Introduction

Research suggests that, while leaders’ health is a relevant consideration for the health of every organization (Wageman, Nunes, Burruss, & Hackman, 2008), vast improvement in understanding and praxis is urgently required in churches and faith-based organizations (FBOs). Witt (2011) reports the following detractors to pastoral health (Table 1).

Table 1

Witt’s Research on Vocational Hazards in Christian Ministry

| Threats to Sustainability and Well-being | % |

| Pastors who feel discouraged in their roles | 80 |

| Pastoral spouses who feel discouraged in their roles | 85 |

| Pastors who do not have a close friend, confidant, or mentor | 70 |

| Pastors who stated they were burned out, and they battle depression beyond fatigue on a weekly and even a daily basis | 71 |

| Pastors’ wives feel that their husband entering ministry was the most destructive thing to ever happen to their families | over 50 |

| Pastors so discouraged they would leave the ministry if they could but have no other way of making a living | over 50 |

London and Wiseman (1993, p. 22) also report inherent risks in vocational Christian ministry. They found that 75% of pastors reported a significant stress-related crisis at least once in their ministry, 70% say they have lower self-esteem now than when they started out, and 40% of pastors reported a serious conflict with a parishioner at least once a month. More recently, the New York Times (Vitello, 2020) stated that

members of the clergy now suffer from obesity, hypertension, and depression at rates higher than most Americans. In the last decade, their use of antidepressants has risen, while their life expectancy has fallen. Many would change jobs if they could. (n.p.)

Previous frameworks offer well-being solutions that are one dimensional. For example, research has largely been focused on the individual leader’s spiritual practices (Chandler, 2010), physical health (Webb, Bopp, Baruth & Peterson, 2016), compassion fatigue (Pastoral Care Inc., 2015) or psychology (Olson & Grosch, 1991). A substantive chasm exists in the literature regarding the impact of organizational culture on the leader’s well-being.

The current study focuses on the salient comprehensive factors that contribute to the well-being of the leader, such as personal initiatives (personal spiritual growth, coping mechanisms/choices, emotional/mental health, support networks, etc.), and systems initiatives (the health of the organizational context the leader works in). The working hypothesis is that a cooperative effort is needed between the leader and their organization to thrive.

Methodology

This study was conducted using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Three primary research methods were utilized (survey, follow-up interviews and case study of a prayer counselling method). This was done to ultimately develop a way forward with an informed theoretical framework of sustainability in ministry.

The research began with a survey of a sample of 100 ministers from Western nations (e.g., Canada, USA, Europe, Australia and New Zealand) who serve full time in a Christian organization. The participants were senior leaders (72%), associate leaders (17%), support/administrative staff (4%), and other (7%). The average age of respondents was 52 and the average years of ministry service was 23; 86 participants were male and 14 were female. The survey contained thirteen questions and was administered via SurveyMonkey. This method proved effective as an instrument in identifying trends, giving candid comments after each question, and preparing respondents for followup conversations in the next stage of research. The analysis resulted in seven predictive categories of leadership health.

Follow-up interviews were then conducted to confirm the survey findings and to discover connections that the survey results did not yield. Ten survey respondents were interviewed by phone in a free-form format. The seven indicators of leadership sustainability and well-being were confirmed, additional stressors in ministry were divulged, and the composite factor of spiritual/mental processing emerged as the most significant predictor. The interview format proved valuable in understanding a practitioner’s perspective of the practices, policies, and conversations that best serve leaders.

Following the interviews, a study was conducted, utilizing the spiritual/mental method of Dr. Ken Smylie (director of the Pastoral Counselling Center in Gainesville, Florida) in helping leaders increase resiliency through prayer counselling. This method was selected for analysis because 95% of Dr. Smylie’s pastoral counselling clients have indicated an improvement in their emotional and spiritual state based on the Likert Scale, which allowed participants to express how much they agree or disagree with statements. Exploration into the method was conducted through a personal prayer counselling session with Dr. Smylie, analysis of a second case study session recorded on video, and follow-up phone interviews with Dr. Smylie. While people from varying theological traditions may take issue with certain finer points of Smylie’s theology and approach, his prayer counseling sessions’ basic structure can be easily adapted to different theological contexts.

