Abstract: Traditional missionary efforts consist of individuals following God’s leadership of going and teaching people in other lands. Such small-scale efforts are overwhelmed within rapidly changing world populations and amid ever-increasing analytical and technology advancements. This article investigates current practices and financial valuations of expatriates and international missionaries. By integrating business disciplines, evangelistic expatriates will be better positioned to reach biblical goals of discipleship. A modified model and implementation actions are suggested for churches and ministries sending missionaries.

Keywords: missionary, expatriate, business metrics, balanced scorecard, financial valuation

Globalization has heightened the demand for educated, talented workers to temporarily transfer across national borders (Cerdin & Selmer, 2014). A significant financial challenge to organizations is related to the increasing costs in wages and relocation-related expenses. Existing literature provides various classifications for expatriates and valuation instruments for expatriate assignments, yet research on international missionary assignments is lacking.

An expatriate is defined as “a temporary, highly skilled migrant who moves abroad for a period of time” (Millar & Salt, 2008, p. 27). Finaccord (2014) reports over 50 million expatriates worldwide. The “global mobility” industry is valued at roughly $500 billion (market capitalization of companies in the industry).This industry has evolved to help organizations relocate their workforce abroad as well as other services such as immigration, tax compliance, and cross-cultural training (Cranston, 2018).

The purpose of this article is to discern how finance professionals working in Christian ministries can leverage valuation and business principles for expatriate assignments, allowing them to evaluate and enhance international missionary assignments. The remainder of this article includes a literature review that highlights the nascent topics of expatriate classifications, structures, and costs. Next, international missionaries are compared to these topics. The conclusion proposes a modified business model for expatriate missionary assignments, offers implementation actions, and discusses implications for future research.

Literature Review

Expatriate Classifications

About three percent of the world’s population are considered international migrants (UNESCO, 2017). Totaling at 244 million people in 2015, international migrants are defined as people who are living for one year or longer in a country other than the one in which he or she was born (UNESCO, 2017).

Expatriates are a subcategory of migrants; these are individuals who move to another country and execute legal work abroad (Andresen, Bergdolt, Margenfeld & Dickmann, 2014). There are two major classifications of expatriates commonly discussed: assigned expatriate or self-initiated expatriates (SIE), although categories further defining expatriate assignments have been subject to debate (Nowak & Linder, 2015; Andresen et al., 2014; Cerdin & Selmer, 2014).

An assigned expatriate is commonly defined as an employee who is sent abroad by his/her company, while an SIE is defined as an individual who initiates his/her international work experience with little or no organizational sponsorship (Andresen et al., 2014). These authors offer a decision tree to determine the classification; three distinguishing criteria are needed for an individual to be classified as an SIE: (a) relocates from his/her dominant place of residence (migrant), (b) legally executes work abroad (expatriate), and (c) acts on first key binding activity (i.e., the individual takes the initiative to start working abroad) (Andresen et al., 2014). In contrast, Cerdin and Selmer (2014) define an SIE according to four criteria which must all be fulfilled at the same time: (a) self-initiated international relocation, (b) intentions of regular employment, (c) intentions of a temporary stay, and (d) skilled/professional qualifications. Literature has advanced a common semantic for expatriate classifications.

Expatriate Composition and Structure

Individual workers represent the largest segment (63%) of the estimated 50 million expatriates; however, the student segment (14% of total) has the highest growth rate, a 7% compounded annual growth over four years (Finaccord, 2014). During college, students are incurring debt that casts a burden on their financial security long after graduation. Friedman (2018) shows that 68% of college students graduate with substantial student loan debt, and the $1.5 trillion in student loan debt is now the second-highest consumer debt category. With this debt burden, students are attracted by the higher wages and international experiences that expatriate assignments offer. Meanwhile, these higher costs are also taxing organizations.

