. (2007). From stakeholders to institutions: The changing face of social enterprise governance theory. Management Decision, 45(2), 284–301. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740710727296

Narbel, F. & Muff, K. (2017). Should the evolution of stakeholder theory be discontinued given its limitations? Theoretical Economics Letters, 7, 1357–1381. https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2017.75092

Neubauer, B. E., Witkop, C. T., & Varpio, L. (2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2

Rah, S. C. (2010). Many colors: Cultural intelligence for a changing church. Moody Publishers.

Rainer, T. S. (2016). Who moved my pulpit? Leading changing in the church. B&H Books.

Partridge, K., Jackson, C., Wheeler, D., & Zohar, A. (2005). The stakeholder engagement manual: Volume 1: The guide to practitioners’ perspectives on stakeholder engagement. Stakeholder Research Associates Canada, Inc. https://stakeholderresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/sra-2005-words-to-action-stakeholder-engagement-01.pdf

Van Puyvelde, S., Caers, R., Du Bois, C., & Jegers, M. (2012). The governance of nonprofit organizations: Integrating agency theory with stakeholder and stewardship theories. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(3), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011409757

Weiss, A. R. (1995). Cracks in the foundation of stakeholder theory. Electronic Journal of Radical Organisation Theory, 1(1), 1–13.

Willems, J., Jegers, M., & Faulk, L. (2016). Organizational effectiveness reputation in the nonprofit sector. Public Performance and Management Review, 39(2), 476–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1108802

Woermann, M., & Engelbrecht, S. (2019). The Ubuntu challenge to business: From stakeholders to relationholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3680-6