The data was then analyzed and organized into a theoretical framework that fosters awareness, dialogue, and practice.

Seven Predictors of Sustainability and Well-being

The survey results confirm and broaden previous research; these results create concern, reflection, and reform (Green, 2016). Each survey response informs dialogue and praxis as leaders revealed experiences that are not part of Christian organizations’ the common knowledge (see Tables 2–5).

Table 2

Survey Results: Most Common Challenges Christian Leaders Face Monthly in Their Role

| Monthly Leadership Challenges | % |

| Show signs of being burned out, discouraged, stressed, overworked | 58 |

| Experience conflict with those I am leading | 57 |

| See signs of my emotional and mental well-being being negatively impacted | 51 |

| Have concerns about my financial well-being | 39 |

| See signs of a lack of doctrinal agreement between myself and those I lead | 39 |

| My marriage is negatively impacted by this leadership role | 37 |

| The expectations on me are unreasonable | 35 |

Table 3

Survey Results: Top Sources of Stress Experienced by Leaders

| Stressor | % |

| Challenges from the congregation/people | 60 |

| Loneliness/isolation | 45 |

| Financial challenges | 42 |

| Practical theology disagreements (i.e., worship styles) | 25 |

| Lack of agreement with followers over what my role is | 19 |

| Feeling constrained in this position | 18 |

| Tension with other staff members | 18 |

Table 4

Survey Results: Top Ministerial Risk Factors Experienced by Leaders

| Ministerial Risk Factor | % |

| Work more than 46 hours/week | 73 |

| Significant stress-related crisis at least once in ministry | 70 |

| Ministry affected family negatively | 43 |

| Unable to meet demands of job | 39 |

| Inadequately trained to cope with demands | 30 |

| Do not have someone that you consider a close friend | 24 |

Table 5

Survey Results: Concerns Ministers Have if They Consider Leaving Vocational Ministry

| Factor | Responses |

| Concern about stress/burnout | 9 |

| Financial concerns | 9 |

| Conflict/organizational politics | 8 |

| Marital concerns | 8 |

| Lack of organizational support | 8 |

| Desire to explore another vocation | 8 |

| Purpose drift in organization | 7 |

| Lack of support network | 6 |

| Disappointment with God | 5 |

| Violation of a policy | 5 |

Another revealing finding was that only 56% of leaders said they engaged weekly in activities that positively deal with the stress they experience in their leadership role. Palmer (1998) concludes that many pastors are not accessing stress management resources available to them, such as counselling, psychological tools, relaxation techniques, and assertiveness training.

The survey yielded many positive results related to ministerial health. While this may be counterintuitive, Robbins and Francis (2010) confirmed that high levels of job satisfaction and an awareness of the dangers of burnout commonly co-exist in Christian leaders. The levels of satisfaction in ministry that leaders experience in vocational service in key areas are indicated in Table 6.

Table 6

Survey Results: The Top Results for Satisfaction Experienced Weekly

| Positive Factor | % |

| My relationship with God is enhanced | 85 |

| My greatest strengths are utilized | 79 |

| I get excited about the opportunities in my role | 76 |

| Those that I lead show strong signs of support of my leadership | 65 |

| I am shown strong signs of support from my staff | 59 |

The survey indicated that leaders’ most essential refueling fell into four crucial sustainability categories that predict well-being: spiritual, physical, mental, and social (Table 7).