Expatriate assignments are typically viewed in three phases: before, during, and after the expatriate appointment. Before appointment, expatriates are engaged with planning, training, and preparing for the relocation and new tasks. During the appointment, expatriates perform the work outlined by the employer. Compensation is paid, support for employees is provided, and performance is evaluated. Lastly, after the assignment, employees are assisted in new roles with hopes of minimal career disruption (Doherty & Dickmann, 2012).

Expatriates can be used to launch an international office. Current headquarter employees relocate to a new locale with plans to increasingly transition operations to local talent. One study shows higher long-term growth is achieved when higher proportions of expatriates are present at the subsidiary founding, followed by a slow reduction in the percentage of expatriates over time (Riaz, Rowe, & Beamish, 2014). Structuring the number of expatriates and length of stay should be evaluated with benefits compared to offsetting costs.

Expatriate Costs and Financial Benefits

While literature is converging toward standard definitions and classifications for expatriates, the measurement and costing of expatriate assignments are disparate. “Sending expatriates on international assignments is a costly endeavor, and the benefits of assignments are often difficult to assess” (Nowak & Linder, 2015, p. 88). In one study, it was discovered that only 14% of respondents were able to determine a return on investment (ROI) (Johnson, 2005). This section examines the indicated financial valuation tool for expatriates, ROIs, its calculations, and its various components. Costs are considered first, then benefits.

Expatriate ROI is “a calculation in which the financial and non-financial costs to the firm or organization are compared with the financial and non-financial benefits of the international assignment, as appropriate to the assignment’s purpose” (McNulty & Tharenou, 2004, p. 73). To calculate ROI, the return (or benefit) of an investment is divided by the cost of the investment. The investment (or costs) of an expatriate assignment is often the easier component to quantify. Examples of costs are salary, relocation expenses, training, and replacement/turnover costs; examples of benefits are the internationalization of key managers to support a global strategy and increases in firmwide competitive advantage (McNulty & Cieri, 2013). Measuring benefits proves more challenging as the evaluator must define and be able to measure success in the assignment (Johnson, 2005).

Cost parameters are provided in many studies as ranges between local employees and expatriates, as well as typical length of stays. Doherty and Dickmann (2012) estimate that the average cost for an expatriate assignment is £462,212, (equivalent to $605,775 in 2012 or $612,270 in 2018), an amount significantly higher than a local employee hired for the same time period. In the sample, the length of the mean expatriate assignment is 28 months (Doherty & Dickmann). Johnson (2005) indicates an expected cost for an expatriate employee is at least three times the local employee’s annual salary, and the typical assignment length is three to five years. These studies implicitly represent assigned expatriate assignments (company initiative to send the employee), while SIE assignment research is sparse and could result in broader cost ranges.

Measuring expatriate benefits, however, is complex and likened to “unearthing the ‘holy grail’ of international mobility” (Doherty & Dickmann, 2012, p. 3436). McNulty and Cieri (2013) note that most companies lack sound practices for measuring success (or benefits) of an assignment abroad. Nowak and Linder (2015) question if cultural, strategic, and operational barriers render it too challenging to evaluate expatriate benefits and, thus, ROIs. While other alternatives have been suggested, such as intellectual capital valuation (Welch, Steen, & Tahvanainen, 2009), ROI is the prevalent measurement for expatriate assignments.

Measuring expatriate ROI distracts managers from focusing on what matters (McNulty & Cieri, 2013). Additional factors impact ROI valuations. Expatriates may be well-qualified in the designated job skills, but the adjustment to new surroundings and customs represents an additional challenge. Folsom, Gordon, Van Alstine, and Ramsey (2016) stress the necessity for sensitivity in regards to differences in style (competitive versus consensus-building), timing, procedure, linguistics, and culture. The inability to adjust to a new culture is given as the most common reason for failure (Cranston, 2018). These challenges reinforce the need for preparation and support throughout the expatriate assignment.