Table 7

Survey Results: Top 12 Practices That are Ranked the Most Important to Leaders for Their Overall Health in Ministry

| Practice | Weighted Responses |

| Read the Bible | 23 |

| Discussions with spouse/friend | 22 |

| Prayer/meditation | 22 |

| Weekly day off | 20 |

| Looking for signs of the activity of God | 18 |

| Regulate thought life | 18 |

| Get adequate sleep | 17 |

| Discussions with advisor | 17 |

| Rehearse what God has done in the past | 17 |

| Input of encouraging content (reading, podcasts, etc.) | 16 |

| Get physically mobile | 16 |

| Tie: hobby; socialize with good friends; intellectual stimulation | 15 |

Leaders also revealed three additional holistic sustainability predictor categories when asked to rank the factors that impact their longevity in vocational Christian ministry: vocational, organizational, and financial (Table 8).

Table 8

Survey Results: Top 12 Factors that Impact Leadership Longevity

| Factor | Weighted Responses |

| I know how to personally and spiritually refuel | 16 |

| Discussions with spouse/friend | 16 |

| I have strong support in place from family and/or friends | 16 |

| I am careful to find alignment between my role and my strengths | 13 |

| I have good self-care practices in place | 13 |

| I know how to manage my expectations of myself | 13 |

| I utilize healthy ways of dealing with conflict | 12 |

| I have a mentor in the denominational/organizational structure | 11 |

| I know how to manage the expectations of others | 11 |

| I access continuing education to help deal with real-life leadership issues | 10 |

| I am reasonably compensated | 10 |

| I serve an organization that has systems in place to provide relief from workloads when leaders are facing conflict/crisis | 10 |

The survey results consequently suggest that well-being best practices be implemented in each of the seven critical areas that predictably create leaders that last:

- Spiritual: Have personal spiritual practices in place that regularly strengthen

- Physical: Take care of their body so they can sustain their ministry vision

- Mental: Regularly renew their minds so that they are redemptively processing ministry experiences

- Social: Build an adequate support network around themselves, of safe people they can decompress with

- Vocational: Engage in the process of aligning their strengths with their roles

- Organizational: Place themselves in and create organizational systems, policies, and procedures that mitigate against stressors

- Financial: Place themselves in and create healthy financial situations so financial concerns are not a distraction

Follow-Up Interview Reveal a Composite Predictor

In the interviews, leaders were asked how they proactively addressed their own need for replenishment. The following sampling of their responses reinforces the seven predictors discovered in the survey.

- Spiritual: “Daily time in Scripture . . . helped (my wife and I) to function better, and it has helped us at least to maintain our level of health (after burnout).” (Dale)

- Physical: “I follow intense periods of work with equally focused rest.” (Jonathan)

- Mental: “The leader must address the lies that the enemy has planted in their minds and replace them with the truth. To speak secularly, they need cognitive-behavioral therapy—taking negative beliefs and replacing them with positive beliefs . . . In this way the spiritual and mental areas overlap.” (Kelly)

- Social: “Have people in your life that you are not learning from or pouring into—people that you can enjoy and be at rest around . . . I find it easy to be serious and maybe too task-oriented.” (Keith)

- Vocational: “I could not lead just any organization. For me, it is all about call and alignment—I believe that is when God’s blessing falls. You must get the right fit.” (Al)

- Organizational: “We will be judged based on how well we allowed the staff to flourish . . . we invest in the people who are leading because ultimately they get the results.” (Owen)

- Financial: “There are times when it is tempting to go do something that makes more money. You get thinking about the future and wondering ‘who will take care of me?’” (Wayne)

The interviews also uncovered nine leadership stressors that the survey did not reveal.

- Unhealthy church culture: “The lack of health in the church was the number one factor that led to my burnout . . . I have been granted one month off to get restored.” (George)

- Unclear expectations: “We experienced tension when the uncommunicated outcomes were not met.” (Mel)

- Unrealistic expectations: “You feel the pressure to find ways to please everyone, although that is impossible.” (Alex)

- Lack of pastoral care: “There needs to be intentional pastoral care for those in ministry. If you feel cared for and valued, you start caring for and valuing others.” (Garth)

- Unhelpful volunteers: “If they are not consistent, punctual, cooperative, team-minded, or soft-hearted, it can be very draining.” (Carl)

- People care and trauma: “Leaders feel they can handle the stress of helping others with their issues and trauma—until they can’t . . . they face similar occupational hazards to those who work in other people-helping professions.” (Bobby)

- Stigma attached to getting help: “Professionals don’t want people in their circles to know they are dealing with something. Ministry people don’t want to be a recipient. They like to wait until they hit a crisis point before they get help.” (Adele)

- Strain on marriage relationships: “Her interests are only important if they are supporting him. This leads to an inequity where there should be partnership.” (Max)

- Challenges for women in ministry: “I was once told that I was getting paid less than a male counterpart in the same role as me . . . although I was more educationally qualified.” (Brynn)

Because gender issues are not within this study’s scope, see Bumgardner (2016) for further exploration.

One composite predictor came to the surface in the interviews more than any area: the combination of the spiritual and the mental. Many responses could have been placed in either or both categories. For example, one leader explained, “I have discovered that I personally need inner healing and deliverance. I need to find the spiritual oasis that will help me to root out the lies of the enemy . . . Otherwise, leaders will not know why they are sad, depressed, angry, and wanting to quit. We have to bring our lives to Jesus for Him to heal us” (Kelly). When the spiritual/mental predictor is given ample personal attention, it makes the leader is more resilient. Kidder (2017) emphasizes a similar approach, but describes it instead as cultivating biblical self-worth, depending on God for emotional health and reflecting on your identity in God.

Improved methods of mental/spiritual processing are also relevant to coping with organizational problems. For example, Gyuroka (2010) maintains that leaders are better served by learning to reframe their leadership challenges (i.e., adapting their way of thinking about problems and being willing to question accepted organizational procedures). Manders (2014, p. 114–115) likewise posits that critical leadership skills include dilemma flipping (the ability to turn dilemmas into advantages and opportunities) and constructive depolarizing (the ability to calm tense situations where differences dominate). Resilient Christian leaders can use this approach to invite God to help them get “the view from the balcony” (Gyuroka, 2010, p. 146) to have a more beneficial lens that helps them overcome leadership stressors.

The sustainability of the leader is thus enhanced by their engagement in processing life and ministry to integrate the spiritual and the mental. In other words, the leader receives God’s help in renewing their mind and, ultimately, their emotional state. This finding prompted the next step in the research process.

Spiritual/Mental Method Increases Leadership Resiliency

A proven expert strategy for spiritual/metal health is the prayer counselling approach of Dr. Smylie. The following is an abbreviated transcription of a live demonstration at the Florida Together for Truth Initiative (Smylie, 2015), where a woman is helped to process the challenges she experienced through a lens of truth. (Note: Dr. Smylie’s prayers are italicized.)

Dr. Smylie: Jesus, would you pick a thought or a feeling or a memory, and would you gently bring it to Claudia’s mind at this time. So, Claudia, just briefly describe whatever comes to mind.

Claudia: As a child, I always heard about how disobedient I was. But I know that wasn’t true—it was maybe a way to control me. And later I was part of a church where they would do the same thing . . . But I think the Holy Spirit was always trying to tell me “that’s not true.”

Dr. Smylie: Jesus, what is the lie? What is the first thing that comes to your mind?

Claudia: That I should not even start to dream that I can get anywhere (in life).

Dr. Smylie: What if you were to say something like “In Jesus’s name, I reject the lie that says (and then fill in the blank).”

Claudia: In Jesus’ name, I reject the lie . . . that I don’t deserve to be who I am or become what God wants me to become.

Dr. Smylie: Do you sense anything?

Claudia: It is easier to breathe . . . it is as if the way is free.

Dr. Smylie: Jesus, would you tell Claudia what the truth is. What’s the first thought that comes to your mind?

Claudia: That I am loved unconditionally.

Dr. Smylie: That sounds like Jesus to me. Is it your will to accept what He says to you?

Claudia: Yes.