Discussion

Missionaries as Expatriates

In separately distinct literature, missionaries are defined as “those who, in response to God’s particular call on their life, often must give up traditional employment opportunities for the purpose of following God’s call to a foreign context” (Dixon, 2015). International missionaries act on their calling, relocate to a foreign country, and find sponsorship/employment through churches or ministries. A simple analogy is expatriates are to corporations, as missionaries are to churches/ministries. According to Andresen et al. (2014), an SIE takes the initiative to work abroad, relocates, and performs work abroad. This article assumes that missionaries seek out work abroad in response to God’s calling and apply to a mission’s board that manages the logistics and the objectives of the relocation; thus, missionaries will be evaluated as SIEs.

Missionary Composition and Structure

Approximately 400,000 Christian missionaries target a 2.1 billion unevangelized population, 29% of the world’s population (Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, 2015). Missionaries are typically supported by at least one of the 4.3 million church congregations and/or the 5,100 Christian ministry agencies.

The supporting churches or ministries are typically responsible for helping the missionary throughout the assignment (hereafter referred to as “missionary care”). Missionary care for missionaries is analogous to relocation agents and corporate human representatives for corporate expatriates. Similar to expatriate assignments, missionary assignments can be viewed in the before (preparing to relocate), during (performing work in a new location), and after (readjusting back home) phases. In contrast to corporate expatriate assistance, missionary care includes encouragement and development of the whole family, and the timeframe is extended through retirement (O’Donnell, 1992). Not only do missionary compensation packages designate retirement saving plans, missionaries frequently choose to continue their ministry well past retirement age. Missionary care is instrumental in the preparation and longevity of missionary assignments.

While expatriates take orders from their employers, missionaries are called by God to join the Great Commission. Jesus commands, “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matt. 28:19, NIV). Speaking to His disciples, Jesus says, “You did not choose me, but I chose you and appointed you so that you might go and bear fruit–fruit that will last–and so that whatever you ask in my name the Father will give you” (John 15:16, NIV).

Missionary Costs and Benefits

With expatriate ROI as a common valuation, missionary costs and benefits are discussed. While companies pay for expatriate costs, some missionaries raise funds to cover the majority of their expenses. Funds are primarily secured through donations from churches, organizations, or individuals. Missionary costs include, but are not limited to, ministry programs and supplies, living expenses, family care (such as medical and children’s education), and retirement savings. Overall, financial annual giving to Christian causes is reported at $700 billion (Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, 2015); in contrast, Americans spend that amount annually on Christmas gifts (Statista, 2017). Regardless of who provides the funding (i.e., mission boards, individual churches, individual donors, or a combination of these and others), the total cost of Christian outreach averages $330,000 for every newly baptized person (Barrett & Johnson, 2001).

Jesus told His disciples to take no heed as to what it costs. In Matthew 10:8, Jesus reminds them that they received the Good News without paying, and thus, they must to freely give to others. Jesus says, “Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothes?” (Matt. 6:25, NIV).

Uncalculatable costs, such as lack of safety, are not included or even acknowledged in any valuation instruments. A foreign missionary is the fifth most dangerous of all Christian vocations (Barrett & Johnson, 2001), and Christians are named the most persecuted group in the world (Chiaramonte, 2017). “Make no mistake about it: obeying the Lord’s command to disciple the nations has and always will be costly. It is risky business” (O’Donnell, 1992, p. 1).

Organizational benefits for all expatriation (corporate and ministry) are gained through knowledge transfer and heightened cultural awareness. Corporate administrators may place value on the knowledge transfer or gains from competitive advantages expected from an expatriate assignment. In contrast, church administrators may view service attendance and/or conversion of people’s souls as the “benefit.” Thus, an expatriate ROI fails to adequately assess and incorporate the benefits of the spiritual nature and intangible benefits of a missionary assignment.

Intangible benefits accumulate as missionaries “raise the consciousness of others that, responding to Jesus’s message, they may transcend culturally created division and come face to face with God.” (Burridge, 2007, p. 5). “Christian missionaries are . . . men and women of faith, hope, and a dogged perseverance. Their reward lies in the ways in which their lives may be judged in heaven as in the imitation of Christ” (p. 9), rather than any quantifiable measure on earth.