Dr. Smylie: Then it’s yours. And what is the emotion or the feeling that comes having made the decision to accept what Jesus says to you.

Claudia: Now I have the feeling that I have space to grow, that I can be who I am supposed to be. I felt like I was in a jail and there was a limit on me, and now I am free.

Dr. Smylie: It’s the truth that sets you free.

Claudia: Now I can breathe . . . now I feel I have more space to grow. Smylie’s process is to enter the prayer counselling session with calmness, gentleness, and a sense of confidence that any negative emotional stronghold can be addressed in counselees. Almost half of Dr. Smylie’s clientele are vocational Christian leaders seeking healing. He reports that he needs to approach Christian leaders with greater sensitivity because of their conceptions of themselves and frequent reluctance to receive help.

In his practice, the top indicators of leadership health/longevity are consistent with the data in this study, specifically dealing with emotional wounds, finding healthy ways to cope with unrealistic expectations, and getting adequate rest. His assessment is that transformative prayer should be part of the foundation of all ministerial training so people can experience personal freedom while they are young and not think it a foreign concept to get help when they are older. Clearly, ministries that address Christian leaders’ spiritual and mental health need to be widely developed, supported, and accessed.

A Way Forward: Developing A Healthy Ecosystem

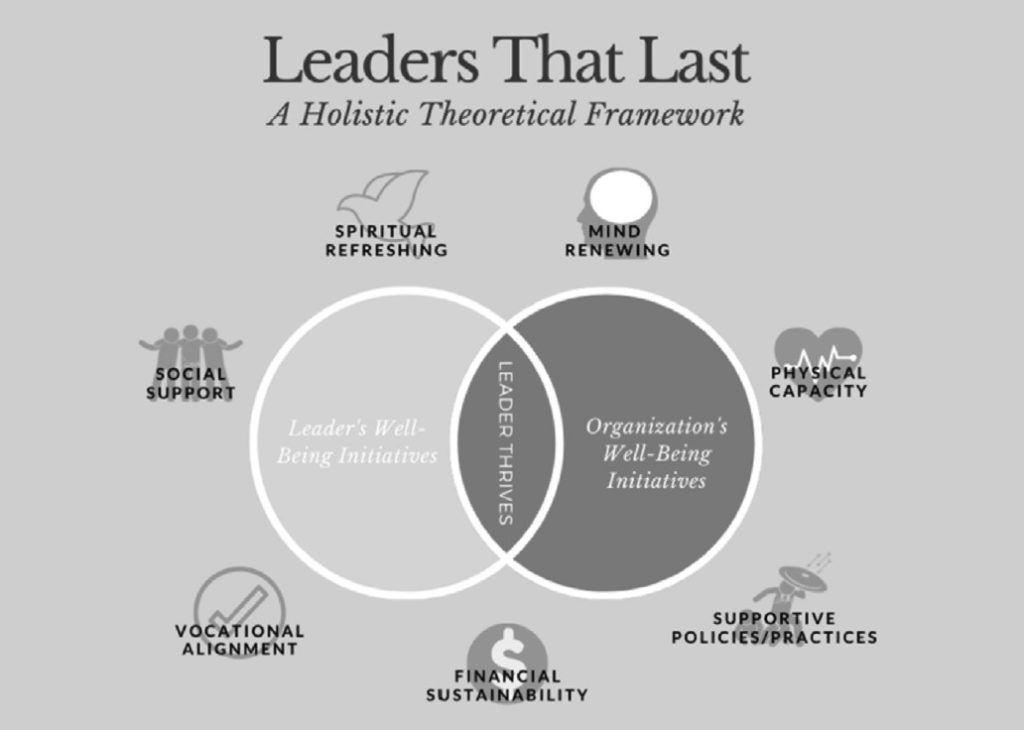

The study’s final stage is the development of a holistic theoretical framework for resiliency in vocational Christian ministry. We conclude that the leader’s well-being initiatives, plus the organization’s well-being initiatives, together provide an ecosystem where the leader can predictably thrive. It is a framework that is multidimensional and multidisciplinary. The framework is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Leaders That Last: A Holistic Theoretical Framework