Despite the lack of effective earthly valuations, the Bible states that every time a soul is saved, the angels in heaven rejoice, epitomizing immeasurable wealth. Luke 15:7 tells us that “there will be more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who do not need to repent” (NIV).

Tangible and intangible factors influence ROI measurements. Factors affecting ROIs include but are not limited to cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adaptation, job performance, assignment length, expatriation experience, and others. Shi and Franklin (2014) find that expatriates who travel with partners or family members experience more positive cross-cultural adjustments and better job performance. Job performance for missionary expatriates is significantly improved since 67% of evangelical missionaries are married couples (Piper, 2016). Furthermore, if the benefit is immeasurable joy and costs are minimal (finite) based on self-funding, then ROI calculations equate to infinity divided by a number that results in infinity; thus, ROI valuations are phenomenal.

ROIs are shown to be ineffective, yet indeterminately applied, measures of expatriate assignments. A factor that further widens the valuations gap between corporate and missionary expatriates deals with goals. Individuals may focus on career-oriented goals, such as promotions, while corporate goals are businessneed driven (Doherty & Dickmann, 2012). Alternatively, missionaries tend to choose a church or ministry organization that aligns with their personal beliefs, goals, and mission. “Christian missionaries are unusual in that while most classes of people can be presumed to be preoccupied with their own interests, missionaries . . . give themselves over to the critique and transformation of other peoples’ business” (Burridge, 2007, p. 5). Missionaries

see people as God does and engage in the activity of reaching them. The church on mission is the church as God intended, loving our neighbors as ourselves, and proclaiming the good news of redemption found in Jesus. (Farmer, Page, & Vaters, 2017, p. 3)

Goal orientation and motivation significantly impact valuations and successes of expatriate work.

While an international missionary assignment could be classified into the self-initiated expatriate (SIE) definition, the Scriptures define missionary work as revered efforts when God’s people follow His commandments. Jesus said, “I have made you a light for the Gentiles, that you may bring salvation to the ends of the earth” (Acts 13:47, NIV). Thus, ROI calculations are exponentially difficult for missionary assignments due to the immeasurable and uncalculatable costs (self-funding, family members, extended stays, safety) and intangible benefits (heavenly rewards). An alternative framework is suggested next.

Ministry Valuation Playbook (MVP)

While ROIs are ineffectual when applied to missionary assignments, ministry leaders can leverage alternate valuations and business strategies. Christian organizations have unique and distinct values and beliefs; however, they could “stand to learn a few lessons from their shrewd worldly neighbors about running the business” (O’Donnell, 1992, p. 221).

The balanced scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1992) offers a framework with strategy at the center surrounded by four perspectives: customer, learning, process, and financial. Strategy is represented by the company’s goals based on its mission and vision. To break down the strategy into actionable steps, the balanced scorecard offers four perspectives. Each perspective poses a question to help managers see the business from a unique point of view. First, the customer perspective determines if the company is meeting its stakeholders’ needs. Secondly, the learning perspective questions how the organization can continue to improve amid changes (new regulations, economic changes, etc.). The process perspective asks how the company can increase efficiency and excel in its internal processes. Lastly, the financial perspective ponders how to succeed and achieve financial stability. Combined, the four views ensure a balanced approach for moving towards organizational goals.

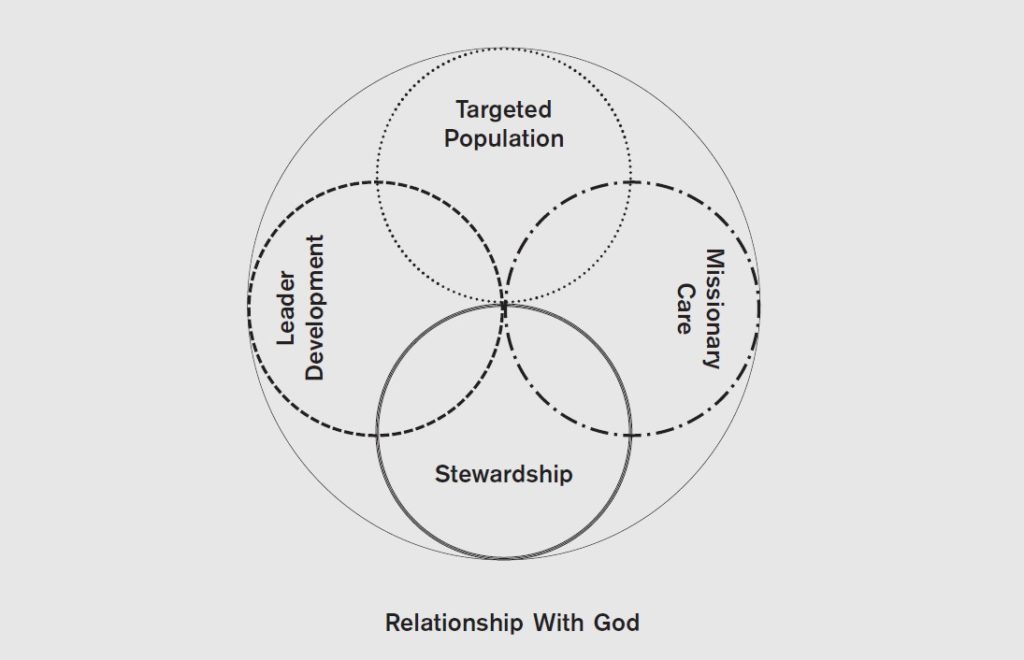

This author proposes an original construct based on the balanced scorecard framework, modified to become the Ministry Valuation Playbook (MVP), a valuation tool to assess missionary endeavors more succinctly. The MVP supports the relationship with God as the core strategy and incorporates the four perspectives: targeted population (customer), leader development (learning), missionary care (process), and stewardship (financial). Figure 1 indicates the relationship between the core strategy and the four perspectives. Notice the overlap of the perspectives in the diagram that show perspectives have mutual concerns, shared responsibilities, successes, costs, and benefits.

Figure 1. Ministry Valuation Playbook (MVP)

The MVP is intended for use by churches and ministries to value missionary assignments. A brief description is provided for the MVP core strategy and the four perspectives with their corresponding questions.

Core Strategy: Relationship with God

A ministry’s core purpose is to make disciples (Matt. 28:18; Mark 16:15). Before all else, the missionaries and aligned missionary care partners must have a healthy relationship with God. The greatest commandment is to love God with all of your heart, soul, and mind (Matt. 22:37). Primary relationship indicators are obedience, perseverance, trust, perspective, and testing (O’Donnell, 1992). Evaluation of the missionary assignment begins here.

Perspective 1: Targeted Population

How do non-believers view the missionary? Christians, especially missionaries and other religious leaders, are under constant scrutiny and investigation by non-Christians. The Bible instructs us to set an example and share our faith and hope in Jesus. “In the same way, let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven” (Matt. 5:16, NIV). Moreover, Romans 10:14–15 asks how one cannot share the good news with unbelievers:

How, then, can they call on the one they have not believed in? And how can they believe in the one of whom they have not heard? And how can they hear without someone preaching to them? And how can anyone preach unless they are sent? As it is written: “How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!” (NIV)

Metrics for the targeted population perspective can include the number of people reached, number of conversions/baptisms, planned versus actual attendance and participation in ministry programs, and feedback ratings from foreign church partners or missionary care partners. All performance metrics should be gauged periodically (such as quarterly) to celebrate success or to consider action plans if expectations are not met.

Perspective 2: Leader Development

How do missionaries develop in their role, as well as teach the next generation of leaders? This perspective tracks growth in one’s faith, progression in evangelism skills, and frequency of knowledge transfer. Scripture encourages seeking counsel (Prov. 15:22), leveraging God’s Word (2 Tim. 3:16), and sharing with others (2 Tim. 2:2). “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness” (2 Tim. 3:16, NIV). As missionaries and care partners learn and share, they are in God’s presence: “For where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them” (Matt. 18:20, NIV).