At the center, this framework encourages mutual ownership of leadership resiliency by the leader and those who supervise him/her. Leaders must exercise their agency to initiate all-encompassing replenishment strategies in each of the seven key areas. The strategic implementation will be unique to each leader as they reflect on what energizes them. Likewise, the organization must be proactive in designing a healthy atmosphere for the leader by engaging the leader in dialogue about how s/he may be supported in each domain. Supervisors can also identify and prepare for potential difficulties for Christian leaders in advance by asking themselves what leadership threats have emerged in the past in their organization and by asking experienced practitioners what they should be aware of when introducing leaders to their ministry. When both the leader and the organization take extreme ownership, the environment is optimized for the leader to thrive.

The domains around the core depict the intentional development of an atmosphere built around the leader by activating initiatives in the seven areas of leadership health. It is holistic in that it encompasses the spiritual and embraces other primary facets of human existence. The framework also suggests an interrelatedness of each of the seven leadership health indicators in the atmosphere around the leader. These areas often overlap, and an increase in health in one area can bring an increase in the health of other areas. A multi-disciplinary approach to leadership health is the most effective (Proeschold-Bell et al., 2011). The church in the West needs a renewed para digm that sees all truth as God’s truth and adopts the best that social sciences and physical sciences have to offer (i.e., breakthroughs in nutritional science, stress management, cognitive therapy, etc.). In another study, Brown (2011) similarly advocates for the abandonment of a single-focused system (a central focus on the welfare of the church) in favor of a multi-focused system (spirituality, health and wellness, relationships, personal growth, activities and interests, etc.). This framework also shows the highest impact areas weighted to the top and the lesser predictors towards the bottom.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the framework confirms that the multidimensional revelation of Scripture better serves us than one-dimensional frameworks. The following is a summary of how revelation speaks to each of the seven indicators of leadership health.

- Spiritual refreshing: “Those who look to him are radiant . . .” (Ps. 34:5a, NIV)

- Mind renewing: “. . . but David encouraged himself in the LORD his God.” (1 Sam. 30:6, KJV)

- Social support: “But God, who comforts the downcast, comforted us by the coming of Titus.” (2 Cor. 7:6, NIV)

- Physical capacity: “The angel of the Lord came back a second time and touched him and said, “Get up and eat, for the journey is too much for you.” (1 Kings 19:7, NIV)

- Vocational alignment: “For this reason I remind you to fan into flame the gift of God, which is in you through the laying on of my hands.” (2 Tim. 1:6, NIV)

- Supportive policies/practices: “Do this so their work (as leaders) will be a joy, not a burden, for that would be of no benefit to you.” (Heb.13:17 NIV, parenthesis added)

- Financial sustainability: “When Silas and Timothy came from Macedonia, Paul devoted himself exclusively to preaching . . .” (Acts 18:5, NIV)

Conclusion

For the mission of the church in the West to thrive, its leaders must thrive. This research brings a deeper awareness of common occupational hazards and predictive well-being factors that will help pastors, educators, counselors, and supervisors put practices, relationships, and systems in place to increase longevity, fulfilment, and fruitfulness levels of ministers. It highlights the need for Christian organizations to be honest and open about the reality of ministry leadership challenges, rather than thinking that Christian leaders are (or should be) immune. The results show that leader’s sustainability is impacted by both personal well-being practices and an intentionally created organizational environment that enables and protects them.

Further areas of research include: (1) exploring gender differences in the experience of Christian leaders; (2) determining specific organizational cultural characteristics and practices that best support the leader; (3) discovering if there are statistical differences in clergy resiliency between countries in the West; (4) finding correlations and contrasts between leadership health levels in the West and other nations and identifying larger social trends that impact resiliency (aging congregations, secularization, two-income households, etc.); (5) analyzing possible differences in vocational satisfaction levels in church and parachurch ministries; (6) determining best practice for leadership transitions that support the incoming leader; and (7) ascertaining whether there are statistical differences between denominations/theological traditions.