Equipping and developing leaders is vital for any organization. Ministries must invest in substantial planning to “strategically raise up and direct resources so as to put greater closure on the Great Commission” (O’Donnell, 1992, p. 289). Metrics for the learning development perspective could include hours reading the Bible per month, number of completed online training classes, number of leader development sessions held by the sponsoring ministry, and number of knowledge transfer meetings. Again, these performance indicators should be measured and documented at set regular intervals.

Perspective 3: Missionary Care

This process-based perspective focuses on the efficiency of internal processes of the sponsoring church or ministry. The organization must balance resources between achieving the mission and caring for staff. Scripture emphasizes the importance of community building and loving one another. Ephesians 4:16 describes how parts of a body help each other grow: “From him, the whole body, joined and held together by every supporting ligament, grows and builds itself up in love, as each part does its work” (NIV).

Investments in people are the best investments. Study results show that mission-sending organizations with high retention rates retain 78% of their people with an average service length of 22 years, compared to 38% retention and 10year service average in the lower retention group (Van Meter, 2003). With no surprise, the high retention group employs great rigor in selection criteria, provides an extended orientation (six weeks versus three weeks by the lower retention group), and offers more personal care services compared to the lower retention group. Investments in people development assists in accomplishing organizational goals (Olenski, 2015). Metrics for the missionary care perspective could include the number of services offered, percent of funding benchmarked to comparable organizations, and feedback ratings from missionaries based on services they received.

Perspective 4: Stewardship

Do missionaries and care partners act as good stewards of the organization’s resources? Stewardship embodies the responsible planning and management of finances, materials, and assets. Organizations must be held accountable for the allocation and distributions of donations and grants and invest them wisely.

Missionaries and ministries must work together to identify generous individuals and organizations who are willing to give donations and grants to fund evangelical programs and activities. Stewardship metrics are the most established. Number of donors, total donation dollars, grants dollars, and timing are basic metrics to employ.

In summary, the MVP framework begins with a relationship with God and offers four perspectives (targeted population, leader development, missionary care, stewardship) to boost analysis and broaden reflection on missionary assignments.

MVP Implementation Actions

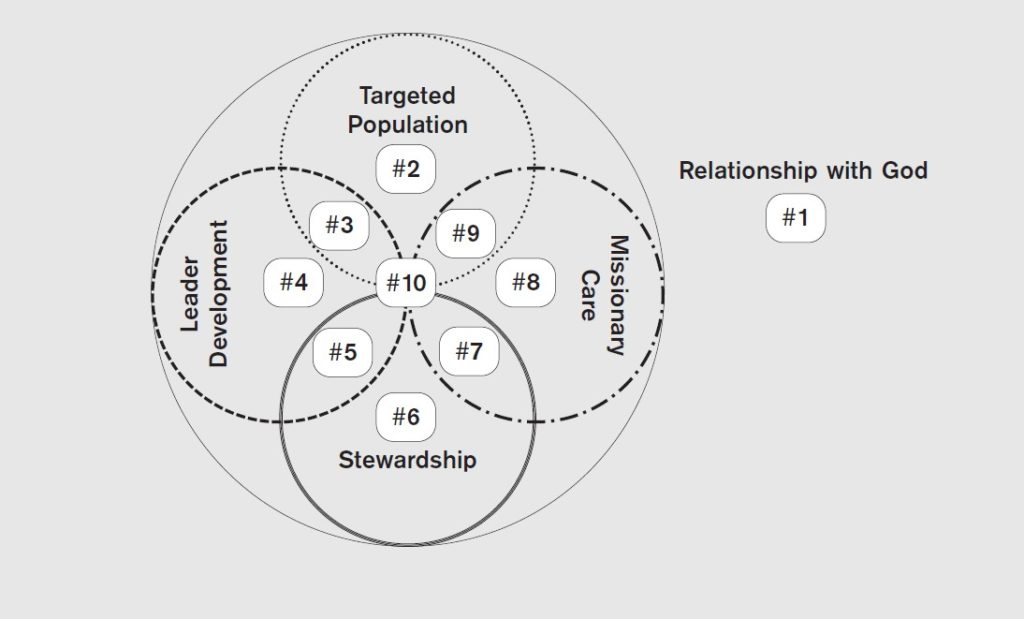

Ten implementation actions are suggested in establishing the MVP framework. Figure 2 shows how these actions, when added to Figure 1, further illustrate the collaborations between the various perspectives and reinforce the dominant core strategy guiding all decision-making.

Figure 2. Suggested Actions for the MVP model

The ten suggested actions to employ the MVP are:

- Clearly state the mission, define measurable performance goals, and esti- mate required commitments. Cascade this information throughout the orga- nization, including supported missionaries.

- Solicit information from targeted ministry areas regarding spiritual needs, as well as other pertinent regional data. Request this information with grace and love.

- Design introductory online personnel courses regarding cultural, geographi- cal, economic, demographic, and political factors about targeted area min- istries to better prepare missionaries for cross-cultural adaptations.

- Seek wisdom from former or current missionaries, and participate in short global missionary trips for preliminary values assimilation and cultural per- ceptions and awareness.

- Sponsor several missionaries who live and work in different countries. Invest in many ventures to accept diversified risks and ultimately reap benefits.

- Invest contributions and monitor growth monthly. Create a simple tracking system to ensure contributions received from donors exceed the grants paid out for missionary care.

- Collect and disseminate detailed updates to contributory institutions and participating community members. In addition to standard financials and annual reports, personalized notes or phone calls should report back on donation specifications and wishes.

- Personalize the ministry by providing missionaries facts and ideas pertinent to their area or demographic. Institute/moderate chat rooms to facilitate per- sonal involvement and communications.

- Equip missionaries with technological resources for targeted communities. Technological advances can allow Christians to evangelize everywhere on earth.

- Learn. Adapt. Repeat. Refine protocols based on findings to improve out- reach efforts further. A ministry will flourish with knowledge and under- standing, but honest reflection and flexibility keep it healthy.

Each perspective has its expectations and obligations, yet interacts with others to overcome the overwhelming responsibilities and separations sometimes experienced in missionary endeavors. The last action ties together all the efforts of the four perspectives under the core strategy, empowering all constituents to understand the broader vision of the core strategy better and improve efforts to achieve the goals of the organization, hopefully more effectively.

Conclusion

Amid spiritual warfare and struggling financials, Christian ministries continue to deliver on their missions and share the Good News with nonbelievers. Despite unfounded predictions of the collapse of religion, Christianity is here to stay.

Following sound business practices and Biblical principles, the Ministry Valuation Playbook framework provides a tool for churches and ministries sending missionaries to increase accountability, improve communications and transparency, and enhance community building. Ten implementation actions are offered to inculcate MVP and reinforce the broader vision of the organization.

Future studies can expand to other facets of ministry valuation. More qualitative evaluations must be applied to missionary work. Instilling measurement of intangibles, such as the mounting importance of cultural learning in an increasingly globalized world, is needed. Chief financial officers (CFOs) of ministry organizations are positioned to guide the international implementation of such programs. Financial professionals can assess areas of concern and construct proven financial procedures to maximize impact and reduce costs to individual participants. While financial benefits may still be challenging to determine, returns on investments will be exciting to witness. Just call your favorite missionary and ask!

References

Andresen, M., Bergdolt, F., Margenfeld, J., & Dickmann, M. (2014). Addressing international mobility confusion–developing definitions and differentiations for self-initiated and assigned expatriates as well as migrants. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(16), 2295–2318. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.877058

Barrett, D., & Johnson, T. (2001). World Christian trends, AD 30–AD 2200. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library.