As awareness of sustainability and well-being research increases, we anticipate that more Christian leaders in the West will be break free of stigmas about their human limitations and put comprehensive preventative strategies in place. They will feel the support of the organizations they serve. Organizations will take ownership when replenishment strategies have been inadequate, churches will educate their congregations about the stressors in pastoral ministry, and training centers will better prepare Christian leaders for the challenges that lay ahead of them. Ultimately, mutually developed and customized strategies will be put in place to ensure that leaders last.

References

Brown, R. (2011). Revitalization of the church leader (Dissertation Notice). Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 5(2), 1.

Burnette, C. (2016). Burnout among pastors in local church ministry in relation to pastor, congregation member, and church organizational outcomes [Doctoral dissertation, Clemson University]. Retrieved from https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2746&context=all_dissertations

Bumgardner, L. (2016). Adventist women clergy: Their call and experiences. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 10(1), 1–13.

Chandler, D. (2010). The impact of pastors’ spiritual practices on burnout. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 64(2), 1–9.

Clinton, R. (1988). The making of a leader. Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

Elkington, R. (2013). Adversity in pastoral leadership: Are pastors leaving the ministry in record numbers, and if so, why? Verbum Et Ecclesia, 34(1). doi:10.4102/ve.v34i1.821

Green, L. (2016, Feb. 12). Former pastors report lack of support led to abandoning pastorate. LifeWay Research. Retrieved from https://lifewayresearch.com/2016/01/12/former-pastors-report-lack-of-support-led-to-abandoning-pastorate/

Gyuroka, T. (2010). The practice of adaptive leadership. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 4(1), 146.

Kidder, J. (2017, July). From burned out to burning bright: Cures for eight causes of burnout. Ministry Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.ministrymagazine.org/archive/2017/07/From-burned-out-to-burning-bright-Cures-for-eight-causes-of-burnout

London, H., & Wiseman, N. (1993). Pastors at risk. Wheaton, IL: Victor.

Manders, K. (2014). Leaders make the future: Ten new skills for an uncertain world. Journal of Applied Christian Leadership, 8(1), 114–115.

Olson, D., & Grosch, W. (1991). Clergy burnout: A self-psychology and systems perspective. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 45(3), 297–304.

Palmer, A. (1998). Clergy stress, causes, and suggested coping strategies. Church Society, 112(2), 163–173.

Pastoral compassion fatigue. Pastoral Care Inc. Retrieved from https://www.pastoralcareinc.com/articles/compassion-fatigue/

Proeschold-Bell, R., LeGrand, S., James, J., Wallace, A., Adams, C., & Toole, D. A theoretical model of the holistic health of United Methodist clergy. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(3), 700 –720. DOI: 10.1007/s10943-009-9250-1.

Robbins, M. & Francis, L. (2010). Work-related psychological health and psychological type among Church of England clergywomen. Review of Religious Research, 52(1), 57–71.

Smylie, K. (2015, December 17). Inner healing prayer-Dr. Ken Smylie. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bVwOVTdaEo.

Vitello, P. (2010, Aug. 1). Taking a break from the Lord’s work. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

Wageman, R., Nunes, E., Burruss, J., & Hackman, J. (2008). Senior leadership teams: What it takes to make them great. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Webb, B., Bopp, M., Baruth, M. & Peterson, J. (2016). Health effects of a religious vocation: Perspectives from Christian and Jewish clergy. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 70(4), 266–271.

Witt, L. (2011). Replenish. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker.

Rob Parkman, PhD (candidate, VU University Amsterdam), is a leadership revitalization coach, a speaker with Compassion International, and the author of REFUEL (available on Amazon).

René Erwich, PhD, is principal of Whitley College in Melbourne, Australia.

Joke vanSanne, PhD, is rector magnificus at the University of the Humanities in Utrecht, Netherlands.