Burridge, K. (2007). In the way: A study of Christian missionary endeavours. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Cerdin, J., & Selmer, J. (2014). Who is a self-initiated expatriate? Towards conceptual clarity of a common notion. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(9), 1281–1301. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.863793

Chiaramonte, P. (2017). Christians are the most persecuted group in the world for the second year. Fox News. Retrieved from http://www.foxnews.com/world/2017/01/06/christians-most-persecuted-group-in-world-for-second-year-study.html

Cranston, S. (2018). Calculating the migration industries: Knowing the successful expatriate in the global mobility industry. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(4), 626–643. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1315517

Dixon, A. (2015). Understanding the cost of missionary support. Mission Network News. Retrieved from https://www.mnnonline.org/news/understanding-the-cost-of-missionary-support/

Doherty, N., & Dickmann, M. (2012). Measuring the return on investment in international assignments: An action research approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(16), 3434–3454. doi:10.1080/09585192.2011.637062

Farmer, J., Page, F., & Vaters, K. (2017). Small church, excellent ministry: A guidebook for pastors. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

Finaccord. (2014). Global expatriates: Size, segmentation and forecast for the worldwide market report. Finaccord. Retrieved from http://finaccord.com/documents/rp_2013/report_prospectus_global_expatriates_size_segmentation_forecasts_worldwide_market.pdf

Folsom, R., Gordon, M., Van Alstine, M., & Ramsey, M. (2016). International business transactions in a nutshell (10th ed.). St. Paul, MN: West Academic Publishing.

Friedman, Z. (2018). Student loan debt statistics in 2018: A $1.5 trillion crisis. Forbes Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/zackfriedman/2018/06/13/student-loan-debt-statistics-2018/#3a5ef8f7310f

Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. (2015). Christianity 2015: Religious diversity and personal contact. International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 39(1), 28–29.

Johnson, L. (2005). Measuring international assignment return on investment.

Compensation & Benefits Review, 37(2), 50–54. doi:10.1177/0886368704274343

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 71–79.

McNulty, Y., & Cieri, H. (2013). Measuring expatriate return on investment with an evaluation framework. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 32(6), 18–26. doi:10.1002/joe.21511

McNulty, Y., & Tharenou, P. (2004). Expatriate return on investment: A definition and antecedents. International Studies of Management & Organization, 34(3), 68–95.

Millar, J., & Salt, J. (2008). Portfolios of mobility: The movement of expertise in transnational corporations in two sectors–aerospace and extractive industries. Global Networks, 8(1), 25–50. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2008.00184.x

Nowak, C., & Linder, C. (2015). Do you know how much your expatriate is? An activitybased cost analysis of expatriation. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 16069–16069. doi:10.5465/ambpp.2015.16069abstract

O’Donnell, K. (1992). Missionary care: Counting the cost for world evangelization. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library.

Olenski, S. (2015). 8 key tactics for developing employees. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/steveolenski/2015/07/20/8-key-tactics-for-developing-employees/#318f34226373

Piper, J. (2016). Why are women more eager missionaries? Desiring God.com. Retrieved from https://www.desiringgod.org/interviews/why-are-women-more-eager-missionaries

Riaz, S., Rowe, W., & Beamish, P. (2014). Expatriate-deployment levels and subsidiary growth: A temporal analysis. Journal of World Business, 49(1), 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2013.04.001

Shi, X., & Franklin, P. (2014). Business expatriates’ cross‐cultural adaptation and their job performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 52, 193–214. doi:10.1111/1744-7941.12003

Statista. (2017). Holiday retail sales in the United States from 2000 to 2017 (in billion U.S. dollars). Statista. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/243439/holiday-retail-sales-in-the-united-states/

UNESCO. (2017). Migration, free movement and regional integration. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.

Van Meter, J. (2003). US report of findings on missionary retention. World Evangelicals. Retrieved from http://www.worldevangelicals.org/resources/rfiles/res3_95_link_1292358708.pdf

Welch, D., Steen, A., & Tahvanainen, M. (2009). All pain, little gain? Reframing the value of international assignments. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(6), 1327–1343. doi:10.1080/09585190902909855